More shots on goal

Experimentation is key to innovation

More shots on goal

I.

Innovation is never a straight line, often it’s littered with near misses, pivots, and long nights considering what to try next. It’s often difficult, when working to do something truly revolutionary, what the next step should be or if you’re at all close to what you’re attempting to do.

Thomas Edison was one of the most successful innovators in American history. He was the “Wizard of Menlo Park,” a larger-than-life hero who seemed almost magical for the way he snatched ideas from thin air.

But the man also stumbled, sometimes tremendously. In response to a question about his missteps, Edison once said, “I have not failed 10,000 times—I’ve successfully found 10,000 ways that will not work.”

Thomas Edison demonstrating his tinfoil phonograph, photograph by Mathew Brady, 1878. Courtesy of the Edison National Historical Site, West Orange, N.J.

Several inventions over the history of mankind have stories about the invention, but seldom get into the several at-bats it took to make the final breakthrough. Whether it’s getting more no’s than yes’s in finding the right investor to get your idea funded, as was the case with Howard Shultz and the 217 out of 242 investors that turned him down when he pitched Starbucks, or the several years of attempts it took the Wright brothers to finally achieve flight, it often takes many attempts before finally getting it right.

It’s clear across many stories of disruptive innovations, that taking more shots on goal is the way to make a truly impactful breakthrough.

II.

Concentration in any industry does not create ideal conditions for innovation. A limited set of players can stifle innovation, move too slowly, or may be too risk averse.

More importantly, individuals within companies have an uphill battle when trying to launch an innovation initiative with most failing due to the numerous obstacles that exist within typical corporations, from company politics to extensive decision making hierarchies. This not only hinders agility within large companies, but also makes it almost impossible to launch truly disruptive innovations within a large enterprise.

The same is true when working within the SMB space however, as smaller companies have smaller budgets and in areas like agriculture, are more spread out and lead to a much more costly sales cycle. It’s the case that businesses of any size have a hard time adopting and implementing innovations, which makes it difficult to then build / fund / deploy truly new solutions inside an enterprise or alongside a small to medium sized business.

