FMS, Thin Markets, and Loss Leaders

FMS are being used as loss markets in thin markets

FMS, thin markets, and loss leaders

I am and have been a vegetarian most of my life. It is not due to religious or environmental reasons, but it is the taste I have developed growing up in a vegetarian household in India.

Janette Barnard is an exciting writer, with an interesting take on innovations in the animal protein value chain. Even though I regularly read Janette Barnard’s newsletter Prime Future, many times I don’t understand some of the issues related to animal protein. Last week’s newsletter was no exception, as Janette called out the challenges with farm management software companies within the commodity row crop sector.

“The major crop input companies acquired these farm management companies to jumpstart their own digital capabilities. By all accounts, these software products were intended to be functional, sustainable profit centers - able to stand on their own two feet like a real grown-up business.”

“My hypothesis is that founders of Agtech 1.0 companies, and investors, had the hypothesis that farm management was a winner-take-all market. If you believe that only 1 or 2 players will dominate a market, then it is logical to invest aggressively in growth in order to be one of those winners.” (highlights by me)

Janette is spot on in her analysis of a flawed market being a winner-take-all market.

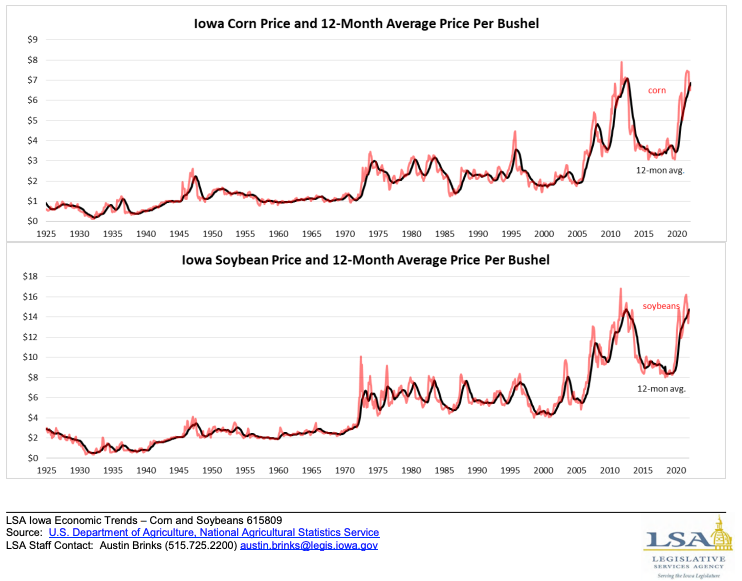

The faulty winner-take-all assumption was compounded by a few other factors. When Monsanto acquired The Climate Corporation, the assumptions on productivity improvement through analytics were in the range of 15-20 bushels per acre, when the prices of corn and soy were some of the highest prices in the history of commodity markets.

Image from following source

Even as late as 2017, it was common to talk about improvements in profitability of $ 100 per acre, based on farm management software analytics. It created an overhang on farm management software companies like The Climate Corporation (full disclosure - I worked there from 2017 to 2020), and Granular. There was a belief about creating a data flywheel to continue to drive more value and in turn bring in more data from commodity row crop farmers and drive even more value.

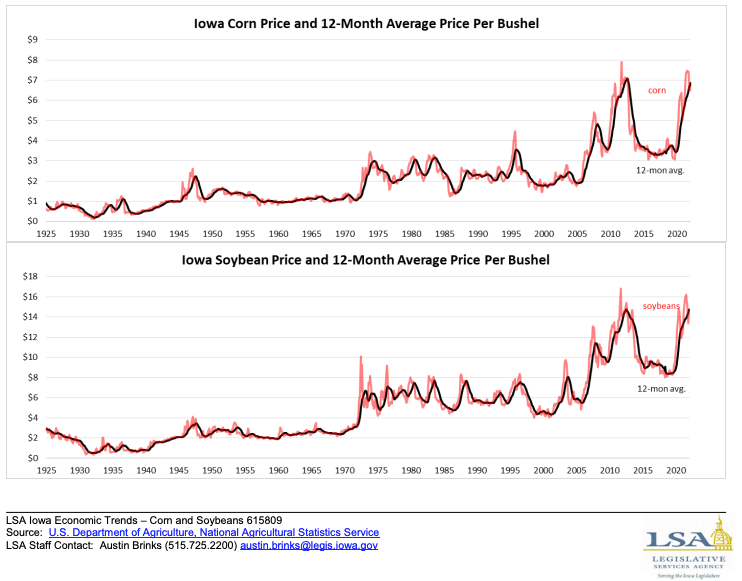

As I wrote in edition 117 and 118, (Thin markets in commodity row crops), and as pointed out by Janette, the diversity among the 200K commodity row crop farmers in the US, make the market even thinner.

The reality was a bit different.

