Bridging Science and Policy with Emma Kovak

Senior Food and Agriculture Analyst at The Breakthrough Institute joins SFTW Convo

This post is available for free to all SFTW members.

Welcome to another edition of SFTW Convo. This week’s conversation features Emma Kovak, Senior Food and Agriculture Analyst at The Breakthrough Institute. The Breakthrough Institute is a paradigm-shifting think tank committed to modernizing environmentalism for the 21st century.

Emma works on food and agriculture policy, with a special focus on biotechnology. Emma has researched and written extensively about food and agriculture policy, and the role of innovation and technology.

Emma has a PhD in Plant Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. Emma is a fellow techno-optimist and believes in the power of technology to drive meaningful change in our food and agriculture systems. She takes a very data driven approach in her research and writings, which resonated with me quite a bit.

I have been spending more time understanding the intersection of policy and innovation. Emma is one of the right people to talk with about this topic, especially when it comes to biotech. I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did having it.

Summary of the SFTW Convo

Emma discusses her transition from a PhD in plant biology to working at a policy think tank, highlighting the intersection of environmentalism and biotechnology. She addresses the historical resistance of environmental organizations to biotechnology, the complexities of policy implementation in agriculture, and the role of technology in shaping the future of food systems.

Emma emphasizes the importance of effective policy in supporting agricultural advancements, the disparities in agricultural yields across regions, and the potential of genetically engineered crops in climate policy. Emma and I discuss the impact of insect-resistant crops, the balance between technology and safety in agriculture, and the implications of the EU's anti-GE stance on human health.

She also addresses the MAHA movement's approach to nutrition policy and the role of AI in agriculture. Emma emphasizes the importance of regulatory changes in ag biotech to foster innovation while ensuring safety and environmental sustainability.

Technology and environmentalism

Rhishi: Thanks Emma for joining. How did you go from a plant biology PhD to a policy think tank?

Emma: In grad school, I studied plant biology. I focused on circadian rhythms, which help plants adapt to their environments. That work was firmly on the basic research side, but it ultimately connected to climate change, and that’s what first got me thinking about environmental issues.

During graduate school, I also joined a group that did outreach and education around biotechnology and agriculture, and I found that work exciting, fun, and motivating.

When I started thinking about jobs after grad school, I knew I wanted to move closer to policy and the implementation of technology. I still believe basic research is essential, but I wanted to work in a hybrid space, not surrounded only by researchers in a lab all the time.

That’s what made the Breakthrough Institute such a strong match. I wanted to stay connected to biotechnology, but also work on environmental solutions. And as we know, most environmental organizations haven’t historically embraced biotechnology. That overlap is growing, but it’s still limited.

So joining an environmental NGO that supports technology, not just biotech but innovation more broadly, felt like a great fit. I’m really glad I found that.

Rhishi: You mentioned environmental organizations haven’t really aligned with technology or biotech in particular. What do you think causes that disconnect? And you mentioned that's starting to change, so what's driving that shift?

Emma: I do think that many organizations focused on the environment, biodiversity, or conservation tend to hold a very specific vision of what nature should look like, and that vision often reflects what nature used to look like.

That perspective is intrinsically resistant to change, and it leans away from technology.

I do see more environmental organizations starting to shift. They’re becoming a bit more pro-technology or pro-biotech, mostly because they’re facing the scale of the challenges, climate change, agricultural expansion, biodiversity loss, habitat destruction.

We’re starting to see a broader recognition that we’ll need many different kinds of solutions to address these issues. As these problems persist, grow, and accelerate, I think more people in the environmental space are becoming more open-minded, maybe out of necessity, but also out of possibility.

Rhishi: Earlier you mentioned that you were a researcher during your PhD in plant biology, and now you're working on policy approaches related to technology. What’s surprised you the most in that transition from academia and pure research to what you’re doing now?

Emma: I’ve come to realize that research findings and academic papers play a smaller role in policy decision-making than most idealistic graduate students would hope.

Most staffers are in early-career roles. Some have deep experience, but there’s a lot of turnover, and those jobs require people to cover a huge range of topics, often without being a subject matter expert in any of them. So they frequently rely on external organizations or individuals to bring them the information they need.

