Barking up the right tree?

Analysis of AgFunder's call-to-arms for incumbents

Happenings: AgTech Alchemy will be holding its first birthday party in Los Altos on September 24, 2025. Please bring your sun-glasses to the party! You can register here.

Barking up the right tree?

Rob Leclerc of AgFunder wrote a call to arms (How food and agriculture giants are sleepwalking into irrelevance, Sept 11 2025) for agriculture and food industry incumbents to do a set of things based on some observations on investments in R&D, acquisitions, talent, VC investments in agriculture and food etc.

Rob Leclerc is the co-founder of one of the earliest venture funds in agriculture and food, AgFunder. Agfunder has about $ 300 million assets under management, and has invested in 100 companies.

The data show a sector that spends a fraction of its revenue on innovation, files relatively few patents, and captures only a sliver of venture interest. Start‑ups that should help transform the industry are dying from neglect. Meanwhile, tech giants and nimble outsiders are quietly building the intellectual property, data platforms and talent pipelines that will define the next era of technology and outsiders will come for this industry.

And ends with the following warning for the incumbents in the food and agriculture space.

The Great Disruption isn’t a future threat; it’s already underway. Companies can either invest aggressively and shape the future of food, or they can do nothing and become cautionary tales. The clock is ticking.

Even though I agree with many of Rob Leclerc's conclusions (“What should incumbents do?”), there are many challenges on how he builds his case.

Long time incumbents

Before we get into the details, we have to acknowledge that the current incumbents in agriculture (and food) have been around for a long time. In my post “A dominion of incumbents” (March 2023), I had created a table to show how long some of the current incumbents have been around.

Industries which require heavy infrastructure and developing strong physical supply chains are more resilient to anti-incumbency (for example, Tesla is the only new car company which has formed in the last few years, though given the large number of car manufacturers, there is a strong competition among the rest of them).

In my post “Lindy Effect in Agriculture” (May 2025), I had identified four main reasons for these companies to have survived for so long. 1. Distribution 2. Physical infrastructure 3. Fragmented markets 4. Tech innovation and scaling

If you want to disrupt the incumbents, a new player will have to go after one of these four strengths to have a chance to disrupt them, with technology innovation being the most promising.

To go back to Rob Leclerc’s essay, he does make all his points along the technology innovation dimension, and so he assumes (I am not 100% sure about this) that the incumbents will be difficult to disrupt along the first 3 dimensions of distribution, physical infrastructure, and fragmented markets.

Rob Leclerc provides a set of data or makes claims to make his point that incumbents are not doing enough and they carry the risk of becoming obsolete in the future.

Claim 1: R&D Investment is too low

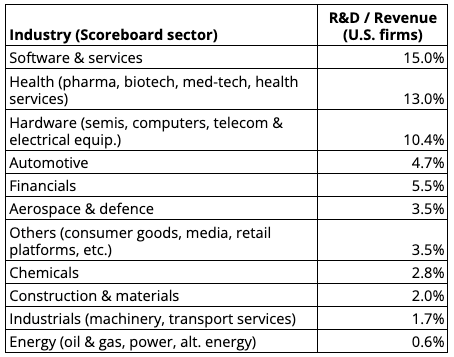

The article makes the claim that the R&D investment by food and agriculture companies by comparing them to tech giants like Alphabet and Amazon by using R&D investment as a percentage of revenue across tech and food, and agriculture.

First off, the food and agriculture industries could not be more different than the tech industry, especially when you use Alphabet as an example. Alphabet and Facebook have the most amazing and one of the most profitable business models the world has ever seen in its history. The margins at internet companies are very different (much higher) and many of them operate in winner-take-all markets.

In a winner-take all market, the risk of lower investment is to lose the entire pie. Food and agriculture incumbents do not operate in winner-take all markets. On top of that, the total addressable market for the tech companies is massive and most importantly it is growing bigger, whereas the food and agriculture total addressable market is not growing at the same rate.

