Lindy effect in agriculture

Welcome to another Sunday edition of SFTW!

This week's edition talks about the relative lack of churn in the rank of incumbents within agriculture.

Happenings

- Upcoming AgTech Alchemy events. Seattle (May 19, 2025), Fargo (June 12, 2025), Silicon Valley (June 12, 2025)

- Second part of the GenAI in Ag whitepaper to be released on May 20, 2025. You can get the first part here. It is free for SFTW members.

Build Less, Scale Faster: The Rise of White-Label Platforms

Ag leaders aren’t asking “Can we build it?”—they’re asking “Should we?” White-labeled platforms are helping agribusinesses move faster and deliver on strategy while staying focused. From carbon tracking to digital agronomy, e-commerce, and lab insights, leaders are choosing to scale through their brand, not by building new tech stacks.

Customers don’t care who built it—they care that it works. With white-labeled tech, you can go to market fast with your logo, your workflows, and our managed infrastructure behind the scenes.

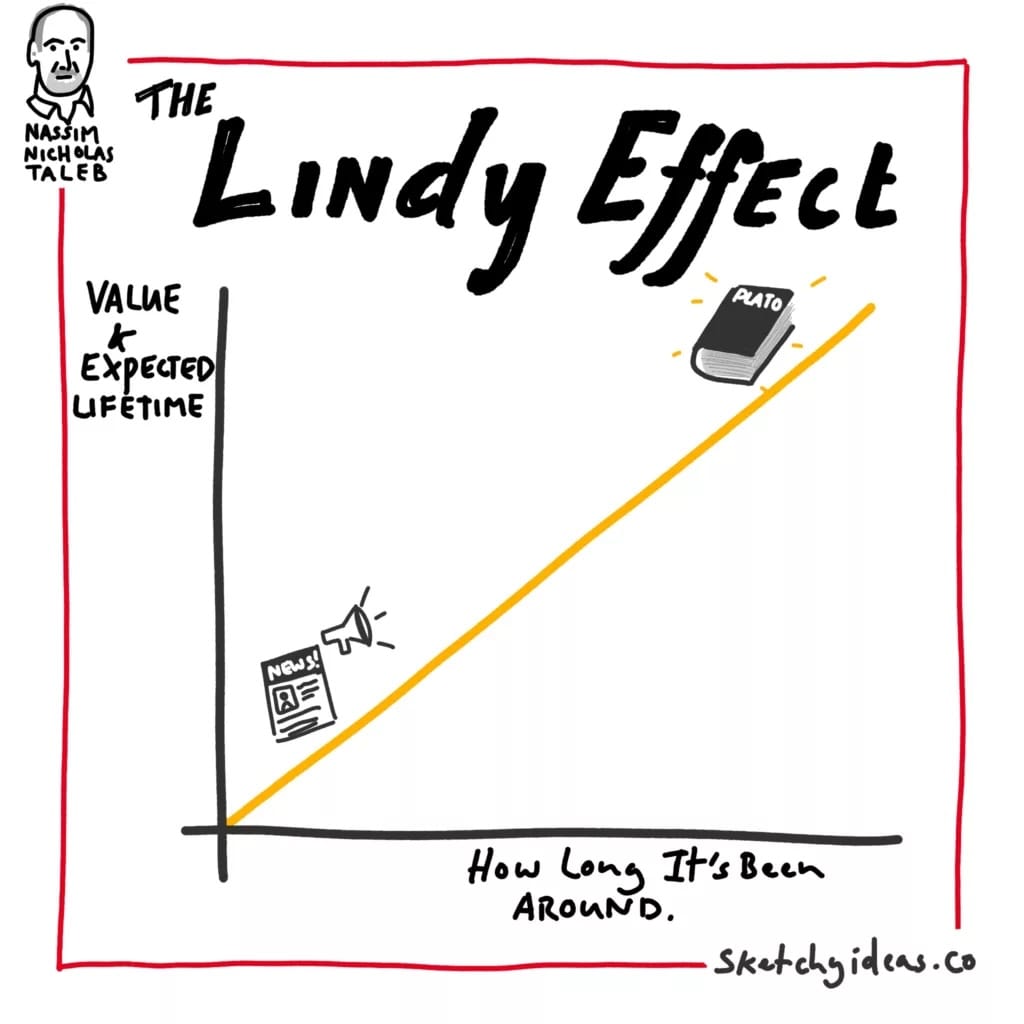

Lindy effect: If a book has been in print for 40 years, it is likely to stay in print for another 40. If it’s new, it might vanish next year.

The concept originated from conversations among comedians at Lindy's Deli in New York, who observed that the longer a show had been on air, the longer it was likely to continue.

It was formalized and popularized by Benoit Mandelbrot and later expanded by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (a mathematician and an obnoxious blowhard) in his book Antifragile.

We can say with a high degree of confidence that Shakespeare will still be popular a few hundred years from now, and Plato will be influential a few thousand years from now.

