Ag Economics and Solar flares with the Space Plowboy

SFTW Convo with Dr. Terry Griffin, Kansas State University

Every year I make a trip with family to Kansas State University to catch a college football game. I am in Manhattan, KS this weekend, and so I thought it would be appropriate to publish this SFTW Convo with Dr. Terry Griffin of Kansas State University. I had the opportunity to meet Dr. Griffin in person at his office. I have some pictures from my trip at the bottom of this email.

Dr. Terry Griffin is an agriculture economics professor at The Kansas State University. His specialties include cropping systems economics, precision agriculture, and spatial econometrics. Dr. Griffin was recently appointed to the Space Weather Advisory Group at the White House.

Dr. Griffin is a prolific writer and researcher, including somewhat geeky topics like impact of solar flares on farm economics. One of his papers is titled “Impact of the Gannon Storm on Corn Production Across the Midwestern USA” (Gannon Storm was the name assigned to the major solar storm the week of 10 May 2024. Solar storms typically occur every 11 years.)

Given I did my graduate program at Kansas State, I was very excited to talk with someone from my alma mater, especially someone like Dr. Griffin. Dr. Griffin is a systems thinker, who goes beyond dollars and cents, and thinks about the impact of decisions on the human condition.

Summary of the Conversation

Dr. Griffin and I discuss the multifaceted world of agricultural economics, exploring the importance of understanding agricultural economics as a distinct field. We focused on the role of technology in agriculture, generational perspectives on technology adoption, and the impact of automation on labor. The conversation also addresses the implications of GPS outages, the importance of cybersecurity in agriculture, and the future of AI in the sector, including a discussion on data ownership and its value.

Agriculture economics

Rhishi: What is agricultural economics? Why do we need to study it separately from other branches of economics?

Terry Griffin: A lot of universities offer an applied economics program instead of a strictly agricultural economics program because ag economics has evolved to include areas like health economics, rural development, and international programs.

I focus on the farm side, specifically farm management, which falls under microeconomics. But we also care deeply about macroeconomics within agricultural economics. What makes it distinct is that we think of it as applied economics. It’s not purely theoretical. We like to apply what we study to real-world topics.

For example, it’s not just about dollars and cents. I look at systems and I try to optimize those systems to function as efficiently as possible.

In agricultural economics, I study farm models. I try to optimize returns to land, labor, capital, and management, within the fixed costs and limited resources of the operation. So again, it’s not just about adding and subtracting.

We care a lot about utility, which means satisfaction or happiness. On a farm, it’s not just a business, there’s usually a rural household tied to it. That household includes a spouse, children, or other family members. When we analyze the system, we aim to maximize the joint utility of everyone in that household under a budget constraint.

It’s similar to what happens when a family goes to the grocery store. Let’s say they have $1,000 to spend for the week or month, depending on the family size. Their goal is to get the best mix of food that brings the most satisfaction to everyone involved. That’s optimizing within a shared utility.

Farm families operate the same way. When I look at a farm, I don’t just see a profit-maximizing business. I see a family trying to improve the overall quality of life for everyone in the household. And that’s a big part of what agricultural economics is all about.

Rhishi: When we talk about AgTech, most of the conversation revolves around ROI. People ask, Will it reduce chemical use? Will it save on labor costs? But what you’re talking about goes beyond that, and yet, it rarely enters the conversation. Why do you think that is?

Terry Griffin: As researchers, we’ve always acknowledged the importance of human capital costs. For example, making use of new technology, like site-specific yield monitor data or detailed soil data, offers a lot of opportunity, but it also demands a higher skill set.

To work effectively with that kind of data, you need to be more than just a farmer, you need to be an analyst. You have to understand data management, data wrangling, and, in some ways, become a data scientist. That kind of capability requires education and personal investment in skill development. It’s valuable, but it comes at a cost.

Unfortunately, we often ignore those costs when we talk about precision agriculture and ag technology. When we look at adoption rates for sensor-based technology, they tend to be much lower compared to technologies like automated guidance or automated section control.

Take automated guidance, it doesn’t require the same level of human capital investment. Automated section control is similar. In fact, these technologies arguably enhance quality of life.

