"Looking back with concern and humility"

SFTW Convo with Shubhang Shankar of Syngenta Ventures

SFTW Plus is the paid version of “Software is Feeding the World.” SFTW Plus includes all Sunday newsletters, SFTW Convos series, Scaling Innovation series, and access to the archives. AgriFoodTech leaders subscribe to SFTW Plus to get insights through frameworks on how technology can have a positive impact on their business.

Shubhang Shankar is one of the foremost thinkers within the Agrifood community. He is the Managing Director at Syngenta Group Ventures, the venture capital arm of Syngenta Group. Shubhang and the team at Syngenta Group Ventures has invested in companies like Decibel Bio, Agrolend, Green Eye Technology, Vestaron, Sound Agriculture among others.

Shubhang has a unique and oftentimes contrarian way of looking at things. He is extremely well-read, pulls examples and analogs from multiple sources to inform his work at Syngenta Group Ventures.

He is not afraid to express his contrarian views in his own inimitable style. Shubhang and I both went to the same undergraduate college system in India (different campus). Due to this, I believe I have some sense of understanding his thought process, and where he is coming from.

My only complaint about Shubhang is he needs to publish more of his thoughts and let them out in the world. In lieu of that, given the interesting times we live in, the next best thing I could do is to get him to talk with me for an hour and a chance to pick his brain and understand how he thinks, how he makes decisions, and where he thinks the world is going..

I hope you guys enjoy reading this conversation, as much as I enjoyed having it.

Summary of the conversation

Shubhang reflects on his previous articles and clarifies that his "anger" was more concerned about AgTech's direction. He discusses the boom-and-bust cycle in the sector, the suitability of VC funding for different types of agricultural innovations, and the importance of corporate venture capital.

He believes venture capital is crucial for starting projects but not always for seeing them through. He also touches on regional differences in entrepreneurship, particularly the U.S. as the "spiritual home" of VC, and the potential for disruption from India. Shankar advises young people entering the workforce to explore different experiences and not to feel pressured to choose a fixed career path early on.

Shubhang Shankar, image provided by Shubhang Shankar, artwork by EI

“Looking back in anger or disruption”

Rhishi Pethe: It’s 2025. About five years ago, you wrote an article (“Look Back in Anger Or Disruption that Incumbents can love – AgTech in the 2010s”) which totally blew up, for all the right reasons. You made some predictions about the future, and like always, some of them didn’t pan out. In 2024, you followed it up with a super honest look back (“Look back in (even more) Anger – a ‘Ruckblick’ four years on”), what you got right, what you didn’t. Some stuff, like the VC funding, you actually called pretty well, even if it showed up a few years late. In both articles, you said you were angry, and in 2024, even angrier. So let’s start there. How are you feeling about the industry now?

Shubhang Shankar: Firstly, rhetorical titles are tricky, you don’t know how people will interpret them. Anger isn’t really an emotion I associate closely with myself. It wasn’t about being angry. When I wrote that first article in 2020, I approached it with humility.