And that information has to be concise and highly digestible, not a detailed journal article.

I remember one of the first hearings I attended, it might’ve been about pesticide use, and most of what I heard people say contradicted the research I knew. That moment really struck me.

As an early-career researcher at the time, I was still inside the academic silo, where it feels like what you’re studying is central to the conversation. But outside that world, you quickly realize that research is just one piece of the policy puzzle.

There are many other forces at play, and scientific evidence isn’t always the driving one.

Role and Impact of Policy in Innovation

Rhishi: Based on your experience, what are some of the common misconceptions the public has about the role of policy in agriculture?

Emma: I think people often imagine policy as something neat and linear, which, of course, it isn’t.

Just because Congress passes a policy, funds it, and it sounds good on paper, doesn’t mean it’s going to deliver the impact people hoped for. And that’s frustrating, because even getting to the point of passing and funding a bill is already such a heavy lift.

But beyond that, even when a policy gets through Congress, it might not actually be a good or viable solution, at least not to anyone familiar with the realities on the ground.

The truth is, only a small proportion of these solutions are ultimately effective. The process isn’t clean or fully thought through from the start. It’s messy, and that messiness shows up in the gap between what gets passed and what works.

Rhishi: How much weight should we place on policy when it comes to driving change, versus expecting the industry to lead through technology or new business models? Which areas should a country’s ag policy focus on, and which ones should it leave to the market to figure out?

Emma: Yeah, I think about policy, and especially regulations, a lot.

When they’re well designed, regulations create the structure and foundation for private sector technologies and products to actually have impact. At the same time, policy and public R&D funding can help lay the groundwork for certain types of innovations to emerge.

How regulations are structured also affects which technologies gain traction, and what kinds of problems companies choose to focus on.

So I see policy as playing an important role in both shaping the direction of public sector research, and in influencing private sector priorities through regulatory frameworks.

Public sector R&D funding is also essential because it supports the kind of basic research that companies often can’t, or won’t, invest in, especially when those areas seem less profitable at first.

And as most people in tech know, many of the technologies developed in the private sector are ultimately built on public sector research.

The Future of Food: Technology vs. Climate

Rhishi: Take the ethanol mandate, right? It has had a huge impact, massive, actually. So maybe that’s a counterexample of a regulation that really moved the needle.

I was talking to a friend who works closely with specialty crop growers in Salinas Valley and Watsonville. They were frustrated that California still bans autonomous equipment on farms, even though the state allows autonomous cars on streets, around people! That’s wild.

So clearly, we have examples on both sides. I’ve been following the Breakthrough Institute for quite a while. The article “Technology, Not Climate, Will Determine the Future of Our Food System” really stood out to me. What gives you confidence that it will be technology, and not climate, that determines the future of food?

Emma: Yeah, I really loved writing that piece with my colleagues Alex and Patrick. We pulled together a lot of ideas we’ve shared in different places into one cohesive article. For me, and I think for many of us, the confidence we expressed in that piece comes from looking at both the past and the future of crop improvement.

When we examine the data, the historical trend is striking. From 1961 to 2020, crop yields increased dramatically. I have the number here: even though the world warmed by one degree Celsius during that time (we're nearing 1.5 now), global agricultural output increased nearly fourfold.

And not only did output rise, but we also used fewer inputs like fertilizer and land per unit of output. That’s what we refer to as total factor productivity, a measure of how efficiently we’re producing food. So we’ve already seen a massive boost in agricultural production even as the climate warmed.

Of course, going from one degree of warming to two degrees isn’t the same as going from zero to one, so we shouldn’t downplay the challenge. But this historical momentum gives us some reason for optimism.

One point we made in that article is that coverage of climate impacts on agriculture can be a bit misleading. When people say that climate change is “decreasing crop yields,” many assume that yields are actually falling. But in most cases, yields are still increasing, just not as quickly as they would have in a world without warming.

Take rice, for example. From 1961 to 2020, yields increased by 147%. In a hypothetical world without climate change, they might have increased by 157%. So yes, there’s a 10% difference, but we still achieved a 147% gain, despite a one-degree increase in temperature.

Image source: Note: Originally from Breakthrough Institute analysis.

