Open source software (continued)

Part 2 of OSS in ag

Analysis

💡Key takeaway: Open source technologies can democratize access at potentially lower costs, but does agriculture have the numbers to support a thriving open source system?

Last week, I wrote about open source software in agriculture by using the examples of AgOpenGPS, OWL, OpenAg, and OADA. Based on some interesting feedback received from many readers, I am going to delve into the topic of open source software within agriculture again this week.

As I said last week, I am quite excited about the power of open source, and community building. Let us delve into some of the principles of open source software and licensing, as contrary to what we would like to believe, everything is not rainbows and sunshine with open source.

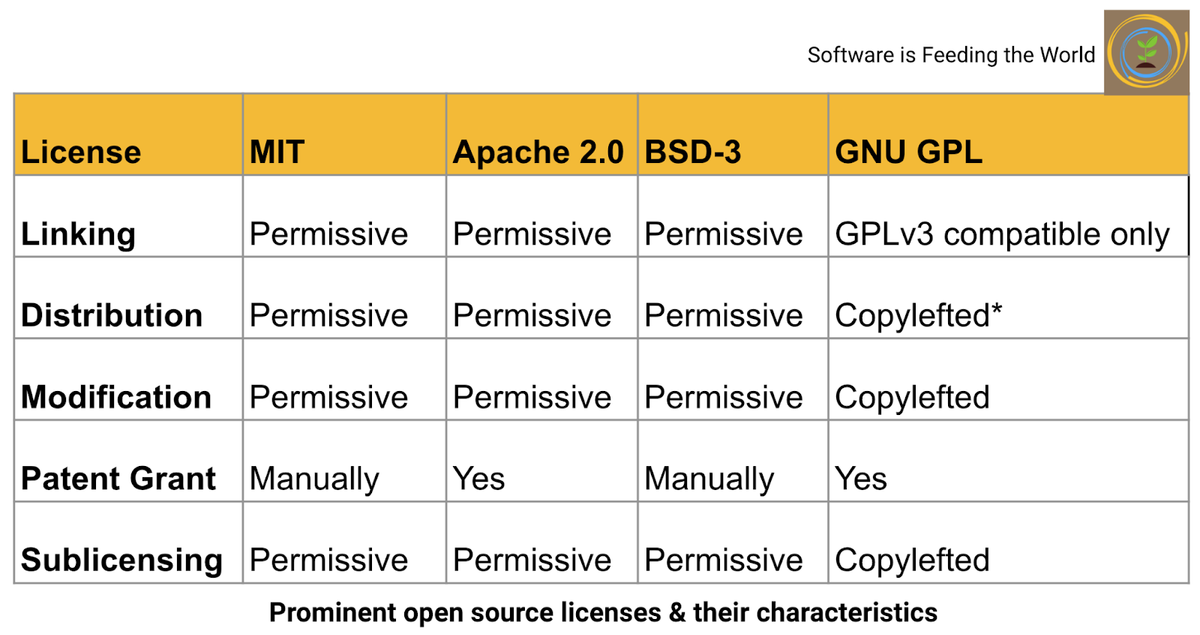

Principles of open source licensing

Linking - linking of the licensed code with code licensed under a different licence (e.g. when the code is provided as a library)

Distribution - distribution of the code to third parties

Modification - modification of the code by a licensee

Patent grant - protection of licensees from patent claims made by code contributors regarding their contribution, and protection of contributors from patent claims made by licensees

Sublicensing - whether modified code may be licensed under a different licence (for example a copyright) or must retain the same licence under which it was provided

Every open source software will come with a license and depending on the type of license, it will have different characteristics when it comes to the principles of open source.

*Copylefted: Both copyleft and permissive licenses allow developers to copy, modify, and redistribute code (derivative or otherwise) freely. The most important difference between the two, however, lies in how each approaches copyright privileges. Permissive licenses allow developers to include their own copyright statements. Copyleft license rules require all derivative works be subject to the original license.

Any engineering team which wants to use open source software or modify it, should have a clear understanding of the open source software license terms, how they plan to use it, and how they plan to monetize it..