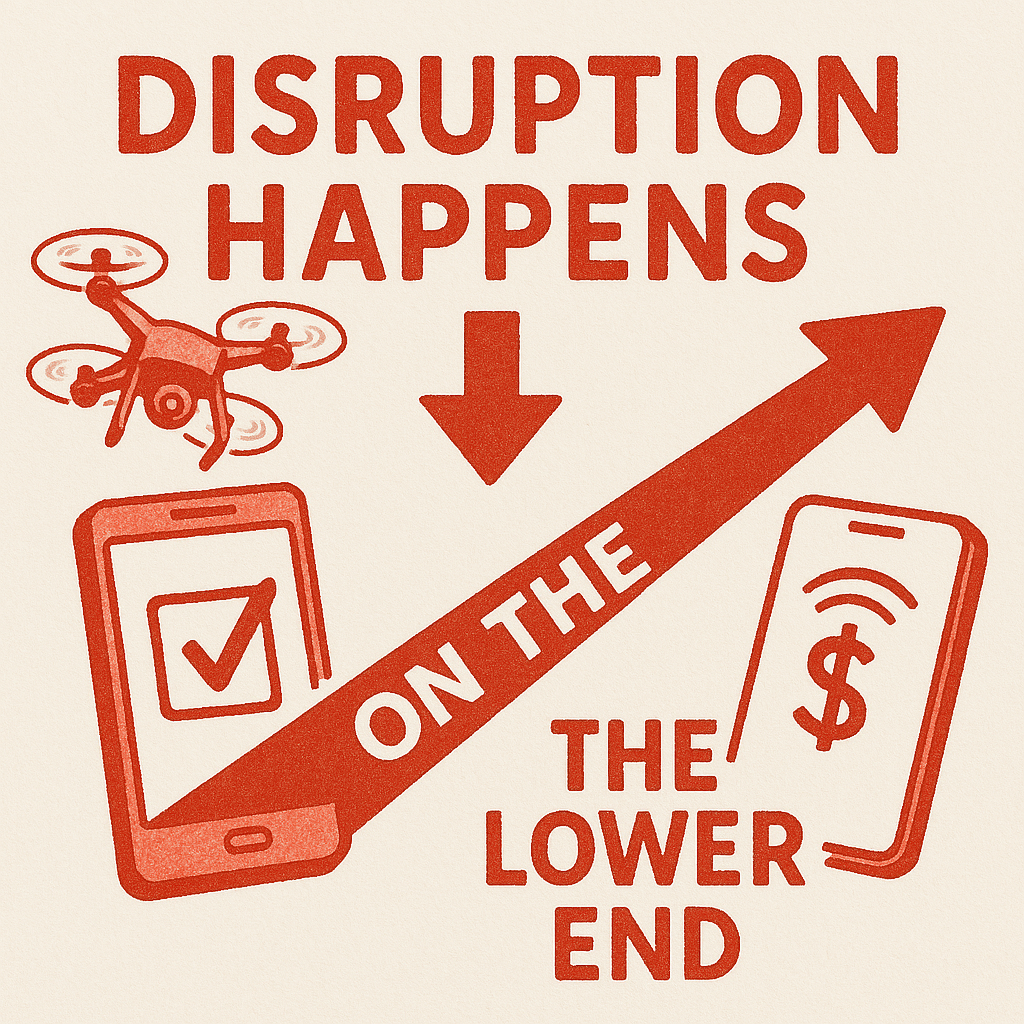

At its core, the intent of the article was to ask whether we’re getting stuck in a cycle of incremental innovations that aren’t bold enough, that don’t stray far enough from the straight and narrow. Or are we actually being truly disruptive? That’s what much of the article explored, can we really call what we’re doing true disruption? And then there were other parts that looked at why real disruption tends to happen the way it does.

So I approached it from the standpoint of: we have a great opportunity in front of us, could we be doing more? I wouldn’t even go so far as to say I stated definitively that we should be doing more. It was more of a question: could we be doing more? Are we focusing on the right problems, for the right people?

The concern I did express, and it wasn’t anger, came from some research I had done on clean tech. In the early 2000s, clean tech looked like a hugely promising and absolutely necessary space. But it went through a wave of failures that set the sector back and turned investors off for quite some time.

And I worried that AgTech could go the same way, not because of bad intent, but because we might focus on the wrong things, or fail to ask whether the asset class aligns with what investors expect.

And in doing so, we might disappoint investors, let customers down, and end up dimming the promise of AgTech for a while. A kind of "once burned, twice shy" effect.

The retrospective, which came four years later, circled back to those points. In 2020, I had thought it was a good moment to take stock. But the following two years, 2020 to 2022, only intensified the conditions I was concerned about.

I think it’s widely acknowledged now that those years were marked by irrational exuberance across many asset classes, including ours. And the correction that followed, that decline, was real. It affected investors, it affected companies, and it affected individuals. And I think the pain of that correction was probably deeper because of the buildup that came before.

So the second article didn’t come from a place of anger either. It came from a sense of asking: were we, as a sector, willfully blind to some of the warning signs? Did we get swept up in the hype? And honestly, that happens really easily, we’re all human.

So no, I wouldn’t say there was anger. What I felt was a need to be honest with ourselves. If we look at how much value we’ve actually delivered, to customers, to the industry, it’s clear we still have a long way to go.

