Equipment Lifecycle Economics with Ben Voss

How farm consolidation, resale value expectations, and equipment lifecycles should be considered in equipment design

Welcome to another edition of SFTW Convo. This week’s edition features Ben Voss. Ben was raised on a farm in Saskatchewan. He spent a lot of time developing and modifying farm equipment in his family’s workshop. Right after college, he launched his own company focused on farm equipment design. He spent 10 years in finance and venture capital, ran a PE fund, and then helped a short-line agriculture manufacturer for a few years.

He spent time with Raven and worked through Raven’s acquisition by CNH. He is now a freelancer and is working with a Canadian company called Calian on Agtechnology in a contract role. He wrote two articles on Ag equipment resale values, and what it means for the future of agriculture. The two articles (Part 1 and Part 2) from Ben sparked this SFTW Convo series.

Scaling Regen Ag Starts with Better Data

Farmers Edge is building the digital backbone for regenerative agriculture—designed to simplify Scope 3 reporting and deliver credible results, fast. With Managed Technology Services built for agribusiness, Farmers Edge connects real-time field data to your sustainability goals across every acre and every grower in your network. From in-season tracking to end-of-year proof, Farmers Edge makes regen ag measurable and manageable. If you're serious about scaling impact and reporting, this is the infrastructure that makes it possible.

Summary of the Convo

Ben emphasizes the importance of long-term thinking in equipment design and the need for a deeper understanding of market dynamics in agriculture. He highlights the significance of life cycle economics in the agricultural sector, advocating for a shift in how companies approach equipment design and investment strategies.

Ben highlights the importance of consumer confidence in resale value and the need for a decoupling of technology from machinery design to ensure longevity and adaptability in the agricultural sector. Ben and I explored the evolving landscape of agricultural technology, focusing on the depreciation of farming equipment, the potential of smaller autonomous machines, the need for retrofitters, and the importance of open-source ecosystems.

Rhishi Pethe: You launched your own company, focusing on farm equipment design and manufacturing. How has equipment evolved since the 1990s? How have the ways you design, build, and sell that equipment changed over the last 30 years?

Ben Voss: Since the 1970s, equipment has consistently grown in size, tractors, combine harvesters, planters, tillage equipment, all of it. And that growth has mostly been driven by the increase in farm size. As farms got larger, farmers needed to cover more land in the same amount of time, so they turned to bigger equipment to stay efficient.

But that shift also meant fewer and fewer people stayed in farming. As farms scaled up, the number of farmers kept shrinking, even though the overall land base stayed fairly constant. Globally, we’ve seen some land reduction, though places like Brazil are still expanding.

In North America, though, the pattern is clear: bigger farms led to bigger equipment. For example, in 1990, a typical planter or air seeder might’ve been 35 feet wide, maybe 49 feet if you were a large operator. Today, machines commonly span 80, 90, even 110 feet. And modern combines? They’re now 10 to 15 times more productive in terms of bushels or acres per hour compared to what farmers used back then.

It didn’t all happen because of the equipment. Farm sizes and equipment size grew together. If you’re a farmer and you say, “I want to scale up,” and then ask, “Can you build me bigger equipment?”, sure, those conversations happen. But the equipment companies mostly respond to what the market asks for. They’re reactive.

They rarely think beyond that. Most R&D cycles for equipment run about five to seven years. So if you start developing something today, you’re expecting to sell it in five years. That makes it easy to get fixated on solving the immediate problem. Engineers design to the specs they’re handed. They usually don’t factor in the commercial or financial implications, they leave that to the CEO, CFO, and other execs to sort out later.

And when leadership finally steps in, they mostly look at trends and historical context. Most companies just want to say, “We grew 5% or 20% year over year,” and hit that number. But if you ask, “Okay, what if you could grow 20% for the next five years, but then collapse after that, would you stop what you’re doing?” Almost no one says yes. No one stops to think, “Wait, maybe I’m creating a long-term risk for short-term gain.”

I’ve seen that story play out hundreds of times. A classic example, not from agriculture, but still relevant, is the story of the ice industry. Before refrigerators, we had a massive industry that harvested and sold ice. That’s why we called them “ice boxes.” When refrigerators came along, those companies were the first to be offered the chance to sell them. They already had the distribution network. But they refused. They said, “Why would we sell something that cannibalizes our own product?” And they stuck with ice, until the industry disappeared.

And in agriculture, we’re kind of famous for that, for being our own worst enemy sometimes. We focus too much on individual competitive strategy and not enough on the bigger picture. That’s part of why I felt the need to do some deeper analysis, to help the industry step back and really think things through.

Power law for VC investment

Rhishi Pethe: VCs usually take a long-term view, right? A fund typically runs for 10 years or so, depending on when you join. So as a VC, do you think about problems differently than, say, an Ag equipment company would? What kinds of decisions do you make as a VC that are fundamentally different from the ones you'd make in an operating company?

Ben Voss: There are really two kinds of VCs. First, you’ve got purpose-driven VCs, they manage money with a mandate. Someone gives them capital and says, “Invest in startups or companies because I want to achieve a specific outcome.” Then there are VCs focused purely on wealth creation. They invest in high-risk ventures with the hope of generating big returns. Their goal is simple: make a lot of money from a few breakout successes.