So far, technology has consistently enabled crop yields to rise, even in a warming world. And we haven’t yet seen a clear break in that trend that would suggest it's coming to a halt.

Rhishi: Did you see any data showing, for example, that yields went up by 200% in one part of the world, and only by 105% somewhere else, but the global average still landed at 147%?

And if that’s the case, what does it mean for those local regions where yields haven’t really increased, they’ve just stayed flat?

Emma: Definitely not. Yeah. The good news is that yields are increasing almost everywhere. They've been growing the fastest in North America. But the bad news is that yields haven’t increased nearly as quickly in other regions.

Sub-Saharan Africa has seen the slowest yield growth.

Increasing crop yields there is incredibly important, not just to reduce local and global environmental impacts while feeding more people, but also to support economic development. Historically, as agricultural productivity increases, incomes tend to rise, and the agriculture sector expands, which then enables industrialization. That pattern has been nearly universal across industrialized countries.

To see yield increases in Sub-Saharan Africa, several things need to happen. Governments need to invest more in agricultural research and development, because current spending levels on ag R&D in many countries are extremely low. Farmers also need better access to inputs like fertilizer and improved seeds, which remain limited in many areas.

Additionally, irrigation adoption is still very low, and improving that could have a big impact.

Of course, this is a complex problem with many contributing factors, and it will take coordinated effort to address. But the need for change in yield growth in Sub-Saharan Africa is urgent.

Rhishi: Based on your data, it feels like climate change has created some drag, even if it’s small, it's still about a 10% drag over 50 years? And as with anything, yield increases don’t show up evenly across the board. So if we look at Sub-Saharan Africa, what kind of policy would you recommend?

First, how do we reduce the drag from climate change? There are probably policy measures that could help there. Second, how do we accelerate the adoption of new technologies, better inputs, improved genetics, more effective fertilizers?

Emma: Yeah, increasing research and development funding for agriculture is really important.

Sub-Saharan African countries can adapt existing technologies and crop genetic improvements, developed elsewhere, to fit local conditions. But doing that effectively requires local or regional research capacity, which makes investing in that capacity essential.

It’s also crucial that governments fund agricultural extension workers. Some of the gaps stem from limited access to technology, but others come from a lack of farmer education and awareness about what’s available to them.

Policy differences in Bio-tech

Rhishi: So basic R&D and adapting better inputs like seeds to the local context, that’s where we’d get the biggest bang for the buck.

When we break down the yield gains we’ve seen over the last 40 to 50 years, about half came from improved genetics and the other half came from other factors. But as a layperson, I feel like we lump all genetics into one big bucket.

Could you break that down a bit? How should we think about the different genetic technologies, how they work and what they’re capable of?

Emma: Like you said, historically, about half of yield increases have come from genetic improvement and the other half from other technological interventions. One major example of genetic improvement is hybrid maize, which played a big role in what people call the Green Revolution. That technology significantly boosted maize yields and saw rapid adoption in the U.S.

Another major example from the Green Revolution is dwarf wheat, which made a massive impact. A single genetic change there led to major yield gains.

Of course, a lot of the genetic improvement that drives yield increases happens incrementally, many small changes over time that collectively have a big effect.

We’ve seen some changes, like hybrid maize and dwarf wheat, that were single, specific breakthroughs with a huge impact. But then there are also progressive, smaller changes, like adjusting the angle of maize leaves, which allows farmers to plant crops more densely or improve how light reaches the plant. It's all about finding the right balance between those factors.

When we talk about genetic modification or gene editing, we’re usually referring to tools that make deliberate, targeted changes.

That’s incredibly valuable, but we also need those ongoing, incremental improvements, like the leaf angle shifts, which have been happening through what's considered conventional or traditional breeding for decades. So even though people often talk about these tools, GMO, gene editing, and traditional breeding, as if they’re completely separate, the reality is they’re all part of the same story. They all contribute to this ongoing trend of yield increases.

Rhishi: Countries that once resisted adopting GMO crops have started to soften their stance. That shift reflects what we talked about earlier, facing all these complex problems without clear solutions, they’re now saying, “We’ve been opposed to this, but maybe it’s time to try it.” And I think that’s starting to happen.

