Farming the Microbiome: How Soil Management Shapes Life Underground

Tuesdays with Dr. Tuesday

I am excited to welcome back Dr. Tuesday Simmons for the fourth "Tuesdays with Dr. Tuesday" monthly issue. Over the next few months, Dr. Simmons will share her perspective on the importance of the soil microbiome to agriculture and the development of new technologies.

You can read her full bio at the end of this post.

So far in this blog series, we’ve discussed basics of the soil microbiome, how plants interact with soil microbes, and the complexities of soil health. So how does this all connect with the practicalities of farming today? Farmers may recognize the importance of the soil microbiome, but it’s crucial for researchers and extension specialists to share new data on how farming practices can impact their underground allies.

In this article, we’ll dig into (no, I won’t stop using that pun) the impact of different management strategies (including tillage, cover cropping, crop rotation, and application of inputs) on the soil microbiome.

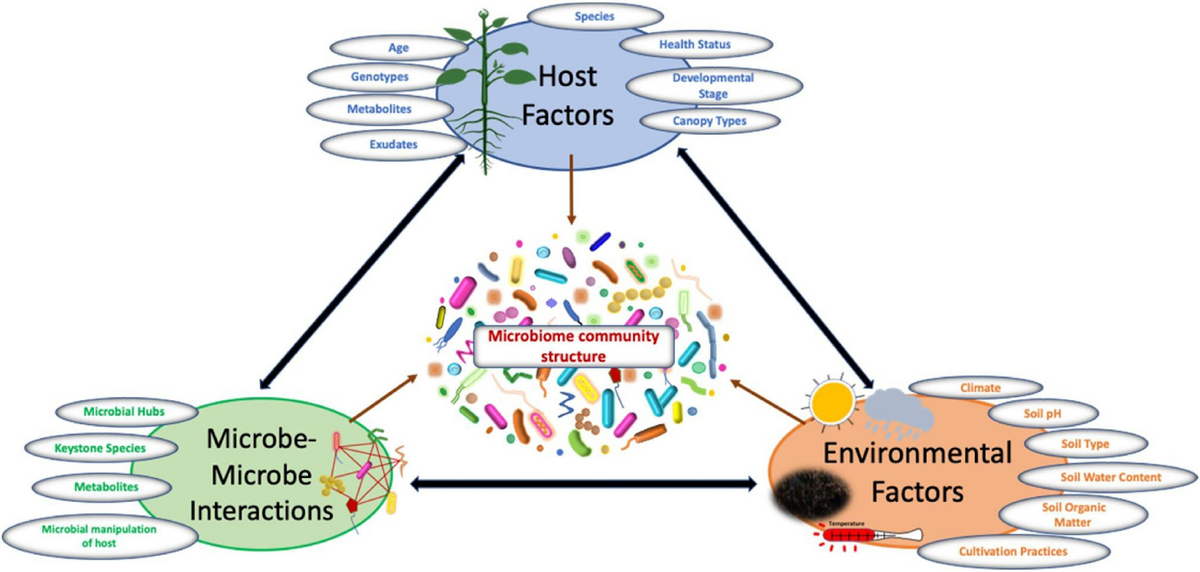

What “drives” the soil microbiome?

As soil microbiologists have sought to understand this “final frontier”, a major area of research is determining what variables might influence (or “drive”) the soil microbiome. For instance, in my PhD research, I investigated how drought can be a driver, pushing microbial communities in a specific direction.

The major drivers of the soil microbiome are: pH, climate, and organic carbon.

Not surprisingly, when you add in the complexity of crops growing in the soil and farmers cultivating them, there are a lot more variables that can drive the microbiome, primarily crop species and age (2).

Soil microbiologists have been working to understand the impact that farming practices have on microbial communities, and I’ve summarized some of their research here.

If you’re curious about how scientists determine what microbes are present in a soil, refer back to the first post in this series: Soil Microbes are Feeding the World.

Physical impacts: tillage

Like the other farming practices I’ll talk about, there are other resources that discuss the broader impact of tillage on soil quality, so here I’ll focus on the impacts to soil microbes.

Scientists have found that using conservation tillage practices increased soil carbon (total, active, and microbial biomass), but there’s no difference in microbial biodiversity between tilling and no-till systems (3). Despite no change in diversity, there are some differences in the types of microbes growing in the two different soils: nitrogen fixers are more abundant in no-till soils (3).

There is some evidence that a reduced tilling practice results in the most stable microbial communities over no-till or conventional till practices (4). A more stable microbiome can be beneficial because it resists the invasion of pathogens as well as bounces back more easily from disturbance.

Cover cropping

Benefits of using cover crops include: reduced soil erosion, improving soil quality, sequestering carbon and other nutrients, and controlling weeds and pests (5). But how does growing cover crops impact the soil microbial community?