You can think of purpose-driven VCs as somewhat similar to corporate VCs. A corporate VC might invest in startups not just for financial return but for strategic benefits, like gaining insight into innovation, shifting company culture, or tracking emerging trends. Financial leadership still tells them not to lose money, but those non-financial outcomes carry real weight.

When I worked in VC, I managed purpose-driven money. My goal was to find startups that supported local economies and economic development. Later, in private equity, the capital still came with a strategy, every investment aligned with a larger purpose.

I’ve played a role in the Ag economy and continue working with startups. What I’ve noticed is that money flowing into AgTech has often been driven by the dream of finding the next big exit. Investors hoped to back a game-changing company that would get acquired by a major corporate player, delivering a huge return.

And yes, a few companies did pull that off. But 98% didn’t. Instead, speculative capital flooded the space and, in many cases, distorted the fundamentals. Startups could raise money during boom cycles, and that fundraising alone was often treated as validation that they were solving a real problem. But when the time came to prove their value, many just didn’t measure up. That disconnect led to a wave of failures, and in my view, it’s because speculative money outpaced real business logic.

Rhishi Pethe: It’s all about the power law, you make 100 investments, and maybe just a handful deliver those big returns while most fail. So is AgVC really any different from other types of VC? If that’s the case, why do people complain so much about AgVC?

Ben Voss: I agree, it’s similar. But placing bets in AgTech is completely different from investing in consumer goods, electronics, software, or other high-tech sectors. In those spaces, you’re marketing to the world. If you launch a new AI software product in Silicon Valley, there’s a potential global consumer market waiting for it.

But that’s not how agriculture works. You can’t just say, “I’m going to start an agronomy company and reach millions of customers worldwide.” You have to ask: is this for row crops or permanent crops? Are we talking about zero-till farming? What geography are we even targeting? The problem you're solving is usually narrow and deeply contextual.

And once you do land on a real commercial opportunity, it’s usually very specific, often tied to a particular country or a small group of countries. You can't apply the same venture model that says, “I’ll invest in a hundred startups and hope that two become unicorns.” That approach doesn't work in AgTech.

You have to be a specialist. If you’re a VC in this space, you need to be scientifically literate. You have to truly understand what you’re investing in. You can’t just listen to a pitch, you have to dig deeper. You need to know how the solution works, where it can realistically scale, and why a customer or acquirer would pay for it. That’s what smart money looks like in AgTech. The best investors bring in partners and research teams who can evaluate technologies and opportunities with that level of depth and clarity.

Rhishi Pethe: It’s tough to find cross-cutting technologies. With equipment, it often has to be tailored to specific crops or regions, because of all the variation. But if you do find one, it could become something really big.

Ben Voss: I think equipment, especially tractors, is a bit different. You can break a tractor down to the basics: four wheels, an engine, a transmission, some hydraulics. Those components are fairly universal worldwide. The only things that really vary are horsepower, technology levels, and complexity. So tractors are one of the few categories that actually work on a global scale.

But when you get into more specialized equipment, like planting, it’s a different story. Take Precision Planting as a case study, they make row crop planters that were specifically designed for the U.S. market. Do they work in other countries? Sure. Some farmers in Brazil, Australia, and parts of Europe have adopted the technology.

But it’s still mostly used in the U.S., because the features, the benefits, and the entire business case were tailored to American farming conditions. The same conditions, and especially the same economics, don’t apply everywhere else. So the benefits don’t always translate.

You have to understand the differences, region by region, crop by crop, economics included.

Thin markets in commodity row crops

Rhishi Pethe: We often refer to these as thin markets. On one side, you have very few suppliers offering technology or solutions. And on the other, even if you add up all the commodity row crop farmers in the U.S. and Canada, you’re still looking at only around 150,000 to 200,000 buyers. So it’s a small group selling to a small group.

That dynamic makes it really hard to achieve the kind of economies of scale you see in internet or software businesses, and that’s a big structural challenge in this space.

Ben Voss: I served on the board of our local phone company, SaskTel, back in the early 2000s, right as cellular technology was taking off. We had about 400,000 subscribers, and we felt pretty good about that. So we walked into Samsung to negotiate a wholesale phone deal.

Their executives asked, “How many subscribers do you have?” We said, “400,000.” They just got up and left the room. A different team came in and said, “That’s how many we sell per day in India.” It was a completely different league, and that’s kind of what agriculture feels like sometimes.

People say there are about 150,000 farmers, but here’s the thing: the number of people who are actually buying new equipment is way smaller than that. If you look at how many decision-makers are out there writing the checks for machinery, it’s a tiny group.

Now compare that to the size of the Ag supply chain. Between Ag retailers, dealership staff, and reps from seed and chemical companies, that number multiplies quickly. In fact, the ratio is probably seven or eight to one, for every one farmer writing the check, you’ve got seven or eight people in the value chain selling to or servicing them.

Farmers are increasingly feeling the weight of the entire system on their backs. They’re being asked to get more efficient every year, while the headcount around them keeps growing, and they’re the ones who are supposed to pay for it all. It’s no surprise they’re frustrated.

Rhishi Pethe: You made an interesting point earlier, that companies often respond to what they’re hearing from customers. What mistakes do you think they’re making when they operate that way? How should they approach it differently? And if you were in charge, what decisions would you go back and unwind, based on what you’ve seen over the last few years?