That shift often focuses on yield increases. But you and your colleagues have written a lot about how GE crops actually play a role in climate policy.

Emma: I usually frame this in terms of climate mitigation and climate adaptation, and genetically engineered (GE) crops contribute to both.

For mitigation, one of the most powerful ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture is by increasing yields. When we grow more food on less land, we avoid clearing new land, which is one of the largest drivers of agricultural emissions.

Take insect-resistant crops as an example. They’ve historically faced opposition because they’re genetically modified and produce a toxin that kills insect pests. Understandably, people get nervous when they hear the word “toxin.” But today, between 90% and 100% of crops like maize and cotton are insect-resistant, not just in the U.S., but also in countries like Brazil, Canada, and South Africa. These crops help protect against pests that damage yields and reduce the need for pesticide spraying.

All else being equal, reducing pesticide use should be a win for environmentalists. But of course, all else isn’t equal, there’s a lot of nuance in the debate.

On the adaptation side, we know that climate change is already affecting how farmers grow crops. One major challenge is the growing prevalence and impact of crop pests and diseases. Genetic engineering and gene editing play an increasingly important role here by making it easier to make disease-resistant crops.

Conventional breeding has long targeted disease resistance, but when we understand which genes contribute to vulnerability or resistance, gene editing allows us to target those traits much more precisely. That’s going to be crucial for helping crops adapt to changing climate and growing conditions, and it also enhances what traditional breeding can do.

Rhishi: When you make decisions about which technologies to move forward with, whether to do more testing or apply regulations, you always weigh trade-offs. That’s true across the board.

When you evaluate these technologies, how do you balance the risk of a false positive, approving something that turns out to be risky, against the risk of a false negative, blocking something that could be a real game changer? What kind of mental models or frameworks do you use, or think people should use, when navigating those kinds of trade-offs?

Emma: First, when we look at the history of crop breeding, we see that people have been developing new crop varieties for a very long time, and those crops have consistently been safe to eat. That safety doesn’t come from something inherently safe about conventional breeding as a technology. It comes from the expertise of plant breeders, who know what traits to look for and how to select for the outcomes they want.

Image source: “Here’s what 9,000 years of breeding has done to corn, peaches, and other crops” (2016) Vox.com

That same logic should apply to newer technologies like genetic engineering. People often treat genetic engineering differently because the method for creating new traits is different. But we know that there’s nothing inherently dangerous about the genetic engineering process. Breeders use the same kinds of screening processes on genetically engineered crops as they do on conventionally bred ones. There’s no reason to believe it’s harder to get intended results, or more likely to produce harmful ones, with genetic engineering.

When we think about regulations, it’s important to focus on the product, not just the process. But current regulations for genetic engineering don’t really do that well.

Second, we’re constantly introducing new technologies and altering our environment. Some of those technologies, like fertilizers, have caused clear problems, like nutrient runoff and algal blooms. But fertilizer has also dramatically boosted crop yields, which has helped preserve forests and natural habitats by allowing us to grow more food on less land.

So I don’t think we should fear new technologies, whether that’s a new crop variety or engineered microbes, just because they’re new. We’ve introduced new tools and practices in agriculture for centuries, and we’ve developed good methods to assess and manage their risks. And even when some technologies do create unintended consequences, we keep innovating to solve those problems too.

Agriculture, after all, is one of the most deliberate ways humans change the environment, we alter ecosystems to produce food. So even if we stopped introducing new technologies, things wouldn't revert to a pristine natural state. We’re already shaping the environment, and we’ll keep doing so.

So based on everything I’ve just said, it’s probably clear that I worry more about blocking new technologies than I do about the risks they might pose. And I’m not just concerned about losing one specific breakthrough, I worry about how policy, in general, might discourage innovation across the whole agricultural system.

