"Salinas, we have a problem"

Network operations centers in agriculture

I had the privilege of attending the FIRA 2023 agriculture robotics event in Salinas last week. The most fun part of the event were the live demos by different agriculture robotics companies. I didn’t attend the event last year, but based on anecdotal evidence, this year’s demos were much better organized and most of them actually worked. Most of the demos were about precision application (spraying, laser weeding) or precision operations (mechanical weeding). The most interesting to me was Farm-NG which provides inexpensive open-source designed equipment to address the needs of smaller farmers. I will do a deeper dive on Farm-NG in a future edition.

On Wednesday morning, I attended a session with a couple of farmers on the panel. The farmer said very clearly, how important timely support and troubleshooting was for technology adoption. He stated clearly, “Don’t leave your equipment in my field, if you are not going to be around to come and service it in a timely manner, when it breaks down, which every piece of equipment will. When it breaks down, you don’t even need to call me, just come and make it work again.” (We will come back to this before making a detour.)

A strong distribution and service network will be critical for the adoption of any new technology related to robotics, whether it is augmentation or automation. If as a technology provider, you are not thinking about it, you will have a huge challenge in front of you in terms of adoption.

The proliferation of precision agriculture robotics, assuming they work and there is a customer service network to support them, is going to change how farming is done. It will actually change the definition of farming itself. It will change for both large farms and small farms, though in a slightly different way.

But before we get there, let us review what will NOT change, as it is a better framing popularized by one of my all-time favorite CEOs, Jeff Bezos.

What will NOT change?

In edition 99, I had talked about what WILL NOT change in agriculture in the future. I had talked about four human desires, which apply to agriculture as well.

- Our desire for easy and pleasant experiences will not change

- Our desire to lead a stress free life, and spend time with friends and family will not change

- Our desire for others to understand our point of view, and context, and act accordingly will not change

- Our desire to do more with less will not change.

If we juxtapose these non-changes, with some of the technology, social, and regulatory changes, we can start to form some hypotheses on what are some of the mega-trends we will see in the future. Predicting the future is risky, and most predictions turn out to be incorrect.

I believe over the coming years, how farms are managed will change. The definition of what it means to be a farmer or to farm will change, and the number of farmers (based on the current definition) will reduce globally.