A good analogy comes from the 1980s, when tractors transitioned from open-air to enclosed cabs. Those new tractors had air conditioning, windows, and radios. Operators no longer ended their day as fatigued, sore, or irritable. The quality of life for the machine operator, and often the rural household, improved dramatically overnight.

Automated guidance works in the same way. With it, an operator can go 20 minutes without steering, look behind them to check the equipment, and even track crop markets on their phone using wireless connectivity. It’s a technology that lowers the cognitive burden and raises the comfort level.

But not all technologies do that. Yield monitors are a perfect example. Yield data is great to have, but it doesn’t automatically improve quality of life, and it absolutely requires a higher skill set to interpret and use effectively.

So, while some innovations reduce the need for human capital and improve day-to-day experience, others increase the demand for technical knowledge without necessarily offering the same lifestyle benefits. That distinction is important when we think about adoption patterns and long-term impacts of ag technology.

Rhishi: There’s a common idea in some VC circles that technology adoption in agriculture does not depend on the farmer’s age or generational cohort. You made the point that if the technology is easy to use and doesn’t require acquiring a whole new set of skills, like with automated guidance, it tends to get adopted. Isn’t it more about how intuitive and accessible the technology is?

Terry Griffin: There’s a lot that breaks down when you look closely at these dynamics. If we focus on the age of farm operators, we see that many are 70 years or older and still serve as the primary decision-makers. Some of them are still out there driving tractors.

Technologies like automated guidance can actually empower older farmers to continue operating machinery longer. These tools reduce physical fatigue and alleviate issues like neck and back strain, challenges that naturally come with aging. In that sense, some technologies may benefit older farmers even more than younger ones.

But age also shapes how people evaluate long-term investments. Take data collection, for instance. The value of data doesn't always show up immediately, it accumulates over time, much like an annuity. If a farmer has 10 or 15 years of consistent data, they can start making meaningful, data-driven decisions.

However, if I’m 70 years old and my planning horizon is less than five years, I probably won’t place as much value on data collection today. On the other hand, if I’m 25 and just getting started, my planning horizon spans decades. So data technologies offer a much higher return over the long run for younger farmers from an optimization standpoint.

That said, I don’t think we can entirely discount generational effects either. Regardless of the century, 18-year-olds tend to act like 18-year-olds. But lived experiences shape each generation differently. For example, many of our grandparents lived through the Great Depression and World War II. Those experiences made them fundamentally different from the generations that came before and after.

Today’s college students, adults, really, were born into a world where the internet already existed. They’ve always had access to the world’s knowledge at their fingertips. That shapes their worldview in ways that are very different from older generations.

And those generational differences affect how people make decisions. If you ask different age groups about loyalty to ag lenders, cooperatives, or service providers, older farmers tend to place a higher value on loyalty. Younger farmers don’t always see it the same way.

But there’s also a financial piece to this. A 25- or 30-year-old farmer might not have the same level of financial independence or access to capital as someone in their 60s or 70s. That limits their freedom to make choices, even if their mindset or risk appetite is different.

