Megz Reynolds: A Learning Machine

This week’s conversation features Megz Reynolds. She is anything but conventional.

She started her career doing special effects in the film industry (Twilight saga). She transitioned from films to being a grain farmer in Saskatchewan. She has worked to bridge the gap between the farming industry and consumers. She has worked on mental health issues. She ran for office to advocate agriculture policy changes. She currently works in manufacturing, and is known for her “Manufacturing Monday” videos on Twitter.

I was most impressed by Megz’s learning process, her curiosity, can-do attitude, and the ability to engage in a conversation on any topic with anyone in the world.

I hope you enjoy the conversation.

One of many aspects of Megz’s personality!! (Image provided by Megz Reynolds)

From Films to Farming

Rhishi Pethe: Which parts of your film industry experience have translated to farming?

Megz Reynolds: In some ways they're similar industries. When you are creating a TV show or a movie, the focus is on getting that shot and prioritizing the production. It doesn't matter if you are pushing past a 12 or 18 hour day, or working through weekends, you do what you need to do to get the project done. It is similar to the busy seasons in farming, whether it's seeding, spraying or harvesting. You put everything else on the back burner. You focus on getting it done. So the need for a strong work ethic definitely translates.

The only thing I knew about grain farming before moving to the farm was that at some point everything breaks down. Working in special effects I learned to weld, to build things and basic mechanics. When I came to the farm, I started an apprenticeship as a heavy duty mechanic. I figured I should learn how to fix the equipment we were running on the farm. In an odd way, film gave me a pretty good leg up coming to the farming industry.

The one thing that film and life prior to farming did not prepare me for was the uncertainty that comes from not being able to control the weather or other factors that are needed to be successful. Three years into my farming adventure, we lost the majority of our entire crop to a 10 minute hailstorm at harvest. There was nothing in my life which prepared me for how that loss would feel. That experience is what got me into the mental health conversation.

Rhishi Pethe: I talked with Kim Keller (Do More Agriculture foundation) about mental health. She said there was a stigma around mental health. It has gone down recently.

Megz Reynolds: I agree with Kim, there has been progress made in decreasing the stigma that surrounds mental health. That said we are not anywhere near where we need to be. And not just in agriculture, but as a society.

In agriculture, the needle has moved. It is in a large part due to the “Do More Agriculture” foundation. And people within the industry opening up and sharing their stories. We've seen a transition with more support systems online, which helps. When you live in a rural area its hard to drive 1 or 2 hours during the busy season to see someone, having online support systems that can be accessed from the cab of a tractor is really beneficial.

When I first started sharing some of my mental health stories on social media, I was struggling and feeling like a failure. I had a lot of people reach out to me privately to have a conversation or to share their story. Now I see those people and many others opening up, feeling comfortable to put out a post knowing it could help somebody else. We've come a long way.

Connecting consumers and farmers

Rhishi Pethe: You spend a lot of time educating consumers about farming. What are some of the common misconceptions consumers like me have about farmers? What can the farming community do to address them?

Megz Reynolds: I don't want to create an us versus them mentality. I grew up in the city. I had a lot of misconceptions about how our food was grown or raised before becoming a farmer.

Coming to the farm, I approached it the way I approached everything else. Why are we doing this? Why does this work? I realized I had a unique lens of being a consumer, who came without understanding, and learned and became involved in the process.

“I want to be able to have a conversation with the person I used to be.” <Highlight this quote>

96% of farms are family owned and operated in Canada. Those not on a farm are three generations removed from the family farm which makes it hard to be connected. For our Great Grandparents it was easy to be connected to agriculture. Somebody in your family was farming. And so there wasn't a disconnect. Nowadays it's not intentional, but if you're not around it, how do you learn about it and why would you spend the time understanding what's going on?

I got on social media to talk about it.I wanted to share what I was learning in a non-threatening way and my girls were really helpful in that. I wanted to connect to other parents. Say look I am a parent too, I care about my kids and want to keep them safe, I also trust the food we are growing and feed it to my family.