Ben Voss: If I didn’t have to worry about share price or managing shareholder relations, I’d take a completely different approach. That’s a huge constraint for public companies. When you start proposing long-term visionary strategies, even if they’re the right thing to do, you don’t get rewarded. So most companies avoid them.

But without those shackles, I’d start thinking the way infrastructure engineers think. Take a bridge, for example. If you told taxpayers, “We’re going to rebuild this bridge every 20 years,” they’d push back. They’d ask, “Why are we spending $10 million on something that won’t last?” So instead, we design it to last 50, maybe even 100 years. We run proper lifecycle economics: schedule maintenance every five years, plan for longevity, and target a 150- to 200-year lifespan.

Look at the Romans, you can still drive on some of their roads in Italy 2,000 years later. That kind of thinking would be incredible in agriculture. If we’re implementing new technology or equipment, why don’t we design it to last 20 or 30 years, especially since that’s how long farmers are actually using this equipment?

Once we accept that reality, we can start asking better questions. How many units will we sell over the long term? What will parts and service revenue look like? What kind of farming activities will that equipment support over its lifetime? And how do today’s decisions support, or contradict, that longer-term strategy?

Here’s where it gets tricky: what if we’re putting 25% of a machine’s capital cost into tech, software, sensors, electronics, and that tech only lasts 10 years?

Just recently, Nest told me my 10-year-old thermostat had reached end-of-life. They offered a discount to upgrade, but it was clear: the software was done, and the product was going offline.

Now imagine that same dynamic in a tractor, a machine that’s really a computer on wheels. If farmers plan to run it for 30 or 40 years, how will that work when the tech becomes obsolete or unsupported? That’s the question no one seems to want to ask. Or if they have asked it, they’ve kept it out of the spotlight because it’s not a popular topic.

Maybe some companies have started to think about this, maybe they’ve begun exploring how to decouple the tech from the iron, to let the mechanical system continue to function even if the software is obsolete. But for the past 10 years, the dominant narrative has been: take legacy iron, add new tech, and increase the valuation. That’s what the stock market rewards, and so it became the business plan.

But at some point, a smart analyst is going to ask, what happens when the value of your equipment starts to drop because the technology is outdated? What if a machine you sold five years ago is worth less than one you sold ten years ago, just because it has more tech that no longer works? That’s a real risk. And it could hurt sales, undermine brand trust, and damage confidence in your strategy.

We’re already seeing early signs of this in other industries.

Look at the Cybertruck, values are dropping fast. There are lots of reasons for that, but one of them is strategic concern. Confidence has eroded in less than a year. It takes ten years to build that kind of trust, and twenty minutes to lose it. Companies need to be very careful about that.

Lifecycle expectations for hardware and software

Rhishi Pethe: You're more willing to replace something that costs $250 Canadian. Think about how iPhones evolved: when they first came out, both the hardware and software were advancing so quickly that Apple locked people into an annual upgrade cycle. You'd get a new phone every year, and no one really worried about what to do with the old one, that was a problem for later.

But it’s completely different with Ag equipment. You're talking about machines that last 30 or 40 years. Take a pivot irrigation system, it barely moves, but it can sit in the field for decades. So how should we think about that difference?

On one end, you've got something like a bridge, designed to last 2,000 years. On the other hand, you've got your iPhone, which you might replace every few years, or even more often.

What do we think about this spectrum? What’s the framework? What helps us decide where a product sits on that spectrum, and how often we should redesign, replace, or upgrade it?

Ben Voss: This really gets into the concept of lifecycle economics. It’s about applying financial thinking to every aspect of equipment ownership.

First, you buy the machine, that’s one cost. Then you add fuel, oil, parts, labor. You get a certain amount of productive use out of it, and you ask: what’s my cost per unit of work over time?

And then there’s the question of what you plan to do with the equipment. Am I going to use it until it’s completely worn out and recycled, like I did with my Nest thermostat? Or am I planning to sell it partway through its life?

In farming, we’ve trained the market to expect resale value. It’s a huge factor in purchase decisions. When someone buys new equipment, they do it with confidence that they’ll be able to resell it for good value down the line.

That’s very different from how people treat a smartphone or a thermostat, where obsolescence is expected and built in. Farmers aren’t ready to toss out millions in capital just because some electronics went out of date.

Buying farm equipment is more like buying a house. You don’t look at it as a daily cost of living, you look at resale value. You expect to get something back. That mindset is baked into the industry.

We haven’t crossed into a world of engineered obsolescence in agriculture yet, and farmers don’t want to. Just like how old washing machines from the ’80s and ’90s are now popular again because they last forever and are easy to fix. Meanwhile, the new ones break down in 10 years and can’t be repaired. Whether that’s perception or reality, the belief is strong: older machines were built to last.

That same expectation applies to farm equipment. Farmers believe it should be maintainable, repairable, and operable for decades. And just like used cars, these machines often change hands two, three, even four times before heading to the scrap yard. The entire system assumes longevity, not disposability.

Rhishi Pethe: We’re really talking about two components. One is the hardware, the steel. And the other is the electronics and digital layer. The steel lasts a long time.

The digital side, though, the sensors, software, electronics, that’s evolving fast. Every few years, we see big improvements: better performance, lower cost, more features. But when you combine these two components, there’s a mismatch in expectations.

People expect the full system to last as long as the steel. But the digital part becomes obsolete much quicker, and that’s what these companies are now trying to push: constant digital upgrades.

