Amara's Law and Right Benchmarks

Is AI different than previous technology shifts?

Happenings: AgTech Alchemy will be hosting an “AgTech Alchemy: The Whole Hog” event on July 22, 2025 around Tech Hub Live. Do register at the link. Tech Hub Live is offering a $ 100 off on registration if you use the special AgTech Alchemy promo code (Promo Code AATHL25).

I will be moderating a panel titled “AI Tools in Agriculture: What to Know Before You Buy In” at Tech Hub Live in Des Moines on July 23, 2025.

I appeared on Joe Mosher’s “The Pacesetter Pod” with Patrick Honcoop to talk about AI and Digital Strategy in Agriculture. This is a good episode.

Programming Note: I am a big fan of Patrick O’Shaughnessy and what his group has built at “Colossus”. One of the mental models for Metal Dog Labs is to attempt to build a Colossus for Food and Agriculture with a diversity of voices and perspectives.

With this in mind, I am running my first experiment by bringing on Dr. Tuesday Simmons to share her perspective over the next few months about soil microbiome and its importance to agriculture and the development of new technologies.

Starting off with an introduction to the microscopic life inhabiting cropland soils, together we’ll explore the integral role these creatures play in nutrient cycling and soil structure, the relationships they have with plants, how they impact soil health, and what this all means for farming practices and the rapidly growing biological product market.

This will be a once a month series for a few months beginning in July.

Dr. Tuesday Simmons earned a PhD in microbiology from the University of California, Berkeley for research into the effects of drought on cereal crop microbiomes. Post-graduate school, she has worked for start-up companies in R&D, sales, and marketing roles with the goal of effectively communicating the value of cutting-edge biotechnology. As an Application Scientist at Isolation Bio, she worked with leading gut microbiome researchers to improve high-throughput microbial isolation for academic and pharmaceutical purposes. At Root Applied Sciences and Trace Genomics, she has worked to leverage microbiome research for farmers and agronomists. Since 2024, she has worked as a freelance science writer and consultant.

Now onto this week's edition!

Amara’s Law, Roombas and Rough Edges

I. CCAs or LLMS?

With the blistering pace of capability development with AI, questions about technology adoption, and its impact on employment, society and economy are everywhere.

Last week, I gave a talk for the American Society of Agronomy at their Sustainable Agronomy Conference. The topic was “Sensors, Automation, and Digital Agronomy.”

The audience was mostly current agronomists, and students of agronomy and other agriculture sciences. The audience had many questions about what is the evolving role of agronomists, what kind of problems can be solved (or not solved) by AI today etc.

Today, the common trope about AI in agriculture is that at some point in the future the profession of an agronomist will cease to exist and will be overtaken by AI.

I have heard this many times.

In-fact wrote a tongue-in-cheek post about this topic as early as April 2023, with an aptly click-baity title CCAs or LLMS? (CCA = Certified Crop Advisor). It made many people mad at me at the time, especially the ones who didn’t read the whole piece till the end.

I had ended the piece,

How might technologies like robotics, automation, and LLMs augment human intelligence, intuition, and experience and how will it change what it means to be involved with agriculture and farming?

It is CCAs and LLMs not CCAs or LLMs.

The whole discussion brings up an interesting question on how new technology gets adopted, at what pace does it get adopted, and what impact it has on the existing ecosystem.

II. Amara’s Law and the Right Benchmarks

Lately, I begin most of my presentations with a section on historical data about the pace of technology adoption and the empirical underpinnings of it with Amara’s Law.”

We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.