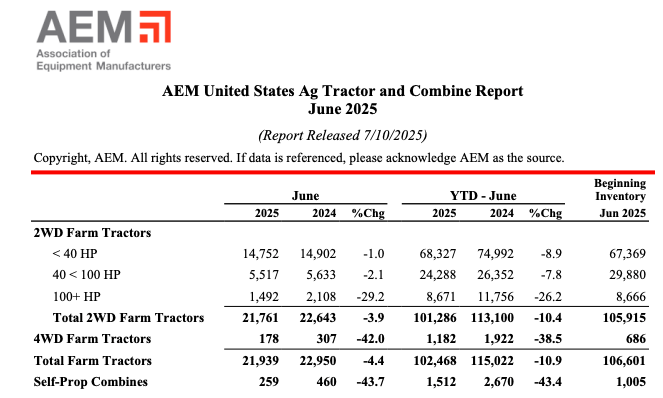

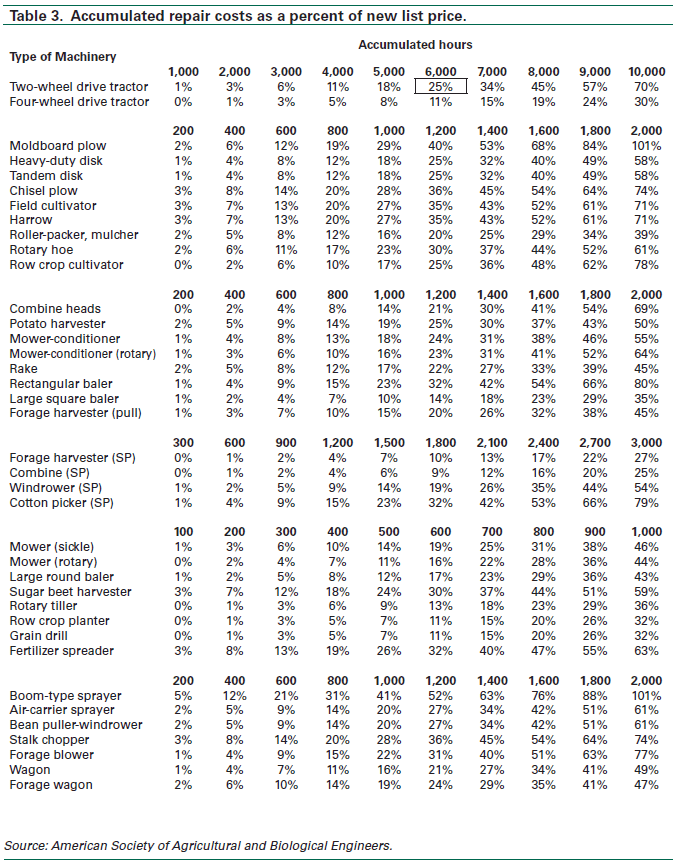

Rhishi: Today’s ag equipment is highly integrated, you have autonomy, telematics, software licenses, all bundled together. But that bundling creates tension. The older generation of farmers expect to use a tractor for 30 years or more. That expectation made sense when the machinery was mostly mechanical.

But now, while the hardware might still last that long, the software requires constant updates, and it can break down much sooner.

Terry Griffin: In terms of subscription fees, the industry has clearly moved toward bundling technology, hardware, software, electronics, hydraulics, into most of the equipment that now rolls off the assembly line. Then manufacturers differentiate pricing by charging subscription fees, betting that farmers will pay to access specific features.

From a manufacturer's perspective, that model makes a lot of sense. We saw something similar 20 years ago in the seed industry. Companies began adding transgenic traits to all varieties, but they only charged farmers in certain geographies, say, those dealing with a specific insect, for the built-in trait. It was easier to embed the technology universally and then price it based on usage.

From the farmer’s perspective, though, it’s a little more complicated. Right now, farmers are navigating subscription fees on tech they feel they’ve already bought. Some are annoyed by the idea of paying an annual fee for capabilities that, in their mind, should be included.

One example is variable rate spraying. With some newer technologies, farmers pay per acre only when they use the feature. And when you run the numbers, it actually works out in their favor, the product savings exceed the subscription cost. But at first glance, it feels counterintuitive, even backward, and that can cause friction.

This isn’t all that different from how social networks or telecommunications evolved. Think back to Friendster, MySpace, Facebook, Twitter, these are networks. And like with the telephone, the value of the system increases with the number of people using it. Economists call that a network externality, where the value of a product or service depends on how many others are using it.

That same concept applies to a lot of AgTech innovations today. Data cooperatives, for instance, only gain value when there’s broad participation. If you're the only farmer contributing data, there’s no real value. But once many farmers join the system, the network becomes exponentially more valuable. The marginal benefit of joining a mature system is high, even if the marginal loss when someone leaves is low.

When I think about automation, I also think about the secondary market, especially for used equipment. Large-acreage farms tend to buy the biggest, newest machines. But in many regions, there’s growing uncertainty around who will buy that expensive equipment once it’s two or three years old. That’s becoming a real friction point.

Now let’s say we move away from a $1 million, cotton harvester, which is a massive, single-use machine, and replace it with $1 million worth of smaller, autonomous machines. If the system is modular, the secondary market becomes more accessible. Smaller farms can buy just a few units from the swarm, instead of the whole fleet. That creates flexibility and opens up options for farms with less acreage.

