Are we reaching "peak combine-harvester"?

Almost 80% of the productivity improvements in combine-harvesters have come from increase in size and speed. Are we reaching an upper limit?

Are we nearing “peak combine harvester”?

Certain man-made structures and equipment might be reaching their size limits in their current form.

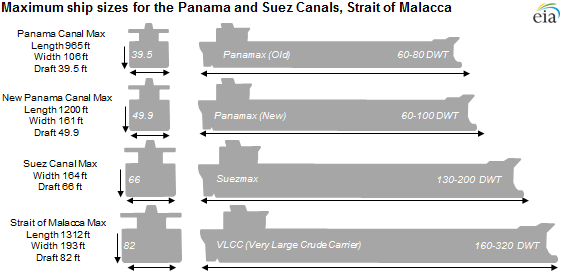

For example, a single ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carrier) oil tanker can hold 2 million barrels of oil, which can fill up 190 Olympic size swimming pools..

Oil tankers today are already at the Panamax and Neo-Panamax standards and tankers larger than what we have today cannot navigate through difference canals like the Panama Canal, Malacca Strait, etc.. (Remember the Ever Green ship stuck in the Suez Canal for almost a week in 2021?) As you can see from the chart below, oil tanker size peaked a few years ago.

Oil tanker design has focused on other improvements like fuel efficiency and emissions reduction through technologies like wind assist, air lubrication systems etc. to optimize the cost of a delivered gallon instead of just going bigger and bigger.

We see a similar phenomenon play out on land, with agriculture equipment like combine harvesters.

Some of the largest and most powerful combine harvesters today have close to 690 hp, weigh up to 50,000 lbs and can harvest 24 acres of wheat in an hour. It seems agriculture has taken a page from the 'bigger is better' playbook, and now our combines are starting to look like they belong in a Transformers movie.

One of the largest combine harvesters today is John Deere’s X9 1100 combine harvester. Its operating width is the same as an NBA basketball court, it is about two SUVs long, and is as tall as a semi-truck.

We have already seen some challenges with extra large combines due soil compaction and logistics issues. Similar to oil tankers, might we be reaching the limits on size for combine harvesters and need to look to other dimensions for continued improvement?

Are we nearing “peak combine harvester”?

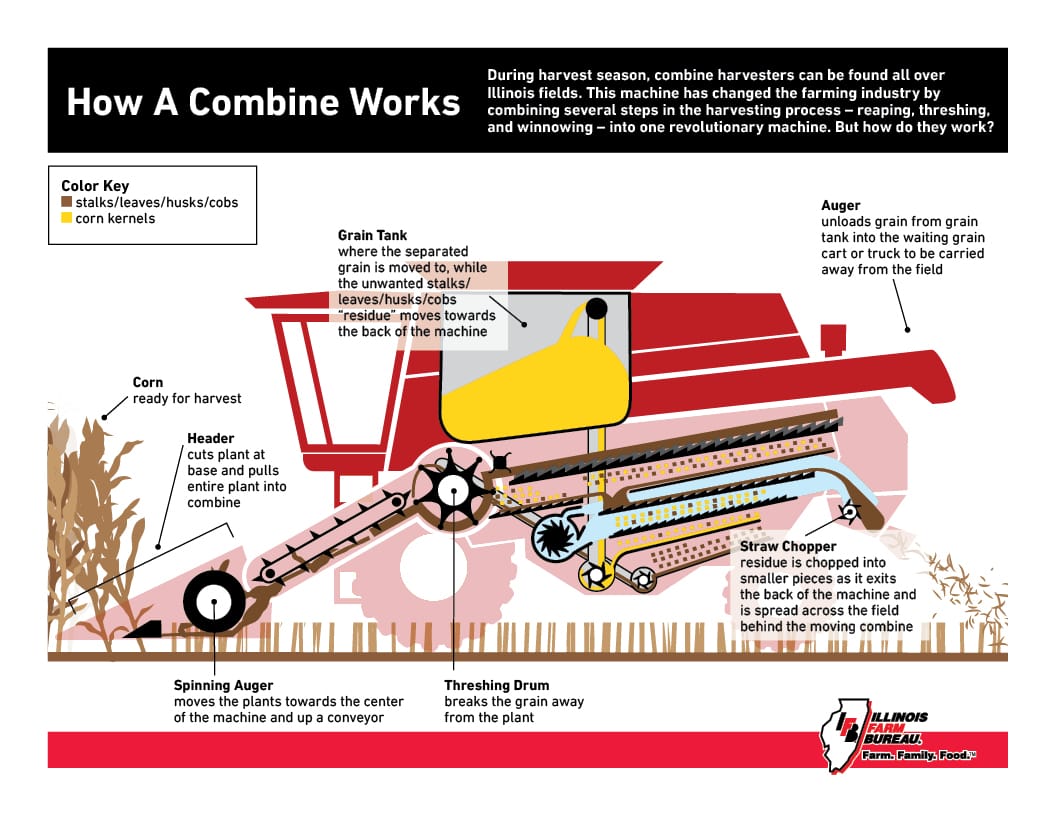

What is a combine harvester?

