Andrew Nelson: Balancing the clock speeds of code and crops

SFTW Convo with a farmer who is a software engineer

Andrew Nelson: Balancing the clock speeds of code and crops

Andrew Nelson is a tinkerer. He is always running some or the other experiment on his farm to learn more. He is a fifth-generation wheat farmer in Washington state. He can also write software code. Andrew’s philosophy is to make every plant as productive as possible, reduce the footprint of arable land, and do it with the help of technology. Andrew has worked with hundreds of startups in AgTech and outside. Andrew wants simple to use yet smart technology on the farm, which can be quickly fixed, when something breaks down.

I hope you enjoyed this conversation with a wheat farmer and technologist, as much as I did having it.

Productivity through Technology

Rhishi: In a Nature article you said, “I want to make sure that every acre and every plant is as productive as possible. The fewer acres that are needed to grow food, the more can be saved for conservation. Technology helps me make sure that everything I do on my farm works toward that goal.”

How does this philosophy show up in your daily life?

Andrew Nelson: For me, being able to produce more from our land is incredibly helpful. It allows us to generate more revenue, and hopefully more profit for our farm. But it also lets us steward the land more intentionally. That could mean enrolling in conservation programs or setting aside more areas for things like strips to improve soil and water conservation. That’s something I genuinely want to do.

This approach guides how I manage the farm, and it mirrors the principle of stewardship, both of the land and of our financials. If I don’t care for one or the other the farm won’t survive. I think a lot of farmers, even if they don’t say it out loud, think about that. They want their farm to make it through a tough year, but they also want to leave something behind for future generations, if that’s what the next generation chooses to do.

That’s why I use technology to manage smaller and smaller parts of each field. It’s an ambitious goal to manage down to the level of each plant. When I’m planting 1.2 million wheat plants per acre, going plant by plant sounds kind of crazy. But it’s a bold, exciting challenge. And it gets me thinking: What if I actually could do that?

The better we get at managing on this micro scale, the more we can improve soil health and grow more nutritious food from the same acres. And hopefully, we’ll make our soils more resilient,able to sustain themselves even in harsher climates than they were originally used to.

We’re fortunate in our area. We’ve got deep topsoil, this clay loam that holds onto moisture incredibly well. That’s what allows us to dryland-farm with very little rainfall each year. But I think that’s also made us a little complacent. We’ve relied on that topsoil and haven’t always had to think much about it. But that’s changing. And as conditions shift, we have to think about it more and more.

Ideally, I’d love to see more farmers in our area, because that supports a stronger, more vibrant community.

Ever since I moved back from the Seattle area, that’s what I’ve been trying to move our operation toward.

Rhishi: For most corn and soy farmers the goal is to scale up to reduce per-acre costs and improve profitability. It sounds like that’s not your goal.