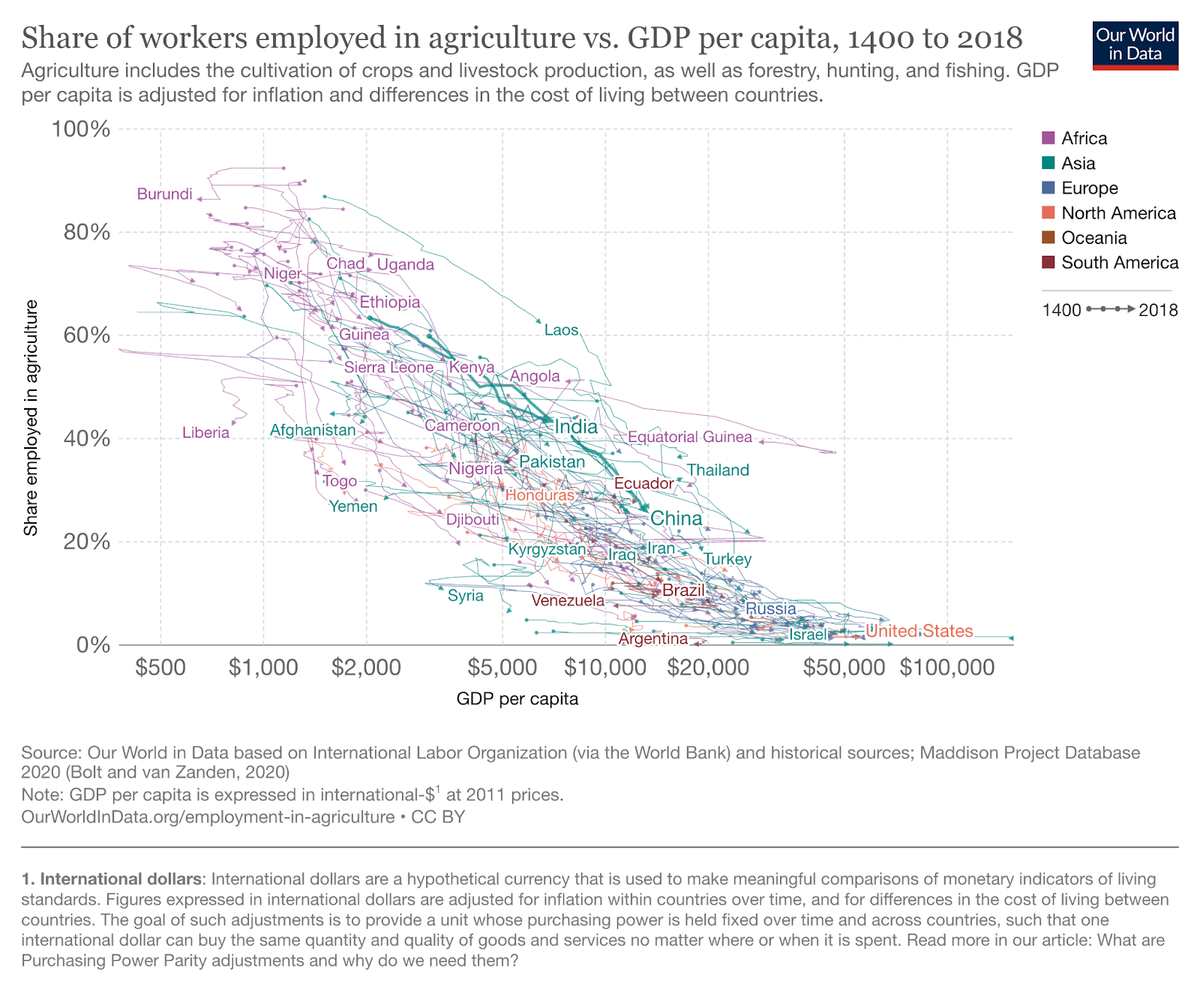

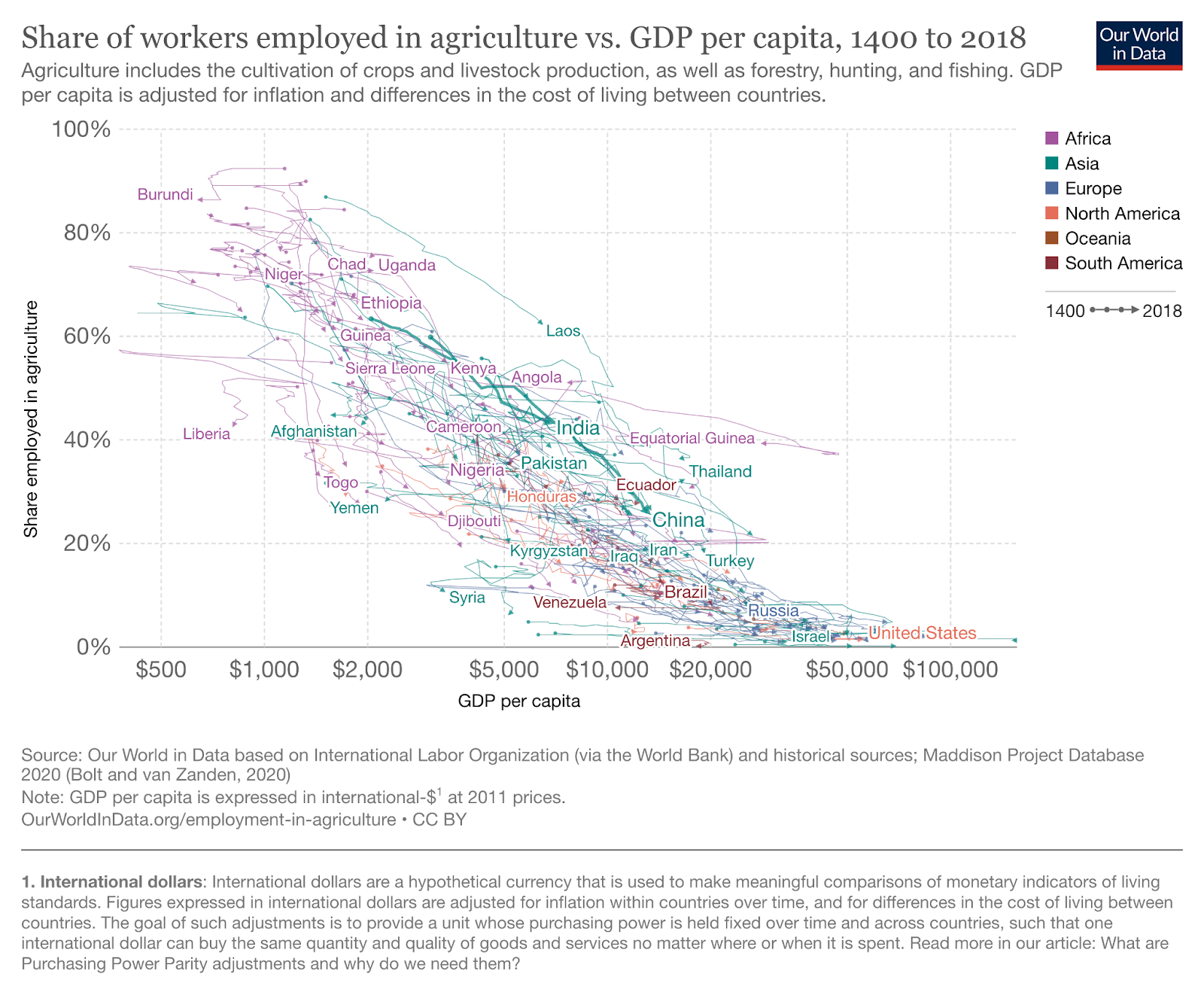

Share of workers employed in agriculture will change

It is a well known trend that as the GDP of the country increases, the share of workers employed in agriculture will change. This is quite obvious as food is a basic necessity and it lies at the bottom of the Maslow’s hierarchy. Once physiological needs are satisfied, human beings move up the Maslow’s hierarchy. We see this behavior at the household level as well. As the annual household income increases, the share of the income spent on food goes down. (This is not entirely true if you consider housing as a physiological need, as many people in expensive areas like San Francisco and New York can spend up to 30-35% of their income on housing/rent!)

As you can see from the chart below, most countries with high GDP are low on the Y-axis.

