Narrow (thin) markets in commodity row crops

The market structure of row crops

Monopolies are bad in general, other than for the individual or entity who or which is the monopoly.

State owned monopolies are the worst, as they don’t even have a profit motive. As a small kid in India, we didn’t have a phone to begin with and we didn’t get a phone till I was about 10-12 years old.

My parents had no desire to live off the grid, but there was just one seller for telephone services. It was the Indian state. It took 13 years from when my parents registered to get a land-line phone, to actually getting a land-line phone. (This was pre mobile phone era, and pre opening up of the Indian economy in 1991).

The opposite of a monopoly is a monopsony. In a monopsony, there are many sellers, and only one buyer. For example, in the case of space equipment, where there were a few sellers, but there used to be only one buyer - NASA.

In a competitive market, you have a large number of sellers and a large number of buyers, and it is best suited for improved customer experience, and innovation.

Thin markets

What happens when you have a small number of buyers and a small number of sellers? How does this market perform compared to a monopoly, monopsony, or a competitive market. These types of markets are called narrow (or thin) markets.

For example, there are two big aircraft companies (Boeing & Airbus) and a few hundred airlines. You typically see this in infrastructure plays, as there are few sellers who can actually execute a project of certain kinds (for example, building airports).

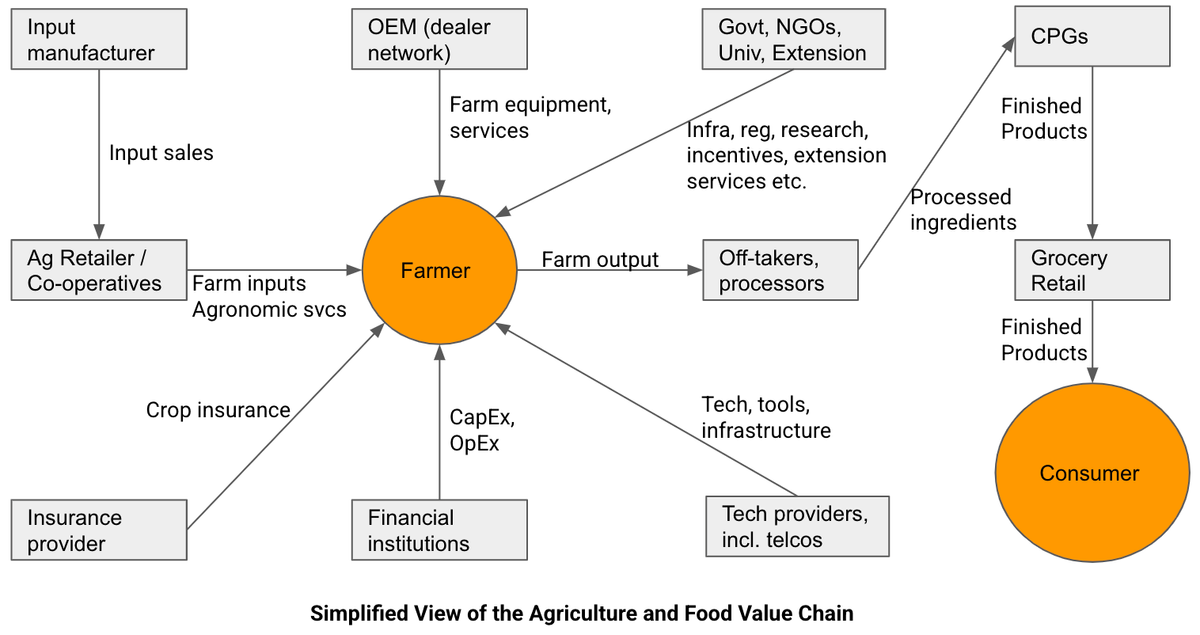

You see a similar dynamic play out in commodity row crops in North America. It is common to talk about how there are only a few seed companies, or only a few equipment companies, or only a few offtakers (or processors).

U.S. agricultural production is becoming more concentrated at the farm level. For example, in 1970, nearly 650,000 dairy farms operated in the U.S.; today roughly 40,000 remain.

The number of commodity row crop operations in the US is limited to a few thousand operations. If you look at all farms, 11% of the farms account for 80% of the production value.

US commodity row crop markets are characterized by a few sellers (farmers) and few buyers (off takers) on the output side, and a few sellers (input, OEMs, etc.) and a few buyers (farmers).

