Agriculture Robotics is difficult AF

Farmwise is winding operations by April 1

This was a tough week for AgTech and FoodTech. Farm robotics company Farmwise has announced its “next chapter” (winding down its operations by April 1st, 2025), seed company Benson Hill has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and plant based food company Havredals also announced a bankruptcy.

We will look at Farmwise a bit more closely in this week’s edition.

When the Alphabet X company Loon shut down, the rationale was that the team had figured out the technology piece, but had not figured out the business and distribution model. Unfortunately, it was a backward way to build a business (highlights by me).

The project was born out of X, Alphabet's self-described moonshot factory for experimental projects, which has also developed the company's driverless car and delivery drone services. Alphabet, however, deemed Loon's business model unsustainable and said it couldn't get costs low enough to continue operation.

"The road to commercial viability has proven much longer and riskier than hoped," Astro Teller, who leads X, said in a blog post. "So we've made the difficult decision to close down Loon."

Application specific robotics is a challenge

Let us talk about Farmwise and agriculture robotics companies for a moment.

Farmwise built a strong team. Their CEO was involved in the original sale of The Climate Corporation to Monsanto for just short of a billion dollars. He later built another food tech startup which was acquired by Kraft Heinz in 2018. Their technology team had some really solid veterans with experience in hardware, and software development for agriculture companies. It shows that an extremely strong team is absolutely necessary for startup success, but is not sufficient.

Unlike Loon, Farmwise tried different business models, including outright sales to large growers, which had the potential to provide an ROI to the grower in a few years, while reducing operational risks.

But Farmwise says the time horizons have been challenging for the company, because while it sees demand for the technology, it needs a longer runway to prove itself and drive adoption.

Farmwise’s Vulcan robotic weeding implement at the back of a regular tractor somewhere in California (Image provided by Farmwise team in July 2024)

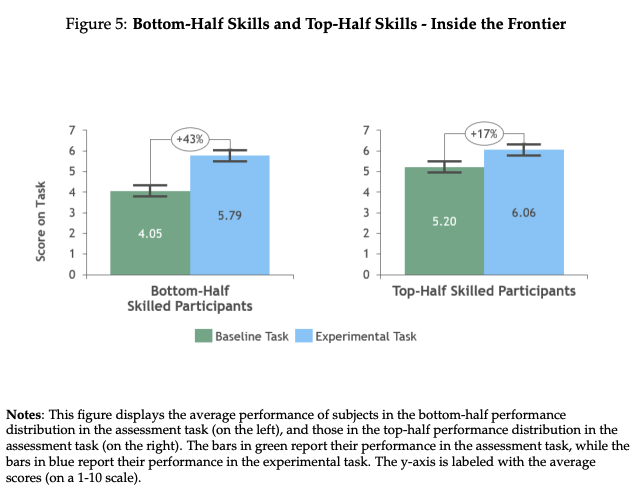

The Expanding 2024 Crop Robotics Landscape report by the Mixing Bowl said the same thing (highlight by me)

Despite significant investment and development effort to date, adoption of crop robotic solutions has been gradual, which is not unusual when introducing new growing practices or technologies in agriculture. When a producer tries something new, they are putting their crop at risk. Some have advocated for a safe-space or neutral production location where startups can test their solutions and not impact commercial production.

Currently, a robotic sale will typically require a pilot program or extended demo of the product on each producer’s acreage, with their specific crop, potentially over multiple seasons. By definition, this will determine the speed of adoption, which will vary by region and type of agriculture.

As far back as 2022, the Agtech So What? Podcast by Sarah Nolet covered the three categories of agriculture robotics autonomy (July 2022), with one of them being application specific agriculture robots built by startups. (The other two were robot platforms and aftermarket solutions)

Startups building application specific agriculture robots have struggled. Farmwise is not as application specific as Abundant Robotics was as Farmwise can do a few different types of operations across a wide range of crops.

Abundant Robotics, a Hayward, California based agriculture robotics company was founded in 2016. It focused on robots picking apples. The company was shut down in 2021, as it was unable to develop the market traction necessary to support its business. The company raised a total of $ 12 million over 5 years.

My fellow AgTech Alchemist and rabble rouser Walt Duflock wrote a refreshing post on why he thinks there are no “hockey sticks” in agriculture robotics. He is very much on point about the challenges. If this is true, it will be difficult to attract capital and it will make it even more difficult to build agriculture robotics startups.