If I had to sum it up, I’d say that in 2021 and 2022, maybe, like Bush in Iraq, we put up the “mission accomplished” banner too early. We mistook the influx of capital as a sign of success, when clearly, it wasn’t. Just like the lord, the market giveth, and the market taketh away, and when it taketh away, it really hurts.

That’s where I think we are as a sector right now. And the questions I raised back in 2020, unfortunately, it gives me no joy to say this, are now becoming mainstream. People are finally asking whether a given challenge is actually suitable for venture capital. And from my perspective, the answer is yes, for certain types of problems.

What I think the last few years have shown us is that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution for agriculture. You can’t apply pure venture capital to every fundamental issue in this space and expect it to work. That’s how I’d describe the arc between those two articles.

I work in corporate venture capital in agriculture, and I’m excited to show up and do this work every day. I still believe deeply in the long-term potential of this space. But I also think we went through a classic boom-and-bust cycle, and it left scars.

Venture Capital Model for AgTech

Rhishi Pethe: You’ve raised two big questions. First, is venture capital the right kind of funding for the types of problems we’re trying to solve? And second, are we even solving the right problems? Are we thinking big enough?

It’s easy for people to just say, “VC isn’t the right fit,” and leave it at that. But like you said, there’s a lot of nuance here. So let’s dig in a bit more. What kinds of problems in agriculture actually do make sense for VC funding? And how does that overlap, or not, with what a corporate venture group like yours looks for?

Shubhang Shankar: If I can reference your own article about vertical farming and Mars, I think that’s a great example of a subsegment in agriculture that probably wasn’t well-suited for venture capital. And today, we’re seeing signs of that, there are issues not just at Plenty, but also at Ÿnsect, Infarm, Bowery, and others.

It’s fair to say that some of these highly capital-intensive, early-stage, speculative technologies, where we knew the path to commercialization would be long, were clearly not a good fit for the venture capital model. In hindsight, those were actually the easier calls to make: venture capital just doesn’t align well with that kind of horizon.

I think even the investors and entrepreneurs in this space would probably agree with that. What we’ve seen happen with some of these companies is really just a case of investors losing patience, because they have a finite investment horizon.

If you look at the vertical farming space, for instance, most of those companies were making steady progress in terms of technology. But if they were going to succeed, it would’ve taken far longer than what venture capital investors were willing to wait for.

So in my view, the core problem in that sector was a mismatch between the timeline needed to develop the technology and the timeline venture capital typically works on. I’ve attended a few events by the Good Food Institute in Israel, and they’ve made a similar point.

For things like cellular meat or precision fermentation, they argue that most of the funding needs to come from government or public sources, because the time horizons are just so different.

There are many such examples, segments where venture capital isn’t a good fit, and people are realizing that over time. And it really comes down to the timeline. That said, I’m a big believer in venture capital. We absolutely need high-risk capital to get speculative businesses off the ground. We need an asset class that’s comfortable with a high failure rate. Without that, the world would be a poorer place. And I think agriculture needs it too.

The real question is: what kind of innovation can venture capital support?

I still believe in the potential of robotics. It’s inevitable. We don’t know what the exact timeline will look like, just like Tesla didn’t become a trillion-dollar company overnight. It went through a long, slow period of growth before it took off. I see agricultural robotics, whether it’s for precision spraying, harvesting, or weeding, on a similar path. Venture capital is well-positioned to support it, at least in the early stages.

And that’s the key point: venture capital needs to start the job. It does not need to finish it. I think that’s a really important distinction. VCs can take these innovations to the point where they either become self-sustaining or where another, more patient asset class can step in and take over.

That hybrid model, where VC kickstarts the work and other forms of capital step in later, makes a lot of sense, especially in areas like robotics or broader mechanization, where you’ve got that hardware-software combination.

I also still believe in sectors like e-commerce and fintech, which VC has traditionally supported. Those models have a place in agriculture too. Sure, there are specific challenges when it comes to financing and distribution in ag, but those can be solved.

When we talk about long-gestation businesses, like trait discovery, gene editing, or biologicals, the challenge becomes more structural. Venture capital can help turbocharge one part of the commercialization journey, but the rest still relies on traditional models. These tend to be capital-intensive businesses.