There is only so much food we can eat, and there is only so much land we can farm on. Growth comes from a growing population, though population growth is slowing down, and from people getting richer and eating different types of food. Fiber follows the same logic, and fuel is going to shift to other types of sources in the future.

Also, the current AI era is unlike any other era, when it comes to the size and pace of investments. For example, OpenAI’s recent deal with Oracle is worth $ 300 billion over 5 years, which is almost two and half times the total market cap of John Deere.

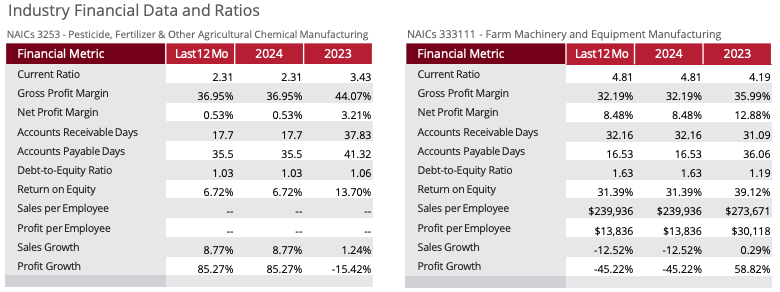

A better analysis would be to look at cross-sector R&D investment rates, and look at industry R&D investment rates over time, and then try to benchmark the R&D investment rates of food and agriculture incumbents.

Based on industry level data, the food and agriculture industry is not far off, but obviously they can do more.

As evidence that tech giants are going after a much bigger prize than is offered by the food and agriculture industry, and the timelines to a smaller prize are longer, we have seen a retreat from food and agriculture by technology giants. I covered this issue in “The Retreat of Tech Giants (from Agtech)” (August 2024)