The US commodity row crop markets fit the definition of narrow (or thin) markets.

Narrow markets create challenges around transparency and pricing fairness during the product procurement stage. Low transaction volumes and low liquidity in narrow markets reduces visibility on price and volume data.

This makes incorporation about how new data about a commodity is being included in the price quite challenging, leading to price volatility. It is often difficult to figure out what a farmer really pays and how much does a seed company charge for a bag of seed, due to all the different rebates, discounts, and specials. The narrow markets make obfuscation easier than a competitive market. Small producers are at a natural disadvantage in a narrow market. Large producers can spread their fixed costs over a larger area.

Markets become narrower (or thinner) as consumer and animal feed demand becomes more differentiated due to heightened product heterogeneity. Beyond conventional preferences of taste, appearance, convenience, and price, many Americans now desire food attributes related to health, ESG concerns, treatment of animals, fair practices, different attributes for animal feed etc.

The evolved preferences do present farmers with opportunities to differentiate their products and develop market niches, but they make the market narrower in each attribute niche.

Are there oligopolies in agriculture?

“An oligopoly is a market dominated by a few suppliers. Although supply and demand influences all markets, prices and output by an oligopoly are also based on strategic decisions: the expected response of other members of the oligopoly to changes in price and output by any 1 member. A high barrier to entry limits the number of suppliers that can compete in the market, so the oligopolistic firms have considerable influence over the market price of their product.”

Here are some statistics based on a report titled “Food and Power: Addressing Monopolization in America’s Food System” published by the Open Markets Institute (2021)

- Four corporations, Cargill, Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge, and Louis Dreyfus, control close to 90% of the global grain trading business. Vertical integration is common, with farmers relying on the same corporation to purchase seeds and inputs, process raw materials, and manufacture products like animal feed and corn syrup.

- 2 corporations manufacture nearly 50% of all tractors & other essential farm machinery in the US.

- Similar trends are seen in seed companies for corn & soybean, and herbicides & pesticides.

Source: The soberting details behind the latest seed monopoly chart (Civil Eats) (2019)

What is driving the concentration in the industry? Is it technology, distribution, business model, or some other factor?

In the case of internet businesses, higher volume and scale drove down marginal costs to zero. This allowed a few companies to grow, and become giant behemoths.

In the case of agriculture, the incumbents have not changed much in the last few decades, other than resetting the chess board a bit.

Many ag and agtech companies have talked about a data flywheel in agriculture.

“The data flywheel is the idea that more users get you more data which lets you build better algorithms and ultimately a better product to get more users.”

We have not seen a strong data flywheel effect in agriculture as it is very difficult to get leverage without distribution. Access to distribution is controlled by incumbents and due to the existing physical infrastructure and relationships.

Even in a technology business in agriculture, the marginal costs don’t go to zero or decline at a fast enough rate. It makes the entry of new players difficult. Given the not-so-large number of commodity row crop farmers in North America, there might not be enough business for a new player to reduce the marginal cost of a new customer to a level which makes unit economics sustainable.

Agtech Implications

What are the implications for agtech companies and agtech in general, if they operate in thin markets like the commodity row crop market in the US?

If you are selling a low selling price product to commodity row crop farmers, then you are in for a tough ride. You have a limited number of customers you can sell to, and the average revenue per customer is low, while the sales and marketing costs are still high. This is not a great combination, especially if you are a startup.

Given farming diversity, any particular cut of heterogeneity makes the markets even thinner.

Agtech is a graveyard of startups, especially the ones who try to sell directly to farmers in North America. Yes, it is absolutely true, your solution has to create value for the farmer. But even if it does, unless the average revenue per customer is high, it becomes challenging to sell in a thin market. We have many such examples, even when the product being sold was by a large incumbent. For example,

- Corteva and Granular have reached a conclusion. SaaS based products with a few hundred dollars of revenue per farming operation are very difficult to sell, and to create a real business out of it. Corteva has decided to sunset certain products like Granular Insights etc. It is also very difficult to build a technology product, and thin markets don’t help. Input companies are concluding digital is a means to an end to help sell more & better inputs.

- Farmer’s Edge has famously crashed and burned, even though it had a host of other internal issues. (You should read my friend Shane Thomas’ analysis on it.)