How do we design systems, or business models, that respect the long lifespan of hardware while still allowing for the rapid evolution of software and electronics?

Ben Voss: 20 years ago, almost all farm technology was retrofitted. If you wanted to add a GPS steering system to a tractor, it didn’t come from the factory, your dealer installed it. It was just as easy to remove as it was to install, and you could still drive the tractor like normal without it.

That retrofit model shaped the foundation of Agtech adoption. Farmers saw that steering systems would only last five to ten years, and that was fine, they only cost around $5,000. You could budget for a replacement every few years without much concern.

But over time, things evolved. Farmers started wanting more: a tablet display, an onboard computer, edge computing capabilities, automation. They wanted sensor networks, machines that could make decisions, and less reliance on human labor.

As engineers looked at that growing list of requirements, they realized it would be much easier to handle it all at the factory. So they started integrating everything, the transmission, the engine, the control systems, into a unified architecture. It became more elegant and seamless, like a modern vehicle. You don’t retrofit a dashboard screen into a new car; it’s built in from day one.

But now we’re hitting the limitations of that approach. What happens in ten years when the software or tech is outdated? Can you rip out the wiring harness, the ECUs, and the sensors and swap in a new system? Not easily, and usually not at all.

And when manufacturers design the next generation of tractors, they don’t design it to be backward-compatible with older models. Those old machines have different specs, different capabilities, it’s easier to focus on selling new units.

But here’s where things get dicey: more and more farmers are starting to worry. They’re asking, “What if I can’t resell this machine in 10 years?” If they can’t get a straight answer, they’re starting to hesitate, and that’s where we are now. That shift in sentiment is beginning to show up.

Rhishi Pethe: It feels like there was a moment, when OEMs made a strategic decision that seemed totally reasonable at the time. From an engineering standpoint, it was easier to bundle hardware and software into a tightly integrated system. And you see this same debate play out between Apple and Android. Steve Jobs famously believed that the people who build great software should also design the hardware, he was all about delivering a unified experience.

Hardware may last decades, but the software and electronics won’t. And by tightly coupling the two, you’re building in a structural mismatch.

Are we conflating the drop in sales with this so-called time bomb? Could it just be part of the broader Ag downcycle? How do we actually separate the two and know what’s really driving the slowdown?

Ben Voss: That’s the big question everyone’s asking. People say it’s just because of low grain prices, and yes, that’s definitely part of it. But when you look at the current environment, I’ve never seen sales drop this sharply during a downturn without more alarm. Something deeper is going on.

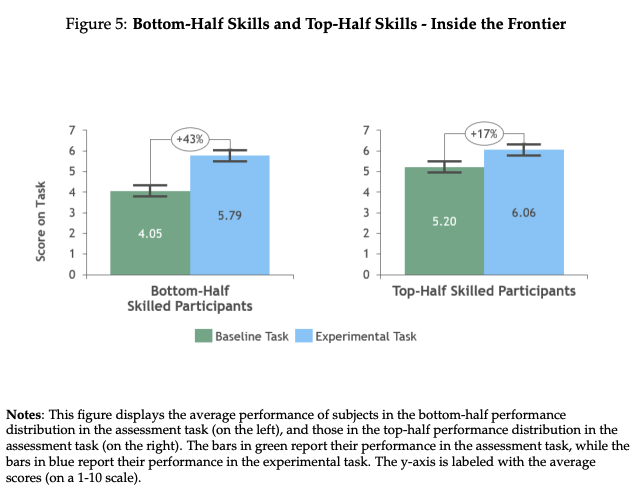

I believe many companies anticipated these results and baked them into their financials a while ago. But even so, you can’t ignore the fact that this cycle is fundamentally different in at least three major ways.

First, we’re seeing large farms trade in massive amounts of nearly new equipment, machines that are just one or two years old. That’s putting huge pressure on the secondary market, which now has fewer buyers and more supply.

Second, equipment prices have skyrocketed, largely due to the technology component. And the used market has caught on. Buyers are paying significantly less for machines that were once expected to hold value. If you took a 2017 combine and added the latest tech and features, plus inflation, the price jump looks enormous.

And that brings us to the third factor: compounding price increases. During COVID, tier-one manufacturers issued quarterly price hikes, often double-digit increases, quarter after quarter. And each one compounded on the last. Demand was strong and supply was tight, people kept buying, so the prices kept climbing.

But now we’ve hit the downturn, and no one has adjusted those prices back down. If we had followed a more conventional pricing pattern, we’d be seeing modest increases of 3–4% per year since 2017. Instead, we saw a massive jump. Now the market is reacting. Basic supply and demand economics are kicking in, and values are correcting harder than anyone expected.

And then there’s the technology risk. It’s now a huge portion of the equipment’s value, and buyers aren’t sure who should be responsible for that risk. Right now, they’re saying, “Not me.” They’re pushing it back to the OEMs or the dealers. They’re thinking, “In five years, this tech will be outdated. I don’t want to absorb that loss.”

So now you’ve got a 2020 combine that might be hard to sell in 2030, not because it can’t harvest, but because its tech is obsolete. And if that tech is deeply embedded, how do you keep it running? Will it still receive software updates? Will it still connect to networks, especially if cellular gets phased out for low-earth orbit systems? What if it's no longer considered secure?