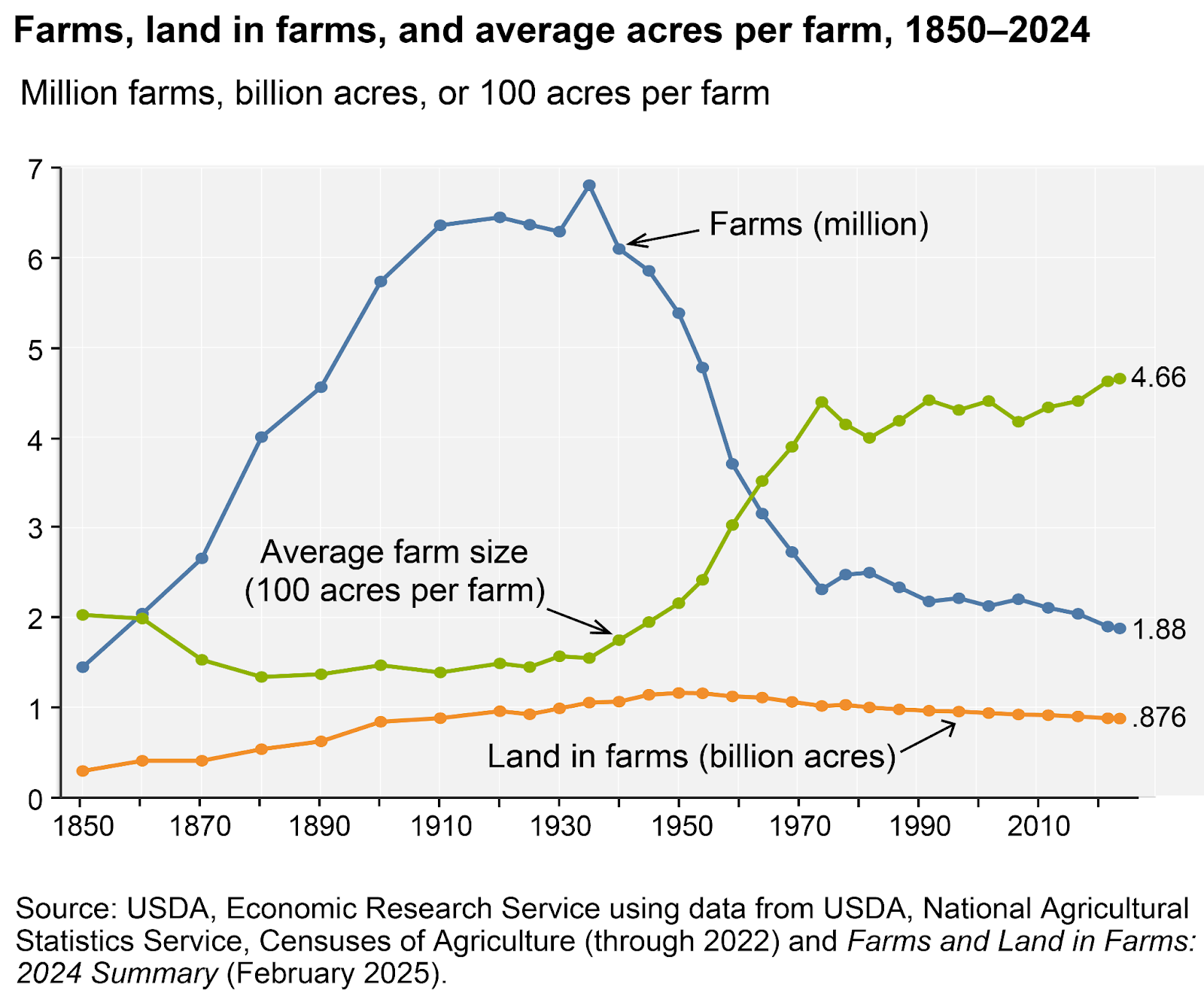

Andrew Nelson: Yeah, that’s true in my area too. We’ve grown quite a bit. When I was growing up, we farmed about half the acres we do now. But I don’t want that pattern to define the future.

When I look at the innovations on the horizon, smaller robots, swarming technologies, I see real potential to avoid the need for massive purchases. For example, instead of buying a sprayer built to cover 8,000 acres, I could deploy a spray robot designed for 1,000 acres or less. That would completely change how we spread costs across acres.

Right now, the reason we buy these big self-propelled sprayers is because of scale. If you’re farming 4,000 acres, you often end up with a sprayer that’s technically oversized, because there’s no practical way to buy “half a sprayer.” Some farmers try to share one, but that’s tricky. You and your neighbor might both need to spray on the same day. Or maybe your neighbor’s an early riser and you’re not, or vice versa. It creates a lot of friction.

That’s why I’m hopeful we’ll move toward a future where smaller, smarter, and more modular implements make more sense. Every time I see a new combine get even bigger, I groan a little. I may eventually have to switch to it, but it frustrates me. Bigger doesn’t always mean better.