Farming has changed dramatically with advances in technology, seed breeding, and equipment. And suddenly it's a foreign concept, it’s not the backyard garden and it's scary. We didn't realize while all these advances were coming online that we needed to be transparent and talking about what we were doing, and why. This really fuelled that disconnect and mistrust.

If you're a parent, the last thing you want to do is stand in a grocery store, scared of the food you're going to buy for your children. Powerful and successful anti-science movements and lobby groups have put fears out there. We need to have a conversation and share what we're doing and we need to do that in a respectful way.

Many producers have joined the conversation, which is great. However there is still a lot of negativity, when people don’t agree with each other. Those in agriculture trying to have the conversation need to be respectful and not confrontational, otherwise why would anyone seek out that dialog? It doesn't mean everybody always agrees, but at the end of the day, you gotta be nice. You can't be an ass.

Rhishi Pethe: How do you know the conversation is changing? Is it having an impact on how consumers understand what happens on the farm?

Megz Reynolds: It's hard. There's a lot of people having a conversation and not always getting past agriculture. Five years ago I started to focus more on policy. I felt policy was a space where I could have a positive influence.

At the end of the day, we all are connected and we need to remember that. It's easy in a developed nation to make a choice of organic, vrs conventional. If I have disposable income I get to choose to pay more for my choice.

But when you create a policy to dictate what tools producers can have, “We don't want GMOs because we're scared of them.”

You need to be aware that you are opening that door for similar policies to be created in developing nations. When you live in a developed country and you have choices, it's an easier push to make change based on your emotional belief structure without understanding how changing your country’s policy could be affecting producers in say Africa. They may not have a crop, feed their families if they don't have a GMO drought resistant corn variety.

Groups from all sides push to create policy and we as consumers vote with our dollar. We are influencing our policymakers. It is an important place to focus the conversation.

Policy, tools, and sustainability

Rhishi Pethe:The farm bill here in the US is always a huge undertaking. Last year in India, there were huge protests by farmers. What are some of the policy issues you are interested in working with the local, the state or the federal governments in Canada?

Megz Reynolds: For me, it's about having a science-based approach. I spoke on a regenerative ag panel a couple of days ago and that was my focus. When we negotiate trade deals, we do so from a science-based perspective. When we are talking about climate change, we're being asked to believe the science.

But oftentimes, when we get to agriculture, we run with emotions and not science. It's important to focus on science. And especially moving forward, agriculture is able to be part of the solution.

Producers need access to biotech, synthetic fertilizer, and chemical sprays. It doesn't mean they need to use them all the time or that having access to them means they won't push to improve their methods. The weather is changing. Producers need to have access to all the tools. In Europe, a lot of policies have been brought in by quote unquote green politicians, to push environmental change. They do not understand the whole process and do not communicate with producers..

I have a friend who is a pork producer in Germany. They brought in a regulation a couple of years ago to have lights on in your barn at night. Animal activists said, if I get up in the middle of night, I need a light to find food and water. All these pigs have to have lights on at night. It screws with their sleep cycles and their melatonin levels. But it's a human saying, if I need this, then pigs need it too.

Agrifood Standing Committee - Image provided by Megz Reynolds

Rhishi Pethe: There is a religious belief in tech that tech can solve all problems. You believe policy is the highest priority item. Is it because you believe policy can give the most leverage?

Megz Reynolds: We can't have access to the ag tech we want, or need without having the policy that supports it. CRISPR technology was used to create the COVID vaccine. But how will governments allow it to apply it to agriculture, which could have a huge benefit to how and what crops we grow.

We've got autonomy coming online. With current regulation, I can use autonomy in my field, but I can't do the “follow me” command to get it to the next field. The regulations do not support it being on the road by itself. It needs to be loaded onto a trailer. It creates more time and less efficiency in the whole system. Without advocacy on the policy side, and without a conversation, you don't get to use all the tools being created.

Rhishi Pethe: What are some of the top issues for governments to take a more science-based approach? Or is it more of a general principle?