So I think the secondary market will play a major role in shaping how autonomy is adopted, and in determining who participates in that ecosystem over time.

Rhishi: We need to analyze the full economic cost across the entire lifecycle of the equipment. That means not just the first or second use, but also factoring in salvage value and long-term ownership.

Many farmers, though, still operate with a mental model shaped by past experience, when equipment didn’t have digital sensors, software licenses, or complex electronics. Back then, resale values followed fairly predictable benchmarks. But the newer generation of equipment often doesn’t meet those expectations, which creates a disconnect. Will the secondary market ultimately drive how people value and adopt new equipment?

Terry Griffin: We’re going to see some really interesting developments with autonomy, especially when it comes to subscription models.

I’ve been working with engineers developing automated cotton harvesters, and I built a dashboard for them to explore different pricing structures. One of the ideas we’re testing is based on what economists call a fixed charge. Think of it like a lease, a subscription fee, or even a regulatory compliance fee from a municipality. The concept is simple: you pay a flat fee each week, and as long as you pay it, you can use the equipment as much as you want. Of course, you still have to cover variable costs, but without that lump sum payment, the equipment shuts down, the lease expires, or the system revokes access.

I think we’re going to see more of this model, especially with robots. If a farmer doesn’t pay the subscription or service fee, a signal can be sent to remotely disable the equipment. It’s a new kind of off switch.

Historically, this kind of shift isn’t new. We moved from horse-and-buggies to automobiles, and blacksmiths evolved into auto mechanics. In dairy, we went from hand-milking cows to using robotic milkers. The same people didn’t disappear, they transitioned. They stopped milking cows directly and started maintaining the machines instead. They became technicians.

We’re going to see that in crop production too. We won’t eliminate labor; we’ll shift it. Maybe we’ll need fewer full-time workers, but we’ll need a new kind of worker, robot technicians. For example, with robotic cotton harvesting, someone will still need to set up the “mothership” that delivers modules to the gin. Others will manage the local telemetry systems that could replace traditional GPS.

If we deploy hundreds of small autonomous robots in a field, those units might come in trailers that serve as fixed locations, essentially acting as GPS nodes. Each trailer could emit a localized signal that guides the swarm. This introduces an entirely new infrastructure, and new labor roles to support it.

When I think about labor, I go back to where I grew up in the Arkansas Delta and western Kansas. If you look at a dark sky map, those areas light up, because there just aren’t that many streetlights or homes. There aren’t that many people. And the question becomes: is this a chicken-or-egg problem?

Did the labor force leave because there were fewer farm jobs? Or did farms consolidate and equipment get bigger because there weren’t enough people to work the land?

Either way, we have a labor problem. And autonomy doesn’t solve it by removing people, it reshapes it. We’ll still need people. But we’ll need them with new skills, maintaining machines, managing systems, and working in entirely new ways.