And it’s the same story with sprayers. Sometimes I see a new model with 25 or 50 cameras onboard,each one costing thousands of dollars, and I think, “Why not build a simpler sprayer and just feed it smarter information from the outside?”

Future of Agriculture Equipment

Rhishi: Do you think the future of agricultural equipment is heading toward becoming smaller, smarter, and more autonomous?

Andrew Nelson: Maybe we reach a point where we bring all those smaller machines to the same field and just split up the work. That way, not all the operations become harder. Of course, tendering would be a challenge. We'd need auto-tendering systems or something similar to make that workable.

One of the reasons our current equipment gets so expensive is because it has to be so overbuilt. We’re using these insanely hardened steel parts, or massive tires that cost $4,000 or $5,000 each. If we scaled down, and started using smaller machines, the economics could change.

If a tire goes flat, you wouldn’t have to say, “Well, great,that’s another five grand.” Instead, it might just be a few hundred bucks. That kind of scale-down isn’t linear when it comes to cost, it could unlock savings in a lot of ways.

Operationally, I think it still comes back to what kind of intelligence we build into the system. Personally, I want equipment that’s smart enough to operate in the field, navigate, and execute tasks, but I don’t think each piece of equipment needs to make every decision on the fly.

That level of autonomy gets really complex, really fast. With better satellite networks and more reliable connectivity, like we’re starting to see now, we could just have cloud-based decision engines. The sprayer, for instance, could download the map and instructions as soon as it gets to the field.

We keep the hardware lean and focused, and we shift the intelligence to the network or a centralized system. It simplifies things, and it keeps the cost down, without sacrificing capability.

Rhishi: You’re describing equipment that operates in the field, but the actual decisions come from somewhere else, maybe the cloud or a central command system. So it’s not fully autonomous in the way we might think. It’s more like the equipment receives instructions and then executes them.

Andrew Nelson: Part of that comes from the fact that I still work in the field. And what I’ve seen is that the more complex our equipment gets, especially in terms of computers and electronics, the harder it becomes to work on.

Even for me, and I’m a computer engineer.

For my employees, it’s even more difficult. Sometimes, we have no choice but to call someone else in. Even if I own the diagnostic computer and plug it into the combine, that doesn’t always help. It still might not solve the problem.

When I think about labor, I prioritize finding good mechanics and solid field operators. If the equipment isn’t overly complex, that’s what I need. People who know how to run and fix things in the field.

It’s not just about replacing that human skill. It’s about enabling a good operator to watch a robot and say, “Hey, do it this other way.” With tools like large language models, they could just type that feedback in, and the system could interpret it.

If a boom breaks, it should be easier to fix. Compare that to machines filled with wiring harnesses and electronics. Last year, we had a brand new wiring harness on our fertilizer machine,a relatively simple tool with a pump and six fertilizer sections that dribbled product in front of our tillage implement.

Even though it wasn’t a complicated machine, the harness was defective from the manufacturer. But defective harnesses are tough to diagnose because they cause intermittent issues. We tested it, and it didn’t show a fault. But out in the field, you’d turn a corner and suddenly things wouldn’t work.

Eventually, we swapped it out with a different harness,and everything worked fine. So we confirmed it was the harness. That kind of problem wastes time, and it’s hard to troubleshoot.

If we had smaller equipment, we wouldn’t need six sections of control,each machine is its own section. That would simplify things significantly and reduce the number of failure points.

The Dichotomy of Farming and Software

Rhishi Pethe: Farming moves at its own pace. You’ve got natural cycles, growing seasons, and field trials that take time.

In software you write some code, compile it, run it, and get instant feedback. You can learn, adapt, and change things quickly. And you operate in both of those worlds.

To me, those feel like two completely different mental models. How do you hold both of those truths in your head at the same time?