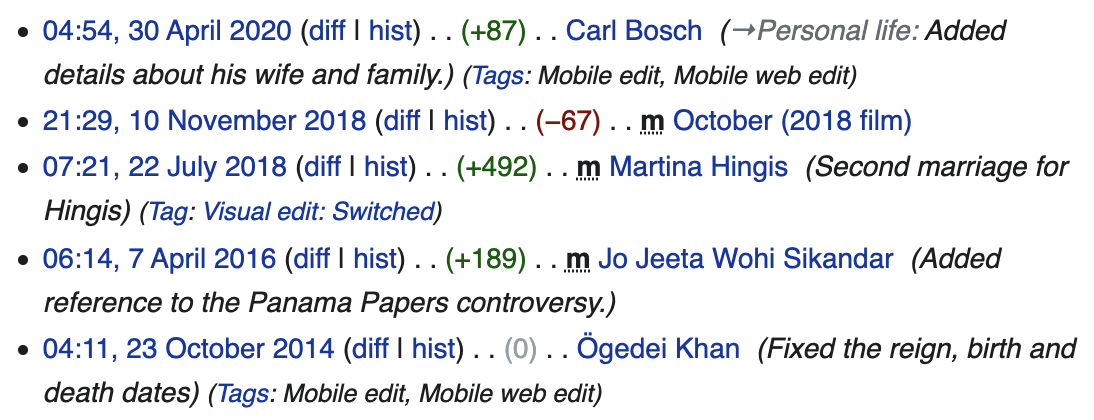

Another challenge with open source is the size of the open source community, and any monetization opportunities available to the community members. Most of the open source software falls in the category of tools, rather than applications. A tool by definition, can be used to build more interesting applications, and so a tool has wider usage compared to an application.

Some prominent examples of open source software supported by a large community of developers are Linux, Mozilla Firefox, etc. Other open source software, developed by large tech giants, but then open sourced to a large community of developers includes tools and operating systems like TensorFlow (ML tools from Google), PyTorch (ML tools from Facebook), and Android (mobile operating system from Google, with many variations). If the open source tool provides monetization opportunities to developers (and enterprises), then the ecosystem can include a large set of developers and users.