I believe the challenges are even more acute.

To illustrate this point, I will draw on Janette Barnard’s latest newsletter edition about the future of Agtech. (Why all that disappointment could be marvelous for the future of agtech - March 22, 2025) where she questions a bunch of big assumptions inherent within AgTech.

Assumption 7: Total Addressable Market (TAM) in agtech can be huge – prove the value in one segment and hop to the next segment, e.g. specialty crop to row crop, beef to swine, etc.

Reality: Woof. This one has proven incredibly – and surprisingly – difficult. Almost every pitch deck from 2015 to 2022 included expansion into adjacent segments of agriculture, in order to paint a vision of an enormous TAM to justify high valuations, but there’s been a growing realization that this is quite challenging – and there are few examples of it being done effectively.

Building an application specific robot is expensive and hard, but the application of the robot can be limited due to the diversity of applications needed in agriculture. This limits the size of the business of application specific robots.

Picking strawberries using a robot is a very specific application. It requires hardware to “see” strawberries, software logic to decide which strawberry to pick, to move an arm to the right spot in 3D space to cut the stem of the strawberry, to position the basket correctly, and to cut the stem. The robot has to do it fast enough to make economic sense.

It is expensive and difficult to build a hardware and software system which can meet strawberry picking requirements.

Now take the same agriculture robot to pick apples. The strawberry robot has no chance to pick an apple as apples grow on trees.

Mark Brooks, former VC at FMC Ventures made the same point in my SFTW Convo with him last week.

A startup that can “turn the crank” and generate new monetizable assets consistently holds far more value for a venture investor. That’s what makes a company truly scalable and investable. There’s nothing wrong with single-product startups, but from a VC perspective, that broader capability is a key factor that often gets overlooked.

If a company can automate a particular operation for one specialty crop, can they turn the crank and quickly scale the technology to 50 or 100 different crops worldwide and can they expand it to other operations ? If so, it transforms the opportunity into something much bigger.

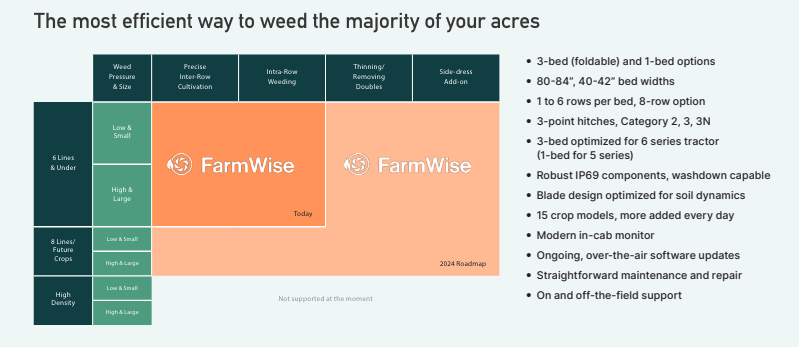

Farmwise has provided some guidance on their roadmap, and the different operations they plan to support in the future.

Image from Farmwise Vulcan 2024 flyer

In the case of Farmwise, they had plans to “turn the crank” but they ran out of time and money to be able to turn the crank.

From my personal experience at Mineral, we were able to support phenotyping for researchers and breeders. We had a hypothesis on how we could “turn the crank” with the machine vision capabilities we had built for other use cases, but we failed to get the proof points in time to prove to our customers and investors that we had a viable long term business.

Mineral is no longer around.

Mark and Janette are saying something similar though they use slightly different terms: “hop to the next segment” or “turn the crank”.

Thin markets is a challenge

Let us say you are able to turn the crank a few times.

How many new incremental customers can you try to service because you were able to turn the crank? This is another challenge within agriculture. Agriculture in North America has the characteristics of a thin market.

Economists refer to markets as thin when they have a small number of buyers and/or sellers, low liquidity, and relatively few observable transactions

Let us take the example of commodity row crops

Even though the commodity row crop market is quite big in production volume, and dollar terms, it is characterized by a few buyers and few sellers. It is basically a thin market, with about 200,000 corn and soybean growers in the US.

We have not seen a strong data flywheel effect in agriculture as it is very difficult to get leverage without distribution. Access to distribution is controlled by incumbents and due to the existing physical infrastructure and relationships.

Even in a technology business in agriculture, the marginal costs don’t go to zero or decline at a fast enough rate. It makes the entry of new players difficult. Given the not-so-large number of commodity row crop farmers (and declining) in North America, there might not be enough business for a new player to reduce the marginal cost of a new customer to a level which makes unit economics sustainable.

