Let's be honest about vertical farming

A postmortem of Plenty still misses the point

Welcome to the Sunday edition of “SFTW Plus”.

SFTW Plus is the paid version of “Software is Feeding the World” and includes all Sunday newsletters, SFTW Convos series, Scaling Innovation series, and access to the archives.

The topic of vertical farming came up again this week due to an autopsy for Plenty (not sure how you can call it an autopsy when Plenty is still a going concern, albeit a much smaller one) published by AgFunder News.

My guess is that investors will be left with no clothes but just a big strawberry covering their private parts, when all is said and done about vertical farming. (I tried to generate an image using multiple LLMs, but none of them would generate one based on my prompts!)

Let’s be honest about vertical farming

In January 2025, I wrote about vertical farming in the context of Plenty’s financial and commercial struggles.

My main hypothesis is that vertical farming is not the most suitable solution for the problems vertical farming companies make claims of solving. It showed a lack of first principles thinking, a disregard for customer needs and what will create a differentiated product, and an absence of intellectual honesty about the sector.

The vertical farming space is showing some improvements in their thought process, though based on some latest statements, a lot more needs to happen to right size the opportunity.

As I said in January 2025,

We need to explore better business models to make produce more easily available to a large set of customers at affordable prices, while it being profitable for the grower / supplier and the grocery retailer.

We need to think about growing food as a growing food business, where technology is an enabler. Many of the vertical farming companies have labeled themselves as technology companies who do farming, rather than the other way around. This has created mismatched expectations on value creation, timeline to profitability, multiples, and the type of investor they have attracted.

Vertical farms must strike a balance between leveraging technology and adhering to agricultural best practices to ensure successful operations. Rather than obsessing over becoming the next cutting-edge farming technology stack, vertical farms should prioritize their products, customers, branding, marketing, distribution, and operations. Resolving this identity crisis requires effective messaging from leadership to investors and team members.

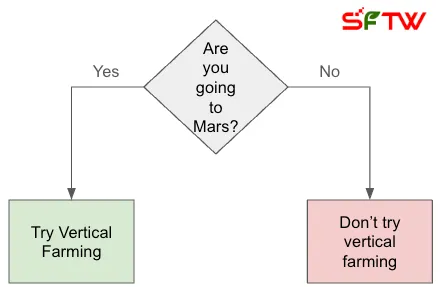

I had ended the piece with this graphic to call out the futility of vertical farming to provide everyday products like lettuce.

Venture capitalist Surendra Reddy of 451 Ventures, wrote a scathing LinkedIn article on vertical farming and twisted the knife, with his interesting title “DOTCOM vs DOTAG: The Rise and Fall of AgriTech’s Billion-Dollar Bubble.” Surendra is very much on point, when he comes at it from a funding and operational perspective, when he talks about vertical farming in general.

- Unrealistic Scaling and Over-Expansion

- High Capex and Operating Costs

- Overreliance on Venture Capital and Debt Financing

- Inefficient Capital Allocation

- Technological Viability and Overhyped Potential

- Lack of Ecosystem Integration

It is hard to argue with any of his points. I understand his viewpoint, given he is a VC.

Though I strongly believe as I argued in my January article, the problems are upstream compared to the funding model being used, the amount of capital raised, and the technology being used. The problems were and continue to be in the lack of first principles thinking, and understanding who the customer is, what is the problem being solved, and what are the expected outcomes.

Surendra’s conclusions in his article are much more on point and expansive, as they take into account other issues like industry collaboration, energy needs, and affordability.

- Collaborative ecosystems that maximize resource efficiency by integrating energy, technology, and food production, leading to lower operational costs.

- Circular systems that recycle energy (e.g., using waste heat from industrial processes for greenhouse heating) and reduce reliance on external energy sources.

- More affordable food production by leveraging economies of scale and shared infrastructure, which would likely have achieved broader food affordability and availability for the masses, compared to the high-cost model of individual vertical farms.