Unless there’s an exit at the right point, typically through acquisition by a larger company, they won’t fit the pure VC model. And that brings us back to the same point: VC gets it started, and more patient capital carries it forward.

So, without going into too much detail on specific segments, I’d say venture capital plays a critical role in AgTech, especially in getting things off the ground. We need to get more things started. Some will succeed, and some will move into other funding models.

What went wrong during the bubble was that too many speculative ventures got backed by too much capital, too quickly. And the risk got mispriced. That’s what happens in any bubble. Now, we’re just seeing the correction, a repricing of that risk.

And yes, I think it’s worth underlining what you said: venture capital can start the job, it doesn’t have to finish it.

Rhishi Pethe: I think the nuance gets lost because most people talk in a binary way. Outside of a few big examples, like SpaceX getting VC funding, or supersonic company Boom. I don’t know their exact timeline, but I doubt that supersonic flight is happening in three to five years. It’s probably a much longer play. Still, they’ve raised venture capital.

So maybe that’s what we’re going to see more of, VCs stepping in to get things started, and then more patient capital stepping in later to carry it through.

You mentioned chemical discovery too, and how that has to go through regulatory hurdles. If I remember right, before Monsanto acquired Climate Corp, a lot of the early AgTech didn’t focus on software or hardware, it was mostly biotech. And that did get VC funding. So maybe that’s the model. VCs fund the early stage, and then eventually there’s an acquisition by a major which helps scale it.

Shubhang Shankar: Which, by the way, is exactly how the pharma business model works, and it seems to work brilliantly there. I think over time, something similar could evolve in our space too, once we work through a few more of the nuances.

Before Climate Corp came along, most venture capital in agriculture functioned as off-balance-sheet R&D. I wouldn't say it was exactly like what big pharma was doing with third parties, but the overlap was pretty strong. And that’s perfectly fine. That model can work, it just comes with its own complexities.

Take the well-known stat in pharma: it costs around $300 million to bring a single molecule to market. What we haven’t cracked yet is a model that brings that number down significantly, not from $300 million to $30 million, even just from $300 to $250 million. But $250 million is still a massive amount for venture capital to absorb.

So the real question in biotechnology becomes: what’s the right model? And I think the answer is that venture capital should kick things off, get the science or the tech to a certain point, and then more patient capital, whether through a corporate acquisition or some other asset class, steps in to carry it forward.

You could look at it another way. What’s the typical endgame for a biotech startup? In most cases, it's to be acquired, and that’s no different from what we see in pharma. Most successful pharma startups eventually get bought out.

On the other hand, with robotics or digitally driven ag companies, there's actually a real possibility that they could go on to become viable, standalone businesses. And that’s what I’m really waiting to see, a new, successful, independent company in agriculture that’s built from the ground up and makes it all the way on its own.

Rhishi Pethe: We’ve seen that kind of model play out in pharma too, take Genentech, for example. They weren’t one of the big players when they started, but now they’re a major incumbent. Same with Moderna.

You mentioned patient capital, either coming from off-balance-sheet sources or through a corporate VC fund, What was the original thinking behind setting up these corporate VC funds?

Syngenta’s been in the game for a while, sure, but compared to other industries, it feels like most corporate VC arms in ag only really started showing up in the last 20 years?

Shubhang Shankar: In our industry set up in the last five years honestly.

Corporate Venture Capital within and outside AgTech

Rhishi Pethe: John Deere has been around for 150 years. BASF has been around for 100 years. Syngenta under various names has been around for a long time. What was driving a need to have a corporate VC fund in the last 10 years?

Shubhang Shankar: Let me just start with a quick disclaimer, I wasn’t around when Syngenta Ventures was set up. That was done by people far smarter than me. So I can only guess what their original motivations might have been.

But I think, at its core, the decision came from a place of humility. There was a recognition that the kinds of innovations needed to solve the challenges of the global food system over the next 20, 30, 50 years would be multidisciplinary. And they’d go well beyond the traditional capabilities that any incumbent company, ours included, typically has in-house.