There are dozens, maybe hundreds, of these questions. Farmers have been trusting the system. But now, they’re seeing signs that maybe that trust was misplaced. And they’re pulling back. They’re saying, “I’m not going to buy until I know you won’t leave me holding the bag.”

This isn’t just a simple market hiccup. It’s a complex, diverse set of structural issues. And we need to explain it clearly, rationally. But here’s the difference: I’m talking about it publicly.

Looking for financial multiples

Rhishi Pethe: You worked at Raven and spent time with CNH, and you’ve collaborated with other OEMs as well. So what kinds of internal conversations are they having around this issue?

We talked about Deere taking more of an Apple-like approach, while other OEMs may be less integrated.

But I’ve heard something interesting from several non-Deere OEMs. They’ve said, 'Look, Deere gets a premium multiple on their stock price because of their tech stack. We don’t, so we need to own more of the technology to get that same valuation.”

Are these companies chasing tech ownership purely for market optics and valuation, or do they have a strategic vision that really supports it?

Ben Voss: There’s a powerful narrative behind all of this, and I think it traces back to the way Steve Jobs launched Apple products. He’d walk onstage, build anticipation, and then say, “One more thing…” And when he revealed the product, the crowd went wild. It felt like he could see into the future, like he knew what consumers wanted before they did. The reaction was massive, and the sales followed. It became a predictable pattern, and from an investor’s perspective, that predictability was gold.

That model shaped how people thought about tech investment: if you could deliver innovation with confidence and vision, the market would reward you. And then along comes John Deere, making huge technology investments and major acquisitions. The stock market responded, this looked like the future of farming.

The fundamentals seemed to support it. Farms were getting bigger. Farmers were getting older. There were fewer of them. So, naturally, the answer seemed to be more technology. Everyone nodded. No one really questioned it.

So the Deere strategy, tying cutting-edge tech to an industry in transition, looked like Apple’s. It made sense to follow that narrative. And to be clear, I’m not saying it was dishonest or misleading. It wasn’t. But I don’t think anyone really stepped back and said: Hold on, this isn’t a consumer product story. This is farming. And the business model is completely different.

Imagine if Steve Jobs had launched the first iPhone and said, “This will cost $40,000. I have a group of millionaires ready to buy it, and next year they’ll resell it for $30,000 to the next tier of aspiring millionaires.” The stock market wouldn’t have known what to do with that.

But in agriculture, that’s essentially what we’re asking people to believe. We’re selling a $1 million combine, where a quarter of the cost is software and electronics. And we’re expecting the original buyer to resell it in three years for close to what they paid, because there’s a second-tier buyer waiting, who thinks they can sell it again in five to seven years for $600,000 or $700,000.

That resale chain is what justifies the original purchase. If that chain breaks, if the value doesn’t hold, the whole equation starts to fall apart.

Rhishi Pethe: So product design decisions have to align with the customer lifecycle, the buying cycle, and the resale cycle, right?

Do you see any of the OEMs today thinking this way? Are they designing products with those cycles in mind?

Ben Voss: I think it comes down to this: when you’re inside a publicly traded company and the stock price goes up, you treat that as positive affirmation. The reaction is, “Let’s keep doing what we’re doing, clearly, it’s working.” No one questions the strategy when sales are rising and the market’s rewarding you. That momentum becomes its own justification.

But when sales start to decline, even slightly, the instinct is to manage the narrative, to keep telling the market the strategy is still sound, just with different messaging. You say, “This is just a temporary dip,” or “It’s market conditions,” and you keep pushing forward.

However, if sales keep dropping, quarter after quarter, you eventually have to stop and ask: When is the right moment to re-evaluate? Is this really just the market cycle, or is something more fundamental breaking down?

Fast forward three years, maybe we’ll look back and say, “Remember when we thought something was off? Look at sales now, they bounced right back.” That’s entirely possible. People may keep spending without realizing that the equipment they’re buying today might not hold the value or utility they expect it to in a few years.

That’s one of the challenges in agriculture: sometimes, farmers just like to buy new equipment. There’s no question about that. I often use this example, it’s popular for farmers to own brand-new skid steers. So I ask, “How many hours a year do you use it?” The answer? “Maybe 43.”

“What do you use it for?” “Spreading gravel. Clearing snow. Loading pallets. My wife needed some dirt moved, it was perfect.” “How much did it cost?” “$48,000.”

So they’re spending thousands of dollars per hour of use. But they’ll say, “I could afford it, so I bought it.” That’s not a business decision, that’s a recreational one. It’s like buying a boat, a cottage, or a sports car. There’s no ROI calculation there.

Now apply that to a brand-new tractor loaded with all the latest features. If you know the risks, that it might not hold value or the tech might become obsolete, and you still want it because you have the money and want the experience, fine. That’s a lifestyle choice.

But if you’re making that decision based on cost per hour, cost per acre, return on investment, then it’s a business decision. That’s what professional farmers care about. And that segment of the market is growing fast. These farms are financially driven, data-informed, and highly strategic.

Three years ago, when Deere offered guaranteed trade-in values on combines, those farms jumped in, it was a smart business move. But now that Deere isn’t offering the same guarantees, they’re saying, “Okay, then I’m not buying.”

That’s the shift. The emotional buyers might still be there, but the financial ones are starting to pause, and they’re the ones who drive volume.