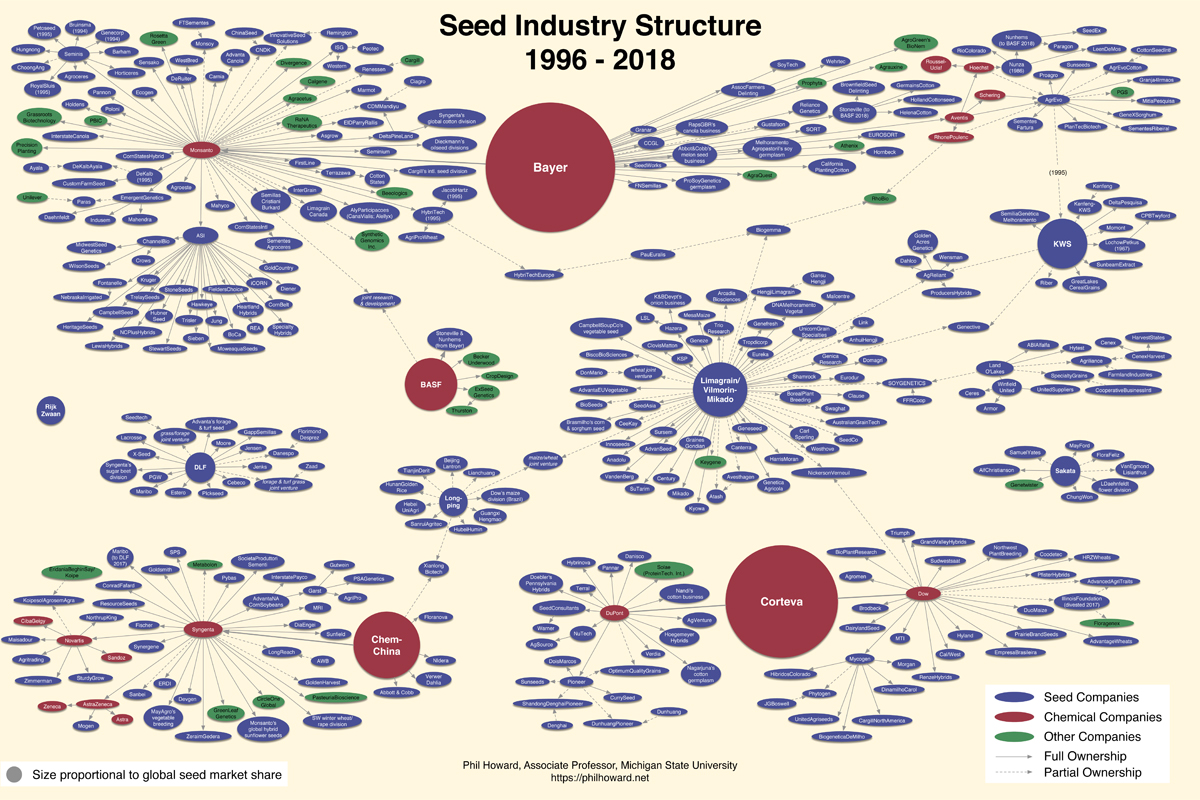

Related specifically to the agriculture industry though, as discussed in edition 117, this industry in particular is concentrated in many different sectors.

- Four corporations, Cargill, Archer-Daniels Midland, Bunge, and Louis Dreyfus, control close to 90% of the global grain trading business. Vertical integration is common, with farmers relying on the same corporation to purchase seeds and inputs, process raw materials, and manufacture products like animal feed and corn syrup.

- 2 corporations manufacture nearly 50% of all tractors & other essential farm machinery in the US.

- Similar trends are seen in seed companies for corn & soybean, and herbicides & pesticides.

Source: The sobering details behind the latest seed monopoly chart (Civil Eats) (2019)

III.

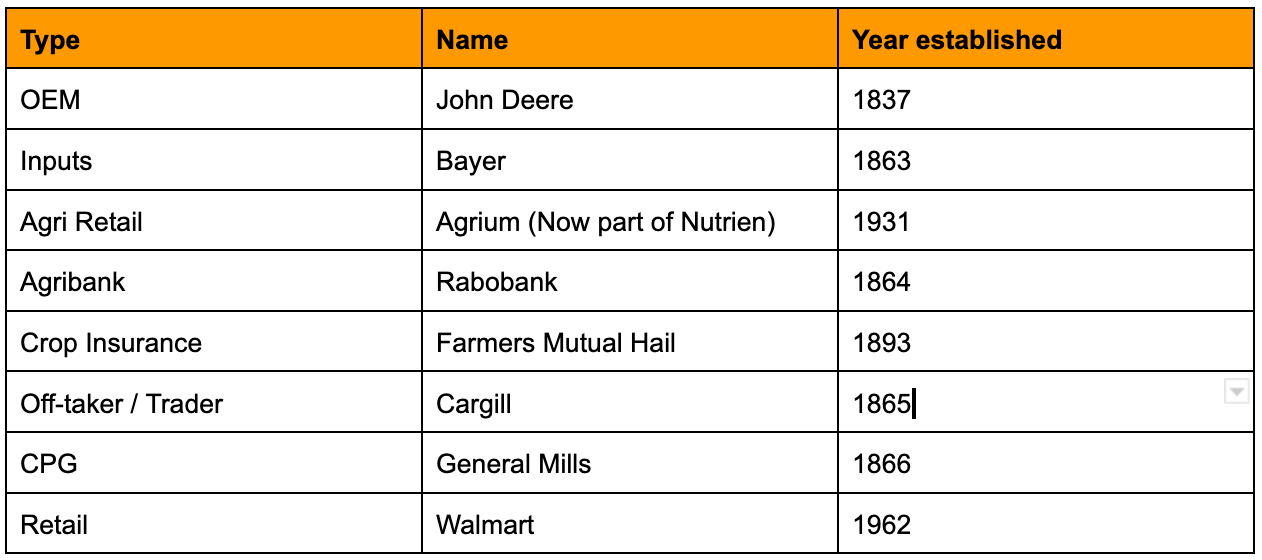

Agriculture is characterized by a concentrated structure in different parts of the food and agriculture value chain. Surprisingly, the large players today who dominate their sector have been around for a long time.

Edition 117 talked about narrow (thin) markets for commodity row crops in North America. To recap,

“US commodity row crop markets are characterized by a few sellers (farmers) and few buyers (off takers) on the output side, and a few sellers (input, OEMs, etc.) and a few buyers (farmers).

The US commodity row crop markets fit the definition of narrow (or thin) markets.”

Edition 117 talked about the challenges startups face in think markets and offered some suggestions for startups with digital or technical products for commodity row crop farmers in the US.

“Thin markets are not ideal for startups selling technology only or digital only products. They don’t have access to distribution, small markets will make it challenging to build a large business for startups due to high S&M costs, but lower ARPU (average revenue per user).