Opportunity costs of EU’s anti-GE stance

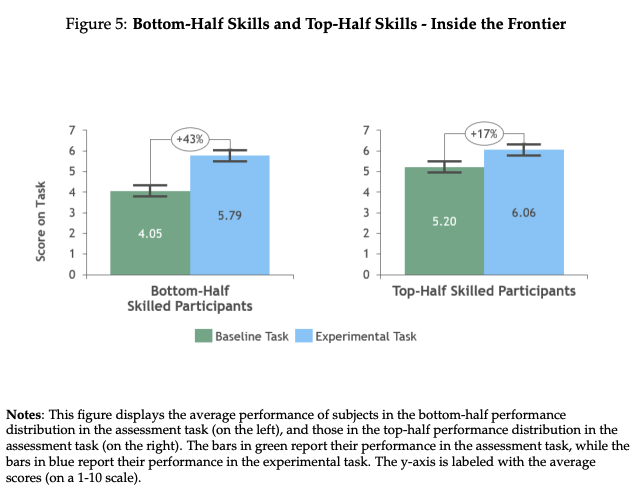

Rhishi: You guys did a really interesting analysis on the EU’s anti-GE stance. You actually quantified the opportunity cost based on some assumptions. The low-end estimate was 171 billion euros per year in lost opportunity. And nearly 40% of that came from human health.

So what’s the link between a pro- or anti-GE stance and human health? Why does that part make up such a big share of the cost? Alternative proteins contribution was marginal, yet we see huge investments flowing into the space.

Image source: “Foregone Benefits of Gene Editing in the European Union”

A new report by the Breakthrough Institute and the Alliance for Science (October 2023)

Emma: I think one of the missing pieces here might be the comparison to the size of the human healthcare industry. It’s not just massive, it’s full of really expensive interventions. So when we looked at the benefits of CRISPR, we broke them into four categories: lower production costs, improved product and service quality, better health outcomes, and reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

One major application of CRISPR is in gene therapies, especially those targeting cancer, either by reducing risk or treating existing cancers. Cancer affects a large number of people, and the cost of treating it is enormous. So the potential for CRISPR to create improvements in both outcomes and cost efficiency in that space is really significant, simply because the problem is so big and so expensive.

Now, alternative proteins also offer a lot of promise. But instead of curing a disease that currently lacks good treatment options, like some cancers, they’re aiming to replace some livestock consumption. That’s a valuable goal, but when you look at the projected growth across these areas, say over the next ten years, alternative proteins still represent a relatively small share of the market.

So when we think about the size of the opportunity and those four types of benefits, a lot of it scales with the current and projected size of the category. And in that sense, healthcare just presents a much larger near-term potential for CRISPR to deliver impact.

Rhishi: What are your thoughts on the whole MAHA movement? They’re focusing on nutrition. But I’m honestly pretty confused about what they’re actually saying, especially when I try to make sense of it alongside the EU discussion we had earlier.

If the goal is to make Americans healthier, where would you focus from a food standpoint?

Emma: Yeah, I find the MAHA movement really fascinating, and honestly, thoroughly vexing.

Of course, I support the goal of making Americans healthier. But I disagree with many of the ways the MAHA movement tries to pursue that goal. Take the recent push to phase out synthetic food dyes and replace them with so-called “natural” ones. I don’t particularly want us to keep using synthetic dyes, they’re probably not good. But natural dyes might not be much better either. Personally, I’d be happy if we just eliminated food dyes altogether.

Still, I think we’re missing some bigger-picture issues. I’m not sure how much the MAHA movement emphasizes this, but to me, access to healthy food seems foundational. We already know that millions of people in the U.S. can't buy fresh fruits or vegetables, either because of affordability or simply because they live in places where those options don't exist. That seems like the basic starting point.

And then there’s this whole debate about ultra-processed food. Honestly, we’re still trying to define what that even means. So I’m not sure where I land on that yet.

Ecomodernist Manifesto

(Note: Alex Trembath and Michael Shellenberger published “An Ecomodernist Manifesto” in 2015.

Rhishi: And shifting a bit more to you personally, and to Breakthrough, you all talk a lot about eco-modernism, and there are different components to that. There's human welfare, biodiversity, and this broader idea of “nature.” How do you personally rank those priorities? What's your own hierarchy, and why?

Emma: For the biodiversity, human welfare, aesthetic notions of nature, I think in terms of biodiversity and human welfare,

I guess I would put those two above the third. And I think that the best solutions that we come up with prioritize both. And they're obviously deeply intertwined.