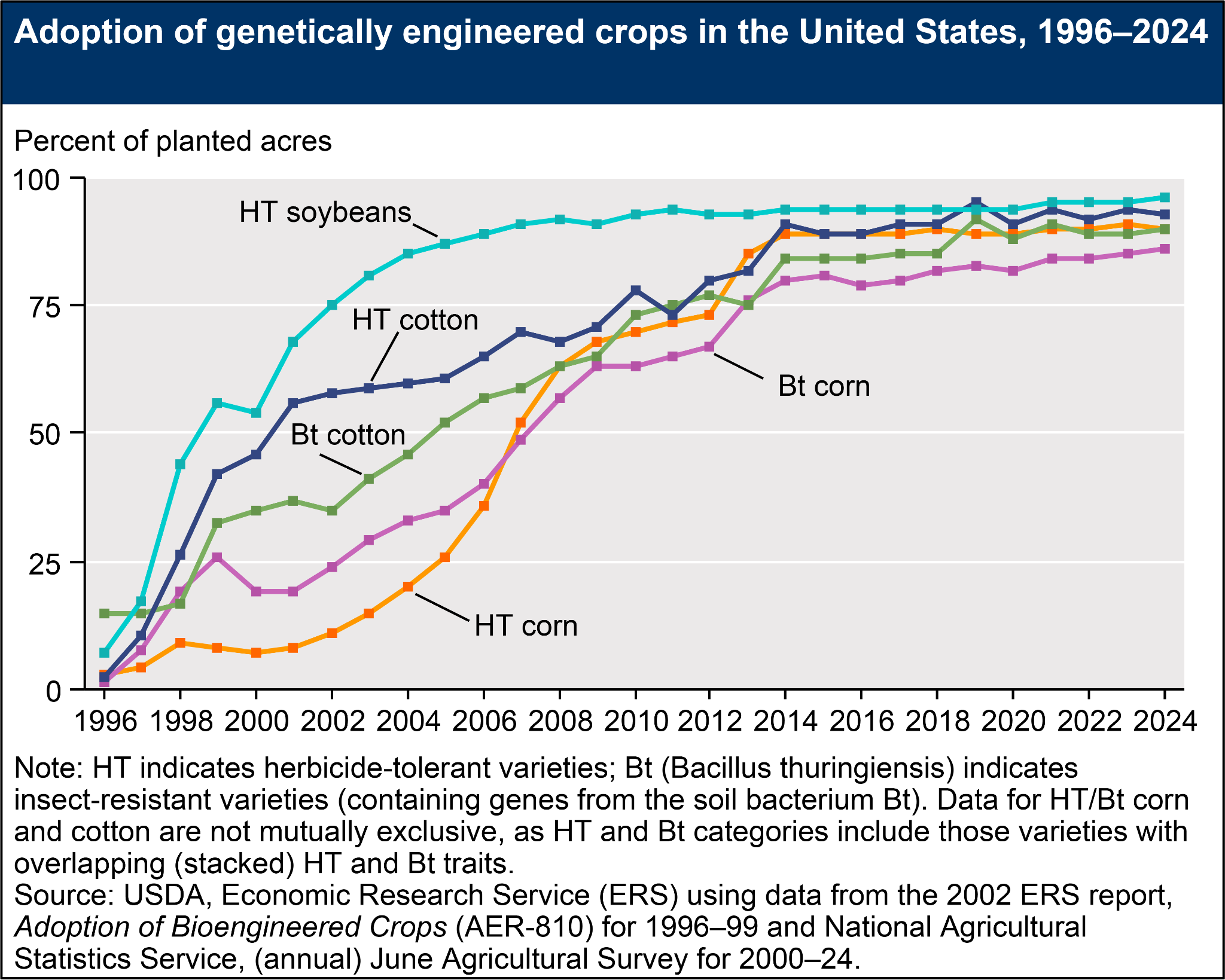

The adoption rates are slow in agriculture. If you are doing a marginally better product, then your revenue potential will not be commensurate with your investment level and your ambition. The opportunity cost for a large tech giant is very high, and so it creates its own investment allocation challenges.

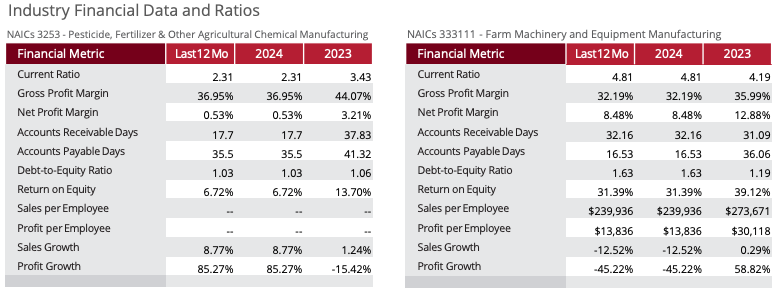

Gross profit margins are very different in tech companies like Alphabet, compared to agrochemical and equipment companies. Alphabet’s gross profit margins are in the 55% to 59% range, whereas they are in the 32% to 37% range for OEMs, and agrochemical companies. With this in mind, it is not a great way to compare R&D investment percentage between agriculture and technology companies.

The article states,

Tyson Foods spends less than one‑third of one percent. PepsiCo and Coca‑Cola report essentially zero R&D expenses.

Coca Cola’s strategy relies on M&A to tap into new markets, new product categories, and new innovations. For example, Coca Cola has acquired companies in alcoholic beverages (Bilssons in Australia in 2024), Body Armor (premium sports drink in 2021), Costa Coffee (Coffee retail and vending technology 2018) and more.

The bottom line is that even though I agree that incumbents could probably spend more on R&D, the comparisons provided in the article are not the best way to build a case, as different companies follow different strategies to get access to new production innovation.

On the incumbent side, the book “Lords of the Harvest” details the story of Monsanto scientists who brought GMO crops to life. Whatever your political stance is on GMOs, you have to admit that GMOs have been one of the most significant innovations of the last 40 years. Given the efficacy of GMO crops, they have been adopted rapidly within the United States.

