Technology is people

Technology is only as good as the people running it

Germany had been defeated in 1945. American scientists were looking to seize technological secrets and combed through German industrial labs. They realized two things. One, Germany was not too far ahead of the US. Two, even though they shipped vast amounts of data and process documents back to the US, they were mostly US. Knowledge and expertise could not be written down to be transported, when the people who worked on it were not there. They quickly realized that technology is nothing without the people with the right skills, and experience.

Technology is people.

When John Deere recently announced their first fully autonomous tractor at the Consumer Electronic Show, they were making a similar point. (We will come to the actual tech in a minute)

To push the technology envelope requires a different set of skills, and experiences. You have to get some of the brightest, smartest, and ambitious people to come work for you. You have to motivate them with a sense of mission, and the challenge to work on hard problems.

Thomas Friedman wrote “The World is Flat” back in 2005. The world has been flattening along different dimensions for the past 50 years. CoViD has accelerated the flattening, especially for access to talent. Many tech companies are now allowing a portion of their employees to work remotely full time or part time, with flexible work schedules. How can a company based in France, or the Midwest, attract world class talent from Argentina, India, Vietnam, and small town Nebraska? This is especially true in agriculture. Even though some agriculture brands are very strong, they are strong in a very small section of the population (especially in the developed world).

Deere is playing a long game for talent as they show up at consumer shows, not just agri-equipment shows. They create slick marketing materials, and talk about tough problems around self driving, autonomy, and a mission to feed the world efficiently. The approach is different compared to other big brands in different parts of the agriculture and food value chain.

So what is really happening with this Deere announcement?

The “unbundling” continues

In edition 69, (The Unbundling of Humans (in Agriculture)), I wrote,

Throughout history, we have found human tasks and outsourced them to machines, and now more and more to algorithms and models. For example, a combine automates many tasks, makes harvesting easier, safer, and more efficient. We continue to unbundle physical and rote mental tasks so that we can focus on higher-order bits requiring creativity and imagination.

What’s the tech?

Let us briefly come to the tech and the business model. At its core, technology is like democracy. Technology is by the people, and for the people.

One of the key goals of technology is to reduce friction in your normal operations. (Less friction is a key part of a great user experience). If you scrolled on #AgTwitter right after the Deere announcement, you got a mixed message of many farmers saying they love to ride, many skeptics on whether the technology will work or not, and a long tail of farmers/operators talking about how it could make their life a little bit easier.

Autonomy addresses the friction of finding people to operate the tractors, especially in the developed world, where only 1% of the population is involved in farming. Workers are in short supply, and many young people might be moving to cities.

Autonomy addresses the friction of driver fatigue, and time away from family. WIth climate change, as some of the operational windows are shortening, autonomy will be a good way to increase the chances of hitting those narrow windows.

Deere is calling the new equipment fully autonomous. In edition 69, “The Unbundling of Humans (in agriculture”, I wrote,

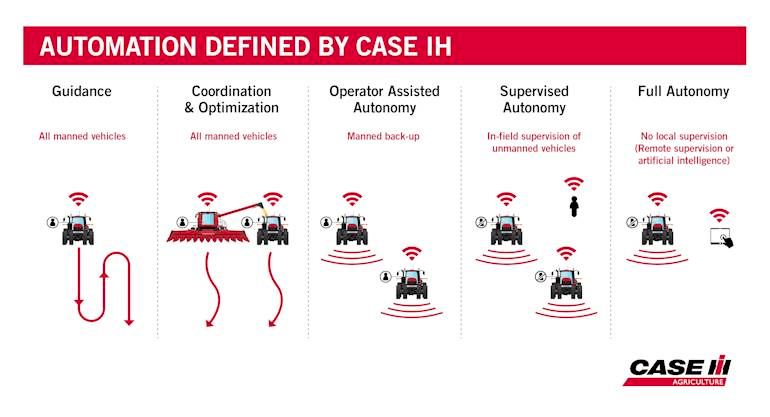

Within agriculture, most of the talk around autonomy and automation has been around the unbundling of physical tasks. Based on the definition of autonomy from Cash IH, we are already on our path towards full autonomy. The different levels of autonomy are still heavily focused on unbundling the equipment operator and some of the human infrastructure that goes with it.