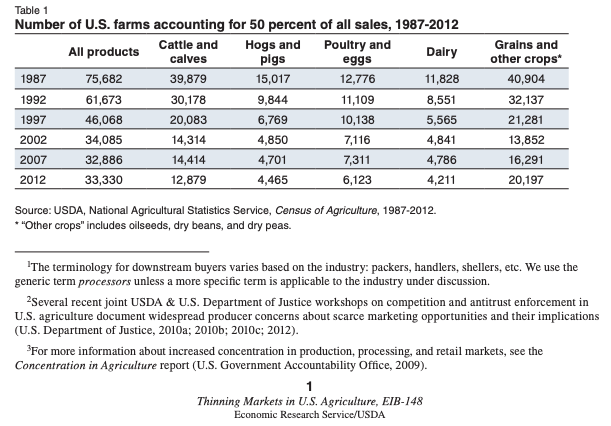

Image source: Thinning Markets in U.S. Agriculture (USDA report from 2016)

Now if you apply the same principles to specialty row crops, the markets are even thinner with a small number of buyers and sellers, when you look at categories of crops. The growing practices and conditions are different, and if you are building application specific robots you don’t have a lot of reps to bring your costs down significantly, before you run out of VC money.

If you take large ticket items like Farmwise or Carbon Robotics, the number of growers who can afford this equipment is very limited. Unless you have a way to dramatically reduce your pricing structure, you might not get enough cycles to drive down the costs to attract more customers.

The large price tag draws out the ROI equation, and extends your timelines to get to profitability. If you combine it with a smaller possibility to “turn the crank”, then your business viability over the long term becomes very challenging.