Image source: Sketchy Ideas

The Lindy effect is typically seen in non-perishable items like ideas (e.g. religion), practices (e.g. contracts), basic tools (e.g. hammers) etc. Some other non-perishable items like business models like subscriptions have shown strong Lindy influence.

Companies are less likely to show the Lindy effect, though a brand like Coca-Cola has stayed strong for many years. (It is not guaranteed it will, though it is in a fairly strong spot).

The list of most valuable companies in the US changes quite a bit every few years.

Within agriculture, one could say companies are showing a form of Lindy effect, especially the incumbents.

For example, within the seed and chem space, four companies control the majority of the share of wallet from growers. More importantly, even though these companies have gone through many different transformations, they have often thrived and survived through multiple geopolitical events, pandemics, trade wars, technology shifts.

Syngenta traces its history back to 1758 through the founding of Geigy, a Swiss chemical company. Over the next two and half centuries, through multiple acquisitions, mergers, divestments, Syngenta in its current form emerged in the early 2000s.

Bayer was founded in the late 19th century in Germany and continues to evolve through their acquisition of Monsanto as late as 2018, though the Crop Science division is in an existential crisis right now. Corteva traces its origins back to the late 19th and early 20th century through their Dow & Dupont links. BASF similar has been around since 1865.

The headquarters of "Fried. Bayer et comp." in Heckinghauser Strasse in Barmen-Rittershausen (1863) (Image Source)

The story is similar on the equipment side. Deere has been around since 1837. Though CNH in its current form was formed in the late 20th century, its acquisitions and divestiture trace its history back in the 19th and 20th century through FIAT and brands like Massey Ferguson. Kubota was founded in the mid-19th century whereas Mahindra has been around since the middle of the 20th century.

The data with off-takers is similar. The ABCDs of the world control a plurality of products moving through the supply chain. ADM (1902), Bunge (1818), Cargill (1865), and Dreyfus (1851) have been around for a long time.

So why have these companies survived and thrived for so long?

There are different reasons for different sectors within ag, and slightly different reasons for different companies, but they can be broken down into four main categories.

- Distribution

- Physical infrastructure

- Fragmented markets

- Tech innovation and scaling

These factors are not independent of each other, but they build on top of each other to increase the entrenchment of these incumbents. If your company is taking advantage of all four factors, the Lindy effect will be strong.

Let us look at some examples across offtake, OEM, and seed & chemical companies in agriculture.

Offtakers

Offtake requires a large and connected physical infrastructure with grain elevators, storage facilities etc. The storage infrastructure has to be connected with a logistics infrastructure over rail, water, and land with access to terminals and ports to connect supply with demand.

If you look at the history of the ABCDs over the last 150 years, Cargill was building and acquiring grain elevators in the mid-west right from the beginning of its history and connecting it to the expanding rail and barge network.

As early as 1885, Cargill already had access to 102 grain elevators in the midwest with connections to rail lines. Over the years, Cargill has continued to expand their physical infrastructure and distribution network into multiple product types like animal feed, protein, grain, cocoa, and almost any grown, transacted, and transported commodity in the world.

(To know more about Cargill’s history, do check out the massive 900 page book “Cargill: Trading the World’s Grain” by Wayne G Broehl, Jr.)

Given the fragmented nature of many of these supply chains, the offtakers have been able to acquire companies constantly to expand their operations and reach.

It is extremely difficult and very expensive for a new company to build out this physical infrastructure and get access to the distribution network. These companies have deep pockets, strong political connections, and given their bets spread across multiple supply chains, they can handle a downturn or any adverse conditions in a much more resilient fashion.

These companies continue to innovate (albeit much more slowly compared to other areas) and add new capabilities to their product portfolio.

Seed & chemical companies

Seed & chemical companies have followed a similar path, but their access to distribution has been around the distribution of their seed and chemical products to farmers, retailers, cooperatives etc.

Seed & chemical companies have built a large production and distribution network with access to manufacturing facilities in different regions of the world, including seed manufacturing.

Similar to the off takers, they have followed a frantic pace of mergers and acquisitions to solidify their position along a wide variety of products and regions. The chart below is from 2019, but illustrates the phenomenon very well.

Image source: “The Sobering Details Behind the Latest Seed Monopoly Chart” (Civil Eats, January 11, 2019)

Seed & chemical companies have leaned more heavily on technology innovation and scaling through products like GM seeds . Over the last 30 years, GM seeds and Roundup Ready Crops have been one of the best tech and business innovations from a business standpoint. These companies have been able to bundle seed & crop protection products together and created a compelling offering for their customers. They have been able to use a better technology bundle (for yield) to then lean into their distribution network to help them scale very quickly.

Bringing a new GM seed or a new chemical molecule to market is a very expensive and time consuming position. These incumbents have the means, the expertise, and the process knowledge to continue to maintain a leadership position in the space for some time to come, though they might have some potential chinks in their armor. (We will investigate them in the last section)

OEMs

OEMs like Deere have followed a path of constant technology evolution, and then leaning onto their distribution network to scale their innovation. Companies like CNH, and AGCO have managed to maintain their position to a large extent through the access to their distribution network and acquisitions, though compared to Deere they have struggled on the innovation side.