- Increases microbial abundance, activity, and diversity (6)

- Enhances “multifunctionality” (microbes that improve nutrient storage, nutrient cycling, and organic matter decomposition) (7)

- Increases microbial production of phytohormones auxin and gibberellin (8)

- Increases the stability of microbial communities (7)

Crop rotation

Understanding the impact of crop rotation on the soil microbiome can be difficult, because the type of crop planted has a major effect on its own, but soil scientists are no strangers to complexity!

While rotating crops does not have an impact on the diversity of bacteria in the soil, it does significantly increase fungal richness (number of species) and diversity (9). Soils under crop rotation also have more complex and more stable microbial communities (9).

Farmers won’t be surprised to hear that there are fewer pathogens in the soil when they rotate crops, though they might be pleasantly surprised to hear there are also more nitrogen cycling microbes (9).

Applying soil inputs

“Soil inputs” is an incredibly broad category, so I’ll be breaking it down into two still-broad-but-slightly-smaller categories: fertilizers and pesticides.

Fertilizers

Application of either manure or mineral fertilizers can increase soil microbial biomass (10, 11). Manure also increases the diversity of bacteria while reducing fungal diversity (10), and mineral fertilizers increase soil organic carbon (11).

Long-term fertilizer use can impact pH, which significantly affects soil bacteria (12). Additionally, extended fertilizer applications can increase seasonal variation in microbial communities and make communities less stable (13).

Pesticides

These substances vary widely in their composition, targets, and mode of actions, and the effects on the soil microbiome should be studied individually. However, there is a recent study that looked generally at pesticide residues and found that they increased fungal diversity and abundance while decreasing bacterial diversity and nitrogen fixation (14).

Key takeaways

- Soil management practices influence not just the physical and chemical properties of soil, but also the composition, stability, and function of the microbial communities that live in the soil.

- Agronomists and researchers can work together to apply these insights, using the management practices that optimize yield while caring for the soil microbiome.

References

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology15, 579–590 (2017).

- Parks, D. Plant Microbiomes. Microbiomes: Health and the Environment https://uta.pressbooks.pub/microbiomeshealthandtheenvironment/chapter/plant-microbiomes/ (2022).

- Horia Domnariu, Trippe, K. M., Botez, F., Partal, E. & Postolache, C. Long-term impact of tillage on microbial communities of an Eastern European Chernozem. Scientific Reports 15, (2025).

- Hu, X. et al. Conventional and conservation tillage practices affect soil microbial co-occurrence patterns and are associated with crop yields. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 319, 107534 (2021).

- Adetunji, A. T., Ncube, B., Mulidzi, R. & Lewu, F. B. Management impact and benefit of cover crops on soil quality: A review. Soil and Tillage Research 204, 104717 (2020).

- Kim, N., Zabaloy, M. C., Guan, K. & Villamil, M. B. Do cover crops benefit soil microbiome? A meta-analysis of current research. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 142, 107701 (2020).

- Guo, Y. et al. Microbial communities mediate the effect of cover cropping on soil ecosystem functions under precipitation reduction in an agroecosystem. Science of The Total Environment 947, 174572 (2024).

- Seitz, V. A. et al. Cover crop root exudates impact soil microbiome functional trajectories in agricultural soils. Microbiome 12, (2024).

- Kong, W., Yao, Y., Qiu, L., Shao, M. & Wei, X. Crop rotation enhances soil microbial network complexity and functionality: a meta-analysis. Applied Soil Ecology 216, 106511 (2025).

- Guo, Z. et al. A global meta-analysis of animal manure application and soil microbial ecology based on random control treatments. PLOS ONE 17, e0262139 (2022).

- Geisseler, D. & Scow, K. M. Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms – A review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 75, 54–63 (2014).

- Ren, N. et al. Effects of Continuous Nitrogen Fertilizer Application on the Diversity and Composition of Rhizosphere Soil Bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology 11, (2020).

- Li, B.-B. et al. Long-term excess nitrogen fertilizer increases sensitivity of soil microbial community to seasonal change revealed by ecological network and metagenome analyses. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 160, 108349 (2021).

- Walder, F. et al. Soil microbiome signatures are associated with pesticide residues in arable landscapes. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 174, 108830 (2022).

Dr. Tuesday Simmons Bio

Dr. Tuesday Simmons earned a PhD in microbiology from the University of California, Berkeley for research into the effects of drought on cereal crop microbiomes. Post-graduate school, she has worked for start-up companies in R&D, sales, and marketing roles with the goal of effectively communicating the value of cutting-edge biotechnology.

As an Application Scientist at Isolation Bio, she worked with leading gut microbiome researchers to improve high-throughput microbial isolation for academic and pharmaceutical purposes. At Root Applied Sciences and Trace Genomics, she has worked to leverage microbiome research for farmers and agronomists. Since 2024, she has worked as a freelance science writer and consultant.