A combine harvester is a machine which “combines” multiple harvesting operations into one.

“Reaping” involves cutting and gathering the crop in the field.

“Threshing” removes the kernels or seeds of the crop from the rest of the plant, and

“Winnowing” separates the kernel from other plant material like stalks, chaff, or straw.

The first combine harvester was invented in 1835 by Hiram Moore.

It was a large, horse-drawn machine that combined the processes of reaping, threshing, and winnowing grain crops into one operation.

This invention significantly reduced the amount of manual labor required for harvesting, impacting the percentage of Americans working on farms. Combine harvesters are used to harvest crops like corn, soy, wheat, and rice.

Improvements in labor productivity

Combine Harvesters have been improved upon consistently over the last 190 years. Labor productivity improvements for combines in terms of acres harvested per operator hour and bushels harvested per operator hour have happened consistently, with many of the improvements coming through improvements in size, speed, and power.

The productivity of wheat harvesting has gone up 22X in the last 75 years, when measured as bushels harvested per operator hour. Wheat yields have gone up about 3X in the same time period, while labor productivity in terms of acres harvested per operator hour have gone up by 8X.

Of the 8X improvement in acres / operator hour productivity, almost 80% of it comes from improvements in combine harvester width and speed. (If your combining width is larger and you go faster, you can harvest more ground in the same amount of time), as header widths have increased by 3.6X and typical speeds have increased by 1.7X.

One constant through all these labor productivity improvements has been the need of a human operator to operate the combine.

The availability of on-farm human labor in rural areas is becoming more and more difficult day by day, due to out-migration from rural areas.

Drop in farming employment

The increase in size, speed and efficiency of combine harvesters have had a profound impact on US agriculture.

Combine harvesters and tractors led to a productivity boom in agriculture in the United States. The average farm size went from 150 acres in the 1990s to close to 500 acres in the mid 2020s, and the number of farms has gone down dramatically.

The increase in the capacity of combine harvesters have mirrored the dramatic decrease in agriculture employment in agriculture.

Farm consolidation is not slowing down. Farms are getting bigger. And the number of humans available to work on farms is going down or staying constant. The younger generation in rural areas would prefer to work at a Dairy Queen than on a dairy farm.

But we need to continue to improve labor productivity in the future. Where will it come from?

Size as the primary dimension of increased mechanized productivity

The increase in labor productivity in terms of bushels harvested per operator hour has been through a combination of increase in speed, increase in combine-harvester width, higher horsepower, increased yields, and internal improvements around grain handling, with speed and width playing a big role in improvements in productivity (as we saw earlier).

Can you go faster?

The increase in combine harvester typical speed has flattened out. Yes, once in a while you can get a combine harvester to scream down a field at 7-8 miles an hour, but typical speeds have stayed in the 5 to 6 mph range on the higher side.

Higher speeds also pose a set of challenges. Higher speeds result in higher grain loss, poor quality of grain, and safety concerns. In the case of corn, higher speed hits a wall because even though throughput scales with speed, losses and grain breakage scale faster.

The ground speed has to stay matched with the roll speed in a header. If it has to go too fast, the chances of shell loss increases. In the threshing and separation operation, once you go past a critical feed rate, unthreshed kernels and losses rise non-linearly. If you increase the rotor speed, it cracks kernels and chews cobs.

So going much faster might be challenging in the future.

Can you go wider?

Today’s combines can go as high as 50 ft in header width and some latest combines can have up to 60 ft width. (For example, in 2023, Honey Bee unveiled its Airflex NXT flex header at Canada’s Farm Show in Regina. The flex header is available up to 60 feet wide, the largest flex table on the market.)

But there is a limit to how wide can combine harvesters get, without some serious change in the logistics infrastructure of roads, and bridges. Today’s 50 feet combine harvesters with their massive tanks for grain already test escort rules, and field entrances.

Imagine trying to navigate a 60-foot combine down a country road. It is less 'Dukes of Hazzard' and more 'Austin Powers' trying to do a three-point turn in a hallway!