Andrew Nelson: Yeah, part of it comes from my time in software consulting. Back then, I was always thinking from project to project, just a few months out. I realized that my forward-looking horizon was getting way too short. I needed something that pushed me to think longer-term and to work with my hands.

That’s where farming has been so helpful. Now, I think in seasons and years. Sometimes I’m even thinking decades ahead, like whether my kids might want to come back to the farm. My oldest is only nine, but I’m already thinking, What if he wants to be part of this one day? Because that’s the scale you have to plan on. If a piece of land comes up for sale, it’s not just a five-year decision, it’s multi-generational.

Farming has really helped me extend that mindset into the software world. When I write code or consult for an organization, I now think more about how that code will live over time, how it will evolve and function within a larger system. It’s no longer just about solving today’s problem.

And on the flip side, I apply the speed and urgency of tech to how I work with ag startups. I push them hard: You’ve got to get this done by this specific window, or you’ll miss the season and lose an entire year. And for a startup, that’s an eternity. I advise a few startups, and I hope they find my advice useful. But I’m usually the one saying, You need to move now, or this opportunity disappears until next year,and I’m not going to wait a year.

That tension, between long-term vision and short-term urgency, has helped me in both worlds. It’s made me a better software engineer, and it’s helped me become a better farmer.

I run a ton of experiments every year. Some work, some don’t. And if none of them fail, I feel like I’m not testing hard enough. I just want to know what works and what doesn’t, so we can do more of what does.

This year, for example, I ran an experiment with Fox Robotics to keep elk out of our garbanzo bean field. We have a massive herd of elk, hundreds of them, that can wipe out half a field. We set up wildlife deterrents. It was more expensive than I expected, especially in a tough year with a tighter budget. So instead of a full setup, we placed deterrents on the three most well-worn wildlife paths.

To my surprise, it worked really well. That experiment taught me that I might not need to build a full virtual fence. Maybe I just need to run a drone flight, identify the five most-used entry points, and place deterrents there. If the animals change their paths next year, we just move the deterrents.

It’s not about over-engineering, it’s about learning, adapting, and applying just enough intelligence to make things work smarter.

Experiment or Die!

Rhishi: You run hundreds of experiments every year, across all kinds of domains.

What’s your rubric or mental model to decide which experiments to run based on your capacity?

Andrew Nelson: I rely on two main rubrics.

First, I ask whether the task or tool has the potential to save a lot of time or increase revenue significantly. That’s the more standard approach.

Second,and maybe more important for me, I look at whether it’s something that really annoys me, or that I know most farmers hate. Even if I can’t easily quantify the dollars, if everyone universally dislikes it, I tend to prioritize it.

For example, I really dislike busywork and paperwork. So we started using a new accounting service. It turns out even family members want to retire eventually, so we had to figure out how to hand off some responsibilities. I was scanning bills, writing manual emails, splitting things between our two corporations,it was a mess.

So I built a little system using machine learning. It reads the scanned bill, pulls out the dollar amount, splits it automatically between the two corporations, posts it to our tracking page, and sends the email off.

That’s how I think about a lot of improvements.

Rhishi: When you're running experiments, like your field scanning or seed scanning projects, are you thinking purely in terms of solving your own problems? Or are you also thinking about broader applicability?

Andrew Nelson: Usually, I start by building something that solves a problem here, on my farm. And then I think, Okay, this could be valuable elsewhere too. That’s why I’ve been working with so many startups, to take these ideas further and make them more broadly useful.

This year, I’ve been working with one startup that spun out of a Microsoft Research project. We took what we built and made it usable for more farmers, that’s the work we’re doing with AgriPilot. I’m part of that company now, and the goal is to make what we build go further than just my operation.

It’s the same story with UIUC CropWizard. I’ve been working closely with that team too. We started with the idea: Let’s just make something useful for me. And once we did, I could explain, very clearly, why it would be valuable to other farmers as well.