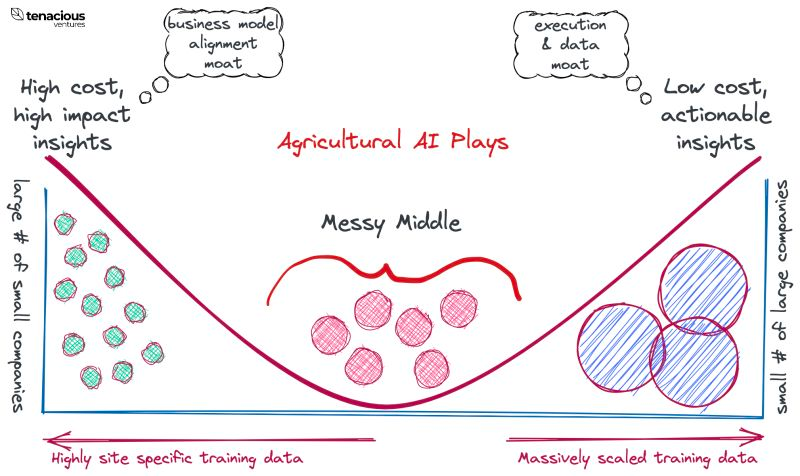

Even though the commodity row crop market is quite big in production volume, and dollar terms, it is characterized by a few buyers and few sellers. It is basically a thin market, with about 200,000 corn and soybean growers in the US.

“We have not seen a strong data flywheel effect in agriculture as it is very difficult to get leverage without distribution. Access to distribution is controlled by incumbents and due to the existing physical infrastructure and relationships.

Even in a technology business in agriculture, the marginal costs don’t go to zero or decline at a fast enough rate. It makes the entry of new players difficult. Given the not-so-large number of commodity row crop farmers in North America, there might not be enough business for a new player to reduce the marginal cost of a new customer to a level which makes unit economics sustainable.”

But the hypothesis on value identification, value creation, and most importantly value capture were very high. The cost of customer acquisition was quite high compared to the lifetime value of a farm management software customer, if you evaluated it as a stand alone business. This was true even for a company like Bayer, with a large distribution network, and strong grower relationships.

Even if the farm management software was able to identify and create high value, due to the complex nature of the open system of agriculture, it was very difficult to attribute the value created to the software. This made value capture from the potential value created by the farm management software quite difficult. Charging a high price for the FMS applications was not feasible, nor was it feasible to do value based pricing.

To make matters worse, the value identification and value creation were hobbled due to lack of good quality data coming from the farm. The precision agriculture data coming from planters, and combines often has many data quality issues, which makes robust and repeatable analysis quite challenging.

In an open system, many different factors like seed genetics, weather, soil, practices like fertility, pest and disease have an impact on the final outcome. The challenging problem of decomposing your final outcome (for example yield) into its components is made even more difficult due to bad and incomplete data, and a difficult data entry user experience.

In such an environment, it makes sense that many independent farm management software providers have faded away, or have been folded into the digital offerings of large input providers of seed and chemicals (for example, Bayer and Corteva). The FMS applications from input companies act as a loss leader, and help make digital connections between input sales people, agronomists, and service providers and growers stronger. The FMS application provides better service, and increases the lifetime value of the customer (LTV) through larger share of their input basket, or higher brand loyalty.

For example, when I worked at Bayer, the introduction of Climate FieldView for Channel seed customers led to increased share of the seed basket, higher lifetime value through brand loyalty, and more than offset the cost of providing the software to those customers.

Due to this standalone software FMS companies have struggled, mightily as they didn’t have anything to sell other than software to recoup their investments in software, and customer acquisition/retention. Famously, Farmers Edge has crashed and burned (They had many other issues. Please read Shane Thomas’s excellent analysis on Farmers Edge)

Having said that, many improvements have been made in the data capture experience, organizations have learnt some lessons on how to get good quality data. Janette rightly concludes,

“It attracted capital and talent to a previously overlooked space. And even though you can't point to individual significant long-term successes in this category, we can safely assume the learnings that founders, investors, strategics, and farmers had through this process has informed how Agtech 2.0, 3.0, 4.0…25.0 will play out.”

I believe markets and solutions often go through many iterations, and pivots before they figure out the right business and deployment model. Even though the first iteration of FMS startups and applications did not fare well, it has led to an inflow of technical talent to the space, changed the thought process for many agriculture companies about the role of technology in their digital transformation, and the lessons learnt have been included in the new models.

The FMS applications have provided a baseline of data for other applications along the supply chain which would not have been possible without farm level information.

For example, Bushel acquired Farmlogs to help connect post-harvest workflows with farm level information, CPG companies, and grocery retailers can help understand farm level practices in their sourcing, crop insurance companies can improve the entire crop insurance workflow of reporting, policy management, and claims adjustment much more efficiently, equipment dealers and OEMs can service their customers better, offtakers can source grain based on certain farming practices, and many other applications. So even though standalone FMS investments might not have recouped their money, it has set the baseline for many applications in the future.

We have an interesting future ahead of us, with many more lessons to learn, and many more mistakes (hopefully new ones) to make.

