Sprayers, Drones, and Planes

Pyka's autonomous electric spraying drone

This week’s edition of SFTW includes the following topics

1 Autonomous and electric uncrewed aircraft company Pyka strikes a deal with SLC Agricola

2 MoA and UPL go-to-market deal on herbicide

3 “Divine Discontent”, Blackberries, and Pairwise

4 Actual data on herbicide savings using spot spray technology

Sprayers, Drones, and Planes (Pyka and SLC Agricola announce deal)

There are different methods to apply crop protection products.

Sprayers. Drones. Planes.

Each of these methods have their advantages and limitations.

In commodity row crops, sprayers can cover a lot of ground very quickly, do precision application through technologies like spot spraying, though there are challenges with drift, need of a driver (for non-autonomous equipment), cannot operate in wet soil conditions, and soil compaction issues.

Drones have limited capacity, need constant refilling and recharging of batteries, need an operator, but they can get out quickly, and get to areas difficult to reach by a ground based sprayer.

Planes can cover large areas very quickly, but need a trained pilot, there are safety risks due to wires and trees, and precision applications are challenging.

Crop spraying airplane company Pyka addresses some of the issues inherent with aerial vehicle based spraying through its technology.

Pyka’s second generation spraying Pelican is an autonomous and 100% electric unmanned aerial system (UAS), approved by the FAA to do crop spraying operations in the US, and is also approved by local regulators in Brazil, Costa Rica etc.

Current and potential customers for Pyka

“The US is the largest aerial spraying market in the world with US $ 800 million in annual sales, by an estimate of the National Agricultural Aviation Association. The startup from Oakland, California, sees plenty of opportunities, with crops such as leafy greens and vegetables that need to be well presented on supermarket shelves. Those crops often are sprayed up to 15 times a year.

Pyka says the Pelican offers increased spray precision, reduced chemical usage costs, and minimised environmental impact. “Pyka’s Pelican Spray aircraft is the world’s largest and most productive agricultural spray drone and is already operational on farms in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Brazil”, the company says. “It can carry up to 540 lbs (245 kgs) or 70 gallons (265 litres) of liquid and spray up to 240 acres per hour.”

For comparison, one of the most popular manned agriculture spray airplanes is the Air Tractor AT-502B, which has a 500 gallon capacity payload, and requires a pilot to operate the airplane.

Pyka recently announced SLC Agricola as a customer for their crop protection aircraft.

SLC Agricola is one of the largest agriculture producers in Brazil, with close to 1.7 million planted acres across cotton, soy, corn, and a variety of other crops. SLC Agricola operates processing and storage facilities for cotton and grain. They have a robust agronomy, and technology program in place, including running multiple trials across their 23 production units in 7 different Brazilian states.

I had the privilege to connect with Volker Fabian, Chief Commercial Officer of Pyka a few days ago in response to the SLC Agricola news.

According to Volker, Pyka has spent the time to understand the opportunities with crop spraying, including the risks involved with the process. They have chosen pathways which allow them to take a step-by-step approach to work with regulators in different parts of the world.

The spraying business using aircrafts today is a high risk job due to power lines and trees, mostly done through old aging equipment, and hard to find pilots.

With Pyka’s approach, they are able to address the needs of medium to large scale operations in Brazil and the US where it is not uncommon to have farms which are a few thousand to tens of thousands of acres. For example, within Brazil there are about 2500 aerial vehicles, with most of them being conventional aircrafts. Brazil provides a huge market for a company like Pyka to tap into. SLC Agricola already uses multiple aircraft for spraying purposes, for their 1.7 million acre operation.

Image courtesy: Pyka

Pyka has customers in Costa Rica, and Honduras for banana plantations. Even though the banana plantations are smaller in size (between 2000 to 5000 hectares), they require very frequent spraying. Some of the typical customers of Pyka are in the more than 10,000 hectare range.

On the lower end, Pyka can work with farms as small as 500 hectares, though my guess is it would require either very frequent spraying operations in a given season, or a density of a large number of 500 hectare farms in a given area (or both).

Business Model & Technology

Pyka’s business model is a bit different than the model used by Deere for their See & Spray technology, or a service based model used by manned spraying. Pyka leases the aircraft out to an organization like SLC Agricola over a multi-year lease, with a fixed monthly lease cost. Pyka provides training to onboard operators, customer support, and replacement spare parts as necessary. Given Pyka is an all electric vehicle, its maintenance needs will be much less than an equivalent fossil fuel powered aircraft.