Claim 2: Food and Ag Companies are not doing acquisitions

Agriculture/food generates a steady but smaller share of global M&A activity (single‑digit % by count) versus the heavyweights in the technology and financial industries. According to Octane advisory’s 2025 agriculture brief, global agribusiness M&A fell by 24% in 2024, with signs of recovery in early 2025.

Given the fragmented nature of the market, M&A activity often skews towards mid-market bolt-ons or roll-ups rather than frequent megadeals. The larger deals (“larger” in the agriculture context) are mostly for technologies which are more applicable across their portfolio. (For example, Climate Corp, Blue River, etc.)

There are other factors which play a big role in the AgTech M&A cycle. Interest rates, farm income and commodity price cycles, and technology adoption curves play a much bigger role compared to technology companies where IP and scale plays a big role. In the case of financial companies, balance sheets and regulatory cycles play a role.

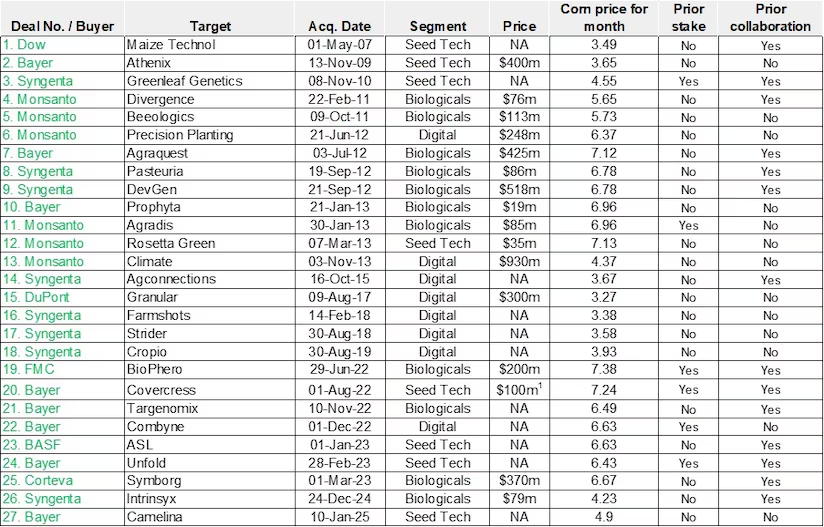

Michael Lee of Syngenta Ventures documented AgTech exits over the last 15 years based on known acquisition prices, and has postulated a hypothesis that higher corn prices create better conditions for acquisitions.

Rob Leclerc’s idea of looking at the stock price and market cap 6 months after an acquisition is strange at best.

The success of an acquisition depends on many factors. Looking at one single data point within 6 months of an acquisition seems like cherry picking. It also looks at the stock prices in isolation, rather than looking at the stock price in the context of what else is happening in the industry and the overall equity markets.

For example, if we look at the example of Bear Flag Robotics provided in the Agfunder article, the stock price of Deere went up by about 1.4% from August 5th, 2021 (day of Bear Flag Robotics acquisition) to February 4, 2025. During the same time, S&P 500 went up by 1.5% (based on the closing stock price for DE and SPY on August 5, 2021 and February 4, 2022). The price increase is the same as the S&P 500.

For Blue River Technologies acquisition, the comparable 6 months numbers are 10.5% for the S&P 500 and 35.5% for Deere. The price increase is much higher than the S&P 500 increase, and could represent a fundamental change in the value of Deere because of the acquisition.

When the data for two acquisitions differ so much even for the 6 month number (which in itself is a flawed measure), and given the small number of acquisitions to go by for publicly available data, it is very difficult to say that all acquisitions are accretive in nature.

It would be much more interesting and informative to see a more comprehensive analysis by taking the data provided by Michael Lee of Syngenta ventures. The analysis should look at factors beyond just a 6 month price bump. If this were true, investors would be putting more pressure on incumbents to make more acquisitions.