So what should you do if you are a startup with a digital or technical product idea for commodity row crop farmers in the US?

- If you think your average selling price is going to be lower compared to other inputs, find market traction and then try to get acquired by a large incumbent.

- Try to go B2B instead of selling directly to farmers.

- Try to get included as an add-on-service or product pushed by an incumbent.

- For incumbents, try to find smaller players with reasonable traction, and partner with them to add their capabilities in your bundle.”

Given the physical nature of agriculture, access to distribution is very important to scale your innovation.

“Agtech is a graveyard of startups, especially the ones who try to sell directly to farmers in North America. Yes, it is absolutely true, your solution has to create value for the farmer. But even if it does, unless the average revenue per customer is high, it becomes challenging to sell in a thin market.”

The key takeaway from the message in the thin markets writeup is not that everyone should go work for or collaborate with the big industry players only. It could be depressing if you are planning to do a startup in AgTech.

Working with the SMB space, as discussed above, can be equally as challenging. If your product or service is popular within a particular commodity or region, you have to be able to scale geographically as well as across several kinds of commodities with the high likelihood of limited growth potential per ag customer assuming you can fully scale at each farm over time which can also be difficult. Add on top of that the uncertainty around farming year over year, and it can make for a difficult sales cycle with a turbulent long term relationship with ag customers in addition to added complexity as you scale across geographies and commodities.

IV.

But innovation does not come from only working with the large behemoths, or SMBs. The primary driver of innovation when it comes to breakthrough innovations is not so much size, as the existence of genuine competition. Competition is more prevalent when you have a large number of players trying to go after similar problems. It’s not the targeted focus, sales strategy, or innovative go to market then, but rather how many companies are working in the same space as you to make meaningful breakthroughs with clients of any size.

Given that’s the case, how do we then enable startups and innovators to innovate more and innovate effectively? What is the right environment where new innovation in technology, and business models can flourish, even though the industry is dominated by a few incumbents with a stranglehold on distribution and small to medium sized farms are incredibly budget-conscious given the state of farming costs right now?

As we stated earlier, Innovation comes from taking more shots on goal, even though the failure rate will be high. (Why don’t you ask Edison, Shultz, or the Wright Brothers?)

What are the right conditions under which more shots on goal are taken? How can we reduce the cost of taking a shot on goal? How can we democratize innovation and risk taking?

There’s no silver budget to solving this dilemma, but here are some ideas to start thinking about

- Develop or support initiatives that increase funding for startups either through VCs or other financing mechanisms, and that focus on building venture studios in rural communities alongside the farmers vs urban centers far removed from the target customer. In addition to that, work to encourage the farmers themselves to invest money into funds targeting AgTech startups so they are fully invested in the company’s success and can act as the “boots on the ground” within the product development cycle.

- Technical infrastructure and platforms to help build solutions (for example, digital platforms, cloud services, etc.). This reduces the barrier to entry to try new innovative ideas to experiment and solve problems. If HighTech companies had more out of the box solutions available for AgTech companies to begin building from, it’d reduce the cost to develop / deploy by not requiring startups to build a full stack solution every time.

- Supporting more infrastructure and models for accelerators, advisors, content creators, forward thinking and risk taking farmers based in rural communities.

- Helping support AgTech programs in land grant universities that target agriculture students, to start to incorporate more technical skills in the upcoming agriculture workforce. Programs like this are always looking for adjunct faculty that work in industry, and you can get exposed to new ideas and potential future hires at the same time.

- Getting behind AgTech companies having more of a permanent presence in rural communities, vs only locating the sales and customer adoption reps in ag towns. Too often, AgTech companies are based in urban areas due to availability of talent but in today’s virtual / hybrid work environment, AgTech companies can be located closer to the farming companies they serve without a risk to their future headcount.

- The Ag industry needs more collaborations between HighTech companies focused on agricultural efforts, start-ups, and farms of all sizes which in turn share findings and best practices to promote cross-pollination across ag companies, farming regions, and commodities. Do you work for a high tech company that could begin reaching out to rural groups?

There’s no doubt another dozen or more ways to get involved, even if you aren’t directly tied to the ag industry. Dan wrote an article on Forbes (link) which covers ways to get involved more in agriculture, regardless of your professional background.

The goal is we can all play a part in driving more innovation in the agriculture industry, as a vertical we can all benefit from. The more we each do our part to increase the shots on goal for the AgTech industry, the better it is for all of us as it’s certainly not an area that will fade over time.