In an ideal situation, 8R operates with full autonomy (level 5), but depending on the situation it might fall to level 3 (operator assisted autonomy) or level 4 (supervised autonomy).

The new autonomy package includes 6 pairs of stereo cameras to enable 360-degree obstacle detection and calculation of distance. A stereo camera includes two or more lenses with a separate image sensor or film frame for each lens.

The images from the stereo cameras are processed in real time (no details on the processor, but my guess is that they are using specialized chips optimized for edge computing) to determine if the machine continues to move or stop. The report indicates that the machine learning models will classify each pixel (or image) in approximately 100 milliseconds. If the tractor is moving at 6 mph (approximately 10 km / h), it will move about 28 cm (11 to 12 inches) in 100 milliseconds. It will have a braking distance in the 10-20 ft range, depending on a variety of factors.

If the equipment has sideways looking cameras, it will have enough time to look for obstacles upto 45 to 90 feet away, and make decisions on movement. The machine learning algorithms (using a neural network approach) will be able to differentiate between “weeds” and “crops” on the fly. It is not clear if the same configuration will be used for their see & spray product. See and spray has stringent requirements for performance. The spray has to accurately hit the target, while the equipment is moving. Sprayers typically move faster than other agriculture equipment, and so there is even less time for the machine learning algorithm to process images, and make decisions. The Deere system does not mention LiDAR (as pointed out by Todd Janzen of Janzen law). LiDAR is typically more expensive than cameras, but it can work in a larger variety of weather conditions.

One of the key challenges in using vision based systems in self driving vehicles, is the presence of false positives like shadows, different lighting conditions at different times of the day and night, cloud cover, and wind blowing leaves in the path of the tractor. The stereo cameras will help alleviate some of the problems, but Deere plans to operate the autonomous equipment by keeping the lights always on. The always on lights will provide more consistency to the captured images, reduce the number of false positives, and make the machine learning algorithm more robust.

What’s the go-to-market and user experience?

Deere will initially rent out tractors with the autonomous equipment already added. Later on, Deere will let farmers bring their own tractors to be retrofitted with the autonomous technology. It plans to support at least the past three years of tractors and may eventually support older machines. Deere will use its extensive dealer network to help with retrofitting, and will provide technical service. Depending on the ease and cost of retrofitting, Deere might decide to offer a usage based or subscription model to get a faster ramp up on adoption.

John Deere says that technicians at its dealerships will be able to fix complicated problems with the autonomous systems. Farmers will be able to make some repairs on their own, like wiring the harnesses holding the pods to the tractor or fixing the brackets that hold the sensors.

The interesting aspect of the offering will be the need for a centralized remote network operations center, to support a set of customers. The operations center could be anywhere in the world - Vietnam, Estonia, Philippines, India, or Peoria. It will include people who can respond to alerts and stoppages in the field, and make real time decisions to continue the operation of equipment or pass the information to the farm operator/farmer to make a decision. Will it change the relationship between farmers and their dealers, due to some disintermediation of the grower-dealer relationship, when it comes to autonomous equipment operations?

It will pose some interesting challenges in terms of liability and user experience. What happens when the machine learning model stops the tractor, the remote operations center decides to continue the operation, and it results in some equipment damage or worse a serious injury or death?

Will the operations center decide to wake up the farmer in the middle of night, because the tractor was stopped and requires on-the-ground and in-field manual intervention? What happens when the number of manual interventions required is so high, that autonomy becomes a nuisance? (For example, in episode 152 of Seinfeld, Jerry’s carpenter Conrad asks Jerry for every little decision, and so beats the purpose of Jerry outsourcing the work to Conrad!)

In an ideal situation, the autonomous equipment will do all the work, and will not have to stop or any interruptions to the operation of the autonomous equipment will be handled by the operations center. How can a system like this reduce the number of stoppages?

One interesting idea will be to go and scout the field using an autonomous drone and identify potential obstacles on the field (for example, rocks, water bodies, weird slopes, areas where the farmer does not want to farm etc.). Rock picking robot company TerraClear uses a similar approach. A drone flight goes and identifies the location of rocks, and then it is fed to the TerraClear tractor to go and pick the rocks.