Megz Reynolds: An example is front of pack labeling for sustainability practices. Quaker Oats has a report card. They only work with farms which score at a certain level. They've decided what regenerative agriculture is for them. It comes back to how we define it and who defines it. A science-based approach is to look at everything. We can have regenerative agriculture using pesticides. We can have regenerative agriculture using GMO seeds.

What does the end definition or certification mean? If it's a company creating a marketing scheme to drive consumers and policy, was it where we wanted it to go? I can go buy non-GMO bread and pay more for it. However there currently is no GMO wheat to make the non-GMO bread, so I have just spent more on a marketing scheme. It's not science-based, but driven by marketing and geared towards emotion. And emotion drives the dollars, the policy, the fear amongst consumers. How do we bring science into this?

One of the most important issues globally is access to biotech seed. Farmers all over the world are struggling because they can't have access to biotech. As countries allow biotech, how can we promote a science based approach so developing countries can adopt these products and in turn be able to feed their families, their communities, and create food security?

Rhishi Pethe: You have a lot of companies coming out and making declarations around regenerative or sustainable farming. Is it more aspirational or is it just marketing?

Megz Reynolds: You have to look into the company. What are they doing? I know McCain's is there. They've set their own company goals based on the Paris accord, and they're being audited. I think they are doing a good job of saying “We're committed to this and we're going to take it seriously.”

Some companies say “We are going to be net zero by this date.” They create their own set of standards and are never audited. Some people say regenerative agriculture is the same as organic. You cannot use chemicals or synthetic fertilizers or GMOs. McCain wants to focus on creating healthy soils.

Carbon markets and Agtech promise

Rhishi Pethe: There has been irrational exuberance on carbon markets. Three years back you were against a carbon tax. Have your views changed?

Megz Reynolds: I was vocal against the carbon tax when it was first rolled out. I have struggled with the way we had implemented it in Canada. When you look at grain agriculture, you're a price taker, not a price setter. When your costs of doing business go up, farmers can't pass the costs on.

Politicians didn’t say, “We're putting this additional tax on farmers and they can't pass it on. How is this sustainable for them? What can we do?”

I'm not a big fan of a “sin tax,” which is what it is. A majority of Canadians want it. I am fine with the tax, if it is used to create change. We're giving rebate checks to all Canadians, from the collected tax. To me that's a major flaw. Use the money to create grants for communities, industries, and tech companies to bid on the grant money to fuel their projects, to fuel their green revolution, to create noticeable and effective change.

From the Fortune Reinvent Event, 2018. Image provided by Megz Reynolds

Left to Right Beth Kowitt (Fortune), Amol Deshpande (CEO FBN), Megz Reynolds, Mark Young (ex-CTO of The Climate Corporation and current COO LandTrust Inc.)

Rhishi Pethe: You were doing no-till farming. Carbon markets have a principle of additionality. If you do something different, then we will incentivize you.

Megz Reynolds: We're not at a place where we can stick a probe in the soil, and it will tell you how much carbon you have sequestered. It's hard to go to an emitter and say, “We're going to sell you these credits, but we can't quantify it.“

It will depend on what you are growing, what your rotation is, where you are, what your weather systems are, what your yields are.

Having a carbon market can be an important piece to help farmers improve their farming practices.I see farmers selling credits, (when we can quantify them) as a way to help them economically transition their farming practises to those that will create healthier soil.