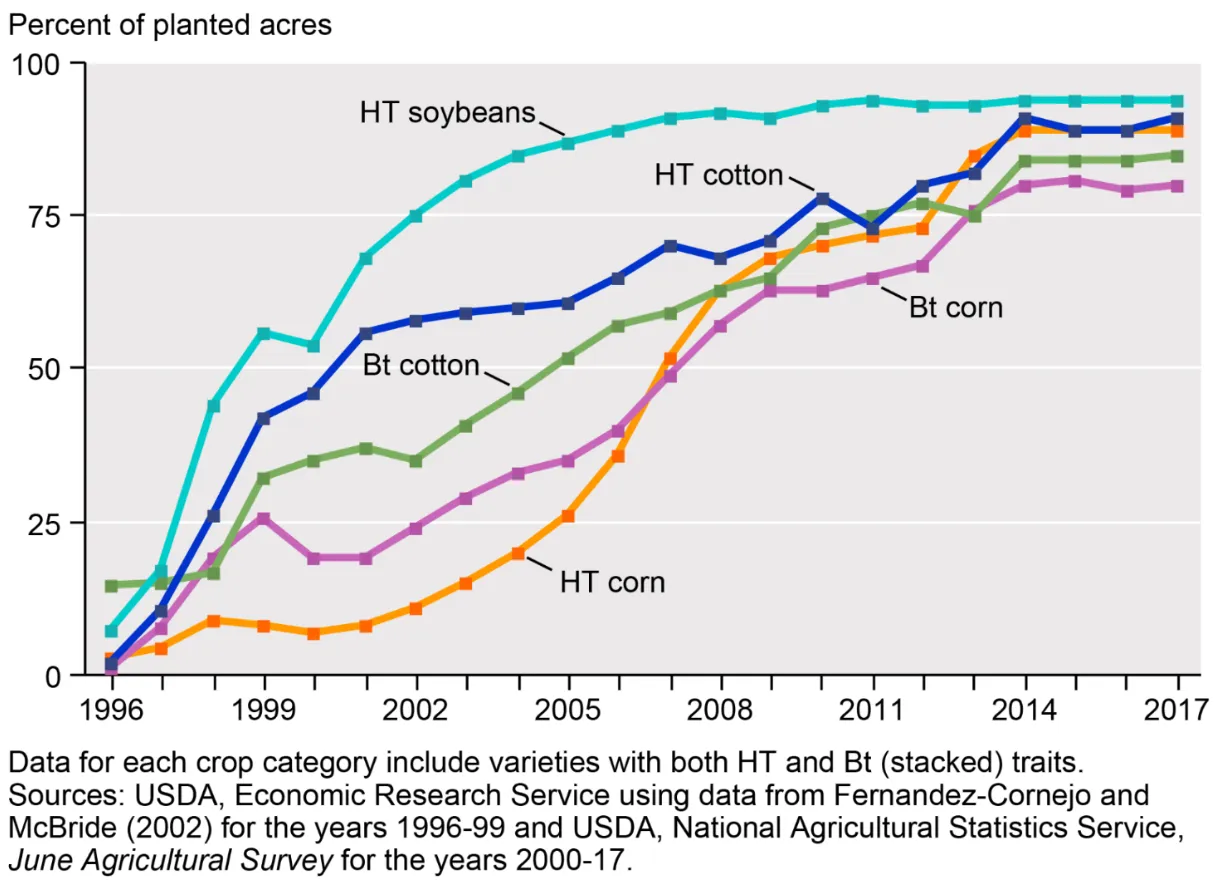

Here is some data on consumer tech, AgTech, and digital tech adoption curves.

The curve for ChatGPT is crazy (though the x-axis unit is different from the previous two charts. For reference, 10 to the power 8 is 100 million)

If we look at the last 25 years, our life today looks very different from how it looked in the year 2000. This is solid proof of Amara’s law, if you think about how much has changed in the last 25 years, but it felt like a lot more was going to change very quickly in the moment.

If we think about Amara’s Law and apply it to the current situation, it is quite possible we are overestimating what a technology like Generative AI can do in the short term.

In the next couple of years, we are all going to be just an energy source for AI and human life will lose all its meaning.

We will be vassals to the AI overlords.

AI will make most of us supremely rich, economies will grow at 25% year-over-year, and we will be sipping pina-coladas, having wild-sex and spending most of our time playing cornhole and pickleball.

It is not clear if any of these futures will come true or not, but it is quite clear none of them are coming true anytime soon.

III. Is this time different?

Some people have laid out scenarios which say AI could lead to 30% explosive growth. Personally, I am extremely skeptical about these wild claims, though I am in the camp that AI could definitely accelerate some growth, and especially help many people in the Global South get access to huge amounts of knowledge and information at a very low cost.

We had similar questions raised about the financial and economic crisis during the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

Economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff laid many of those questions to rest in their 2011 book. "This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly."

The book is a sweeping historical analysis of financial crises across 800 years and 66 countries. The central argument is that financial crises are recurring, predictable, and rooted in the same basic patterns—despite claims that "this time is different."

I believe the adoption patterns for AI and how human beings adjust to it will be very similar to previous waves of technology breakthroughs like the printing press, the personal computer, the internet, and the mobile phone.

IV. What’s the benchmark?

When we think about new technologies, we say “Oh, AI will not replace an agronomist” or “AI will not replace a VC “ (Marc Andressenn).

When we do this comparison we often assume human beings are perfect at the job they do. The question is more about trust and relationship, than being right.

For example, self-driving cars have a much lower accident rate compared to human drivers. We as humans have a tougher time trusting a self-driving car compared to human driving, though it might be much safer for a driverless car to drive you around.

The massive rise of Waymo in San Francisco over the last 2 years is showing that the trust factor is slowly coming in.

It is not too difficult to imagine driving a car by a human might be illegal in the future.

When we talk about agronomists, we have the picture of an expert agronomist who is looking out for you, and someone you can trust to help you with a big decision.

The question is how many agronomists (or take any profession for that matter) fall into this bucket?

Yes, one might argue that with a market driven system, bad agronomists get weeded out and what we are left with are only really good agronomists. Having said that, there is always going to be a distribution curve around skill levels and experience for any profession.