If we take Syngenta as a proxy for agri-input companies, our core strengths lie in chemistry and biology research. Our business is built on converting intellectual capital in those areas into physical products, and that model worked really well for decades.

You mentioned John Deere earlier, but I’d say our broader industry really took off after the Second World War. The goal was to improve physical implements and make agriculture more input-intensive and higher yielding. And I think we did a great job delivering on that.

Now, the question has shifted. If we’ve hit certain biological or physical limits on how much more we can squeeze out of inputs and yields, then where do we look for the next layer of efficiency? That’s where we saw the need to expand our research approach, from synthetic chemistry to biologicals, and from pure lab work to integrating digital technologies. Over the past 20 years, digital innovation became a major driver, and we had to start incorporating that too.

The thinking was this: tomorrow’s innovation will require us to synthesize multiple technologies, many of which we don’t have in-house capabilities for. And naturally, high-risk, early-stage research is better done in startups, startups that have the flexibility to fail, the freedom to explore.

So the industry as a whole benefits when there’s a vibrant ecosystem of early-stage companies tackling speculative problems. Even if they fail, they move the field forward.

In that sense, I believe the decision to create Syngenta Ventures, and I imagine it was similar for other corporate VC arms, was based on both push and pull factors. We didn’t want to miss out on innovation happening outside our walls, and we saw the opportunity to tap into it in a way that supported the whole industry.

That motivation seems pretty consistent across industries.

I’ve spoken with corporate VC teams from major automotive companies in Germany and the U.S., and they echo the same logic. In the auto industry, for example, it’s becoming harder to differentiate purely on internal combustion technology.

I remember someone from BMW Ventures saying that BMW now operates more like a coordinator of different tech vendors, bringing together components and systems.

Sure, there’s still innovation in the engine itself, but a lot of the value today comes from integrating digital tools and vision systems, putting an iPad into an electric vehicle, and suddenly it’s a Tesla.

So the automotive world also shows why corporate VC becomes essential. And for us, that was a big part of it.

From around 2014 to maybe 2017 or 2018, there were only a handful of corporate VC units in our space. More players started showing up after 2019 and especially after 2020. So in the broader scheme of things, corporate VC in agriculture is still a relatively recent development.

But it’s a healthy mix now. You’ve got veteran funds like ours, Syngenta Ventures is in its 16th year, and you’ve got newer funds that are just three or four years in. And I say the more, the merrier. Because if we want to keep creating value, we have to become truly multidisciplinary.

Rhishi Pethe: You mentioned talking with BMW and the automotive space, are there lessons you’ve picked up from that industry that you’ve brought into your work? What kind of thinking translates well into this space? And on the flip side, what doesn’t really apply?

Shubhang Shankar: There’s always something to learn from other corporate VC units. And many of them raise the same core challenges. For example, it’s tough for a large corporation, one that’s designed to be cautious, and I mean that in the most positive sense, to suddenly adopt a startup-like mentality.

One idea that stood out to me in a discussion at one of these forums was the value of complementarity. When a corporate and a startup partner, both sides inevitably reach a point where they wish the other were more like them. The corporate wants the startup to be more structured, more process-driven. Meanwhile, the startup wishes the corporate were faster, more agile.

That mindset, where each side wants the other to change, is something best avoided. The most successful partnerships happen when both sides embrace who they are. The corporate lets the startup be a startup. And the startup recognizes the corporate for what it is. That’s when both parties can really bring their complementary strengths to the table.

Corporates bring scale, process, and deep market knowledge, and that’s exactly what they should bring. Startups bring agility and creativity, and they should double down on that. Collaborations usually fall apart when a corporate tries to turn the startup into a mini-corporate, or when a startup expects the corporate to behave like a startup.

That, I think, was one of the most important learnings, not just from an investment standpoint, but from a broader perspective on how corporates should engage with startups.

Rhishi Pethe: When you think about roles in corporate VC, what are some of the key skill sets you need to be successful, especially compared to being in a traditional VC role? Obviously, exits are one clear way to measure success. Are you actually picking winners? But beyond that, how else do you measure impact in a corporate VC setting? What does success really look like in your world?