- Sustainability: By integrating renewable energy and resource recycling, food clusters can achieve better environmental outcomes and contribute to long-term food security.

AgFunder did an autopsy on Plenty and published an article last week, with some interesting comments in it.

“It was part of the game,” agrees Gordon-Smith. But, he adds, Plenty took it to new heights. “They were talking about growing watermelons and fruit trees indoors. I mean, yeah, technically you can, but economically? Not even close—definitely not at scale, and not anytime soon.

Other commentators complained about the “Silicon Valley” vibe of the company, which I don’t have a lot of patience for and AgFunder should not be publishing such stuff.

“Plenty always struck me as the most ‘Silicon Valley’ vertical farming company out there,” says Agritecture CEO and indoor agriculture expert Henry Gordon-Smith.

“You can see it in everything—from the headquarters location to the Bezos backing to the way the leadership talks. There was a lot of big, bold language about revolutionizing food.”

Such talk plays well with investors, he adds, but it’s useless currency in agriculture.

Having worked at startups at different sizes, and also at large companies like Amazon and Google, the fancy perks are mostly at Google, Facebook, and these trillion dollar companies.

Barista at Google? Check. Massages at Google? Check.

At our startup, we had a crappy coffee machine, and tables were butcher’s block wood tables for the team to sit around.

Also, such talk plays well with investors is an interesting comment.

If there are investors who are excited about the approach, they will be left with just holding a big strawberry in covering their private parts and no clothes.

Louis Vuitton or Walmart?

My issue is that Plenty is still not being intellectually honest about what they are trying to do.

A spokesperson for Plenty highlighted the company’s work in strawberries, which is ongoing: “After evaluating all of our strategic alternatives, we have determined that pursuing a restructuring process is in the best interests of Plenty and all of our stakeholders. Through this process, Plenty will be better positioned to continue working toward our mission to make fresh food accessible to everyone, starting with the year-round production of premium strawberries in our innovative vertical farm in Virginia.”

I am amazed Plenty is still giving us the drivel about their “mission to make fresh food accessible to everyone.”

We have seen it again and again in the data that the idea of using “vertical farming to make fresh food accessible to everyone” is flawed at many different levels. I agree with the mission statement, but do not agree with it for Plenty. If as a society, we want to make fresh food accessible to everyone, it is a great mission and goal to have, though vertical farming will be at the back of the line of potential solutions to solve this problem. Ideally, it should not even be in the line.

If Plenty had restated their mission as being able to provide premium products like strawberries with unique characteristics to a highly affluent segment of the population, it is much more believable and intellectually honest.

Adam Bergman is way more straight about Plenty’s prospects.

Bergman is optimistic about the company’s prospects with strawberry farming—at least as long as Plenty has the Driscoll’s partnership.

“Driscoll’s has a bunch of berries that are incredibly tasty, but they can’t grow them outdoors and get them to market with a long enough shelf-life to appeal to consumers,” he says.

“In the long-term, I am optimistic that with the support of Driscoll’s, the global berry leader, Plenty will be able to grow some of the best strawberries in the world at its Virginia facility.”

I question a business model which relies on the business of just one large customer, even though Driscoll’s is one of the most amazing, future looking and innovative companies out there.

The problem is not that the only large customer is Driscolls, but the problem is that you have only one large customer.

If you were working in defense, or space launches, then I can still understand how a business model with just one very large customer could be successful (for example, the US government).

I was on the receiving end of this problem, when I worked at Harvestmark (now called iFoodDS) and a plurality of our revenue came from one company which happened to be Driscolls. It made resource allocation and investment decisions, and strategic changes in the direction of the company extremely difficult, and none of it was Driscoll’s fault.

Plenty is going to focus on premium strawberries, and they should be intellectually honest about their approach, though having most of your revenue come from just one customer is going to be a significant challenge for them.