An organization like SLC Agricola can use the aircraft as much or as little as they want, for a fixed lease with Pyka. They obviously have to pay for operators to operate and manage the flying operation, which is a variable cost, but it does not require very expensive licensing and training as the aircraft is autonomous.

With a fully autonomous aircraft, which still needs to be within the extended visual line of sight of the operator, there are some limitations on the range for Pyka.

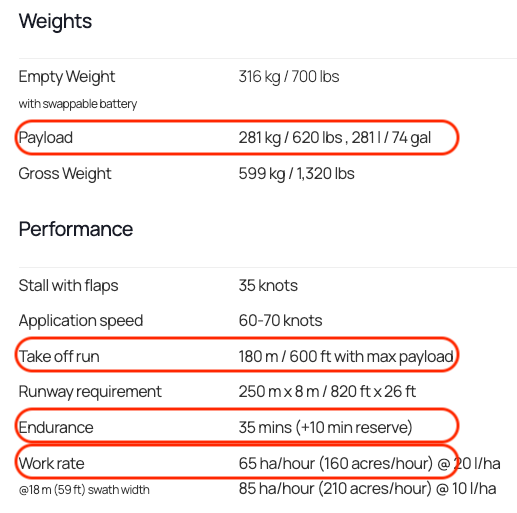

Based on technical specifications from Pyka’s website, the Pelican Spray model can carry a payload of 74 gallons, needs a take off run of 600 ft (an American football field is 120 yards in length, including the end zones), which is a bit less than two American football fields end to end, has a flight time of 35 minutes, and so can cover about 80 acres in one flight. Just like with drones, the limited flying time on a single charge is one of the biggest limitations of Pyka’s (or any electric vehicle’s) approach.

Image source: Pyka Website

As batteries get bigger, and can be charged faster, they will be able to stay up for longer and cover larger areas. It requires a strong grid infrastructure to charge the batteries, which seems to be available in the case of SLC Agricola.

SLC Agricola is using the aircraft for its own operations, but a service provider or a custom applicator could also lease the aircraft, assuming they have a large density of medium to large sized growers in a given geographical area. It is early days, but due to this limitation, most of the customers (at least the ones they have talked about publicly) are either large corporations like Dole or a large producer like SLC Agricola.

According to Volker Fabian, Pyka has some larger sized models in the works, which will give more capacity to this mode of application. When I inquired about additional use cases within agriculture, Volker indicated there is enough room to grow with the spraying use case.

Drones and Aerial

Pyka will compete with drone based applications on their lower end, as drone capacity goes up. For example, AG-272 drones from Hylio (hybrid powered drone) can cover 50 acres / hour at a 2 gallons per acre rate. (2 gallons per acre is roughly 18.7 liter / hectare, which is similar to the 20 liter / hectare used to calculate 160 acres / hour work rate for the Pyka - please see screenshot above). So three to four AG-272 drones could provide the same capacity as one Pyka.

There are differences in the actual spraying process between drones and airplanes, even though both come from the top, due to various factors like height of spray, downforce, water volume used, droplet size etc. You can check out this video from Tom Wolf of Sprayers 101 to understand these issues, when it comes to spraying by airplanes.

Future growth for Pyka

Given the simple monthly leasing model, Pyka cannot charge the same customer more, unless they add additional value through additional use cases (which it seems they are not working on within agriculture).

For Pyka to continue to grow, they need to find new customers who have large acreage, have frequent application needs, have density of large acreage customers in close proximity, the regulatory environment in a geography is amenable to their model, there is reliable electric grid infrastructure, and Pyka can provide adequate customer support and parts to their customers in a timely fashion.

Note: Kelly HIlls Unmanned Systems plans to leverage their FAA UAS test range to help commercialize advanced spray drones (andground robotics as well). You can see Pyka and other drone spray companies in action and you can request for registration at

https://kellyhills.us/

. (I don’t have any financial interest in Pyka or this event or any other advanced drone spray company.)