When you think about land sparing, expanding farmland can benefit humans in the short term, it can increase income, improve access to medical care, and help people afford food. But in the long term, that expansion raises greenhouse gas emissions, and the resulting climate change harms human welfare.

It also threatens biodiversity. So when you weigh short-term versus long-term effects, you're often facing trade-offs that are really tough, because short-term human welfare still matters a lot.

But I really believe that we can often prioritize both, and that’s what we should aim for.

Rhishi: How much time do you spend thinking about AI? What role do you think policy should play in that? I know that’s a bunch of things at once, but we can take it from there.

Emma: I don't currently think as much about AI as I think a lot of people are thinking about it a lot.

Rhishi: Is that just your interest or do you think that it's just a long way to go before AI will have an impact?

Emma: I’m mostly working on federal biotech regulations in the U.S. that affect agriculture. And like I said before, regulations should focus on the final product, not the technology used to create it. So even if someone uses AI to identify beneficial genetic changes in a crop, we should evaluate that crop variety the same way we evaluate one made through conventional breeding. That’s probably the main reason I’m not thinking about AI all that much right now.

Rhishi: In your current work, what excites you the most? What’s the one regulation change you’re really fired up about, where you feel like, if we can make this happen, it’ll be a big win for the whole system?

Emma: It’s partly exciting because a recent lawsuit triggered major changes to USDA regulations for ag biotech, creating a kind of vacuum. That vacuum is actually an opportunity to design better regulations for genetically engineered crops and microbes, which I’m really excited about.

I care about ag biotech regulations because they directly shape the kinds of products developers bring to market. Right now, in the U.S. and in most countries that have agriculture biotech regulations, the rules exempt gene-edited crops, if developers could have made them using conventional breeding or if they don’t contain “foreign DNA”. That obviously incentivizes the use of gene editing in that specific way and discourages the use of transgenics, where you transfer genetic material from one species or organism to another. Gene editing makes small, targeted changes to an organism’s existing DNA, while transgenics allow for entirely different capabilities.

I’m glad to see growing recognition that this regulatory approach seriously influences what technologies developers choose. We shouldn’t disincentivize transgenics, they’re incredibly important. Transgenics allow us to do things that gene editing simply can’t. And while gene editing is exciting and absolutely worth pursuing, we shouldn’t abandon other genetic engineering technologies that still offer unique value.

Rhishi: Is the change you're pushing for going to make it easier to approve transgenic crops too? Or are you hoping both can go faster?

Emma: I want the process to move faster across the board. But for riskier products, I don’t want it to slow down, I just want it to be thorough. I really believe we can prioritize regulatory resources based on the actual risk of the product, not on the technology used to make it.

Right now, regulators often sort products by the type of tech behind them, as if that correlates with risk, but it doesn’t. We need to stop doing that.

Rhishi: The government made that same move with the supersonic flight ban. Fifty years ago, they banned supersonic flights outright as a technology instead of regulating the actual impact, like noise pollution. Now they're trying to change that. They're saying, "We won’t ban supersonic flights, we’ll regulate the impact instead." And that’s kind of the same principle here. We should focus on the risk of the product, not just the technology used to make it.

Thank you Emma for coming onto SFTW Convo. I hope your work will result in innovation friendly policies which enhance human and environmental health.

Additional Reading

- Breakthrough Institute: Clearing a Path To Market for Genetically Engineered Microbe, Gaps in U.S. Regulation of Genetically Engineered Microbes and How the Agencies Can Fill Them (Dec 2024) by Emma Kovak

- Breakthrough Institute: Trump Has an Opportunity to Modernize Agricultural Biotechnology Regulations, The U.S. Needs A Truly Product- and Risk-Based Biotechnology Framework (June 2025) by Emma Kovak

- Breakthrough Institute: SECURE Rule Vacature Creates Opportunity for USDA to Develop Improved Product- and Risk-Based Agricultural Biotechnology Regulations, The Trump Administration Is at a Biotechnology Crossroads (May 2025) by Emma Kovak

- Breakthrough Institute: Can Regulators Keep Up With Biotech Innovation? BRS Must Speed Up Application Review in Order for Gene Editing to Thrive (Feb 2024) by Emma Kovak and Emily Bass