Companies like Mahindra and Kubota have leaned heavily on their service and parts network to provide a good customer experience to maintain their Lindy effect.

There are many startups in the graveyard of equipment startups, especially in the robotics space lately. In most cases, even if you have a good product, if you cannot find distribution and service capabilities, you are NGMI.

Can the “Lindy effect” be broken?

(Full disclosure: I DO NOT have any financial interest in any of the companies mentioned in today's article, nor do I have access to any insider information.)

If you are a startup in the OEM, seed or crop protection space, one of the better courses of action for you is to find strategic partners, and set yourself up to be acquired, as you will struggle to find distribution.

As my friend Dan Schultz says, if you want to follow a different path, you will have to create your own category. You will have to think orthogonal to how the incumbents are thinking

Offtakers

Among the three sectors mentioned above, the offtakers might have the best chance of extending their “Lindy effect” in the future. The physical infrastructure is absolutely needed to store and move products through the supply chain.

The distribution and physical infrastructure of these offtakers is extensive and addresses the needs of a variety of supply chains (grain, animal feed, other crops, protein etc.) It will be extremely difficult for a new player (or an existing non-ABCD) to come in and build new infrastructure, which is economically efficient.

Cargill’s Ocean Transportation flows

Seed & chemical companies

Technologies like gene editing, or CRISPR are potential threats to these companies, if brought to market by startups or other smaller companies.

FBN is an example which comes closest to trying to disrupt the traditional seed industry, but it has not made a huge dent into their business.

The “Lindy effect” is strong for seed & chem companies, but not as strong as offtakers, as there are some possibilities where either due to regulation (certain or all chemicals get banned), a more nimble and less expensive technology could trap one of these incumbents in an innovator’s dilemma, if they didn’t pay attention to some of the latest developments in the space.

Distributed breeding techniques can be orthogonal to the incumbent breeding programs which rely on very expensive R&D projects for a general purpose product.

A new technology like laser, hot oil, or light based crop protection products, (for example, Carbon Robotics, Laudano and Associates, Tric Robotics etc.) could put these companies at a disadvantage to a startup working in the space, as it would not require the use of agrochemicals. If these startups are able to set up their own distribution network, then they have a chance to create their own category.

It could shift the value pools from seed and chemical companies to equipment companies.

On the fertilizer side, a more distributed production process like green ammonia, does not rely on the massive scale requirements of the Haber-Bosch process. A distributed manufacturing process does not play to incumbent strengths of massive production processes. The decentralized model can provide more price stability, with usage being very closed to production.

Seeding a New Pathway: The Opportunity for Distributed Green Ammonia

OEMs

OEMs with their strong brand position, a large distribution network of owned and independent dealers, have a strong Lindy effect.

What are some of the potential threats to the OEM Lindy effect?

The top 4-5 OEMs have continued to push for larger and faster equipment within the commodity row crop space in the Americas, and to some extent in Europe. This has been driven by farm consolidation and the need to have a human driver in the equipment.

If autonomy becomes feasible and widely available, it could allow for a small form factor for the equipment, which is controlled through software and an operations center. Even in this case, access to a strong distribution and support network will be crucial to have any chance of higher levels of adoption.

We have examples of companies like SwarmFarm Robotics, Solinftec, and Sabanto trying to do the same with a smaller and cheaper form factor enabled by software and network operations centers. The smaller form factor could allow for a more nimble and less asset heavy distribution and support infrastructure.

We do have the example of Tesla which came in with a different product, and built out its distribution and service network in the automotive space. It is not uncommon for Tesla to dispatch their mobile technical unit to your house to come in and diagnose any problems and maybe even fix them. Building this distribution and service network is expensive, but is not impossible.

AGCO (an incumbent) has built a mobile and more responsive support center through their app FarmerCore service, to augment their existing dealer sales and service network.

The Lindy effect will continue to be strong in industries with large established physical infrastructure, and access to distribution. Oil companies like Chevron, which started in 1879 (as Pacific Coast Oil Company) have built a vertically integrated oil and gas physical infrastructure over more than 100 years.

Within agriculture, off-takers will probably have the strongest Lindy effect, though entities like grocery retail and associated services will have lower Lindy effects. They are more prone to technology and business model disruption, due to their regional relationship based focus. For many of the small and medium retailers, their distribution and support networks are localized, they do not have a strong advantage when it comes to technology adoption, and have limited R&D dollars to create new products.

Lindy effects can be weakened and ultimately broken only through thinking differently than the incumbents. It is possible by playing a different and orthogonal game than incumbents, and starting in an area which will either be ignored or create innovators' dilemma for incumbents.

Are there other possibilities on the horizon right now, which could break the Lindy effect for incumbents? I would love to hear from you.