Louis Vuitton

On the other hand, vertical farming company Oishii continues to focus on premium strawberries. Premium strawberries from companies like Elly Amai can sell for $ 20 a berry!

Oishii, a company that grows Japanese strawberries in the US, made headlines six years ago for selling a $50 box of strawberries that became trendy with American chefs, who liked to use them as the perfect minimalist end to an ornate omakase meal.

The high-end fruit company Elly Amai said in a statement that its $20 berries “require a lot of skill and special techniques to grow” and, unlike berries in the US, “are meticulously monitored for quality and taste”.

Oishii’s branding and positioning is high end, drips exclusivity, elegance, and is steeped in Japanese tradition.

The Omakase Berry has a delicate sweetness, aromatics that fill the room, and a deliciously creamy texture.

A unique strawberry, unlike any berry you’ve tasted, the Omakase Berry is a truly one-of-a-kind eating experience.

The Omakase Berry gets its name from the Japanese phrase "we leave it up to you," where a chef is entrusted with giving the best experience possible to the diner. We’ll leave it up to you to enjoy the Omakase Berry however you see fit.

For Oishii to increase its margins, it can try to raise pricing, and try to be more efficient in their operations to reduce costs.

Strawberry harvesting by humans is the most expensive operation in strawberry production. Oishii already uses significant robotics in their production through their partnership with Yaskawa Robotics.

Oishii has acquired robotics company Tortuga AgTech, which has built and deployed many strawberry harvesting robots and has raised about $ 55 million in venture capital since 2016.

Tortuga AgTech was having financial difficulties as they struggled to raise their next round of funding and keep it as a going venture. Some of their funders pulled out at the last minute.

The acquisition by Oishii at least lands the team a chance for the technology to be used and adapted by a strawberry production company. I do not have any inside information, but my guess is that Oishii got a good deal due to the distressed state of Tortuga AgTech.

Oishii will acquire Tortuga AgTech’s highly effective advanced robotics technologies, including AI-driven models, frontier robotics software, and custom hardware. Oishii will integrate these technologies with their proprietary robotic systems and ongoing strategic partnership with Yaskawa Robotics—one of the world’s leading robotics companies.

Tortuga AgTech’s top machine vision, AI, software, and hardware engineers will join forces with Oishii’s industry leading engineering team to spearhead cutting-edge advancements in robotic harvesting technology. This combination of tech and talent has the potential to make the company’s harvesting capability truly and fully autonomous.

The acquisition of robotics capabilities for harvesting along with their existing Yaskawa Robotics capabilities will help Oishii to continue to be more efficient on the operational side for their premium strawberries and expand their margins or reduce their unit losses.

More acquisitions to come

The situation of Tortuga AgTech is not unique when it comes to robotics companies. Last week Farmwise announced their ceasing of operations by April 1st, 2025. They are looking for potential buyers of their technology, very similar to what Tortuga AgTech did.

This is not a new phenomenon. It is especially true when many players rush in to fill an economic need based on new technology or some other change. In spite of many players going out of business, or getting acquired, overall it is great for the industry, as it creates excitement, new innovations, new experiments with business models, and moves us forward.

For example, in the early 20th century, hundreds of companies were founded to build gas-powered tractors and sell them to farmers, but by 1929 (this is an excerpt from the book “Tractor Wars - John Deere, Henry For, International Harvester, and the Birth of Modern Agriculture” by Neil Dahlstrom.

Only thirty-three American farm tractor manufacturers remained in 1929, and mergers, consolidations, and bankruptcies continued to narrow the field. In its overview of the tractor industry in early 1928, the Tractor Field Book surmised that "large numbers of inefficient machines were discarded during the five-year period, 1920 to 1924" as many were built by "companies whose efforts were largely experimental."

The 2024 Mixing Bowl landscape on Crop Robotics showed more than 350 companies. I expect that number to go down in the next 5 years.