- Bayer’s Climate FieldView started off with a $ 999 per year price tag a few years ago. The price was still too large to create significant friction in adoption. Bayer dropped the price to $ 99 per year. Farmers also struggle with $ per acre pricing, and prefer fixed pricing. Bayer still offers a $ 1 / acre prescription plan, but the expensive seed and fertility prescription plans of $ 3 and $ 4 per acre have disappeared. Most input companies treat their digital offerings as a sales enablement and customer engagement tool, to be paired with input and advisory services.

Technology products (involving hardware and software) become cheaper while the quality improves.

Thin markets are not ideal for startups selling technology only or digital only products. They don’t have access to distribution, small markets will make it challenging to build a large business for startups due to high S&M costs, but lower ARPU (average revenue per user).

So what should you do if you are a startup with a digital or technical product idea for commodity row crop farmers in the US?

- If you think your average selling price is going to be lower compared to other inputs, find market traction and then try to get acquired by a large incumbent.

- Try to go B2B instead of selling directly to farmers.

- Try to get included as an add-on-service or product pushed by an incumbent.

- For incumbents, try to find smaller players with reasonable traction, and partner with them to add their capabilities in your bundle.

Thin markets are not ideal for startups selling technology only or digital only products. They don’t have access to distribution, small markets will make it challenging to build a large business for startups due to high S&M costs, but lower ARPU (average revenue per user).

New business models and new technologies

The thin market is a constraint for distribution, which makes leverage lopsided and favors the existing actors. For new entrants, you need to have a much better solution, but it also has to be cheaper. In other industries, a large volume of customers for a new entrant can help them drive down the cost curve. But due to a thin market, there are a limited number of farmer customers to drive down costs.

Due to this innovation returns to the status quo for incumbents, as old players are incentivized to keep market share.

How can these thin markets be navigated? Can the market conditions be changed, using different business models, and the age old change agent - technology?

For example, it might make more sense to start with a B2B opportunity, as it makes starting off a bit easier. But this might be a marginal change (definitely in the short to medium term), as you might only be able to sell to existing players.

Can technology and digital enable new business and distribution models? Digital can enable the removal of the middle person.

Can a large part of the inputs business convert to a D2C (or direct to farmer) business? Can you simplify the supply chain with fulfillment centers, which removes the middle man (or woman) and transforms a significant portion of your value chain?

Is the distribution problem really an agriculture problem, or is it a logistics, infrastructure, and technology problem? For example, Pin Duo Duo consolidated buying & selling, and provided the logistics infrastructure.

Is it possible for farmers to buy most of their inputs online, and have a recommendation and analysis layer which reduces the need for the middle man?

At least in the US, the logistics infrastructure does exist.

For example, Amazon now has fulfillment centers within one hour of 77% of Americans, UBS estimates. That’s a lot, but it still trails well behind Walmart, whose nearly 5,000 stores across the US put it within an hour of 99% of the US population by UBS’ tally.

Image: Source

Can a partnership between input companies and Walmart provide the logistics infrastructure (given 99% of the US population lives within an hour of Walmart)?

Why would Walmart do it? This could be an interesting expansion of business for Walmart, which is seasonal in nature. They already have a supply chain infrastructure in place.

It could potentially bring some additional customers. (albeit a small number, given the small number of commodity crop growers). For example, Kohl’s has benefited from Amazon returns, and they signed up 2 million new subscribers in 2020.

Farmers have typically relied on agronomists, and input salespeople to make decisions on input buying. Most of this experience has been an in-person experience. COVID taught us we can do many aspects of our jobs remotely. For example, Warby Parker made ordering a pair of prescription glasses online easier. Stitch Fix has automated something so personal like fashion choices.

Even something as critical as going to the doctor, has worked out reasonably well in a remote setting, for certain types of issues.

For example, in a study of 2,393 participants from an academic integration multispecialty healthcare institution, 2080 (86.9%) cases displayed diagnostic concordance between virtual and in-person visits. (“Medical specialties also displayed a wide range of concordance levels. Diagnostic concordance was 77.3 percent for otorhinolaryngology (study of diseases of the ear, nose, and throat.) and 96 percent for psychiatry.”)

As the medical diagnostic example shows above, there are certain situations where a remote session works as well as an in-person session, while certain issues (ENT) which might require special equipment or lighting do not work as well.

Can we think of innovation where seed and chemical companies provide agronomic products, and expertise, OEMs provide execution, a large retailer like Walmart provides distribution, and a sophisticated technology provider provides the technology backbone for it?

To get past the unique challenges posed by thin markets, will require new business models, different partnerships and alliances, and new technology and user experiences.