For example, my friend Hollis Robbins talks about AI in the context of higher education.

I’ll just say what my proposal would be: within two years, I think AI will be delivering the general education curriculum for all public universities. And what I mean by general education is writing, critical thinking, some of the baseline classes that most state mandates have decided are a requirement for all college students in public universities around the country. This is delivering information that is already known, and it’s being delivered by a human professor in a classroom, usually an overworked grad student or an underpaid adjunct. I have spent the past seven years as dean at two different places, reading course evaluations, and it is not being done well. So when I say, what is it that AI can bring to higher education, let’s start by asking: Are we doing a good job right now, human-to-human, teaching writing, teaching literature, teaching math, teaching critical thinking, teaching intro to philosophy?

She starts by asking if we are doing a good job teaching. Her benchmark is how we are doing as humans, and can AI do a similar (or better) job at a much lower cost. Her benchmark is not that every teacher at college is the best possible teacher for the subject.

In the context of agronomists, the benchmark question should be

Are we as humans providing the right type of service and expertise, which farmers expect, so that we can make agriculture more sustainable and profitable, and improve our overall food production system?

We should absolutely use technology where we are falling short and the technology can help to improve the quality and cost of service.

VI. Current agronomists in different parts of the world

The United States has had shrinking public budgets and staff, with state and county funding trending down since the 1990s. Commercial advice is concentrated on operations which are greater than 2000 acres. The business model works at large farm sizes as advice is bundled with input purchases and is not feasible for small farms, which are underserved.

The situation is much worse in Canada, which follows a hybrid public-private model, with CCAs filling in a private niche. Canada has a top-down approach. There is patch coverage and inconsistent follow-up. There is a shortage of specialists in emerging areas like soil health, whole-farm carbon planning and integrated livestock-crop advice.

There is high advisor density in NW Europe, but there are capacity gaps in Eastern Europe. There is also a mismatch between policy driven advisory and farm priorities. Many advisors specialize in subsidy paperwork and farmers often less help on profitability and regenerative practices.

Overall small farm and specialty crop farmers do not receive effective services, with affordability and business model constraints being the main barriers. Also, many advisors are trained in conventional pest and nutrient management, with demand for soil-carbon monitoring, biodiversity credits, and regenerative agriculture knowhow outplaces advisor skills.

Farmers increasingly need bundled guidance on markets, finance, and compliance (e.g., EU Green Deal), but advisory silos persist (consultant for agronomy, separate accountant, separate environmental auditor).

Closing those gaps will require new funding models (e.g., vouchers, carbon/eco‑service premiums), adviser upskilling in digital and climate topics, and last‑mile connectivity solutions so knowledge reaches the growers who need it most.

GenAI based advisory services have the potential to reduce the cost to serve a large number of farmers (for example, Digital Green has the goal and can estimate that they can reduce the costs by a factor of 10 compared to their video based advisory services.

A lower cost to serve with a high responsive rate, and high level of accuracy, combined with the experience and knowledge of the farmer’s operation, can allow a single agronomist to serve more farmers at a lower cost.

The declining costs can make the agronomist business model work for small farmers or farmers who are looking for different kinds of advice which a conventional corn-soy agronomist might not be able to provide.

So my silly prediction says that not-only will GenAI not result in fewer agronomists, it might actually increase the number of agronomists as the business model to serve more growers at a lower cost becomes feasible. .

VI. High agency folks drive progress

If the right question is “how can we create better agronomic expertise to make better agronomic decisions?”, then the role of high agency people who want to drive progress becomes very important.

If using GenAI or any other form of AI is one of the right ways to create better agronomic expertise, then we need a large enough group of high agency people to lean into the effort to help create better agronomic advice to drive progress.

For example, Rikin Gandhi and the team at Digital Green is a great example of a high agency founder and team driving the usage of GenAI and AI to bring high-quality agronomic expertise than what is available today to millions of farmers in South Asia and Africa at a fraction of the cost. Most farmers in the Global South do not have access to any or mostly poor quality agronomic advice, as it is very expensive to have people provide 1 x 1 or in a group setting advice.

The low cost of delivering advice through GenAI will require some number of agronomic advisors, and if anything it will create more agronomic advisors, who can service more farmers as it is possible to make a business case out of providing agronomic advice, which can justify the cost of having additional advisors.

Pratik Desai and his team at KissanAI is doing the same (and much more) to help organizations large and small across the globe to bring those services to their staff and to farmers.

Will this cause some agronomists to lose jobs?

Probably.

If you think about the quality and level of agronomic advice available to farmers in different parts of the world (see previous section), you can see that there is significant room for growth and improvement for agronomists both in quality and numbers.

GenAI will play a big role in this transition.

Note: Next week, I will take a look at the rough edges of technology and how human beings adjust their behavior around the rough edges of technology and what are the implications for agriculture.