Source: Our World in Data

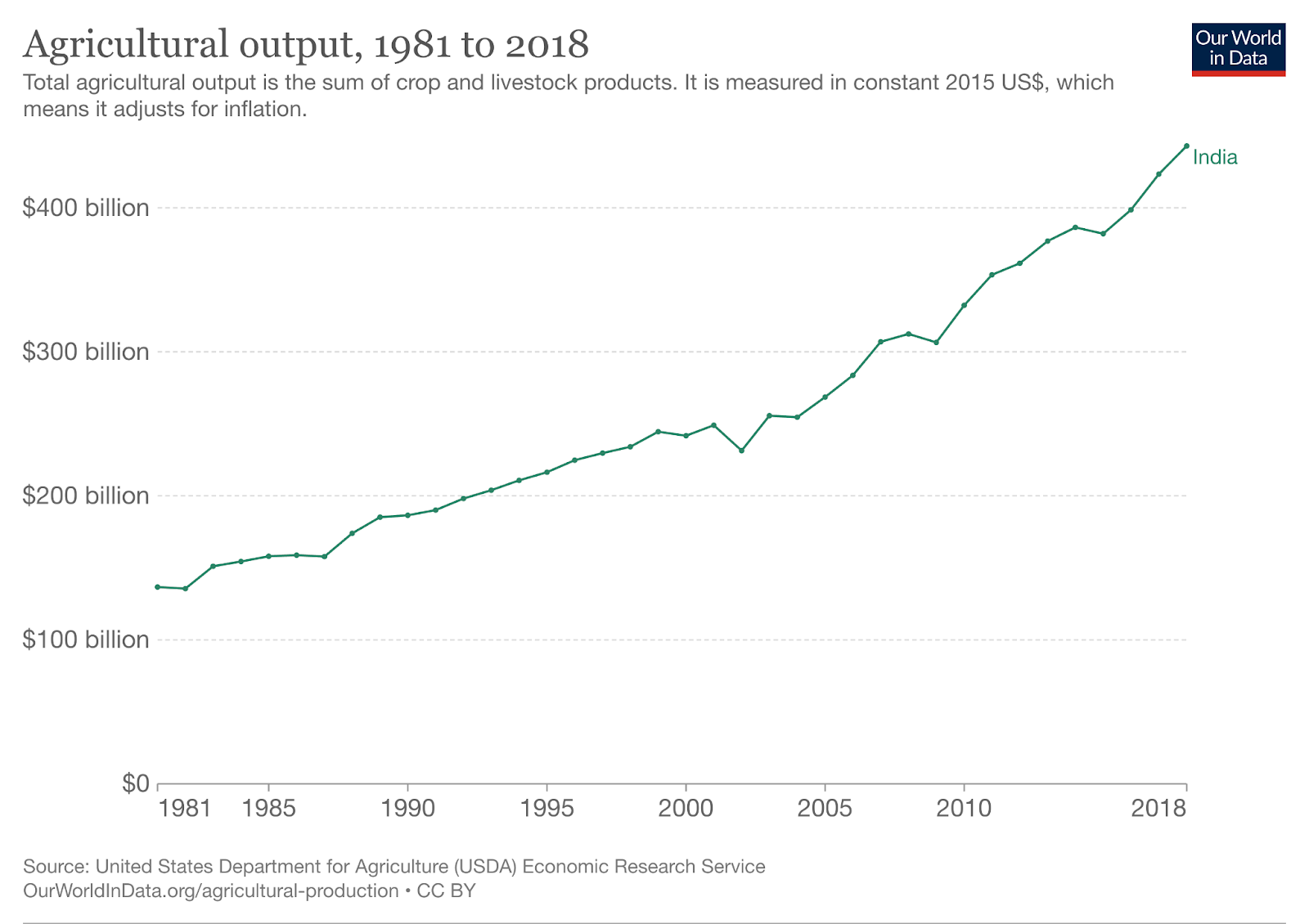

If I take the example of my birth country (India), the share of workers employed in agriculture dropped from 63.3% (1991) to 43.3% (2018), when the GDP went from $ 2062 (1991) to $ 6806 (2018) in 2011 dollars. The agriculture output in the same time period went from $ 136 billion to $ 443 billion.

The population of India increased from 888.9 million to 1.37 billion people in that time period.

The change was driven by a change in economic policies, other employment sources outside of agriculture, and technology changes.

Source: Our World in Data

In a country like the United States, where only 2% of the population is involved with farming, the potential to drop that percentage lower is limited.

Technology will change the number a bit in the future in the US, but most of the changes driven by technology will change the definition of what it means to farm, and how farms are managed.

How farms are managed will change

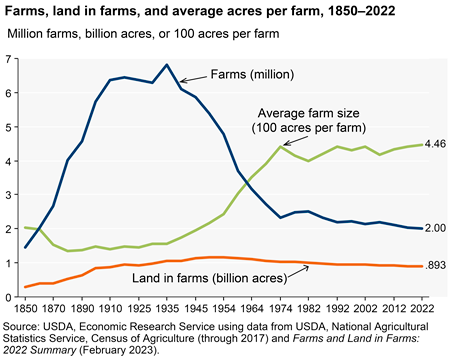

Consolidation in farms has been going on slowly for the last 50 years, with a rapid consolidation happening from the mid 1930s till the mid 1970s.

Source: USDA

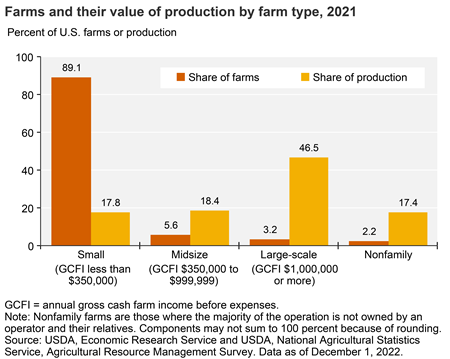

If you look at some numbers from the USDA on farms and their value of production by farm type, almost 90% of the farms are classified as small farms, and account for about 18% of the production value. Large farms and non-family farms (corporate farms) are only 5.4% of the share of farms, but account for about 64% of the share of production.