I’d much rather build something that solves a real, high-value problem from day one. And once you’ve nailed that, then you can start layering on additional services to support other use cases.

Flexible design principles

Rhishi: Every farm is different. You mentioned earlier that your land has different slopes, your rainfall patterns have changed over time, and your soil retains moisture really well. But another farmer could have completely different conditions. So if I’m the one building a product for farmers, that presents a real challenge.

If I optimize the product specifically for you, it might not work well for someone else. And if I optimize it for a broader user base, it may fall short for your needs. At some point, I have to draw a line and say, “This version will work for most people, but there will still be some last-mile adaptations required.”

How have you seen companies figure out where to draw that line? How do they know when a product is “good enough” to serve many farmers, without being too narrow or too generic?

Andrew Nelson: Yeah, it’s definitely a tricky problem. My approach is to get something working reliably first, something that performs consistently,and then either work with a farmer to refine it or build it in a way that allows for flexibility. For example, if a farmer needs to swap tracks instead of tires, then make that easy to do. That’s not a big deal for most of us. It’s those kinds of adaptable ideas I hope we move toward.

Honestly, I’m trying to think of a piece of equipment on our farm that hasn’t been modified. The only one that comes close is my sprayer,and even that’s had a few upgrades from the manufacturer. But that’s the only piece I haven’t personally modified in a major way.

That’s why, when I think about robotics, the sprayer seems like the most logical starting point. It’s not that I can’t cover acres efficiently with my current setup, I can,but it’s the piece of equipment I’ve left mostly untouched. That tells me it’s already doing something right, and it might be the easiest function to automate first.

Next year, we’ve got a project lined up with WSU. They’re taking a FarmNG robot and putting a sprayer on it using a standard Raven GPS control system. I really like that idea. Some robots will need to be highly specialized, and that’s fine. But others can function more like tractors, where you can hook up different tools like a sprayer or a seeder and adapt as needed.

That kind of flexibility makes sense.

Rhishi: There are two big questions that come out of that.

First, who should be responsible for those modifications? What does the system need in place to support en users?

And second, should manufacturers bake in that kind of flexibility or modularity right from the start? Should they design their products so they’re 95% complete off the shelf, but explicitly allow for the last 5% to be customized?

Andrew Nelson: In my area, almost every farmer I know tweaks their equipment. They’re not usually adding much in terms of high-tech systems, it’s more hardware-focused modifications. I see that as completely valid, and in many cases necessary.

That’s why I look for manufacturers who overbuild certain components, especially things like the frame. John Deere tends to build bigger, sturdier frames, which is why I often go with their equipment when I know I’ll be modifying it. Not to say I’m exclusively loyal, I’ve got all colors on my farm, but when I’m choosing something like a seeder, I typically go green because the frame can handle more. It gives me a better foundation to build on.

So that’s my general rule: overbuild key components. That gives farmers room to modify, but it also makes the equipment sturdier out in the field. Because things do break out there.

And when something breaks, it’s critical that farmers can fix it themselves. You’re not going to have a nationwide dealership or service network overnight, especially for new or smaller equipment companies. So if a product isn’t farmer-repairable, it’s going to struggle to scale. Companies won’t be able to send out techs for every repair. The only realistic path is to build equipment that farmers can understand and work on.

That’s what I find valuable, not just strong equipment, but repairable equipment.

Rhishi: There might be some robotic applications where you need to build a very specific robot, that’s designed to do just one or two tasks really well.

What are the characteristics or examples of those tasks where it makes more sense to build a dedicated robot?

Andrew Nelson: I tend to default to the mental model of my farm. In general, we can use tractors for planting and cultivation, and they do those jobs well enough. But when it comes to spraying, we’ve noticed it’s much better handled by a dedicated machine. Spraying happens so frequently that it makes more sense operationally to treat it as its own system.