Shubhang Shankar: I wish I had a clear answer, to be honest. When it comes to the skill sets needed, it’s a bit ironic coming from someone who wrote two articles with “anger” in the title, but I think optimism bias is essential, whether you’re a VC or a corporate VC.

Like entrepreneurs, you have to ask yourself, “what if this works?” rather than starting with all the reasons it won’t. That mindset isn’t always easy to maintain over time, but it’s critical. A good venture capitalist needs to believe in possibilities, and also be very aware of how much they don’t know, the “unknown unknowns.”

If you approach venture investing with a rigid scouting mentality, saying upfront, “this is exactly what I’m looking for”, you risk missing the richness and unpredictability the entrepreneurial world offers. And that, to me, defeats the very purpose of venture capital.

VC should be about going out into the world and letting it surprise you, letting it enchant you with ideas you didn’t even know existed. That sense of wonder is something a corporate VC really needs to hold on to.

At the same time, you also need discipline. You have to be skeptical enough to dig into claims, to investigate what you're hearing. You can't go in blind. It goes back to that Russian phrase: trust, but verify. That’s especially important when we look at some of the companies making headlines for the wrong reasons.

As a VC, corporate or otherwise, you’re a custodian of capital. In the case of corporate VCs, that means a large company has trusted you with its money. For traditional VCs, it’s the LPs. Either way, you have a responsibility to protect that capital. So you need both: optimism and discipline.

There’s one more thing I’d add when it comes to corporate venture capital. There are different schools of thought, but I think Nokia says it well: they describe themselves as a financial-first investor, but not a financials-only investor. That distinction really matters.

If a corporate VC unit is just chasing financial returns, then it might as well act like a passive investor. But that’s not the point of corporate VC. It should be about more than just returns, it should also spark innovation, create opportunities for learning, and open the door to meaningful collaborations within the organization.

That said, those strategic outcomes shouldn’t come at the expense of financial returns either. A peer of mine put it nicely, “The best strategic investments are also the best financial investments.” Whether you fully believe that or not, I choose to. Because I think corporate VCs have a duty of care to their organizations. We should actively seek out investments that make strong financial sense.

If you can square that circle, and it’s not easy, either personally or organizationally, I think that’s what it takes to be a strong corporate VC. Beyond that, there are just so many unknowns in this role. You’ve got to stay open and keep learning as you go.

Regional differences in entrepreneurship and venture capital

Rhishi Pethe: You grew up in India, and you live in Europe. You invest in companies all over the world. Do you notice differences in the types of entrepreneurs coming from different regions?

You mentioned the optimism bias, and I’m guessing that’s pretty universal among entrepreneurs, no matter where someone’s from. Are there other differences you see when companies approach you from different places? Do you have a mental model where you go, “Okay, this is coming from this particular context, so I need to think about it a little differently”?

Shubhang Shankar: Let me answer this in a way that might spark a little controversy. I see venture capital and entrepreneurship as deeply tied to America. For me, in many ways, venture capital feels synonymous with the U.S., and I don’t mean that as any disrespect to entrepreneurs in other parts of the world.

But venture capital, startups, risk-taking, personal freedom, a limited role of the state, all of that feels like it comes together most naturally in the U.S. I think America has found perhaps the optimal combination of those ingredients. To me, venture capital is as American as the bald eagle and the stars and stripes.

I see the U.S. as the spiritual home of venture capital and entrepreneurship. And honestly, every other ecosystem around the world seems to be trying to emulate that model. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then the U.S. has every reason to feel flattered.

The institutional support in the U.S., whether it’s legal, regulatory, or financial, is just on another level. It’s hard to replicate. You only need to open LinkedIn to see British, German, and Nordic entrepreneurs openly voicing their frustration with the restrictions and governance burdens they face. There’s a reason so much talent ends up moving to the U.S.

And then there's India. It’s fascinating for me to watch how entrepreneurship has grown there in just the past couple of decades. Twenty years ago, when I was studying at IIT and then IIM, entrepreneurship was a fringe career choice. Working for a startup?

That was something that would make your parents extremely anxious. The self-employed were shopkeepers, paanwallahs (local corner shops selling small items), small business owners, people who worked hard but weren’t seen as “entrepreneurs” in the modern startup sense. No disrespect to them at all, but for a middle-class, educated Indian family, the ideal was stable, secure employment. Ideally a corporate job, or even better, a government job.