Source: USDA, Farming and Farm Income

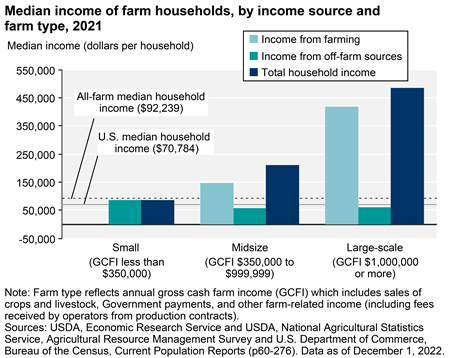

What is even more interesting is how these “small farms” make money. If you look at the chart below, the Gross Cash Farm Income for small farms is negligible, and most of the household income comes from off-farm sources. When I worked at The Climate Corporation (Bayer), it was common for most midwest employees to own and operate a family farm, while working full time for Bayer.

Source: USDA, Farming and Farm Income

Many of the farm owners do not even operate their farm, as they rent out their farm to someone else. In cropland, more than 50% of the farmland is rented.

When it comes to technology adoption within the US, many of the big tech trends we talk about like robotics, automation, selective application of inputs, precision agriculture have often been targeted towards large operations. The initial high cost of technology adoption makes it difficult for small farms to adopt new technology.

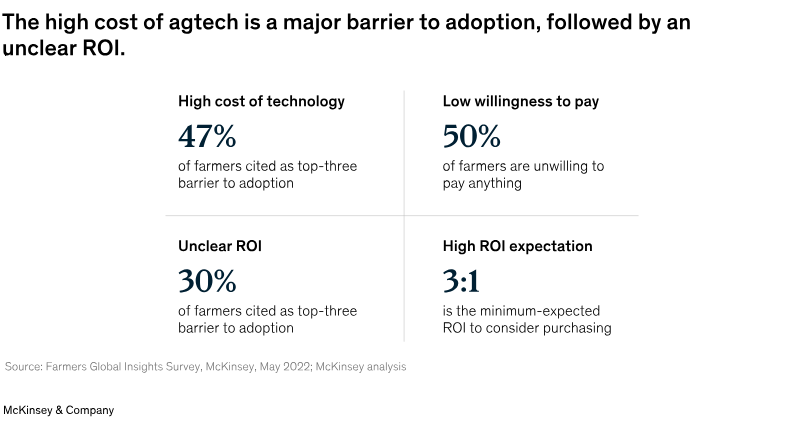

As large farms adopt newer technology, they will continue to be more efficient According to the 2023 McKinsey study, “Agtech: Breaking down the farmer adoption dilemma”, the high cost of AgTech continues to be a barrier to adoption, followed by unclear ROI.

“Across all markets, large farms—more than 5,000 acres—are the most willing to adopt Agtech solutions (81 percent), with 76 percent of medium farms (2,000 to 5,000 acres) and 36 percent of small farms (fewer than 2,000 acres) using or planning to use at least one technology in the next two years.”

In the same report from McKinsey,

“The number of small and medium farms with limited adoption in the developed world presents a significant market opportunity, though product offerings would need to be tailored for these operations. For farms of all sizes and income levels, ease of access would enable agtech’s potential to positively impact livelihoods and the environment globally.”

There is an opportunity to provide a different business model, especially to small and medium size farms. It could mean consolidation with those small farmers getting out of farming, and service based models.

It will change what it means to farm in the future.

What it means to farm will change

When I called Petsmart to get a grooming appointment for my pup Biscuit, till last year the call was answered by someone directly at our local Petsmart location. (I wish they fixed their crappy app so I could make appointments online) In the last year, the call now goes to a central customer service center, for all appointments. I am totally for the efficiency of a centralized operations center, though there is some loss of familiarity with Biscuit’s personality from the local staff.

When I worked with Menlo Logistics about 15 years ago, they operated a networks operation center in Aurora, Illinois. The operations center was responsible for tracking and helping the entire network of Menlo Logistics carriers for certain programs. You could see different trucks, rail carriages, and their cargo on the screen, and the staff at the ops center managed the entire network.

The idea of a centralized operations center is not new. It has been around for quite some time.