Rhishi Pethe: There is a narrative that Deere is more customer-centered, more customer-driven, more tech-forward. They show up at CES, they lead the headlines, and then there’s everyone else. What’s your take on that perception?

Ben Voss: I think that’s a fair assessment for the Corn Belt in the United States. John Deere dominates that region. They hold the largest market share, and they’ve earned it. Deere is an exceptionally well-run company. Their dealer presence is outstanding, and they’ve built what is probably the strongest dealer distribution network in North America, no question about it.

But then you go to Germany. Fendt dominates there. They’ve done an equally good job in that market, and John Deere is actually in third place. So the question becomes: why hasn’t Deere replicated its U.S. dominance in Europe? Is it the product? The distribution? Something else?

Now look at South America, CNH leads the market down there. Again, the key factor is distribution. Dealer strength is everything in this business. Wherever you have high-performing dealers, you gain market share. It’s that simple.

As a customer, I might be loyal to a brand like John Deere. But that loyalty is tied to an experience, a pattern of reliability, confidence in service, and parts availability. That translates into strong resale value. When I buy a new machine, I know there’s a market for it down the line. People trust the brand, so they’ll buy it used. That gives me confidence.

Designing for obsolescence curves

Rhishi Pethe: The obsolescence curves are totally different: the digital side becomes outdated quickly, while the steel holds value and functionality for decades. How do we design differently to reflect those diverging lifespans? How do we rethink the sales model?

Ben Voss: I’d encourage everyone in the industry to seriously consider decoupling technology from machine integration. There’s real value in offering two distinct experiences:

First, a fully integrated, seamless system, something modern, elegant, and trouble-free. One that dealers find easy to support, and one that offers a cohesive technology ecosystem from planting all the way to visualization. That’s what every major player, John Deere, CNH, AGCO, is moving toward. Their roadmaps point to that unified customer experience. And it’s what most of us, frankly, want.

But I’d suggest we pause and rethink the level of integration. Why not also build in a fallback mode, a way to strip the tech off and leave behind a fully functional, manually operable machine? That kind of redundancy adds enormous long-term value.

Take a 4WD, 800-horsepower tractor as an example. In its primary use case, it’s a powerful farm machine. But tractors like that can also serve other industries, construction, mining, infrastructure, where buyers don’t necessarily want high-end Agtech. They just want an engine, tires, a hitch, and reliable mechanical performance.

If we design these machines so the software can be removed or bypassed, and the tractor still runs, that opens the door to secondary markets. And it gives the original buyer more confidence in the machine’s residual value. But when we make everything so tightly integrated and specific to one use case, we close that door. A construction company isn’t going to buy a machine that constantly needs software updates or dies in the field because of a tech glitch it can’t diagnose.

Imagine instead being able to tell that buyer, “We removed all the proprietary tech. The engine still starts. The transmission still shifts. The machine drives. You can run it with a summer student and a wrench.” That’s a feature, a real selling point. And it’s one I don’t hear anyone talking about.

If I were roadmapping equipment today, I’d prioritize asking, how do we design an electronically controlled transmission that still functions when disconnected from the cloud? Can we operate this machine without an Ops Center, without lockouts, and without relying on continuous connectivity?

This ties directly into the right-to-repair conversation too. If we give secondary owners the ability to strip away unsupported tech and still run the core machine, we preserve value, and we build trust.

Look at the car industry. The aftermarket parts and modifications market is massive, as big as the car industry itself. You can buy a $5,000 used car and throw $10,000 of custom parts on it. Why? Because the platform is open and flexible.

We need that same thinking in Ag equipment. If we embrace modularity and flexibility, the whole market becomes more rational. The primary buyer, the tech-forward, professional operator, can say, “I’ll use this equipment during the high-value, tech-supported phase.” Maybe that’s five years. After that, they depreciate the tech, strip it off, and sell the base machine to someone who wants a reliable, no-frills tractor.

That second owner can use it until the machine’s end-of-life, for planting, harvesting, or even in a non-ag application. It’s not about whether the software still works. It’s about whether the engine turns over and the wheels roll.

Rhishi Pethe: You start with a $1 million machine, pull out $200k worth of software and electronics, and now you’ve got an $800k machine that’s still viable. You depreciate accordingly, and the math kind of works out.

There’s another potential path I’d love your take on. What if, instead of focusing on building one $1 million autonomous machine, we shift toward a fleet of $100,000 machines that are smaller, more responsive, and maybe semi-autonomous? They’d live in the field, work more flexibly, and you’d replace one every few years. You shift the price point, treat them as a fleet, and build in natural refresh cycles.

And here’s a second idea: what role could open source play? Imagine a company that specializes in upgrading the digital components on older equipment, stripping out the outdated tech and dropping in new hardware and software, while keeping the core machine.

Ben Voss: There’s a big discussion in the market right now about whether we could build smaller, less expensive, more automated machines, and whether that would actually work. I think it could, but not if we’re talking about microbots running around in cornfields. That’s not realistic.

What I’m imagining is something more grounded. Let’s say I’m a highly trained, professional machinery operator, someone who knows how to optimize equipment performance across multiple functions, whether it’s planting, spraying, or harvesting. I’ve mastered the displays, the interfaces, and the systems.

Now imagine instead of hiring five operators to each run a separate combine or sprayer, I control all five machines. They’re smaller, semi-autonomous units, maybe not one-tenth the size of a traditional machine, but maybe half. Instead of running a 600-horsepower tractor, I manage two 400-horsepower ones operating in tandem. I'm in one of them, right there in the field, supervising and coordinating the rest.