So to see this shift in India over the past 10 to 15 years, it honestly staggers me. Today, a lot of young people come straight out of undergrad wanting to start companies. That level of risk-taking simply didn’t exist in my batch.

It really is fascinating. Venture capital has created opportunities I couldn’t have imagined back when I was in India. What India has going for it is its scale, it's a large, unified market with a broadly consistent legal framework. And honestly, in some ways, that puts Europe at a disadvantage.

This might be a controversial take, but I see Europe as made up of a lot of subscale countries, markets that, on their own, just aren’t big enough. It creates a very different kind of challenge for European entrepreneurs compared to their counterparts in the U.S. or India.

Take an American entrepreneur, for example, when they build a business, they don’t really have to think about expanding into a new market for at least five to ten years. And I’d say the same goes for India. If an Indian entrepreneur has a solid business and a good model, they don’t need to think about crossing borders right away.

European entrepreneurs, on the other hand, often don’t have that luxury. Unless they’re in France or Germany, founders, especially those from Central or Eastern Europe, have to think about going international almost from day one. Either they need to start selling in the U.S. or find a way to operate across multiple borders within Europe. That’s a very real constraint.

China probably falls into the same category as the U.S. and India, one large, unified market. But the difference with India is that a large portion of the population still doesn’t have the disposable income to support the kind of consumption-driven business models that work in the U.S. or Europe. So even though the market is big, you can’t apply the same playbook.

A great example of this is eyeball-driven models. In India, you can rack up huge numbers of daily active users and app downloads, but you can’t necessarily monetize them. That’s not the case in the U.S., Europe, or even China, where consumer purchasing power is higher, and monetization is more straightforward.

In India, the orientation has to be different. You need to focus on frugal innovation, on affordability from day one. It’s not about building for luxury consumption; it’s about removing friction for access and affordability. That shifts the kinds of problems Indian entrepreneurs are trying to solve. They’re not creating new offers for discretionary income, they’re figuring out how to stretch existing income further or unlock value in a different way.

So that’s the major distinction I see. Beyond that, I still hold the view that venture capital and entrepreneurship are most deeply synonymous with the U.S. Each ecosystem will find its own way to support innovation and founders, and that’s a good thing, but the U.S. continues to lead in terms of institutional support and risk appetite.

As a global investor, I find that incredibly enriching. Being able to spot differences across ecosystems, in the U.S., China, India, Israel, that’s not something you get to do if you’re a specialist investor. Specialist investors have their own strengths, of course. But the ability to observe macro trends across markets, that’s something I’m genuinely grateful for in my role at Syngenta Group Ventures.

Disruption Theory

Rhishi Pethe: In your original piece, the one from 2020, you talked about disruption theory. According to the theory, disruption usually starts at the low end of the market. You also brought up India. Do you think India has the right conditions for the next big disruption in agriculture?

Yields are relatively low, access to information is limited, and there are a ton of structural challenges. It checks a lot of the boxes for where disruption should happen. What’s your take on that?

Shubhang Shankar: I'll share a few thoughts. I think Indian companies can, and probably will, eventually dominate in purely software-driven businesses. The reason is simple: when you design for an Indian farmer or an Indian customer, you have no choice but to design efficiently. There’s no buffer of affordability, so you're constantly forced to eliminate costs.

And once you’ve stripped things down, made the product lean and cost-effective, and still managed to deliver real value, you’re in a great position to serve users globally. Why not?

One area where I see real potential is satellite or data analytics. If India continues launching low-cost satellites, which it already does regularly, there’s no reason we can’t offer those capabilities to customers in the West. The infrastructure is already there.

Similarly, take a company like Niqo Robotics. They’re building solutions tailored for small farms in India. If they get it right, they could expand to a wide range of customer segments, not just in South Asia or Southeast Asia, but even in the U.S. So yes, I do think the potential for disruption coming from India is very real.

Now, as for the timeline, when it will happen, and who will lead that wave, that’s harder to predict. Because the first step is still building solutions that are truly fit for Indian farmers. Only after that can we start thinking about scaling globally.