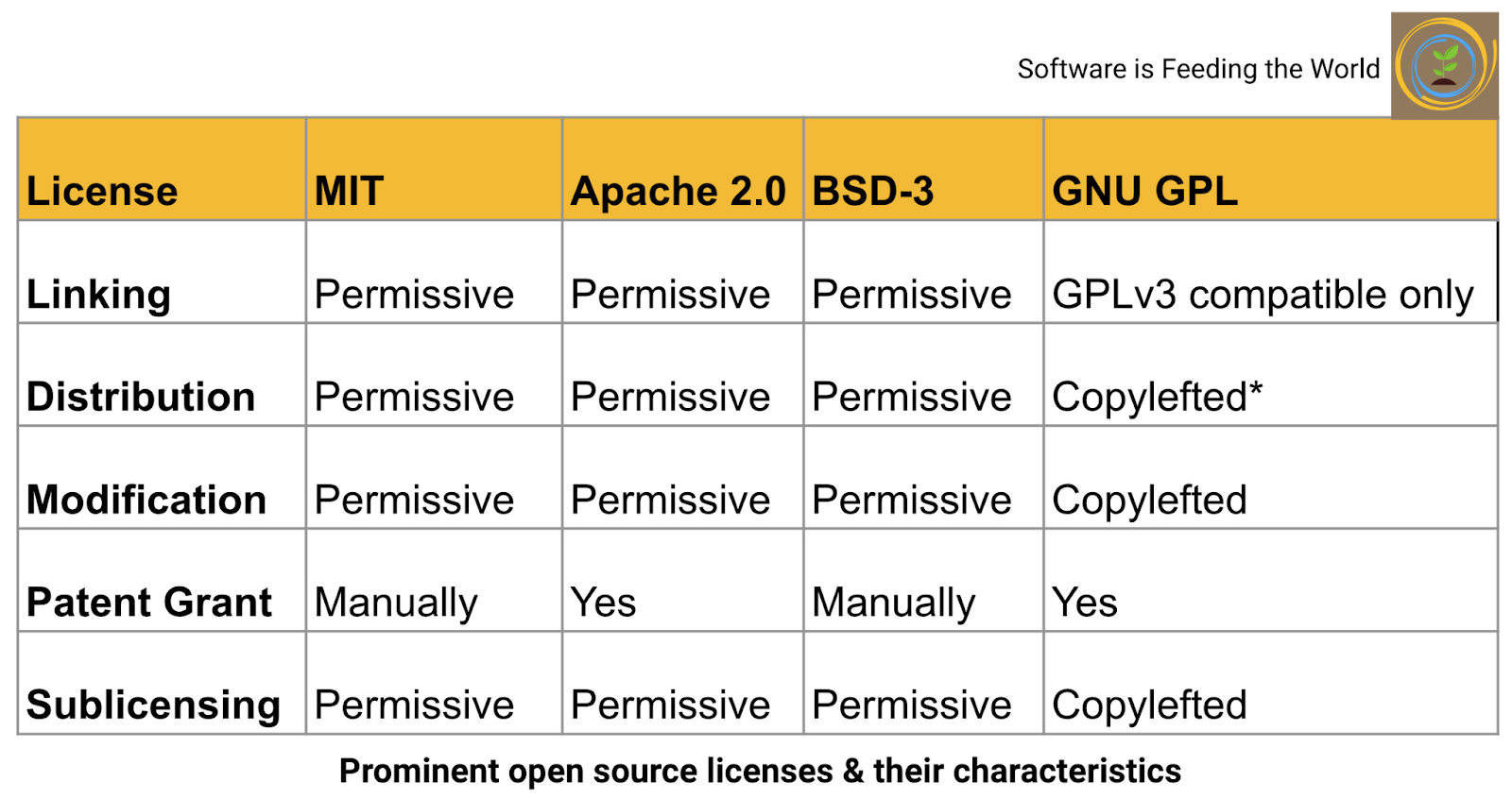

A counterexample is Wikipedia, where a very small section of editors update the open source website, as there are not many sustainable monetization opportunities for Wikipedia. In fact, only 0.3% of the total Wikipedia users have updated an entry in the last 30 days. Yours truly falls in the longest part of the long tail, as I have made a total of only 5 Wikipedia updates

Lifetime Wikipedia contributions for user rpethe (Rhishi Pethe)

For an open source software (or content like Wikipedia) to continue to add value on an ongoing basis, it needs a large enough community of developers and users, and if those developers and users can monetize some of their contributors, then even better.

Another important characteristic is that it is relatively easy and inexpensive for a large number of users to acquire the tools necessary to the open source project. An open source project can thrive if the skills necessary for contributing to it have high leverage, and can be used to earn some money. For example, software engineering.

During the podcast with Tim Hammerich, the original developer for AgOpenGPS talked about how it is relatively inexpensive it is to get a Raspberry Pi, an Arduino unit, and watch YouTube videos for free to hack together a system to provide you with auto-steer and other GPS capabilities.

Any open source ag software will potentially have a fewer number of developers compared to a more generic tool or application. Similarly open sourcing a tool can have higher value, and potentially more traction, as developers and users can use the tool to build an application that works for them.

For example, Digital Green provides an open source set of tools called Farmstack. Farmstack is a set of prebuilt and custom connectors for connecting different databases, data warehouses, and different data file types.

Digital Green is a global development organization that empowers smallholder farmers to lift themselves out of poverty by harnessing the collective power of technology and grassroots-level partnerships.

Given that Digital Green specifically targets smallholder farmers, the number of potential users will increase as more smallholder farmers become tech savvy, and have access to data, as reflected in Digital Green’s value prop.

When farming families have access to information about their soil’s health, availability of inputs, weather forecast and potential pest attack together with scientifically vetted, localised, timely advisories, they stand a chance to boost agricultural productivity.

Farmstack is a tool, rather than an application, and so it can be quite useful to connect different data sources, and try to drive value from those connections.

Digital Green has a mission driven, technology forward, and motivated team. I am personally a big fan of Digital Green, and their model to help smallholder farmers.