Also large headers can create real world losses due to crop flow, residue management, grain loss, and challenges with following the terrain. The largest headers only work well on uniform flat farm land, uniform crop yields in the field, and ideal growing conditions.

So going much wider might be challenging in the future.

Soil compaction, logistics, and single-point-of-failure

The heavy combine harvesters cause soil compaction, which makes it difficult for plants to grow effectively and creates a drag on future yield drag. (Yields can drag by 10-20% because of soil compaction).

Even with tracks, ground pressure limits what you can carry on the frame like big grain tanks, wider headers, and heavier rotors. The yield drag is one of the biggest challenges when it comes to heavier equipment.

As mentioned earlier, bigger combine harvesters create challenges due to existing road and field logistics.

The economics and the risk profile for one large machine concentrates downtime risk. It is much better to have two mid-size machines, which can often win on uptime and utilization.

Human operator is the biggest constraint

Even though we have made all this progress, a human operator is still needed to operate the combine harvester. This has led to combine harvesters getting bigger, faster and more efficient over the last few decades.

If getting bigger and faster is not a very viable option to increase productivity in the future, what other dimensions are there which can get us the biggest bang for our buck?

In our definition of labor productivity the denominator is always normalized to one operator per combine. What if every combine needed less than one human operator (or no operator at all?)

What if combine harvesters could be autonomous?

Get the operator off the cab!

Many companies are playing and experimenting with autonomy at the farm level. There are already certain operations like tillage, grain-cart management (grain cart is what a combine harvester dumps its grain into) etc. are much further along to autonomously do without a human operator in the loop.

The challenge of reducing the number of humans needed to operate a combine harvester to less than one is still not solved.

But can we decouple the human operator from the combine harvester?

Once we decouple the human operator from the equipment, we can imagine a different type of progress with autonomy.

Next set of bottlenecks post human de-coupling from a combine harvester

So if we might be reaching peak-combine harvester in terms of combine harvester size and speed, and if we are able to de-couple a human operator from the combine harvester, what would be the next set of bottlenecks to think about, in terms of increasing the productivity and efficiency of combine harvesters

It is interesting to observe that many of these bottlenecks and challenges are very similar to the ones encountered by self-driving cars.

Utilization

Today a combine harvester is used only for a few weeks a year, and it is limited to human operator availability. Once the human operator is removed, an autonomous combine can work 24 x 7 in theory and it will be required to solve problems of continuous operation and maintenance, and refueling the combine.

Self driving cars also face the same challenges in terms of continuous operations with high utilization rate.

Swarm approach to increase productivity

In an autonomous system, the productivity could be increased by having a swarm or fleet of smaller or mid sized combines, which could be managed by an in-situ or remote operator or completely autonomously.

The bottlenecks here are the availability of an efficient and reliable system of fleet management and coordination, ability to identify exceptions, and being able to deal with them quickly.

Connectivity

A semi-autonomous or a fully autonomous system cannot work without strong network connectivity, especially in rural areas. Strong connectivity is required for field association, matching with planted areas, and communications with a central control system. Today, rural areas, even in a country like the United States, have a challenge in terms of access to broadband networks.

This is a solvable bottleneck through satellite network connectivity through a provider like Starlink, but it does require investment in rural areas for internet infrastructure. This is less of an issue for self-driving cars, as most self-driving cars are currently in cities, where good connectivity exists for traffic information etc.

Human resources for support and maintenance

When the denominator for calculating combine productivity goes below one, it will require investments in human resources to provide timely support and maintenance when a combine breaks down or runs into problems.

Availability of technical support resources in rural areas is a big challenge today. With a declining rural population, this could be a major bottleneck to improve productivity. Self-driving cars face similar challenges, but to a much lesser extent.

Other non-size related dimensions to continue to work on will include variables which have been continuously addressed over the last few decades.

- Manage downstream costs through better quality of grain output by reducing foreign material and manage residue spread

- Reduce soil impact through optimized routes, fewer passes

- Improve fuel efficiency

Improved operator comfort.This will not be required in the future, as there will not be an operator in the cab).

Conclusion

Given a shrinking labor force, farm consolidation and increasing farm sizes, and the challenges with the ability to find qualified labor, we might be reaching peak-combine (or peak-agriculture-equipment). There is a lot of room to grow productivity with smarter machines through some of the approaches outlined above with the help of automation and autonomy.

We might be just a few years away from peak-combine, but we are nowhere near peak-smart-combine!

I want to provide special thanks to Mike Riggs, Sam Enright, Étienne Fortier-Dubois, Nehal Udyavar, and Andrew Burleson for their feedback for this piece.