The potential is definitely there. Whether it’s realized soon, and by whom, I really can’t say. I don’t see a specific company right now that’s clearly poised to be a global winner. And maybe that’s just the nature of agriculture. It’s such a local, fragmented industry that becoming a global player is inherently difficult.

That’s why I think the best opportunities will likely come from areas like satellite tech or data analytics, places where the solutions don’t need to be hyper-localized. That’s where we might see India driving real disruption.

Rhishi Pethe: UPI is a good example, right?

Shubhang Shankar: UPI is a fantastic example. It was set up for very cost-conscious customers and today it is being rolled out internationally. But that is exactly the kind of innovation that I think can and should come from India which can be a global winner.

Rhishi Pethe: When I was in college in India we had an agriculture department in my university and we actually used to make fun of them.

Shubhang Shankar: Yeah, same here. Agriculture was something we all ran away from, especially in India. You and I are both Indian, and you know how it is, agriculture wasn’t seen as aspirational.

So in a way, it’s kind of ironic that we’re now working in this industry and actually enjoying it. It just goes to show, you really don’t know everything at 21 or 22.

Advice for new graduates

Rhishi Pethe: I want to zoom out a bit here. Let’s say someone’s graduating right now, and they come to me with a really basic question: “Hey, I just got my degree in [X or Y], should I work in this space or not?” And honestly, I struggle to answer that.

If you look at the big picture, population growth is already slowing, and it might actually decline in the future. So when you take that macro view, it raises real questions about where the opportunities are, what kind of impact you can have, and what problems are even worth solving. What would you tell someone just starting out?

Shubhang Shankar: I mean, Elon Musk is doing his best to make sure population decline doesn’t happen, we’ll see how that turns out.

Let me give you a bit of a copout answer here, because I’ve been at Syngenta for 10 years now. And if you had asked me right after graduation, “Shubang, do you think you’ll be working at an agricultural inputs innovation company 15 years from now?” I would’ve said, “Absolutely no chance.” None.

The point I’m getting at is, careers are incredibly nonlinear. Life takes you in directions you can’t even imagine when you’re 21, or 22, or 25. So I find it really hard to give anyone a definitive answer like, “You should go into this sector or that one.” And it’s not just me, I’ve seen it with so many of my peers. A lot of them ended up in places they never thought they’d be.

At 21, most of us thought we’d be consultants or bankers. And sure, some of us became career consultants or bankers. But others took different paths and found satisfaction later on in totally unexpected areas.

So here’s how I think about it: if by the time you’re 35, you’ve figured out a few areas you don’t want to work in, that’s a win. And if by your early 40s you’ve landed somewhere you do want to be, I’d say you’ve won at life.

When someone young asks me, “Where should I work?” I tell them, “You don’t have to decide right now.” The idea that the job or company you commit to at 21 determines your entire career and retirement, that era’s gone.

So focus on getting experiences. Whatever role you’re in, whether it’s a startup, a big corporate, a scale-up, give it your best. Learn what you can, and stay open to where life might lead you. Opportunities will show up, both internally and externally, and your path will start to take shape.

All that really matters is that each year, you feel like you’ve grown a little, picked up a bit more experience, developed new skills. That’s progress.

So when young people ask me, “Why should I work in AgTech?” I tell them, “Honestly, I don’t know.” I don’t even have a specific reason why I continue working in AgTech. Go be a banker. Go work in marketing. Go join a startup. It doesn’t really matter, because the truth is, in your first 10 years, you can’t really make a mistake in your career.

Whatever you do, you’ll either enjoy it and lean into it, or you’ll figure out quickly that it’s not for you, and that’s fine too. You’ll pivot, and you’ll be better for it. So for those first 10 to 15 years, just stay open. Explore. Let your career evolve.

Some of us spend a few years at a company and realize we want to become entrepreneurs. And often, we end up solving problems we never imagined would interest us. If you polled a bunch of AgTech founders and asked them how they got into the space, I’d bet very few could draw a straight line from their past roles to what they’re doing now.

So that’s my answer. It might not be the most satisfying one, but honestly, it’s the best one I can give.