There are other tasks, though, where I think long-term use might justify some form of automation, but the actual window of use is so short that it becomes hard to justify a dedicated tool. Take a weeding robot, for example. If it’s sitting in the field for a couple of months actively working, that’s one thing, it’s busy, like my sprayer is busy. It earns its keep.

But something like smoothing out a field, or even a platform to pick up rocks, that’s only useful for a really narrow window. On our farm, we still pick rocks using hired help and local high schoolers. Depending on the year, we might have to do more or less of it, but the timeframe is always the same: maybe a week or two. That’s it.

So buying a robot or machine that only picks rocks? That doesn’t make sense to me. You’d have a piece of expensive equipment sitting around unused for 51 weeks out of the year.

And honestly, that’s the same reason our combines drive me nuts, they’re insanely expensive, and they sit idle for most of the year, except for maybe five weeks during harvest. It just feels inefficient.

Entrepreneurship in Agriculture

Rhishi: When you work with all these entrepreneurs, have you started to notice certain patterns? Are there specific traits that make you think, “Okay, this founder gets it”?

And on the flip side, what are the most common blind spots? What are the things that founders typically don’t get, that tend to trip them up when they try to build for agriculture?

Andrew Nelson: The main thing people often overlook is just how harsh it really is out on a farm. It’s one thing to say farming conditions are tough, but it’s another thing to actually understand it. I heard this from an engineer who worked on Starlink hardware for John Deere: the vibration levels on farm equipment can be worse than a rocket launch.

The environment is brutal, with dust, vibration, weather, and mechanical stress.

The situation is a double-edged sword. You try to build something rugged enough to survive, and you end up overengineering it. Then it becomes too expensive for anyone to realistically adopt.

The other thing people underestimate is how much grit it takes to work on a farm. Even on my own operation, it’s hard to hire for that. If I bring in a high school or college student to help during harvest, or bring on an intern like I sometimes do ,it’s hit or miss whether they can keep up. I didn’t have anyone this year because I was just too busy, but I’ve seen it before. Some people just can’t handle the long hours. That’s a huge factor.

Because if you’re building something for agriculture, and your mindset is eight to five, that’s not going to work. The equipment, and the people supporting it, need to be available when the farmer is. That means you’re up when your first customer is up, and you don’t shut down until your last customer’s done.

It’s demanding, and I feel for the folks trying to serve this space. If you want to succeed in agriculture, whether you're building tools, supporting equipment, or just trying to be part of the ecosystem,you’ve got to be ready for that kind of commitment. It’s just part of what’s required.

I’ve found that the ones that make the most progress tend to follow that faster iteration cycle.

I also encourage them to run two projects in different areas. Agriculture is so context-specific that spreading things out helps you see how a solution holds up in very different environments. What works in one place may not work in another, so testing across regions or crop types can make a huge difference.

Rhishi: How have the skills you need on your farm evolved over the last 10 years? And looking ahead, how do you think they’ll change over the next 10 years?

Andrew Nelson: I think that as people get more comfortable with AI, farmers won’t need to rely on data analysts or software engineers as much. With software, you can build tools that reach a wide audience using a small team,and I still see that as the direction we’re heading.

But I do see a growing need for people who can diagnose hardware issues in the field, especially with circuit boards and embedded electronics. If someone could quickly figure out why a board isn’t working and even perform in-field repairs, that would be incredibly valuable. Sometimes it’s just a bad capacitor or a component that needs swapping. That kind of skill could save a lot of time and money.

Honestly, I think that’s something I could train my team to do. The people who work for me already know how to weld and handle electrical work. With the right training, they could probably re-solder a capacitor or fix a minor board-level issue.

Last year, an ECU went out at my combine. It was expensive, and I was very grumpy about it. And the thing is, it probably failed because of something really small, a capacitor, a resistor, something simple. Why should we throw away a $3,000 computer when the problem is likely caused by a five-cent part?

That’s the kind of gap I’d love to see addressed, less waste, faster fixes, and more in-field capability.