MoA, UPL, and the role of AI in herbicide

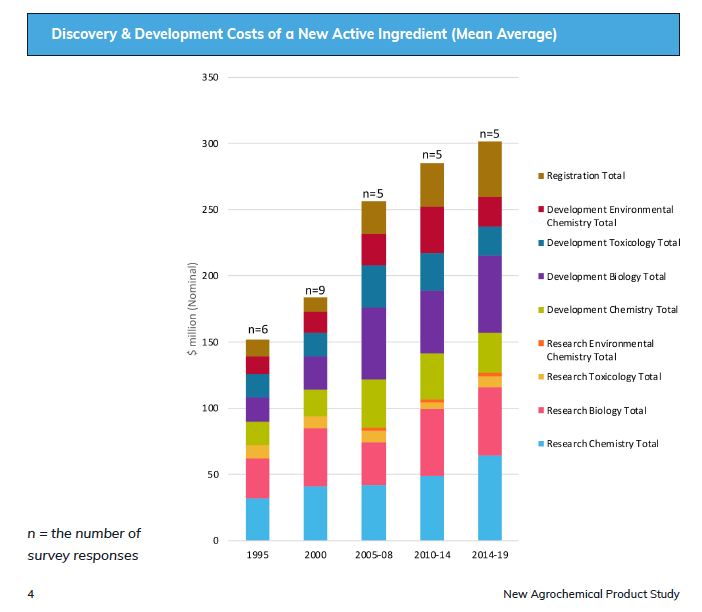

In edition 157. A needle in a haystack, I had talked about how the discovery and development costs of herbicide have been going up for the last 25-30 years. Most agrochemical companies have struggled to come up with new crop protection products, with patents on existing products expiring.

As discussed in edition 157, artificial intelligence is having a positive impact on the herbicide discovery process. The impact of artificial intelligence was felt through accelerated lead identification, protein target identification, binding affinity prediction, designing for selectivity, and safety, overcoming resistance, and data driven formulations.

MoA technologies is showing the receipts.

I had highlighted MoA Technologies as one of the companies working on finding novel models of action and has screened over 75K compounds. They have discovered 60 promising novel modes of action areas, with multiple candidates infield trials post laboratory validation and glasshouse testing.

In spite of the advances in the herbicide discovery process, it is expensive to go through field trials, toxicology testing, and the legal process of registration. It requires special skills, infrastructure, and experience to take promising molecules post discovery to market.

MoA’s recent deal with NuFarm does the same. The deal provides exclusive access to NuFarm to a new mode of action.

“In return, Moa will receive upfront payments, milestone development payments and eventual royalties from sales of the herbicide, which could be the first broad spectrum agricultural herbicide to work in a completely different way in 40 years. Nufarm will also exclusively retain the option to commercialize other Moa compounds from the same mode of action area.

Together Moa and Nufarm will be responsible for steering the new chemical series through the research phase, expected to take around two years, while Nufarm will lead the final phases of development and go-to-market.”

Due to this most startups do not have these resources to take products to market, and they have to rely on larger well-established agrochemical or biological companies to take products to market. Due to this, when it comes to the crop protection discovery process,

- Most startups are playing the role of partners or enhancers of the pipeline, with not many disruptors

- With the use of sophisticated AI tools, there is a potential to improve the quality of hits selected for lead optimization, protein modeling, protein-to-protein interaction to provide better signals for efficacy, residuals etc. and thus take out about 30-40% of time and cost required for the discovery process.

- AI tools are helping identify novel modes of action (MoA) at a faster rate, due to high-throughput screens for new modes of action, mode of action elucidation & chemotype discovery. Only a handful of new MoA have been found in the last 30 years, but AI has helped identify more than 50 novel MoAs in the last few years.

- The agro-chemical industry is applying AI techniques like protein folding, multi-parameter optimization, protein-to-protein interaction models, etc. used in the pharma industry etc. The agro-chemical industry has realized about 20% of the benefits of AI tools used in the pharmaceutical industry, for the herbicide discovery process, and so there are still significant learning opportunities within the agrochemical industry from the pharmaceutical industry.

