Kellan Hays: Innovative agri-financing models in Zambia

Good Nature Agro Co-founder talks about Zambian agriculture

This week’s edition continues the “Conversation with Rhishi” series. It features Kellan Hays, co-founder of Good Nature Agro in Zambia, Africa.

“Good Nature is a for-profit social enterprise that believes in farmer-centric impact. It works with Africa’s rural small-scale farmers to supply the region with high-quality legume seed and commodities.”

What we enjoyed discussing

Good Nature has helped hundreds of farmers to be on the path to prosperity through knowledge transfer, financing, and finding buyers for the farmer products.

In working with smallholder farmers, there are both opportunities as well as the challenges, related to financing, know-how, finding buyers, foreign exchange risk, and securing a supply chain.

The use of innovative financing models, which combine cash and kind vehicles, guaranteed offtake, and value share reduces the friction for farmers to participate in Good Nature’s programs for seed and commodities. These programs put the farmers on a path to prosperity.

Kellan and her team are taking concrete steps to provide economic advancement opportunities to women. Kellan is driven by action-oriented motivations, rather than traditional ones around career, family, and money.

Seed sorting at buyback purchase point Vubwi. Kellan in the back (with sunglasses) Photo courtesy: Kellan Hays

Smallholder farmers need full farm support

Rhishi: How did you get to Good Nature Agro and why Zambia?

Kellan: My background and my career has been in social and environmental issues. When I graduated from undergrad, I worked in political organizing and fundraising around environmental issues. I worked at the Jane Goodall Institute to look at global conservation, global aid, as well as youth programs.

I got my MBA at UC Davis, which is where I met my co-founders Carl and Sunday. I worked full time for the Autodesk foundation for six years. Good Nature was my side hustle, on nights and weekends and my labor of love.

Two years ago, I went full time with Good Nature. I'm so happy to be here. Carl and Sunday, my two co-founders met in 2013 at a design and innovation summit in Zambia.

Sunday is Zambian. Carl was getting his master's degree in soil science at UC Davis. When Carl came back, I met him through a class through D-Llab. We were children of D-Lab and human-centered design.

We started in Zambia because we understood the local context (Sunday is Zambian.) It was an interesting time in the country. The GDP was strong, the currency was strong, but the government was changing policies around maize. A lot of smallholders were going to be left behind when these government programs changed.

Our original hypothesis was to play the maize market [pricing] and work on crop storage. We quickly realized that it was more about crop diversity. It was about proper storage. The legumes in Zambia did not have great seeds for us to do what we wanted. We quickly moved into seeds, which is lucrative for the farmers.

Rhishi: Who are your customers?

Kellan: When you look at the maize markets in Zambia, they are government driven. Maize is the largest crop in the country. Most farmers monocrop maize. It is a political tool to get people re-elected, to donate to food programs etc. But the power of legumes is that they are good for the soil and pocketbooks. It has a longer term value for farmers.

We do sell into some government contracts. We want to get away from the political environment as well as the slow payment process from the government, though it comes every year. But it's unreliable and that the cash flow could be delayed for any reason. So the innovative and exciting sales structure for smallholder farmers is part of our impact mission.

We started with seeds. We realized that for a farmer to switch and grow a different crop and be successful, they need full farm support. Fortunately, we had been doing that for a number of years in our seed model. We were financing the seed for our farmers.

We were guaranteeing off-take. We were providing agronomic training and infield support. We knew how to build up relationships with these smallholder farmers. It became a seed plus services model.

We do have plenty of other segments that we sell into. For example, export, government, agro dealers, etc. We work across the value chain and plug the smallholder into more pieces.

Our position as a seed company means that we get to breed and select varieties that work well for smallholders. They are smallholder-friendly and they are what the end of the value chain wants.

We are able to take that to the beginning of the cycle and put it through our seed program. We call that our source model, which is the customer sales model. We are excited about it and that's where the business is headed.

Doing business with smallholder farmers

Rhishi: You talked about crop diversity and how crop rotation is not common in Zambia. How does that compare with other African countries?

Kellan: There is a big difference between Zambia and countries like Kenya and Tanzania. The farmers we work with have about three hectares of land, which is many times more in Kenya or in Tanzania, for example. It allows our farmers to take a little bit of risk.

We don't contract more than half a hectare with a farmer in their first year. They get agronomic training, helping them grow their maize or their cotton or their tobacco better. They get soil science information from us, great support, and they are growing with a portion of their land. It is a bit risky, but a small pilot. So that is one of the major differences. The amount of land grown in tobacco within Zambia has decreased by 30% in the past couple of years. With the tobacco industry shrinking, and a lot of government programs and incentives are trying to push people towards legumes or other crops besides filling it in with maize. It has bolstered the industry and increased competition, which we are happy about.