Rhishi: You work with The Nature Conservancy. You also said that investments in on-farm innovation can’t fall entirely on the backs of startups, that USDA or other institutions may need to step in. What are one or two regulatory changes that you think could really make a difference in enabling more on-farm innovation?

Andrew Nelson: For a long time, it was really hard for us to do anything over the air above our own fields,and that’s been incredibly frustrating for me. The technology has existed for a while, but regulations have made it difficult to implement.

Even now, as we get closer to more general rules for beyond-line-of-sight drone operations, it still bugs me. I keep thinking, Why can’t we just fly beyond line of sight over our own fields? If we could, I’d have access to far better data collection.

That’s a big reason why people are leaning more on satellite data, because the ground-based alternative, which could be much more detailed and provide continuous data collection, is still too hard to use because of regulatory barriers. That’s something that always frustrates me.

Another issue I run into is the constant stop-and-start with projects. That’s been especially true the past couple of months, but even before that, I saw it happen often,where we’d halt something too early, before giving it the time or tweaks it needed to really work.

This is a common challenge with research-type projects. I’ve also seen it in larger companies. A team might say, “This isn’t super profitable, we’re canceling it,” and then six months later say, “Actually, we want to do it again.” But every time that happens, they have to rebuild momentum from scratch.

In agriculture, it’s even worse when that pause hits mid-season. If you stop something in the middle of a growing cycle and try to restart it after harvest, well, now we’re waiting nine months to pick it up again. And that delay resets everything.

Future casting

Rhishi: How do you think farming will look different in 10 years from now?

Andrew Nelson: For me, most of my predictions are short-term, and unfortunately, I don’t think things will change that much in the near future. The way investment flows into agriculture just isn’t the same as in other sectors. Investors tend to treat ag like any other industry, expecting returns on a yearly or bi-yearly cycle, but agriculture doesn’t work that way.

There’s also less capital to go around. Not every segment of ag is wildly profitable, so naturally, innovation tends to focus on the parts of the industry where the margins are higher. That’s understandable, but it limits what gets built.

Now, I do think that if someone can prove out a new technology on something that’s not profitable, that’s a huge win. If your solution works in the tough spots of the industry, where most others wouldn’t even bother, then you’ve got something truly valuable. On the other hand, if your innovation only works in the most profitable areas, you’ve done something, but so could a lot of other people.

I hope we start building implements with less complexity, not more. I hope we realize that loading up every piece of equipment with a million sensors isn’t always the answer. Every sensor is a point of failure. And I’d love to see us move toward simpler, smarter designs that are just as effective, if not more so, because they’re built to last and easier to maintain.

Rhishi: So when you say less, less of what? Less of technology, less of things that can go wrong?

Andrew Nelson: I think in some ways, our equipment is getting a little more advanced, but in other ways, it's still falling behind. There are some huge benefits to certain technologies right now. Take see and spray systems, for example. They don’t really work in my area, but where they do, they allow you to spray significantly less just by detecting weeds in real time as you move through the field.

The problem is, you don’t know how much to fill the tank before you get there. And the technology itself is expensive to add.

What I’d love to see in the future is equipment that doesn’t require a massive upgrade, but still allows for major leaps in functionality. That kind of modular, upgradable design would be incredibly impactful. I’m not saying that’s where the industry is heading, but that’s where I hope it goes.

Because right now, we’re seeing most of the innovation being focused on the biggest players in global ag. And yes, that moves the industry forward, but there are so many more farmers around the world who also need support. They need access to tools that don’t require them to overhaul everything they own, just to benefit from the latest advancement.

If we can figure that out,if we can build more flexible, scalable, and affordable systems, I think that would make the biggest difference.

Rhishi: Thank you Andrew for a fascinating conversation. I was very excited to hear your thoughts on the future of ag equipment and design principles for it, and your ability to work at two different clock speeds between farming and software.