This setup increases my productivity without going bigger, it just goes smarter. I’m not sitting at a desk miles away; I’m in the cab, with real-time visibility and control. And if something breaks down or the automation fails, I send someone over to take manual control. The machine still has a cab, a steering wheel, and basic controls. We don’t lose functionality, we just shift between modes.

That’s the future I think many farmers are ready for. Tech-savvy operators can support this kind of ecosystem. They’re capable of troubleshooting internet outages, monitoring system behavior, and overseeing fleets of machines with growing confidence. And over time, as the technology becomes more reliable, their confidence will grow even more.

But here’s the crucial piece: after the subscriptions expire, after the software stops getting updates, and when the ECUs age out and no one builds parts for them anymore, the core machine still works. The engine starts. The transmission shifts. The wheels turn. And there's another farmer, maybe on a smaller operation, who says, “I don’t need all the tech. I just want to get the job done.” And they buy that used tractor or combine, and keep using it.

Because not every farmer is part of a 20,000-acre consolidated operation. There will always be smaller farms. A 400-horsepower tractor might be overkill for one, but in a post-tech resale market, it becomes a perfect match. And when the equipment is built to allow manual fallback, it lives a second life, and continues creating value.

This kind of autonomy, where one operator can manage a fleet, makes real sense to me. And so does the idea of modular systems that allow tech to be removed when it’s no longer viable. I know these are philosophical positions. Maybe they’re not mainstream yet. But I’ve talked to a lot of farmers who nod their heads when I bring this up. It resonates.

Meanwhile, manufacturers are still focused on “bigger and better.” It’s like a race car team, always building the next more powerful, faster machine to win the race. And sure, that gets attention. The headlines always read: “Biggest tractor in the world!” or “Most powerful combine ever!”

Rhishi Pethe: A small number of farmers work the majority of the acres. There’s a steep drop from the top tier to the second, and an even steeper drop to the third.

But there are still a lot of farmers in those second and third tiers. So take the example of a 400-horsepower combine, for many of those farmers, that’s just too big.

What if instead of a 400-horsepower combine, we built a 100-horsepower version? Smaller, more accessible machines could serve a broader base of farmers. And if we could decouple the tech stack from the iron, make it modular, we might extend how often that machine can be resold and upgraded, not just reused.

Could that unlock new value at the mid and lower tiers of the market? And could it support a more distributed, longer-lived equipment ecosystem?

Ben Voss: I’ve spoken with people in product management, especially around combines, who’ve admitted: “We may have built a combine that’s just too big. There may not be a second or third owner for this machine.” But they felt forced to build it anyway, because everyone else was doing it.

But manufacturers respond to sales. If farmers start saying, “Actually, I prefer this mid-size version,” then companies will pivot. If the biggest machines don’t sell, and the smaller, smarter ones do, the OEMs will follow the demand. That’s how the market works, and always has.

Companies like Raven, Trimble, and Topcon built their businesses on aftermarket add-ons and tech integrations. They enabled farmers to upgrade existing equipment with new capabilities. That model empowered flexibility, affordability, and innovation.

But most of those companies have now been acquired and absorbed by larger OEMs. With that shift comes pressure to serve the parent company's strategic interests. So instead of building universally compatible tools, they’re incentivized to optimize only within their own brand ecosystems. As a result, we’ve seen a steep decline in retrofit innovation, and we probably need more of it now, not less.

If I were advising CNH, AGCO, or any other major player, I’d tell them this: the next competitive advantage lies in offering an open, collaborative ecosystem. The winning OEM will be the one that supports smaller manufacturers, tier-two OEMs, and retrofit innovators, not just tolerating them, but actively partnering with them.

You need to use the tech ecosystem as a sales tool, not a barrier to create a seamless end-to-end experience that encourages customers to buy your brand across the whole farm. That’s part of the playbook John Deere has used effectively with the Operations Center. You also need to recognize you don’t build everything, but it can work with other pieces. Farmers want flexibility. They are asking “Why can’t your tractor work better with this cart or this retrofit kit?” They’re not demanding a completely open-source world, but they do want interoperability and a basic level of tech neutrality.

Don’t force integration for the sake of control. Some OEMs treat their tech stack as a moat, blocking third parties to keep customers inside their ecosystem. That works, until it doesn’t. As soon as your system fails to deliver what farmers actually need, they’ll abandon it. And they’ll do it quickly.

We’re already seeing that behavior in planter technology. Farmers routinely rip brand-new Deere planter units off and replace them with Precision Planting hardware. Why? Because even though Precision’s system doesn’t integrate cleanly with Deere’s Operations Center, the tech is better, and that matters more.

So the next major competitive edge in Agequipment isn’t just about building bigger or smarter machines. It’s about collaboration, flexibility, and modularity.

That’s the mission I’m working on now, building a path for innovation, retrofitting, and open collaboration between major OEMs and independent players. Not to compete with them, but to extend the value of what already exists. Think of it like the early days of the internet. Eventually, phone companies realized they had to adopt common standards, or be left behind.

Rhishi Pethe: Everybody wants to be like Deere. What kind of decisions does it lead down to which are not in your best interest?