We have a grower ratings program which started with our 4500 seed growers. It will start with our commodity growers, where we build a year over year relationship with them. There's a little bit of soft skills and a little bit of quantifiable rankings. They are able to increase land with us. They are able to take on additional loans, say with fertilizer and additional crop types. Currently all of our farmers are growing one legume type with us. But as they get more skilled and can build their business with us, we can bring in additional services.

Rhishi: You said that your seed breeding program is smallholder-friendly. What do you mean by that?

Kellan: The legume varieties that are the most popular in Zambia and Malawi are local varieties that have been around for a long time. If you're going to grow a crop for income, you're looking for crops that are drought resistant, climate change-friendly, high yield, are dense and have shorter growing times. It has been a differentiator for us to breed and release seeds that have shorter growing times. It gives farmers a little more wiggle room with the rainy season.

They have a little more wiggle room to plan that timing with their crop. At the end of the season, they get money earlier compared to groundnuts or other beans that they are growing.

Farmer training: Photo courtesy Kellan Hays

Rhishi: The cashflow for the farmer is patchy. How do you help them manage that process?

Kellan: It's hard for us and for them. Another big difference between us and Kenya or Tanzania is that we have one growing season. So each year is a whole business cycle.

One of the key ways that we are helping farmers even out their cash flow is that we do a payment plus premium. It is a revenue sharing program where we pay our farmers upfront at a base price that is usually around 30% more than they would get at selling at a good commodity rate. (It is 3X of selling maize)

They get that base price, when they sell. Then a couple months later, they get a second payment premium based on the sales price that we are able to garner and the success that GNA would have on processing and selling their seed.

We are finding that farmers are buying big ticket items from their first payment - a new bike, a new roof, school payments. They use the second payment for next year's or season's investment. We have been piloting different savings programs and bringing in interesting partners to help farmers do even more and try to save their way into the middle class vs. lend or borrow into the middle-class.

Rhishi: Who are these financial partners? How do you convince them that your model is less risky or is better suited to their business?

Kellan: Our biggest partner is PayCode, a digital savings plan and payment card based out of South Africa. We are their first partner in Zambia. We are able to get 4,500 farmers enrolled in a payment card and savings process this year. It is cash driven and our business model has been built off of in-person, high-touch engagements, which have been why we have been so successful. To give you some context, the government extension agent model in Zambia is 1 agent for 3000 farmers. Our model is 1 to 40 with seed, and 1 to 80 with commodity. So high touch is where we spend our money.

Rhishi: What is the proliferation of smartphones among farmers?

Kellan: About 70% of the households in Zambia have a mobile phone. It goes down as you get to more and more rural areas. For our farmers, we are collecting phone numbers and planning engagement with whatever mobile phone they have access to. We are not saying it has to be one that you own. It's the one where you can receive information and that could be a friend's phone. We are trying to lower the barrier for communication as field connectivity is extremely poor.

We are not an agtech company (agtech = technology used in agriculture). We are an agriculture company that is using technical platforms and technical solutions to help us make better decisions, connect the people and connect to our mission.

It is a farmer tracking solution that is not a two-way communication. But because we have year over year relationships with our farmers, we are able to set financial goals with them, talk to them about their performance last year, about their soil health and match them to the seeds and inputs for their land and their goals. The idea is to do that at an increased scale along with a two way engagement with our farmers, where we are able to send pricing information or pest guides we usually send directly to our lead farmers, but get more penetration to farmers.

Rhishi: You talked about how it is difficult to source from smallholders. How do you select farmers for your seed business versus your commodity business? Are there differences between these two types of farmers?

Kellan: They are not that different from your average farmer. On our seed side, people need to have a little bit of an appetite for risk, enthusiasm and want to try something new. It wasn't about how much money you have in the bank.

We met our first hundreds of seed farmers through non-profit networks. They finished their grant funding and didn't know what to do with their farmers afterwards. We said, we will adopt them, let us see if we can bring them into the seed fold. So that's the first customer acquisitions for us. Then we grew geographically from there on the seed side was an in kind loan. It was more about your appetite for risk and your perceived talent.

Seed is more technical than commodity. So they needed to show a bit of agricultural chops, but with our high touch model, we helped people succeed. We have a long waiting list of people who want to become GNA seed farmers in our districts.