The information from the drone, combined with information from previous passes on the same field by other equipment can be used to do path planning. The path planning algorithm can identify the optimal path for the tractor to traverse, and can optimize on a variety of dimensions, including obstacle avoidance. For example, Canadian agtech company Verge, explicitly focuses on “simplifying farm planning to reduce in-field decision making.” This additional intelligence in combination with real time decision making by Deere’s autonomous equipment can reduce the number of manual interventions required, reduce friction, and make the autonomous equipment really autonomous.

This is a good thing for smaller robotics startups. Acquisition or M&A, were always the more viable exit options for robotics and autonomy startups. Deere’s push into autonomy makes it more real in the overall market, given Deere’s unique and extremely strong brand position. If your robotic startup has some unique technology, you will become more of a target for acquisition by OEMs, large retailers, etc. Deere has made acquisitions in the space (Blue River, Bear Flag), and so has other OEMS like CNH (Raven).

From a farming standpoint, autonomous equipment will change what it means to farm in the future.

In edition 52, I interviewed Mark Young, ex-CTO of the The Climate Corporation

The notion of what it means to be in ag will change over time. You could be a “farmer” and work in a warehouse. Even in broad acre production it'll change because as autonomous equipment and automation takes over, what it means to be a farmer will change.

If more and more farmers adopt autonomous equipment, will it lead to larger equipment and larger operations or will it lead to smaller equipment, as the equipment can now operate for longer times? For example, Agtech startup Sabanto has been experimenting with small autonomous tractors for a while. How will farmers who own and operate the land react differently compared to farmers who rent land from a landowner in Chicago or New York?

In edition 52, I interviewed Mark Young, ex-CTO of the The Climate Corporation

Why do we have millions of dollars of equipment sitting in sheds for 10 months of the year? It is almost ludicrous. I understand how it all came to be that way. But it is ripe for innovation. Autonomous equipment can do what we do today with big hardware, for one quarter of the cost. A lot of times when you have these big technology shifts, they cost a little bit more than the status quo because they don't have economies of scale yet.

Et tu Tillage?

Deere is starting autonomy from tillage. In principle, tillage is a less time sensitive operation than planting or harvest. There is a slight dissonance between the talk of sustainability from Deere (though to be fair to them, most of Deere’s sustainability goals are within their supply chain) and the push for more no-till operations for sustainable outcomes.

Beyond tillage, John Deere will look at other tasks carried out by tractors, like spring tillage and cultivating. And in the future, John Deere plans to extend autonomy to essentially every task a machine performs on a farm, from planting to harvesting.

Technology trends

Many people have done 2022 predictions and trends to watch for food/agtech. I don’t want to spend time on predictions, even though they are a fun exercise, but rather want to give you a sense of the topics I will discuss quite a bit in the coming year.