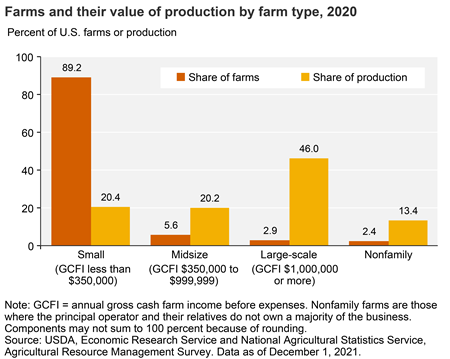

Smile curves

J. Matthew Pryor and Sarah Nolet of Tenacious Ventures are two of the foremost thinkers in the Agtech space. Tenacious Ventures has published a podcast episode on Machine Learning as a Service within agriculture and AgTech. Do give it a listen.

As part of the analysis, Matthew Pryor published a smile curve by drawing on some of the analysis done by technology analyst Ben Thompson (Stratechery fame) in 2014.

“A smiling curve is an illustration of value-adding potentials of different components of the value chain”

The smile curve does a very nice job of addressing the question of if agriculture AI has a need and a market or not. You should read the Twitter thread posted by Matthew.

Matthew has been a proponent of the “factory (farm) has no roof” and the hypothesis that remote sensing will be able to solve/address 80% of the questions at the farm and field level.

“Agriculture that is digitally native operates on the assumption that all required information is available at the highest possible spatial, temporal and spectral resolution. Decisions no longer need to be framed and constrained by the partitioning established around industrial-era infrastructure. Pervasive, inexpensive, high-resolution imagery is available for the entire plant, every day. Complex statistical and machine learning computer models can use this and many other massive data sets to build increasingly accurate models of the real world - the factory has no roof.”

This requires significant investments to capture high quality ground truth data at scale, train machine learning models, and deploy them globally to provide low cost actionable insights. An example of this would be to provide a crop type model at the field level, by using remote sensed data. Due to this companies, which can procure data at scale, and turn them into low cost insights will be able to provide a differentiated product.

This is easier said than done, as I had pointed out in edition 89. (Jan 16, 2022)

“There is a large amount of remote sensing data available from satellites, weather data, etc. to assess crop health, and run different models like cover crop & tillage presence, field boundaries etc. Even though this data is easily available and fairly inexpensively at scale, the data still has many challenges. There are multiple bands, clouds create issues, presence of water vapor, revisit rates, and limitations on resolution create challenges for analysis. It requires a significant amount of preprocessing, with specialized skill sets and experience to get the data ready for analysis.”

“It is as if the factory has a glass roof you can see through, but the glass is smeared with smoke, bird poop, and leaves, making it difficult to see what’s happening under it.”

Companies still need to invest in significant resources to clean up the roof, and also to collect high quality ground truth data (or clean it) coming from precision agriculture equipment, and other sensor types with different data modalities.

If this clean data is provided to other innovators, and customers, value can be captured in terms of efficiency improvements in building models and deploying solutions. Similar to the earlier discussion about value capture, attribution to value created to these models will be challenging and ML service providers will have to come up with creative solutions to do so.

The other side of the smile curve, requires high fidelity ground truth data to provide localized high impact solutions. This could see the prevalence of many small players which provide point solutions, or a few providers with an efficient engagement and delivery model, which includes human support and expertise to help you handle your slightly unique situation, coupled with flexible yet simple pricing models. As Matt points out the differentiation, and defensibility on the left will come from business and delivery models, and not entirely from technology differentiation.

Four investors on What’s next in Food Tech and AgTech

1. Agriculture without reducing soil quality

This feels obvious. Technologies like automation, smaller equipment, biological products, and market interventions like incentives for sustainable agriculture will help with this trend.

2. Differentiated plant-based products

Even though plant-based products like plant-based-meats have taken a beating, these companies need to innovate more to provide plant based products which consumers want and at a price point consumers will be excited about.

3. Regenerative farming techniques

VC Isabella Fantini thinks “investments will go toward technologies that are a little "less shiny" meaning there will be more interest in upstream technologies that are closer to the farmer & through the supply chain, rather than downstream toward the consume.”

Regenerative farming techniques like no-till have seen rapid adoption, though use of cover crops has lagged. Cover crop efficacy is very context dependent, and cover crop adoption will grow only in situations where it provides either a clear incentive to adopt, or provides economic, agronomic, or environmental benefits on a reasonable time horizon.

4. Food as Medicine

I personally detest the idea of “food as medicine.” Food is meant to nourish us. Food is a huge part of our culture, and identity. Food is a connector and a source of joy, when you have the right kinds of food, in the right quantities, at the right price.

I don’t like the reductive idea of food as medicine. Just like medicine, it takes on the meaning of trying to fix something which is broken.

We should celebrate food in all its glory, and work towards making nutritious, high quality food available in the world. Anything else will be a difficult (medicine) pill to swallow.