For all that AI, distribution is still king

Innovation adoption is gated by distribution, especially in agriculture

Welcome to the June 15, 2025 edition of SFTW. Happy Fathers Day to everyone.

This week’s edition highlights how distribution is still more important to get right compared to technology, especially when it comes to agriculture. This is not new news or approach, but it needs to be mentioned time and again. These principles apply irrespective of the farming system.

Scaling Regen Ag Starts with Better Data

Farmers Edge is building the digital backbone for regenerative agriculture—designed to simplify Scope 3 reporting and deliver credible results, fast. With Managed Technology Services built for agribusiness, Farmers Edge connects real-time field data to your sustainability goals across every acre and every grower in your network. From in-season tracking to end-of-year proof, Farmers Edge makes regen ag measurable and manageable. If you're serious about scaling impact and reporting, this is the infrastructure that makes it possible.

For all that AI, distribution is still king

I did a keynote (“Is AgTech relevant in 2025?”) talk at the Plug and Play Center AgTech Expo in Sunnyvale, CA on June 11th. Here are the slides from the talk.

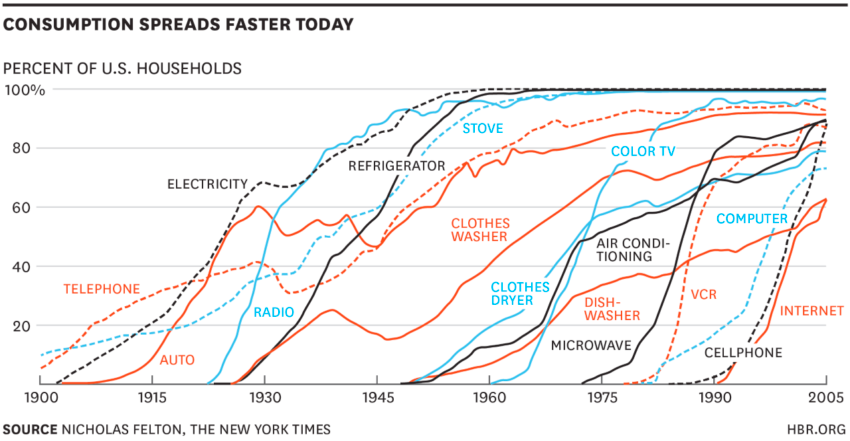

I started the talk by showing some data on timelines on how new technology gets adopted with examples of consumer technology in the US, digital technology, and agriculture technology.

Consumer technology like the telephone took much longer to be adopted by 50% of the US population, compared to the internet.

Among digital technologies, the adoption rate of ChatGPT is not even a curve, but a straight line going up. Adoption of Netflix is a steep curve, but the rate of increase has slowed as more and more people have adopted Netflix.

We saw a similar and rapid adoption rate for physical products like Bt and HT (Herbicide Tolerant) corn, soy, and cotton. 50% of planted acres were on HT soybean just within a few years.

The obvious question then is,

What determines the rate of adoption of a new technology?

At a very high level, there are two main vectors which determine the rate of adoption.

- The product or technology itself, how well does it work, and does it create surplus for the customer / user.

- The distribution mechanism to get the new product or technology in the hands of customers.

The more closely these two vectors are aligned, the faster is the adoption rate of any new technology.

In the case of telephones (which were land line telephones for you young’uns!), a distribution infrastructure of telephone cables, switching systems, and telephone exchanges had to be built before it could get into the hands of the consumers. Building that infrastructure from scratch was expensive and slow. It was primarily the infrastructure which determined the rate of adoption of telephones in the US.

In the case of ChatGPT, the product and technology is amazing, and the distribution infrastructure of smart phones, and the internet is already in place. A great product coupled with great marketing and word of mouth, led to a straight-line-going-up adoption.

In the case of HT and BT seeds, the seed and chemical companies had access to a large distribution network of dealers, seed salesman, and ag retailers, who were motivated to sell the product.

Agriculture’s acute distribution challenge

Agriculture’s distribution challenge is acute.

Across multiple sectors of the industry, a handful of companies control a majority of the distribution network to farmers.

For example, a handful of seed companies, a handful of equipment companies, a handful of off-take companies have a plurality of market share within their sector.