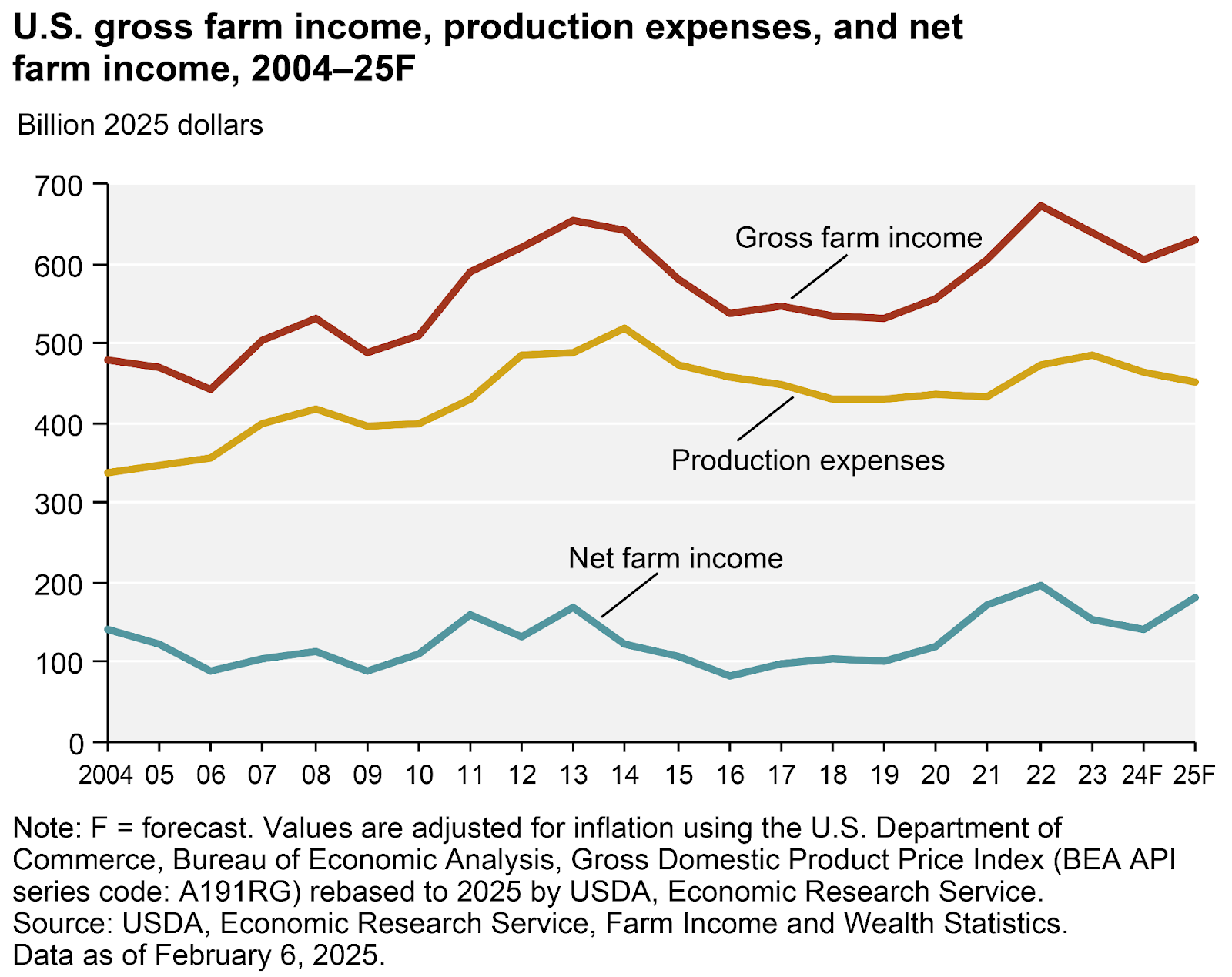

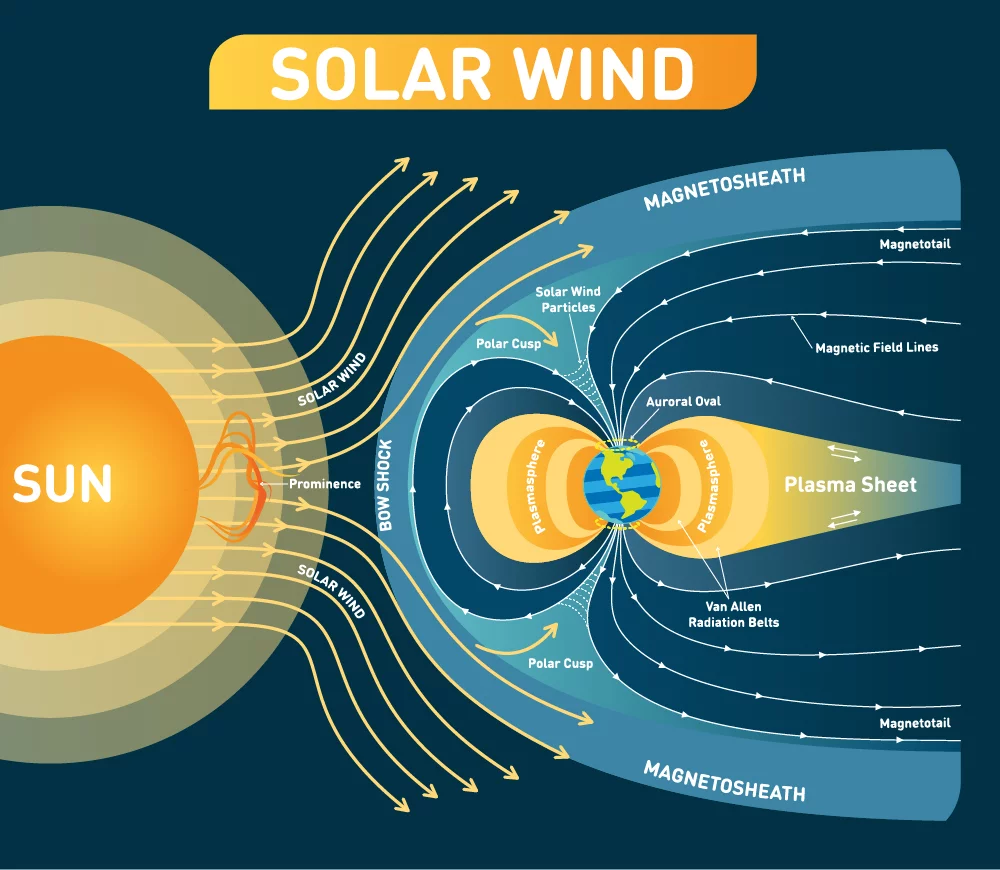

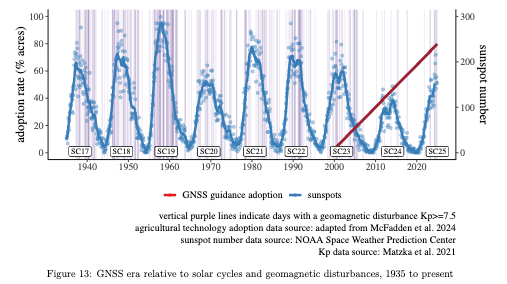

Rhishi: Shifting gears a bit, I’m thinking about all the GNSS outages we saw in 2024 due to solar flares. These are natural phenomena, there’s nothing we can do to stop them, but they have real consequences for farmers who rely on precision guidance.

What did you find in your research on GNSS outages and their impact on agriculture?

Terry Griffin: One of the most interesting things I’ve found in my work is that, even after spending over five years researching and educating the public about GPS outages and space weather, I realized on May 10, 2024, that not everyone had heard the message. People were genuinely surprised when GPS went out, and many questioned whether space weather could really be the cause.

That was a bit humbling for me, honestly. But it also gave me a renewed sense of purpose to keep going.

That evening, we experienced at least four hours of GPS signal degradation. During that time, a lot of planter tractors across the Midwest couldn’t get a GPS lock, which meant they couldn’t plant in straight rows. Some simply had to stop and wait. Automated section control wasn’t functioning either.

Interestingly, smaller farms using older methods, like row markers, just kept going. They didn’t notice anything had happened. So it raises the question: Should we keep those technologies like row markers around just in case? And the answer is, not really.

Despite the reliability they offer during an outage, the economic value of running a 48-row planter on large-acre farms far outweighs the benefit of using smaller, less efficient planters with fallback tools like row markers. On that day alone, the delayed planting likely caused corn yield losses that totaled over a billion dollars. A four- to six-hour delay during such a narrow planting window, especially in states like Illinois, which were already behind due to a wet spring, can push planting from mid-May into early June. And we know that planting in June typically leads to lower yields.

It's important to understand that GPS outages due to space weather are rare, but not zero-probability events. Every 11 years, we reach a solar cycle maximum, and that’s when we see the highest risk of disruption. We just passed one recently, and it should quiet down for the next five to seven years before ramping up again.

The odds of a GPS outage happening during critical ag windows, like May for planting or October for harvest, are fairly low. But it will happen again. What we don’t know yet is how often, or how predictably.

Since GPS became widespread, we’ve only gone through a few solar cycles. The last one was mild, and before that, GPS was still in its infancy. So we don’t have much long-term observational data linking solar activity directly to large-scale agricultural disruption.

But in 2024, we saw it happen, twice. And both times, it happened during planting or harvest.