We are upfront with people about turnover, which is small. On the commodity side, it's about network partners, the ability for farmers to make a deposit, to contribute towards their seed loan.

Inclusive smallholder financing models

Rhishi: What are your financing models?

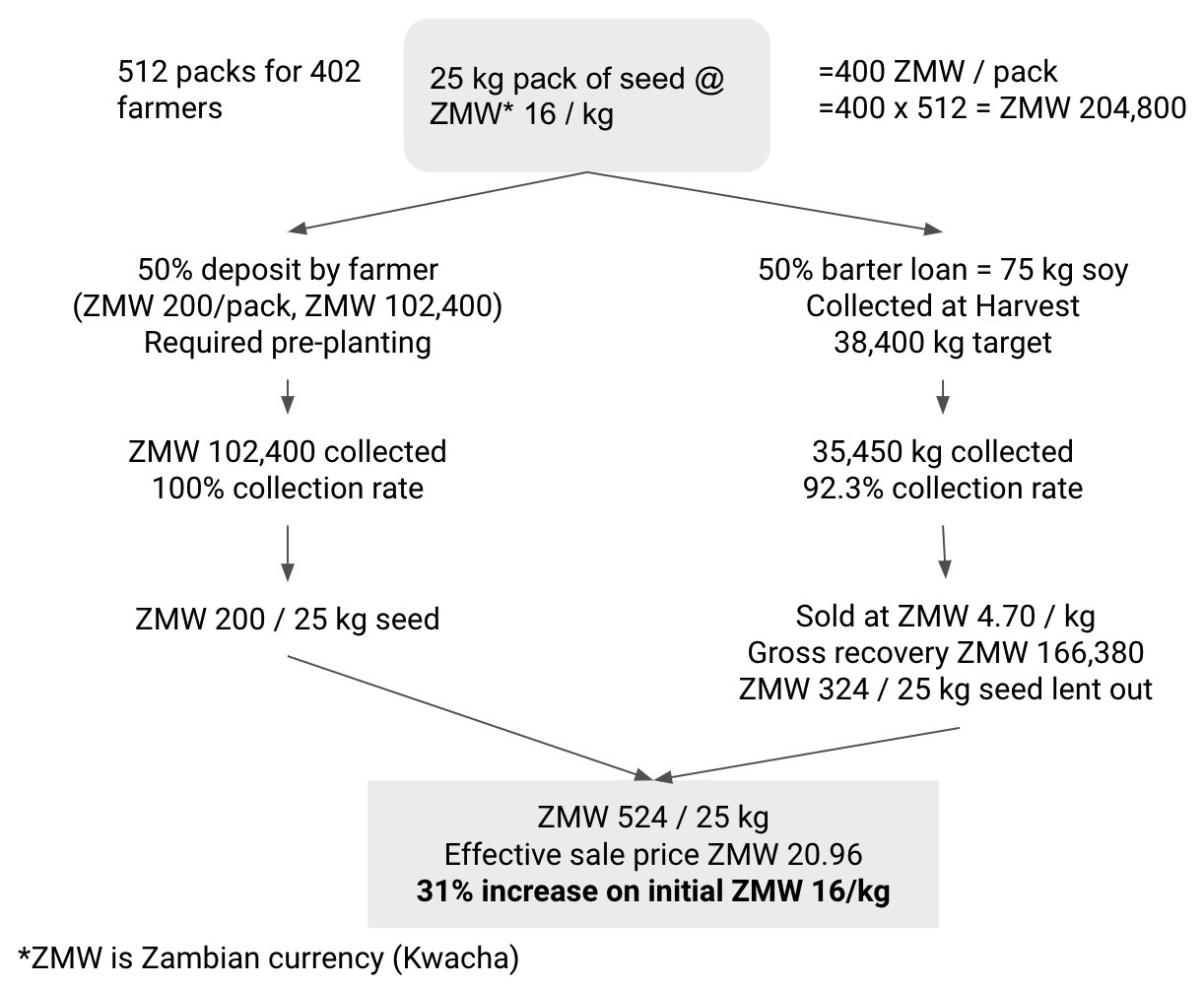

Kellan: On the commodity side at scale, Good Nature could not take on that type of debt. The commodity margins are so much lower. We couldn't take on additional debt. We have worked out three different financing models.

The common thread throughout them is that farmers have to contribute upfront to that seed purchase. It is a way to segment the population. Not everybody is there and able to contribute.

But the hope is that by being in the community and helping to increase incomes, we can bring on more people.