This pattern goes on and on, with some differences based on farming systems and regions.

These entities have trusted and long relationships with the farmers and growers. You must have heard this cliche multiple times that farming is a relationship business. These entities have a stranglehold on those relationships, which is backed by a strong product portfolio and infrastructure built over many decades.

In such an environment, it is very important for startups to focus on distribution from day 1. In fact, I would go so far to say, the distribution aspects are even more important (and difficult) than the technology and the product, when it comes to farmer products. We have many examples of startups failing to scale due to a lack of access to a strong distribution network.

One of the recent examples is Farmwise, which despite having a very versatile and workable product for mechanical weeding, could not find the necessary and effective distribution channels to get their product to a large enough number of customers.

A company like Agtonomy and its founder Tim Bucher, have been very clear from the beginning that they do not wish to go direct-to-farmers to install their automation and autonomy software on existing equipment for specialty crops and vineyards. Tim Bucher wrote the following in October 2024, (highlights by me)

But when I cofounded Agtonomy, focused on developing advanced autonomous software solutions for tractors and implements, I couldn’t help but listen to my farmer sensibility. Would I, as a farmer, trust a piece of equipment from a company called “Agtonomy?” I wouldn’t. Like most farmers, I don’t buy equipment from unknown brands.

Most autonomous solutions available to farmers right now are from startups farmers have never heard of, nor trust. And what machines they do have are available only in very limited numbers.

Farmers don’t have the time to waste on Agtech startups to manufacture machines that take years to deliver and have yet to earn grower’s trust. A more common-sense approach would be to partner directly with established OEMs and IEMs (integrated equipment manufacturers). These collaborations leverage trusted brands and existing dealer networks, ensuring farmers receive reliable, autonomous solutions that seamlessly integrate into their operations and drive profitability.

Agtonomy recently announced a partnership with Kubota, the Japanese small horse power agriculture equipment manufacturer.

Kubota North America is launching a strategic collaboration with Agtonomy, a leader in agricultural autonomy software, to commercialize autonomous operations on Kubota diesel tractors for spraying and mowing.

Agtonomy’s AI-driven automation helps growers tackle labor shortages, improve efficiency, and manage rising costs—embedded at the factory level with the world’s leading equipment brands for operations like mowing, hauling and other repetitive tasks. Agtonomy provides a unified software user experience on top, which can work with a mixed fleet of equipment.

The initial phase of this partnership will focus on integrating Agtonomy's capabilities starting with Kubota's popular M5N diesel tractor, widely utilized among grape, orchard, and similar operations. The phased rollout will be introduced to select growers, coupled with Kubota dealer support to ensure seamless integration into the grower's work loop.

This initiative ensures seamless adoption of autonomous solutions within existing diesel tractor and sprayer operations, minimizing infrastructure demands, such as reducing pesticide use, managing labor shortages, and increased labor costs, while maximizing operational efficiencies for specialty agriculture customers.

For a startup like Agtonomy, it feels like the right strategy to get their products to market faster, and at a lower cost. Agtonomy gets access to Kubota’s brand name, dealer network, and the after-sales service which comes with it. After-sales customer service and support is super important, and it is often very expensive for a startup to spin up. It makes sense to partner with an existing player.

The types of problems Agtonomy can solve, and the customer base in which Kubota operates has a strong synergy. Kubota products get the advantage of bringing autonomy, and remote management through Agtonomy capabilities.

It sounds like a win-win, at least on paper.

Signaling a culture of collaboration and open innovation

Kubota has signaled a culture of collaboration through their open innovation model.

Kubota has and wants to collaborate with partners outside the company, including startups, universities, and research institutes.

Through open innovation, Kubota intends to accelerate smart technologies in crop production and expand operations upstream and downstream in the food value chain, along with realization of an agri-platform as a company responsible for connecting all partners across the chain. In doing so, we contribute to the entire food production system.

Kubota wants to extend their influence beyond their core activities and help create value both upstream and downstream to their existing business areas.

Kubota will proactively utilize the latest technologies, including ICT and AI, to create new value in the fields of food, water, and the environment. In the food sector, we aim to go beyond our existing business domains focused on crop production to provide total solutions that support the food value chain, which encompasses the entire scope of agricultural production from purchasing to processing, sales, and consumption.