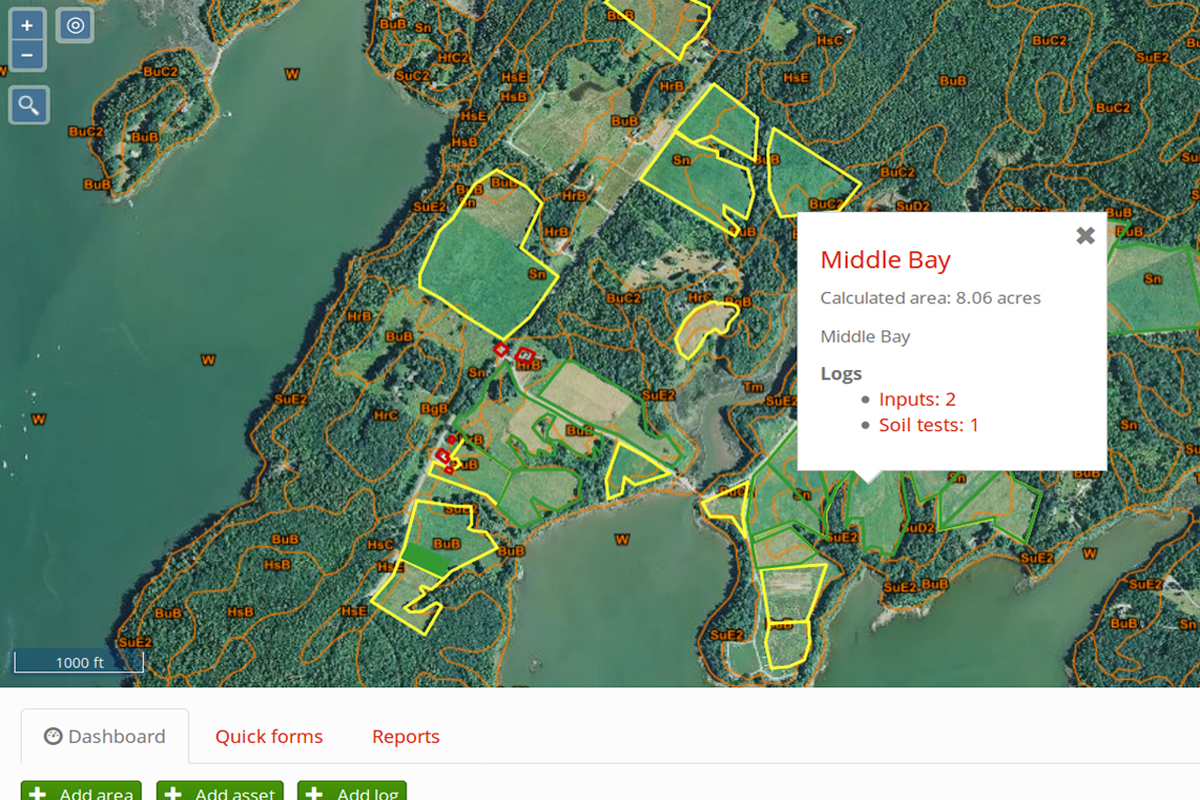

FarmOS and OWL are open source applications that might have to be customized for different use cases. Based on the description of farmOS, it can be used as a tool for data collection, though there will be differences in how different groups of farmers manage their records, plan, and keep records.

farmOS is a web-based application for farm management, planning, and record keeping. It is developed by a community of farmers, developers, researchers, and organizations with the aim of providing a standard platform for agricultural data collection and management.

The farmOS server is modular, extensible, and secure. The farmOS Field Kit app provides offline data entry in a native Android/iOS app. farmOS will be an interesting tool for small entrepreneurs, who want to customize and provide an application to a certain set of farmers.

farmOS has a lot of promise due to its extensibility and can be used to address additional use cases like tracking animal movement, connection with soil moisture sensors, greenhouse humidity by utilizing off-the shelf inexpensive tools like a Raspberry Pi.

Farmier satellite view.

Given the small number of users in agriculture in the developed world (for example, there are less than half a million row crop farmers in the US), and the challenges with technology access for smallholders, I am a bit skeptical about broad adoption of open source tools within agriculture, though tools like Farmstack from Digital Green hold promise.

Technology trends

Sustainability practices badge

💡Key takeaway: Certification (badging) of growers through a grain-trading platform will reduce transaction and search cost for grain buyers, while offering more optionality for growers

Bayer recently announced the availability of sustainability information on the Grão Direto’s grain trading platform. A sustainability practices badge is awarded to farmers who score high on sustainable farming practices surveys. The survey assigns a score to practices like no-till, reduce use of nitrogen, soil management, or crop rotation.