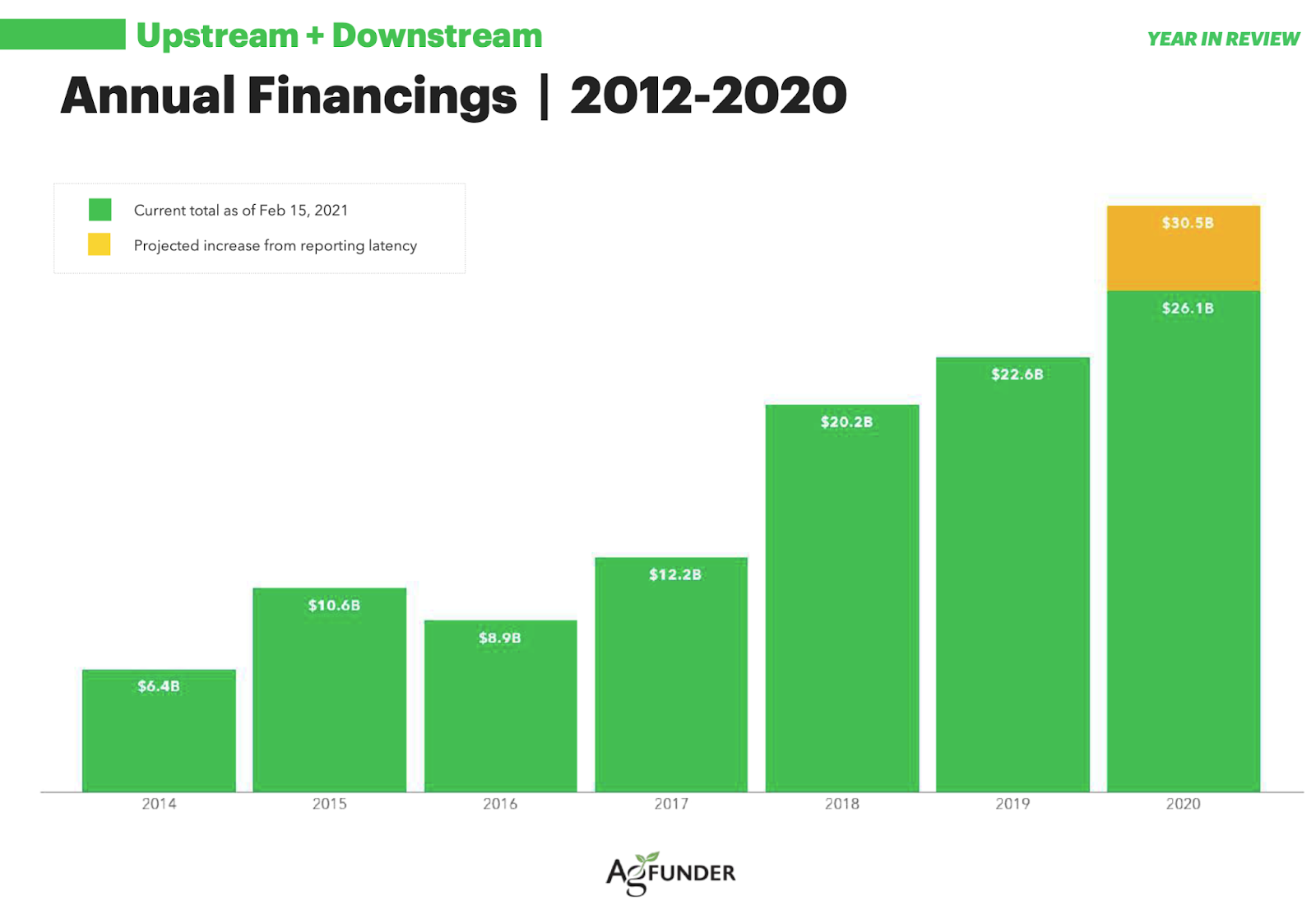

Rhishi Pethe: There is a lot of investment coming to AgTech. If you look at the last 10 years, do you think Agtech has lived up to its promise?

Megz Reynolds: I don't know if Agtech made a promise. For the first time, the tech is able to quantify what you are doing on the farm, track it, monitor it, and farmers can use and benefit from that information. We are not jotting things in a notebook. I no longer need to run down a field sticking flags in the soil and hope they are still there in fall when I try to figure out what we did.

From 2021 Agfunder Agrifoodtech Investment report

I wouldn't say ag tech has failed. It's that policy or lack of trust is failing agriculture by not allowing tech to be utilized in the way it could be.