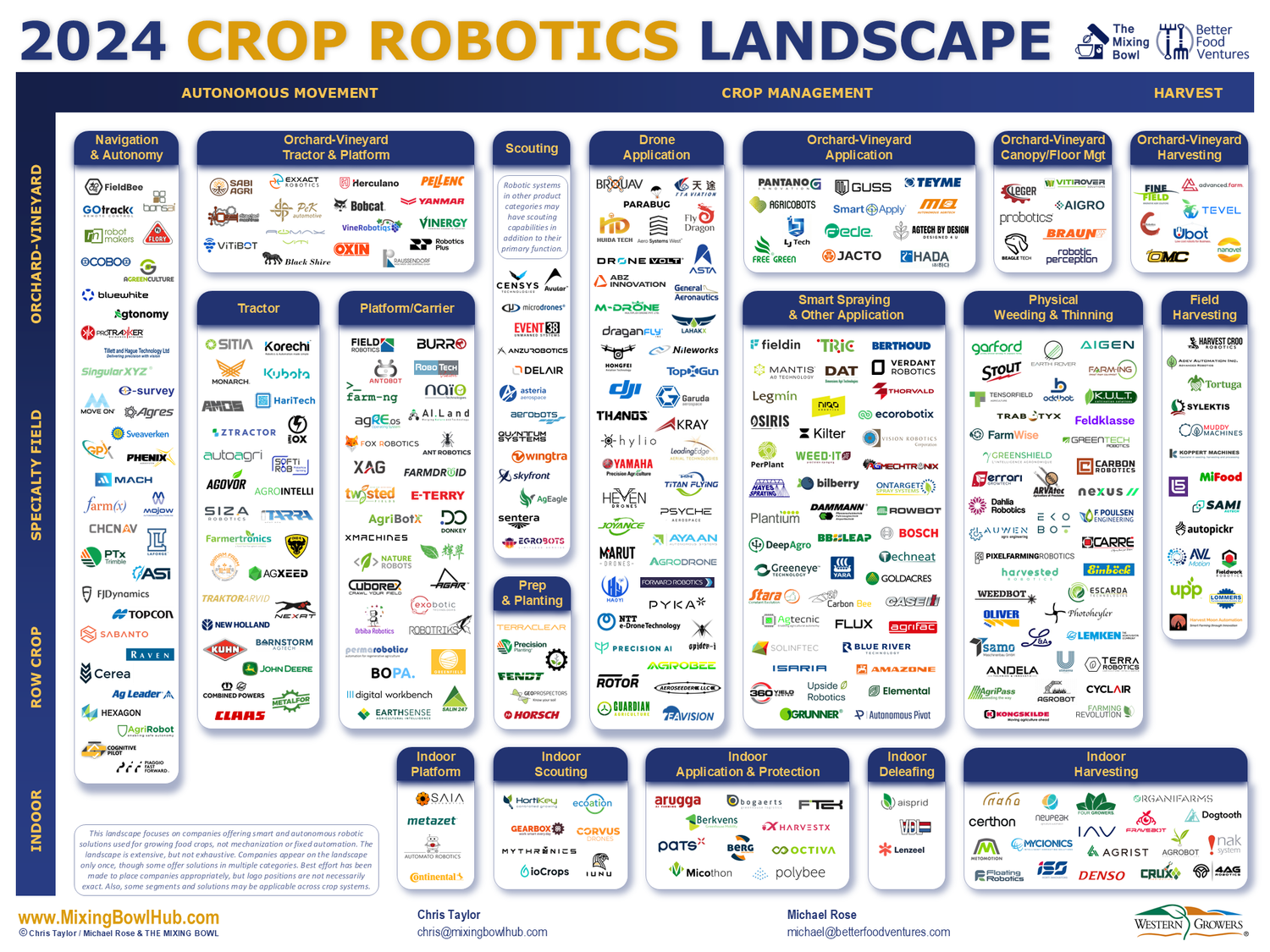

If you look at the Crop Robotics landscape map from the Mixing Bowl, companies which have application specific robots, and cannot turn the crank have a higher risk of failure, unless they completely dominate a category.

Death by Distribution

As Tjarko Leifer, CEO of Farmwise said,

Building a great product is only half the challenge,” he said. “The next chapter is building the distribution and support infrastructure to bring it to scale. That’s where partnerships become critical.

Access to distribution and support infrastructure is a critical issue in agriculture in general and agriculture robotics in particular.

Tim Bucher of Agtonomy had covered this quite well last well in his AgFunder article.

Farmers don’t have the time to waste on agtech startups to manufacture machines that take years to deliver and have yet to earn grower’s trust. A more common-sense approach would be to partner directly with established OEMs and IEMs (integrated equipment manufacturers). These collaborations leverage trusted brands and existing dealer networks, ensuring farmers receive reliable, autonomous solutions that seamlessly integrate into their operations and drive profitability.

The impact of a startup putting 100, maybe 200 units into the field is minimal. — not even a drop in the bucket of what global agriculture needs. But that’s exactly what OEMs and IEMs do. They have the manufacturing capacity plus the dealer network and service center to make sure every machine works in the field, every day.

The challenge we face is existential, but, individually, we can’t deliver at the pace and scale needed. Instead, let’s break the model and collaborate with speed, precision and purpose.

The battle between every startup and incumbent comes down to whether the startup gets distribution before the incumbent gets innovation.

Regulations in California are challenging

Currently, California Section § 3441, Title 8 section (b) states that

All self-propelled equipment shall, when under its own power and in motion, have an operator stationed at the vehicular controls.

This title was written in 1977, when the “Dancing Queen” by ABBA reached number 1 on Billboard 100 and the first Star Wars movie came out!

Due to this regulation, unsupervised autonomous farm vehicles are illegal in the state of California. This is challenging regulation when tractor drivers and labor are scarce and expensive.

With the current immigration policies, the problem will get worse, and this particular regulation will not help. The industry needs to lobby to get some of these regulations off the books.

There is a new paper “Perspective: Closing the Regulatory Gap: Addressing Challenges for Autonomous Agricultural Equipment in California“ which lays out some recommendations to get past some of these regulatory challenges.

Key takeaways

If you are building an agriculture robotics company,

- Try to prove out the basic value proposition of your hardware as soon as possible at the lowest possible cost

- Try to find partners and collaborators through direct relationships with OEMs and IEMs as soon as possible, as laid out by Tim Bucher

- Have a hypothesis on how you can turn the crank and try to get early proof points that you can as alluded to by Janette Barnard and Mark Brooks. This might give you the funds and the time to fight for another day. For example, just like Farmwise, an expensive hardware like Carbon Robotics Laser Weeder might find it challenging to “turn the crank” beyond zapping weeds of a certain size while moving at some slow maximum speed

- If possible, try to build more generic capabilities (a platform play), which can be adapted for multiple use cases. For example, Burro’s harvest assist capabilities can be potentially adapted to other use cases to support autonomy and augment human labor

- Meditate!

Agriculture Robotics is difficult AF!