One is a barter method. So the farmers contribute 50% and then we finance 50% of the seed and they pay us back for that in “crop”. So it's a 1 to 2.5 loan. So for one kilogram of seed, you give us 2.5 kilogram of crop. It keeps the cash transactions and the loan on our books down. It has a little bit of interest packed in because we get the sale price for the crop.

Example of a hybrid financing model by Good Nature Agro. Source material from Kellan Hays

The other model is a little bit barter and a little bit revolving. We call it a revolving fund. We have our network partners and the majority of them are impact-focused organizations. We are trying to figure out ways to help farmers reach the middle class.

With a couple of partners, the farmers contribute 50%. The organization contributes 50%. We get that cash upfront, but there's still a barter part of it. When we sell that crop, they do the barter loan back. Good Nature Agro gets the money upfront, because the partner is paying the extra 50% in cash at the beginning of the season.

The income from that barter loan goes into a revolving fund to help recruit more farmers in the future and ensure that they grow. I'm excited about it because it's a way to both get farmers to save into the middle-class, not take on more loans than they are able to, but reach more farmers.

In the other model, farmers contribute 50% and the partners contribute 50%, but that's rare.

Rhishi: There is some threshold that a farmer has to be above to participate in the program. The revolving fund is an interesting model because it can pull in people who are not at that threshold to come up to that threshold.

Kellan: We can work with the partner organization. They have a thousand farmers and they can only do 30%. We want to cover the rest and we are going to use our funds and the barter. The revolving fund to help make sure that they can participate. We cap the downside risk, which comes down to currency risk. Due to this the in-kind loans are key as they don't have to track the currency depreciation. It is a win for us and for the farmers.

Rhishi: It depends on who is the off-taker (off-taker is an entity which takes/buys the grain from the farmer) on the other side. If they are outside your country, then you are exposed to those risks.

Kellan: When we started Good Nature, the currency was quite strong. We didn’t think about it in year one. The currency took a big hit in year 2.

USD to Zambian Kwacha exchange rate for the last 10 years. Source: xe.com

We are increasing USD sales. We work with our off-takers and our seed customers to create contracts with spot prices in USD. We have been able to get over 80% of our sales in USD on the seed side. We are looking to get export sales, which make it a little easier to do USD and multi-year agreements.

We have been talking to a lot of local banks. Quacha loans that we could then match to the working capital structure. By keeping that as its own business line, try to battle depreciation. In real life, especially the USD sales, has helped protect our cash position, but on the financials, we take a big unrealized hit.

We are fortunate to have impact driven, collaborative, thoughtful, smart investors who have helped us address the currency risk in our business and figure out how to make the best structure to address it.

We have done all we can to help it not affect the business. We have done as much as we can to remove that risk from our farmers as much as possible too. So they are in lock step and partner with us to figure out how to make it work. We are a US parent company. The Zambian company is a wholly owned subsidiary. Our new Malawi company, which we are incorporating now will be a subsidiary. So having that US parent company helps protect our investors. Our debt investors invest directly into the Zambian company and our equity investors invest into the US.

Rhishi: Could you talk a little bit more about your breeding operation?

Kellan: We have a number or different partners for genetic material. It is a long process and a big investment. We have a staff of three, we have a breeding greenhouse and we are building a seed lab to be able to run our own testing in house. It is a multi-year year operation. We are adding a third component along with the greenhouses and the seed lab. It is our foundation farm, with land where we can propagate and grow the different seeds. There are dozens of varieties in any given year, and we use irrigation and other tools to make sure we get multiple seasons throughout the year. It is not different from any other seed company, except we multiply seeds with commercial farmers and smallholders. We are taking on this new model to do it with smallholders and prove that efficacy there.

Rhishi: The major crop (maize) might have a well established supply chain. What are the challenges with the legume supply chain?

Kellan: It's not necessarily less reliable because it's growing, it's smaller. In Zambia, the soy commodity industry is about 30% of the maize industry. So it plays second fiddle to getting access to macro or government services. If you look internally at our own supply chain, there is a lot of risk of working with smallholder farmers, both for quality as well as cost of last mile services. But that's been who we are since day one. We are working on the logistics to be out there in the field both for harvest as well as purchasing, and for training. We set up a large processing facility in Lusaka last year.

Two years ago, we made a big investment, almost half a million dollars in a brand new seed processing line. We can scale even for another couple of years. Now the big push is to scale our commodity processing units, but in Lusaka. So it's more centrally located for exports.

Rhishi: What are some of your expansion plans?

Kellan: Our expansion is around adding value in our key pillars; less around a geographical expansion, more offices and more farmers and a sheer focus on expansion of varieties. The expansion of geography is going to happen as we sell into more countries. Our export for off-take is increasing.