So yes, space weather can affect agriculture. And it will continue to do so.

Rhishi: Assuming there’s some probability of an outage occurring, like with GNSS, and we can tie that to the economic cost of downtime. How do you model the risks?

When we talk about value at risk, we mentioned that May 10th last year brought an estimated $1 billion loss due to the GPS outage. But the benefits of using large-scale equipment, enough to avoid relying on row markers, easily outweigh that figure over a 10-year horizon. Even if an outage happened every 11 years, which it likely won’t, the overall value at risk is still much lower than the accumulated benefit.

Now, that conversation was really just about corn. If you drive across the U.S., you’ll notice: between New York City and Los Angeles, there are millions of corn acres. Entire states along the interstate can feel like one continuous cornfield.

With corn, space weather functions similarly to terrestrial weather. If it’s about to rain, we don’t change our planting decision. We keep putting seed in the ground until we physically can’t. The same logic applies to space weather, farmers won’t stop unless technology forces them to.

But that’s not true for every crop.

Let’s take peanuts, for example. Peanuts grow underground. You plant them in the spring, then harvest them in two steps: first you dig and invert the plant, then you come back to collect the peanuts.

That process depends heavily on precise location data. You have to know exactly where you planted the peanuts in order to dig them up later. And it’s not just basic GPS, it requires RTK-level precision, down to one-inch accuracy. You need the same AB line for both planting and digging, and that line has to be precise.

If a farmer loses RTK accuracy, during planting or harvest, it creates a measurable yield loss. In parts of the southeastern U.S., Georgia, Florida, Alabama, North Carolina, reports show about an 11% yield penalty just from failing to retrieve all the peanuts because you can’t dig in the exact spot where they were planted.

In that scenario, the farmer faces a real decision.

If we can provide a nowcast, a real-time forecast or alert, about GNSS or RTK signal degradation, that information becomes actionable. The farmer might ask: Do I wait for the signal to return and preserve my RTK accuracy? Or do I keep planting today, knowing I may take a yield hit later?

That choice involves trade-offs. If the farmer waits, they face a biological yield penalty from delayed planting, because everything gets pushed back. If they plant without RTK, they risk 11% loss from leaving nuts in the ground at harvest.

A nowcast could come from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), specifically from their Space Weather Prediction Center, or possibly from the equipment manufacturer. But either way, that forecast gives the farmer power to make a calculated decision.

That’s why I find the peanut example so fascinating. It turns space weather into a management variable. It empowers the farmer. With the right data, they can choose how to mitigate risk and preserve yield.

Rhishi: You also touched on cybersecurity and cyber insurance, especially as it relates to different crops. From an economic standpoint, how do we model the willingness to pay or the willingness to adopt cybersecurity tools or coverage?

Terry Griffin: If I were a nefarious actor, I wouldn’t target an individual farm. Even if I breached a very large operation, the amount of data I could collect from a single farm wouldn’t hold much value for me as a hacker. Instead, I’d go after the places where farm data is aggregated, where I could access information across many farms at once.

When I speak to farmers who are evaluating data service providers, I encourage them to ask those companies what kind of cybersecurity insurance they carry. When we first started having these conversations about ten years ago, cyber insurance existed, but most data companies hadn’t even considered purchasing it. That may have changed now, but it's still one of the first questions I suggest farmers ask.

Farmers value their independence and privacy, and they feel strongly about the data they generate. Their emotional reactions to these conversations are very real, especially when it comes to questions of data ownership and intellectual property.

In countries like the U.S., Canada, and Australia, places with legal systems descended from the British Commonwealth, there are no clear federal or state laws that specifically govern ownership of farm data. In the absence of legislation, data ownership defaults to contracts. And if there’s a contract between the farmer and a data aggregator, chances are the aggregator drafted it, and the terms will favor them. Just like any contract you’d sign when buying a car or a piece of equipment.

So what can a farmer do?

Traditional forms of intellectual property protection, copyrights, patents, trademarks, don’t apply well to farm data. The ag attorneys I’ve worked with agree that trade secret law is the only IP framework that might work here. But trade secrets aren’t automatic. You have to actively protect them.