Rob Leclerc's example of The Climate Corp’s value to Bayer during the Monsanto acquisition is quite suggestive. I do agree that the presence of digital capabilities was important for Bayer, as it looked to a comprehensive portfolio of seed, chemical and digital capabilities with a global footprint. Bayer might not have acquired Monsanto without Climate, but it would not have just acquired Climate without Monsanto’s seed and chemical portfolio and its strong R&D pipeline.

Monsanto was the seed & traits leader with a strong corn/soy footprint, complementing Bayer’s strength in crop‑protection and selected seeds. The combination aimed to position Bayer ahead of other consolidated ag majors like Corteva, Syngenta, and BASF, and digital was a key piece of the puzzle, but not the only piece.

If the recent discussion about Corteva splitting its seed and crop protection business are true, it signals that agrochemical companies think biotech seeds and biological crop protection each have standalone growth prospects. It also says digital capabilities is a layer and maybe not the core model. It is too early to see how this will play out, but digital continues to be an enabler.

Claim 3: Food and Ag VC has shrunk

This data is widely available.

A smaller amount of VC dollars are not healthy for any sector and food and agriculture is no different. The AgFunder article looks at the 2021 data ($ 51 B in VC investment). My hypothesis is that the spike in 2021 was an anomaly of the ZIRP era. According to the AgFunder article, Agrifood VC is 5.5% of the total VC funding in 2023. That percentage might be lower in 2025 as the Agrifood VC has shrunk a bit more.