Ben Voss: This is one of the most controversial topics in the farm equipment industry, because the moment you say it, you're effectively saying John Deere leads. And in the U.S. Midwest Corn Belt, they absolutely do. But on a global scale? Not so much. You really have to go country by country to understand who’s dominating and why.

Take Germany: Fendt leads the market there. Why? Because Fendt tractors are superior in a dozen ways. AGCO bought Fendt and did a great job maintaining and building on that legacy. Or take India, Mahindra dominates. Each region has its own leader for specific, valid reasons.

In North America, Deere’s dominance comes from two key things: the Operations Center and their dealer network. Their technology platform and dealer distribution are second to none here. That’s what pushed them to the top.

Now, plenty of people will tell you Deere’s engines aren’t the most reliable, their fuel efficiency isn’t the best, and their combines are probably third place in terms of actual harvest performance. But it doesn’t matter, because what they offer is resale confidence. That’s why they dominate.

So when other companies try to copy Deere’s strategy, they need to ask themselves: Are we copying the technology roadmap because we truly believe our tech will lead? Or are we doing it because we think resale value will follow?

Most don’t ask that question. They just assume it’s a tech race and say, “Let’s dominate technology.”

But if your sales and market share don’t reflect that, then you have to dig deeper. Is the issue really your tech? Or is it something else, like a weaker dealer experience? Maybe your hydraulics underperform. Maybe your transmission fails too often. It’s hard to isolate a single reason, and that’s what confuses people about what’s actually driving success.

Still, Deere pulled ahead because they made bold moves 20 years ago when no one else would. They started acquiring tech companies and building their own stack. That gave them a massive edge.

A mentor once explained it to me this way: If you want to win the Super Bowl, you can’t rent the stadium, hire contractors as coaches, and borrow all your players from other teams. You’ve got to own the stadium, the coaches, the players. That’s exactly what John Deere did. They invested in ownership, and the market rewarded them with higher sales and a stronger stock price.

What's next?

Rhishi Pethe: Finally, what are you working on right now?

Ben Voss: The reality is, there are only a few companies left in the AgTech space that still offer true innovation and are building amazing technology for agriculture. And today, if you want to deliver high-end automation for farm equipment, there are minimum capabilities you simply have to bring to the table.

You can’t just “grad hack” your way through anymore. You need to be able to build ECUs, implement edge computing, ensure robust communication infrastructure, and have deep engineering experience. None of that happens overnight, it’s incredibly hard to build and very expensive to scale.

That’s why I believe the companies that have been playing around the edges of the market should now be invited to step into the core and start scaling off their existing base. So I chose to partner with Calian for a reason: they operate one of the largest electronics manufacturing facilities in North America, building rugged, high-end electronics. They’ve got GNSS capabilities, manufacture their own antennas domestically, and run a large engineering team that works on advanced military and satellite systems.

That kind of core competency can absolutely be applied to agriculture, especially when paired with other companies that already have a catalog of farm equipment or componentry that’s well suited to this space, but are missing some critical pieces. If we can connect those dots, we can offer what Trimble, Topcon, and Raven used to: a full-stack retrofittable automation solution.

Because the truth is, those three players, who led the retrofit space for over two decades, have largely stepped back. So if you're a farm equipment OEM today and you want to add automation, where do you go? It's tough to find the right service provider with the right components and expertise to fill that need.

That vacuum is real. And my goal is to help build the right partnerships, with companies that each bring a vital piece of the equation.

Rhishi Pethe: And you’d want to design it with that loose coupling approach you mentioned earlier? So you can swap out the tech, upgrade it, or even remove it entirely, and the core machine still works.

Ben Voss: I’d love to approach this the open-source way, that model just makes sense. But I get it: in some cases, R&D budgets are directly tied to IP protection. It’s tough to justify developing a highly advanced sensor only to say, “It’s free for anyone to use.” That tension is real.

That said, a lot of the foundational technologies we’re talking about aren’t bleeding edge anymore, they’re mature, proven, and ready to scale. If someone told me they had a farm implement that needs hydraulic control and a ruggedized edge computing unit? That’s not an exotic request. Those components are out there. We can integrate them. We can adapt.

And honestly, that’s the new baseline. In today’s market, the conventional farm equipment industry expects a certain level of automation as table stakes. Whether it’s planting, spraying, or even something like manure spreading on a dairy farm, people expect the machine to have variable rate capability, GPS mapping, and the ability to follow a prescription map.

Five years ago, those features were optional. Today, you can’t even compete without them.

Rhishi Pethe: You’d want to use off-the shelf components that are readily available and easy to integrate.

Ben Voss: combination of that and also the ability for teams to coalesce around the customer problems and be like, we're going to rapidly innovate something new here, but doing it in a partnership model. It's like a teaming agreement is kind of the way I look at it, where you say, you've got this, I got that, let's put it together and that solves the problem for the customer.

But sometimes you just need some core infrastructure. I have a football stadium. I need a few players to come and win some games with me, right?

Other relevant articles

- An Innovator’s Dilemma in the Field: How Autonomy is Forcing OEMs to Rethink Big Iron by Patrick Honcoop (LinkedIn article on June 11, 2025)

- SFTW article: Is the future of farm equipment smaller? (May 25, 2025)

- SFTW article: Second order effects (April 20, 2025)

- SFTW convo: Guy Coleman: From Danish pastries to precision weeding (June 4, 2025)