Divine discontent: Seedless Blackberries with Pairwise

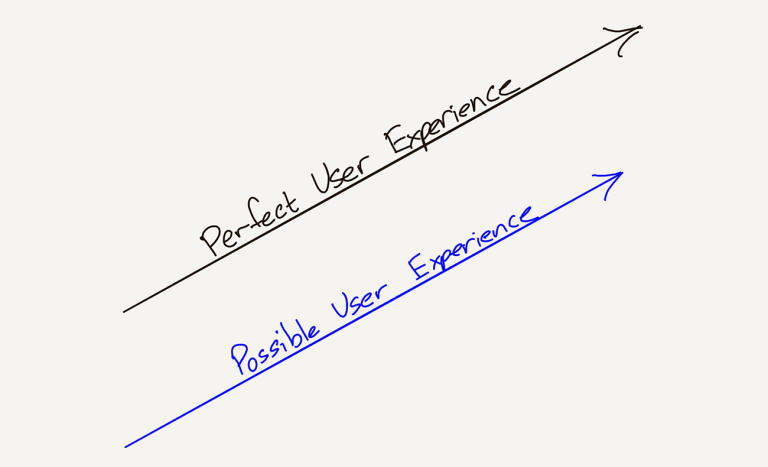

Ben Thompson of Stratechery had written about the notion of “Divine Discontent” in 2018.

Divine Discontent means the possible user experience can never meet the perfect user experience as the customer expectations keep changing and going up in quality as existing products improve.

I love me blackberries! Especially the sweet ones from Driscolls. When you are enjoying those blackberries, you think you cannot get a better blackberry than the one you just had. But many consumers do not like the seeds in blackberries. It is not a “perfect user experience” for them for their blackberries, as about 30% of customers

Pairwise has developed seedless blackberries using CRISPR in plants. CRISPR does hold significant potential in agriculture, and human health as well. Pairwise scientists have used multiplex editing techniques to eliminate the hard pits in berry fruit, to create soft small seeds similar to the ones found in grapes and watermelons (commonly labeled as seedless).

The blackberry plant for this blackberry trait is reduced in height, is more compact, and due to the absence of thorns the harvestability of these plants is here. Pairwise has been able to do this without changing the flavor or quality of the blackberry.

There is a potential to apply similar techniques for fruits like cherries etc. to reduce the size of their pits, which would be so cool.

There is still a long way to go for these types of products to become commercially successful, but this is classic “divine discontent” at work.

Some more real data on herbicide savings

Typical marketing material for spot spraying companies takes the best case scenario on spot spraying, and uses it as their marketing claim. Due to this you often hear marketing claims of 80 to 90% chemical savings due to spot spraying.

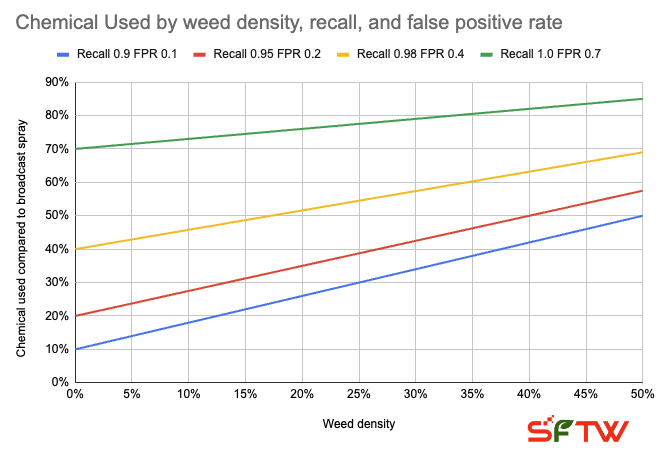

In edition 138. Recall is risk tolerance, I had written about a simple model which includes weed density, recall and false positive rates to come up with an estimate for chemical savings.

Chart by Rhishi Pethe

It is good to get actual data to help understand the potential of spot spraying technology like See & Spray from John Deere. A Michigan farmer has reported savings in the 26% to 60% range. The savings are higher compared to broadcast spraying, when the weed density is lower.

According to the Michigan farmer, weed control programs cost between $ 20 and $ 30 per acre. If we assume a cost of $ 20 per acre, if Deere’s See & Spray costs $ 4 / acre, then 25% is the minimum savings required from your spot spraying program. (This does not take into account the upfront setup costs of a See & Spray system). At $ 30 per acre for your normal weed-control program, the See & Spray system should save you at least 14% for the spot spraying program to make sense.

These actual numbers help calibrate and true up any marketing claims made by different companies, and help customers evaluate which program is right for them, based on the context of their operation.