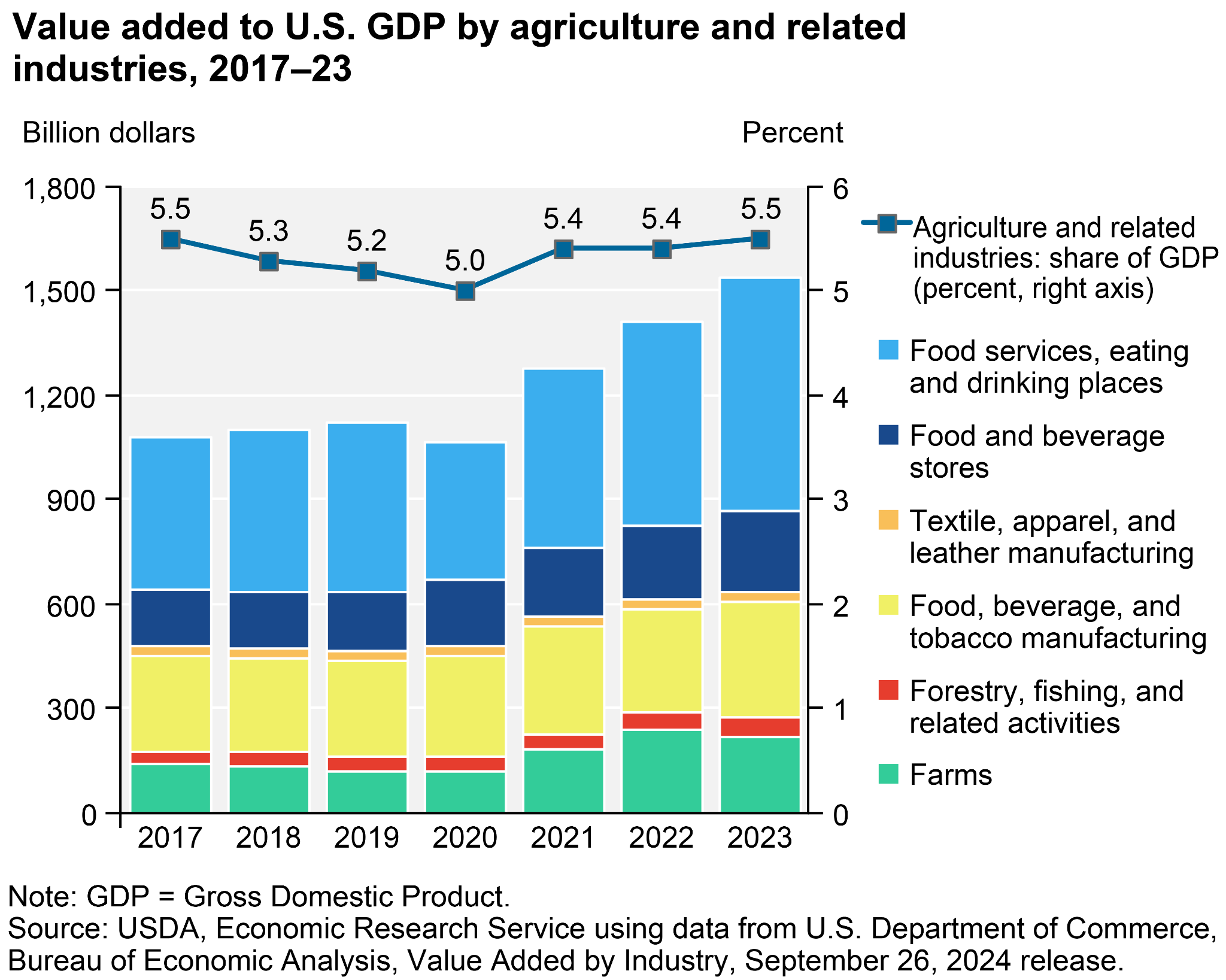

It is important to note that 5.5% VC funding is in line with how much the food and agriculture sector is as a percentage of GDP in the United States. Food and agriculture VC funding might be returning to normal and appropriate levels after the craziness of the CoViD and ZIRP era.

Claim 4: Good ideas suffocated by slow customers

The AgFunder article states,

The issue is that large food and agriculture companies treat innovation like a low-priority side project. The graveyard of failed AgTech startups reveals a deadly pattern: it’s not technical failures killing innovation, but the paralyzingly slow pace of adoption and decision making.

The slow pace of growth in agriculture follows the natural cycles of crops. This makes incumbents naturally risk averse, though some of the examples provided in the article are questionable.

For example, Abundant Robotics had a great product for apples, but it struggled to be adopted to other crops. Terravion’s imagery was too expensive and the insights and outcomes it could drive did not drive enough value to justify the cost. Their unit economics was out of whack.

Please don’t even get me started on vertical farming. You can go and read my article from January 2025. (Vertical farming might have a future, but it might be an idea maybe too ahead of its time)

The AgFunder article continues,

These failures share themes: customers say they want innovation but then balk at paying; partnerships drag on for years and big food and ag aren’t willing to lean in or put real skin in the game; and regulatory or contractual caution smothers momentum.

If a customer balks on paying for something, it is a clear signal that the innovation does not have enough value or the startup does not know how to position it accordingly.

If an incumbent sees value in an innovation, they should be willing to take on the risk of providing the scaffolding to startups to bring them to scale and leverage the incumbent's distribution network to create more value for their customer base.

Claim 5: No tech native executives

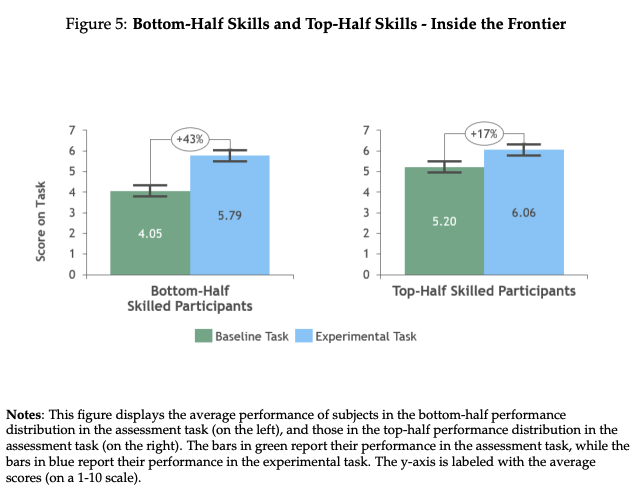

I largely agree with this criticism. As digital becomes more and more prominent, and as AI becomes more and more central to these incumbents operations, they need to lean into those skill sets and capabilities and it has to start from the top. For example, Syngenta has done a really good job with hiring a digitally native CIO and it shows in their progress on digital and AI capabilities.