Learning process and inspirations

Rhishi Pethe: If I look at your trajectory, you were in films, became a grain farmer, are an equipment person, taught mental health, consumer advocacy, ran for office. Each of these itself could be a career for someone. I'm curious to know about your learning process.

Megz Reynolds: I need to be learning. I could easily spend the rest of my life in a classroom. I always want to understand the bigger picture. How does everything connect together? That's why I've reinvented myself so many times. I need new challenges.

For me, it’s reading, it’s podcasts, it’s hands-on work, it’s conversations. Once I get into a new industry, I want to have conversations with people in the industry and not necessarily with people who align with my viewpoints. I want my views and beliefs challenged, in a mutual respectful conversation.

If I find something interesting, I will share it. I did that with farming and now again with manufacturing with my manufacturing monday videos. We think about the automotive manufacturing in Ontario, but we don’t think about equipment manufacturing and agriculture. Living and farming in Saskatchewan, with almost half of the agricultural acres in Canada, I didn’t know about the equipment manufacturing here prior to getting involved in the industry.

Rhishi Pethe: I want to dig into the tactics of learning. You read, listen to podcasts, talk to people. Could you tell a story about what you did to get into a new area as quickly as possible?

Megz Reynolds: When I first came to the farm, I apprenticed as a heavy duty mechanic. I learnt about how the equipment worked. As a farmer, I would run equipment in the field, know its limitations, pick some design flaws or say “Why did you do this when you could have done this?”

I learn by doing. I found an old house a couple of years ago. I needed a basement for it. I said, “Let's build a basement.” My dad said, “You can't build a basement, as you don’t know how to build a basement.” “Well, it's fine. I'll figure it out.” It’s the mentality I bring to everything I do. I don't see not knowing about something as a barrier. It's one more thing to learn about or accomplish.

Now, I work with a company which makes the parts which go into the equipment I used to work on and run. I'm in sales, but I spend time on the floor. If it is busy, and help is needed on the floor, I'll put on my coveralls and work on the floor. It's a different way of using your brain. You need to switch gears. Here are different pieces of equipment to bend wire. How do I need to set them up? What do I need to do to create these bands or loops? I find it fascinating and want to understand it.

https://twitter.com/farmermegzz/status/1394410164867014658?s=20

Rhishi Pethe: You recently read books like “White fragility” and “Stand from the Beginning.” How do you reflect on them based on your experiences?

Megz Reynolds: I believe it is our responsibility to always be learning, especially about things that have never personally affected you, how else do we create systemic change? “White Fragility'' was hard for me. It highlighted things I've done without making a conscious choice. It's what was indoctrinated into me, how I was raised to see the world by the systems in place to keep things status quo.

I believe in white privilege, I understand I have it. It's been frustrating to try to have a conversation on social media with all the people I am connected with after running for office in a rural area.People are threatened by those books. The denial and anger in their response highlights how we still have such a long way to go. The books opened my eyes to some things, but it doesn't mean I don't still have a long way to go. When it comes to racism, Canada has a big history too.

I talk to my girls about what I learn or observe in a way that works for their ages. We read children's books about racism and we talk about the trauma that exists and how that continues to affect so many people. We need to talk about it and we need to understand what happened and what is still happening.

Megz with her family, Image provided by Megz Reynold

Rhishi Pethe: I've been impressed with your learning journey. I'm curious to know the people or the situations which inspire you.

Megz Reynolds: I'm inspired by people who put themselves out there, take on new challenges, break barriers, break glass ceilings. A big driver for me is my kids. I want them to know they can do anything and go after anything they set their mind to, not because I tell them they can but because I have modelled that for them. I'm lucky to have close friends who hold me accountable. If I do something out of line, or if I write something which isn't my best, they'll say, “Hey, Megz, you can do better.” It is important to surround yourself with people pushing for more, people who are constantly learning, building their base and who are using that growth to bring others up.

Rhishi Pethe: Thank you for your time Megz!