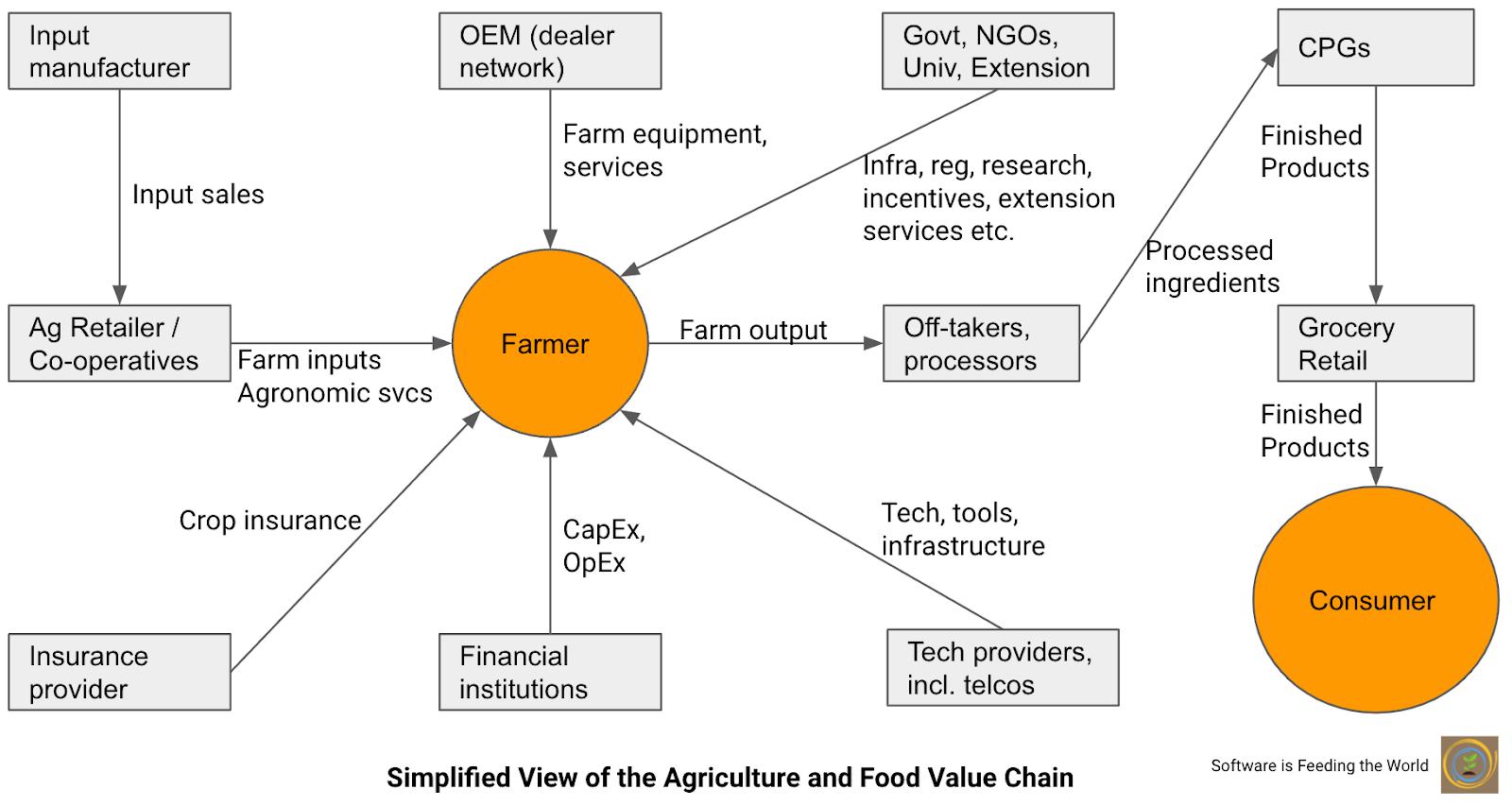

Full value chain/supply chain

Consumer demand, and what happens downstream from the farm has a huge impact on what happens on the farm. I want to explore different supply chain and logistics issues downstream, and its impact throughout the value chain.

Climate change, and sustainability

Climate resilience, carbon markets, water quality, GHG, regenerative agriculture, sustainable practices, will continue to occupy my attention in 2022 and beyond. I hope to explore the science, the economics, and business model issues associated with these topics.

Automation & robotics

As I discussed earlier, applications of automation, robotics, sensors etc. are expected to grow significantly over the coming years. Automation and robotics have the potential to cause some significant changes and I will continue to explore them.

ML/AI

From a personal standpoint, machine learning, artificial intelligence, data, and platforms are areas I have spent the most time with. I will explore ecosystem challenges, collaborations, different farming contexts, and business models through the lens of ML/AI, data, and analtics.

Water issues

I strongly believe access to clean, and sufficient water will be one of the most challenging and defining issues of the 21st century. My very first newsletter edition was about water and issues of use of water in growing rice in India. I will definitely explore

Smallholder farming

I briefly started exploring smallholder farming in the developing world with conversations with folks like Venky Ramachandran, Jehiel Oliver, Kellan Hays, and Eli Pollak. Agriculture and food systems in the developed world are fairly efficient, and most of the improvements are on the margins. The potential improvements in the developing world are massive, and I want to explore different issues related to food and agriculture systems in the developing world. Having grown up in India, it is also an area of personal interest for me.