We are opening an office in Malawi. We are expanding to new parts of Zambia.

When it comes to varieties, we are looking to get our own varieties in the market for expansion. It's less about getting into cotton or sunflowers. So our investment in growth is in tech, but what does the tech do to support us? It's our processing capacity so that we can scale to reach the commodity numbers that we want to reach a seed as well. It is in breeding, R&D, and expanding our team.

How does Good Nature help women?

Rhishi: You said that the adoption of phones was 70% two years back. It goes down further in rural areas and is even lower for women. What are some of the struggles for women and their role in agriculture in Zambia?

Kellan: The context and the reality of women in farming is not only a Zambian issue but it is a worldwide issue. We have private extension agents (PEAs). We have one PEA for every 40 farmers. We make sure that 30 to 40% are women. It helps change the context where we are selling, celebrating women farmers, and bringing them into the fold.

We have started piloting household registration. For years, we had one farmer register knowing it is a full family affair to help keep a farm. We are starting to do more household registration to get the family into the system and to tailor our services.

A lot of our partner organizations have a gender lens. It's interesting because you'd think that we'd have more women farmers and more women through those networks. We are recruiting more women than some of these partner organizations. With one of our recent grants, we are bringing on a gender specialist who will be working with us for 18 months. We are excited to find and uncover what’s going on behind all those numbers.

Rhishi: That's fantastic! You mentioned that your investors are impact investors? What are their views on helping more women in Zambia through your program?

Kellan: It is less of a bottom line and more of an understanding of what our goals are. It is less that we are going to give you this investment and one of our KPIs is that 50% of the people that our money reaches are women. It's more of: What are you doing to reach the women population? How are you engaging women in leadership? Do we have women on our board, women in senior leadership, women in middle management at GNA?

We have 26% women on our staff, which includes senior field staff and business. With our PEAs we are 30-40% women, which is average for an organization, not amazing. We are making a concerted effort to recruit women.

Our investors are happy with that approach of continual monitoring, a continual investment in women, in leadership. So I cannot say enough how fortunate we are with the investors that we have. It's an incredible group of invested people and institutions.

Seed delivery: Photo provided by Kellan Hays

Rhishi: I always love to know what drives people.

Kellan: I remember being 17, a freshman in college and saying, if I'm going to work all these hours, I better be working on something important. I can't imagine getting up in the morning and doing something different. It is even cooler that it's what we created together. My team motivates me and I couldn't ask for better co-founders than Carl and Sunday.

You have to find the people around you, who can fill the gap, fuel you and your team and help you fulfill your strategy and your vision. Carl and Sunday are those people for me. We have an amazing relationship and they are a big reason that I wake up every day to do the work that I do.

So there are three people that I wanted to get their names out to you because I am so inspired by them.

Ndidi Okonkwo Nwuneli is the head of an organization called Sahel Consulting out of Nigeria. It's an agricultural consulting company that works with a lot of big players across the continent. Last year she started an organization called Nourishing Africa to get agri-food entrepreneurs across the country and to build networks. I love her work and she published a book a few weeks ago that I'm excited to read about.

Another woman I've been excited about lately is one named Tiffany Dufu. She wrote a book called “Dropping the Ball.” She's taken her priorities from being nouns to being action statements about what she wants to achieve.

When people say “What are your priorities in life?” You say “My family, my kids, my job, my career etc.” But that is not what gets you up in the morning and helps you check if you're working on your priorities or not. For her, it's about raising strong, black children - and that’s the action statement. That means that her children are her priority, but this is what she wants to accomplish. I love that concept because it helps me come back to say, “It's not my career, but what I want to accomplish as an actual impact that’s going to last longer than my hours of work”

Another person is Anushka Ratnayake, who's the CEO of MyAgro. She was doing agritech stuff around farmer savings, with scratch-off cards and mobile phones. It was a brand new way to think about farmers saving into the middle class vs. lending and borrowing scratch off cards. She has created the concept herself and is in four countries and reaching hundreds of thousands of farmers.

MyAgro and Good Nature are similar because of our roots in human-centered design. She's using human-centred design to build agro technologies.

Rhishi: Thank you very much, Kellan, for your time. Your work is inspiring and I want to wish you the best of luck!

Conversation Notes

Behind the scenes of Good Nature Agro’s Chipata office

Why we invested by from Finca Ventures

Meet the entrepreneurs: Carl Jensen and Sunday Silungwe, Good Nature Agro from MIT-D Lab