The movie Apollo 13 based on the real life Apollo 13 mission, popularized the phrase “Houston, we have a problem.” (The original quote from astronaut Jim Lovell, played by Tom Hanks was in the past tense) The dialogue is between the mission in space, and the Mission Command Center in Houston, responsible for tracking, and managing the entire mission.

Why are we talking about all these examples?

The relevant question is if this model will become much more prevalent in agriculture. I am not talking about just centralized customer support locations, but true network operations centers, which are remotely managing and operating a network of farms. It can radically change what it means to farm in the future.

In edition 52, I interviewed Mark Young, ex-CTO of the The Climate Corporation,

The notion of what it means to be in agriculture will change over time. You could be a “farmer” and work in a warehouse. (You could be a farmer, and work in a network operations center.) Even in broad acre production it'll change because as autonomous equipment and automation takes over, what it means to be a farmer will change.

Salinas, we have a problem

For small and medium sized farms, which find adoption of technology products too expensive, a services based model makes more sense. One can imagine a network operations center set up in Salinas, remotely managing a large portion of the operations through autonomous equipment on the ground.

This can be a services based model, where the farm owner is paying an annual subscription fee with different services bundled in it to the service provider. The farm owner chooses from a pack of different offers, like a Netflix subscription. The service provider is operating the network operations center in Salinas (or Des Moines) to manage and service a network of adjacent but independent farms.

The operations center owns and operates a fleet of equipment, which includes autonomous planters, autonomous selective sprayers, semi to autonomous scouting and spraying drones, autonomous harvesters, which are supplied with inputs like seed & chemicals, biological products, from a regional distribution center.

Cameras mounted on equipment, stationary cameras in the field, and IoT devices provide a constant stream of information and intelligence back to the network operations center. Artificial Intelligence models, supported by large amounts of real data from the ground, constantly make real time decisions with minimal or no human intervention.

The network operations center monitors and manages operations across hundreds of small and medium sized farms. The farm owner gets a regular report on important events, and can hop on their smartphone to see real time operations in the field, while watching their kids Little League baseball game. The farm owner can also login and get latest information on product trials being run, to build confidence in the decisions recommended by

The operations are operated by a small crew of trained engineers, soil scientists, product experts, computer & data scientists, drone pilots, and autonomous equipment experts.

When something goes terribly wrong on the farm, the farm owner/operator is going to make a call to the operations center to say, “Salinas, we have a problem!”

This call will start a chain of reactions, to try to fix the problem for the grower as soon as possible, and provide regular updates along the way.

Custom Crop Services

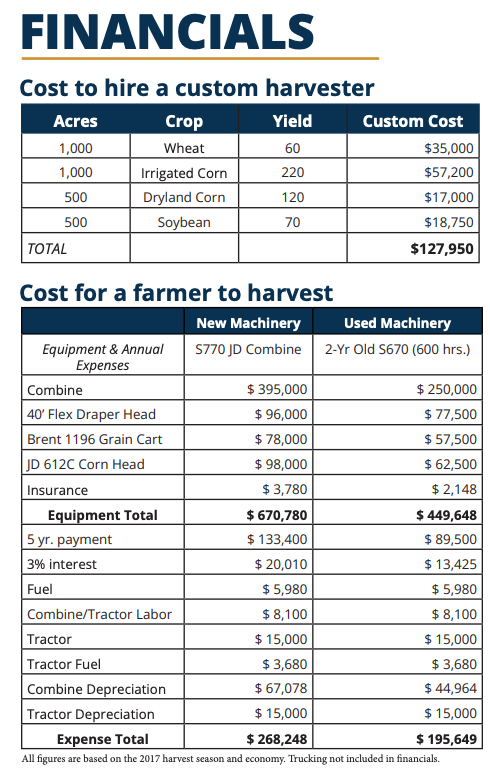

We already see the prevalence of custom crop services providers, who market their service along two dimensions.

First, for a certain type of farmer, a custom crop harvester is shown to be more economical than the farmer owning and operating their own harvesting equipment.

/content/files/why-hire-a-harvester-2022.pdf

Second, custom harvesters tout the availability of modern equipment, and the labor with the technical skills, and experience to operate and provide a reliable, and valuable service.