This is true for AI and tech talent in general. This will be a difficult battle for incumbents to fight, if engineers get paid crazy amounts in other sectors like tech and finance and retail. When it comes to electrical and mechanical engineering talent, food and agriculture is in a much better spot compared to software and AI. Other industries will have to lead with something else. Food and agriculture is uniquely positioned to attract talent based on mission and purpose.

Claim 6: Patent filings: outsiders are racing ahead

The article lists multiple patents from Kubota (which is not an outside agriculture company by the way), AirForestry, and DJI as a signal that incumbents are not filing enough patents. Patents are a good early indicator of R&D activity, but the point made in the article is not very valid.

AirForestry is a drone company which helps with thinning in forests. Airforestry’s drone could potentially be used for some applications in permanent crops, but there are no current applications. DJI and XAG are drone companies from China. China has run away with the drone market, and this issue is not specific to agriculture, but is also an issue for other industries like defense, surveillance, industrials, transportation etc.

The article states,

The first player to aggregate data or secure patents can build insurmountable moats. Tech companies understand this dynamic. Traditional food and agriculture companies have become complacent and still think in terms of physical assets and linear supply chains.

When crops have huge acreage in a given geographical region, (for example corn and soy), thin markets (SFTW - September 2022) play a role and limit the potential upside within that segment.

In large markets with winner-take-all scenarios, it makes a lot of sense. But agriculture markets are highly fragmented along different dimensions of region, crop type, and cropping systems. They do not represent a winner-take-all scenario. The same is the case with the food industry. In this case, it makes sense to play to your strengths, be precise and surgical on where you invest in R&D, and how do you access research effectively.

What should incumbents do?

The article recommends incumbents to double or triple their R&D budgets, create corporate VC arms and acquisition funds, embrace platform economics and invest in the data infrastructure, recruit tech-native leaderships, adopt “fail fast” culture, and have a vision.

These recommendations are fairly plain vanilla and hard to disagree with, as they state the obvious. The scaffolding built in the article to back these obvious recommendations is not solid, as I have pointed out with many examples.

Given the article wants to bolster incumbents, it makes sense to look at some potential areas, which incumbents should pay attention to from a technology standpoint.

“The Dominion of Incumbents” (March 2023)

- CRISPR and Gene Editing using AI

- Fully automatic agriculture equipment operating on the farm, which includes other modalities like drones etc.

- Small size but a large number of smart equipment units operating seamlessly on the farm.

- Use of AI, ML, and large language models across a variety of user experiences, and problem sets.

- Effective alternatives for the current set of inputs, especially chemical inputs.

- MRV tools for tracking sustainability.

- Alternative sources of meat which do not involve animal farming

The confusing part is that as a VC, you are looking to disrupt the incumbents and not bolster them. You want to bring new products to market, which take up a large market share quickly so that you can get a great multiple on your investments.

Is it possible that most VCs realize that the only viable pathway for an exit for the startup is an acquisition by an incumbent? If that is true, it makes sense to have strong incumbents.

Conclusion

The food and agriculture incumbents have survived for a long time. They have leveraged their physical assets, their infrastructure , and their strong technology and commercial teams to maintain their edge and survive for so long. Their physical assets, and their infrastructure will continue to be a strong moat for the incumbents in the future.

As with any industry, incumbents can get disrupted if an upstart comes in with a product which is orthogonal to what the incumbents are.

If people need to give a rallying cry, they need to provide a better scaffolding to make their case, so that more people can heed their rallying cry.