That means changing passwords regularly. It means restricting access to data. Think of the classic example: Coca-Cola’s formula in Atlanta. Only a few people know it, and they can’t even travel on the same plane together. You don’t need that level of secrecy on the farm, but you do need to put protections in place.

That includes having employees and partners sign NDAs. Rotating passwords for your SaaS logins. Creating a written plan for what happens if a key employee leaves the business. If you don’t take steps to treat something as a trade secret, the law won’t treat it as one either.

For example, putting data on a thumb drive and handing it out to everyone doesn’t count as protecting a trade secret.

If I were a nefarious actor, I wouldn’t waste time on a single farm, unless I wasn’t after data value, but wanted to make a political statement.

Imagine someone who wants to disrupt or discredit modern agriculture, someone who opposes synthetic inputs or modern production practices. If they broke into a dataset and planted false data, for example, suggesting that a farmer over-applied chemicals near an environmentally sensitive area, and that story made it onto the six o’clock news?

That could be devastating. Not just for the individual farmer, but for the whole industry.

Rhishi: When you look at the type of warfare happening between Ukraine and Russia, it’s clear how easily a few drones could take out critical infrastructure. That’s a physical threat, but as you noted, the digital risks are just as serious, if not more subtle.

When you layer AI on top of all this farm-level and operational data, the stakes get even higher. So I’m curious, how are you, as an economist, thinking about data ownership and data value in this context?

Terry Griffin: As an economist, I tend to look at the world through the lens of public and private goods.

A private good is something like a pencil, I can hold it, exclude others from using it, and I can use it up entirely.

A public good, on the other hand, is almost the opposite. You mentioned Ukraine, national defense is a great example. If you’re inside the country and there’s aerial defense, everyone benefits. You can’t exclude someone from that protection, and one person’s use doesn’t reduce its availability to others.

Beyond public and private goods, economists use two other concepts to analyze resources: excludability and rivalry.

Excludability asks, “Can I prevent others from using it?”

Rivalry asks, “Does one person’s use reduce the value for others?”

Let’s say you and I both read the same book. We’re not diminishing the experience for each other. That’s non-rival. Club goods, like Netflix, are a great example, you have to pay for access (excludable), but multiple people can use the service without diminishing it (non-rival).

Common-pool resources, like beaches or bridges, are different. They’re non-excludable but rival, you and I can’t be on the same bridge at the same time if it’s at capacity.

So where does data fall? From an economist’s perspective, data fits more closely with a public good than a private one. It’s generally non-rival and, depending on how it’s handled, often non-excludable.

That’s not a popular view. I’ve been booed during public talks for saying that, it tends to trigger an emotional reaction. But that’s how the definitions line up. It may not be what people want to hear, but it’s how economists understand the framework.

Rhishi: As an educator, how are you thinking about AI on a practical level? What’s the role of higher education now?

Terry Griffin: We haven’t figured this out yet, and that’s exactly the problem I’m seeing.

I’m a father of two college-aged kids. The other day, I mentioned trying to use AI to help with a task, and they immediately stopped me. They said, “Whoa, we’ve already been warned by our university never to use AI for anything.” That’s the message they’re receiving, and it’s made them afraid to use it at all.

But with my grad students, the dynamic is different. I make it clear: don’t bring me something that a computer wrote for you. But I do encourage them to take their own writing or code, submit it to AI, and ask, “How can I improve this?” In that context, I see AI as a tool, a powerful one, but still just a tool.

Using AI to replace yourself?

That’s where the plagiarism concerns come in. But using it to refine your own thinking or troubleshoot code? That’s smart and efficient.

Even before generative AI became a thing, I taught a module on spatial econometrics. One challenge I always gave my students was this: You’re a strong analyst. But how can you automate what you’re doing? How can you replace yourself with an algorithm or a tool? Because if you’re doing high-quality analytics, chances are someone else will eventually build an algorithm to do that same task at a much lower cost. And your best move, as a human, is to figure out how to automate that work before someone else does it for you.

Rhishi: Thank you Dr. Griffin for your time today and your insights on generational attitudes, agriculture economics and how farmers can think about risks, including odd ones like solar flares, and the role of AI.

Go Wildcats!