If you are a farmer who fits within this category (based on the acreage, a small to medium sized farm), unless you absolutely love owning and operating equipment, there is no reason to not go the custom harvester route. (Assuming the custom harvester can provide services aligned with their promise) As you can see, economics go hand in hand with a reliable and trained crew who can provide these services in a timely fashion.

My friend Connie Bowen, rightly mentioned this in edition 4 of her newsletter, “Agriculture is for people” (I wish she published more frequently as she has such great insights) by highlighting the challenges for robotics companies in the specialty space.

“RaaS (Robots as a Service) has become kind of the go to business model that ag robot startups talk about. If a company can manage to fundraise adequately and build a team that both has excellent technical capabilities and service capabilities while still having a route to profitability, more power to them. Unfortunately, it’s really hard to do that, and selling to high quality service companies might be an easier and more impactful strategy.”

Connie goes on to write about FLCs (Farm Labor Contractors), which are much more prevalent in the specialty crops, but the general principles apply to any cropping system in the developed world.

“I believe that there will be a next generation of FLCs. Those “Next Gen FLCs” can invest in technology, specifically equipment solutions, to enable their employees to be more efficient. They can invest in software solutions to make their own administration and their farmer customers’ lives easier. They can expand their margins by delivering highly efficient services using fewer people. Talent attraction and retention is the most important differentiator in agriculture labor markets right now, because there simply aren’t enough experienced people interested in doing this work right now. Next Gen FLCs can attract talent by investing in their employees, from ergonomic improvements to slight wage increases.”

and she also compares them to existing OEMs,

In addition to existing OEMs, I believe that Custom Crop Service Companies are less traditional channel partners that can and will play a huge role in the next 1-2 decades in driving technology adoption.

Talent attraction and retention is the most important differentiator in agriculture labor markets.

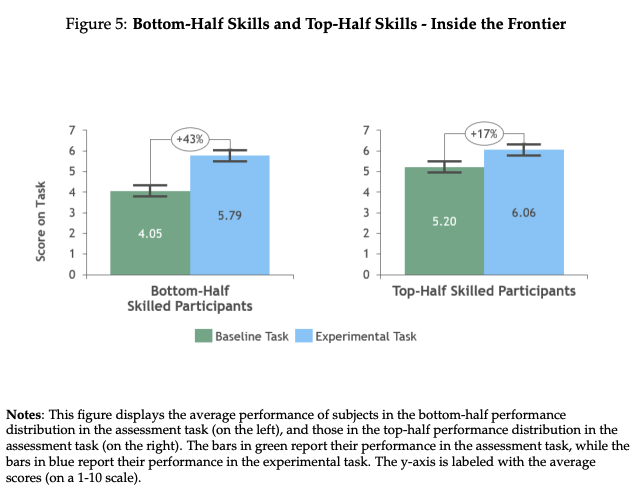

This will require training and retraining employees with different sets of skills. These organizations will have to become learning organizations, as upskilling employees with information will be the easier part, due to the technologies like large language models. Many (or most) of the core digital technologies, a services company (or an agriculture retailer ) can leverage will not be anchored purely in agronomy, but in the customer experience, services sophistication and responsiveness, staff efficiency, and data utilization.

So what are the key takeaways for different entities involved in the agriculture value chain?

New ag-robotics, and precision farming technology companies

- Think and think often about how you will provide customer support, and services for your products in the field. It will never be too early.

- Don’t try to do everything in-house, unless you are capable of doing it. Find the right partners for distribution, service delivery, and customer support.

- During the early days of your product discovery and prototyping, be constantly out in the field with growers, and agronomists. Have conversations with farmers, crop consultants, and be curious. Try to solve problems in a non-scalable way to learn how to scale.

- Experiment with the business model, to what makes most sense for your target customer.

Custom Crop Service providers and Ag Retailers

- Invest heavily in staff training and retraining. Labor shortages are real, and so you need to make the most of your existing staff.

- Identify skills gaps as new technologies come along, and don’t be afraid to lean into newer technologies for LLM for training purposes.

- Invest in people who can form a connection with your customer, are curious, and have a learning mentality, as things will change constantly.

So, when the call comes in, “Salinas, we have a problem”, your staff will be well equipped to handle it.