Kubota has been quietly building up capabilities in the specialty and tree crop sector, which fits well with their product portfolio.

It is not clear if Kubota has its own venture arm or not. Kubota has not only made investments in AgTech companies, they have been active on the acquisition side with acquisitions of AgJunction in 2021 for about $ 72 million and the acquisition of Bloomfield Robotics in 2024.

AgJunction was a global provider of guidance, autosteering, and autonomy solutions for precision agriculture applications. The company's technology enables precision agriculture practices, which involve using technology to optimize resource use, reduce waste, and increase yields. AgJunction also held 200 steering and machine control patents.

Bloomfield’s service includes an advanced camera, on-farm data processing systems, and a grower dashboard providing real-time plant-level assessments. The service delivers real data that transforms customers’ ability to make accurate projections and yield estimations, guiding decision making around harvest timing and workforce deployment.

The software capabilities from Agtonomy will complement the capabilities acquired through AgJunction and Bloomfield to provide a more compelling autonomy and precision agriculture solution with a layer of software on top for easy management of automation, flexibility and easier customer support.

Regulation still matters

Even though I focused on product / technology and distribution as the two most important vectors for innovation adoption, oftentimes regulation matters. Regulation can hold back innovation adoption for the “greater good” or by being overly protective of things which don’t need protection from state actors.

Many of the regulations and licensing requirements are often a way to protect incumbents and entrench their powers.

For example, hairstylists in California need to be licensed by the California Board of Barbering and Cosmetology to legally perform hairstyling services for a fee. This means they must complete specific training hours, pass a written examination, and obtain a license 🙄. Why does a hairstylist need a certification??

We see the same problem in agriculture.

California farmers are hurting as California continues to ban driverless tractors, and other autonomous robots.

When it comes to farming equipment, an operator must be “stationed” at the controls, according to California safety regulations. Those rules were written nearly 50 years ago, long before autonomous tech was developed. While the original intention wasn’t to ban new technology, that is essentially what has happened.

This is a head scratcher when self-driving provider Waymo has gone from practically zero business to about 27% of the rideshare market in San Francisco in the last 20 months.

Key takeaways

- If you are a startup with farmer produce, the best strategy is to work with a distribution partner or strategics.

- As a startup, think about distribution from Day 1. Access to distribution is more important than your product or technology.

- If you are a strategic incumbent, signal your intention to the market to partner and invest.

- For strategic incumbents, be easy to partner with and clearly state where you need collaboration and how you will support it.

In other news

Small and mid-sized farmers often get the short end of the stick, when it comes to access to new innovation and technology. Many technology providers typically cater to the higher end of the market before they can think about providing products to small and mid-size farmers. AgriERP Lite is a farm management solution which caters to small and mid-size farms with basic features like work order management, yield monitoring, inventory management, and resource allocation.

A bill (AB839) that would streamline the approval process for sustainable aviation fuel projects in California is advancing through the Legislature, drawing both strong industry support and environmental justice opposition.

On the other side in North Dakota, a company called Gevo plans to add a sustainable aviation fuel plant to the corn-based ethanol plant it purchased at Richardton in southwest North Dakota. The Red Trail plant was the first ethanol producer in the country to implement carbon sequestration, capturing carbon dioxide from the plant’s corn fermentation tanks and pumping it into permanent underground storage.

IronConnect, a provider of technology solutions for the heavy equipment industry, has announced the launch of its comprehensive end-to-end platform “DealerFlow” designed specifically for equipment dealers. This powerful new offering combines all the critical tools dealers need to drive more value from their inventory and realize maximum returns from transactions on a single artificial intelligence (AI)-driven platform,

Newly published research shows that AI trained exclusively in a digital twin technology environment using simulated strawberry fields achieved 92% accuracy in detecting fruit, without relying on real-world training data. If this technology works at scale, it could lead to lower development costs as companies can test robotic pickers. The robot trained entirely on synthetic images also estimated real-world fruit diameter with only 1.2 millimeters of error – “good enough for commercial grading, using only synthetic, simulated data,” adds Choi.