"Sustainability Practices Badge“ indicates which farmers on the platform are utilizing agronomic practices that are more beneficial to the environment.

Grão Direto gathers, processes, and displays ESG data from different sources. The grain marketplace provides additional visibility into farming practices, and the information can be used by buyers to inform grain transactions. It is a novel way to provide visibility to buyers. Sellers are scored based on a survey. It does seem different from an MRV process (Measurement, Reporting, Verification) for carbon in three ways.

- It is based on self-reporting

- It is focused on practices, and not outcomes

- ESG includes elements of social and governance, and the current Grão Direto approach is about potential environmental and agronomic outcomes. I am sure they are working on adding S & G information to the platform.

Grão Direto pulls farm gate information to the grain trading platform, and makes it available for smaller buyers, rather than just larger buyers, who might have their own ESG initiatives.

A grain trading platform will work if there are information asymmetries between buyers and sellers, and if the buyer and/or seller side is fragmented, and not dominated by big players. This was a challenge faced by grain marketplaces in the US. Grão Direto in partnership with Bayer is focusing on additional value adds like analysis, sustainability badges, bringing additional growers on to the platform, and an easier workflow for growers. The “sustainability practices badge” is defined by Grão Direto, and it is not a regulated badge. It does not stop another entity to come up with their own version of the badge, and could potentially cause some confusion. (Imagine you go to the grocery store, and depending on which brand of “organic” milk you buy, it has a different meaning) If a majority of the transactions in Brazil go through the Grão Direto platform, then it becomes the defacto standard and less of an issue.

Beyond “hot dog-not hot dog”?

Based on publicly available information, Greeneye technology, which provides see and spray systems, can detect 95.7% of weeds in multiple green-on-green situations from all spraying applications.

The Greeneye system controlled 95% of weeds in company trials, slightly below the broadcast efficacy rate of 97%. For the same chemistry application with an efficacy similar to broadcast spraying, the system achieved an average herbicide savings rate of 78.45%. The precision spraying system is supposed to be able to travel at the same speed as broadcast spraying at 20 kmph (12 mph), to ensure that there is no reduction in productivity for farmers.

The pricing and go-to-market for the system has not been revealed, though Greeneye has indicated an ROI from 6 to 18 months. The Iowa State University’s extension and outreach program published estimated production costs for corn, soybean, alfalfa, etc. in January 2021 for the 2021 season. Input costs have risen significantly since. Estimated herbicide costs were in the $ 40 to $ 50 range on a per acre basis.

If the average herbicide saving is 78%, it would be a saving of $ 31 to $ 38 per acre per year. For most technology products a rule of thumb is that you can charge about 10-15% of cost savings, and about 25-33% of new revenue generation. It indicates that farmers might be willing to pay up to $ 3 to $ 4 per acre, if the pricing is on a per acre basis. This calculation does not account for the cost of hardware, support, and service, and the go-to-market strategy for the technology.

It does present opportunities to do a few additional innovations.

- Newer herbicide products with a different mode and intensity of action.

- Newer pricing models - also called outcome based pricing models, which promise an outcome in terms of weed protection, rather than selling products by volume.

The Goldilock farmer for Traive

Brazilian fintech company Traive has raised $ 17 m in Series A funding. Traive is led by a strong management team and was co-founded by the husband and wife pair of Fabricio and Aline Pezente, along with a few other folks. Traive has built a set of tools for ag supply chain businesses to access financial products and services and provide farmers with working capital loans. Traive’s solution provides a one stop shop for credit management for farmers, and their algorithms provide a real-time risk assessment.

Traive has spent a significant amount of time to really understand which customers are best suited to serve and how. Traive’s ideal customer are farmers whose needs are much more than a microfinance solution, but much less than what is supported by traditional banks.

The Traive solution digitizes the entire journey and provides a host of tools to input suppliers and manufacturers, including the following process steps

- Cash Flow management

- Smart loan application

- Doc search and management automation

- Credit risk analysis

- Credit policy

- Collateral digital

- Receivables origination

- Dynamic monitoring

- Portfolio Management

Currently Traive supports lenders, but will extend the product to the farmer for effective and near-real time communication with lenders during in-season and off-seaon periods.