Metrics, Unit Economics, and Business Models

Smaller tractors, greenhouse robots, and context dependent business models (edition 176)

Programming Notes:

There will not be a weekly analysis email next week, but there will be a “Last Month in AgriFoodTech” email on December 1, 2024

The 15% discount on annual subscriptions is still available.

Happy Thanksgiving, if you do celebrate!

This week’s edition includes three separate but related stories, about the right metrics to compare performance, the right data to think about unit economics, and the right business model for the context.

- What is the right metric to measure equipment performance? It draws on comments from Feroz Sheikh (CIO of Syngenta), Craig Rupp (CEO of Sabanto), and how smaller equipment can redefine productivity.

- How did Four Growers think about unit economics, and where does unit economics need to be for tomato picking robots?

- What does Jaisimha Rao (CEO of Niqo Robotics) think about different business models based on the context?

AgTech Advisory Collective

The publisher for SFTW and product & technology strategy firm, Metal Dog Labs has joined the AgTech Advisory Collective. The collective is a global network of independent deep experts in AgTech. The independent consultants have expertise operating in Australia, the US, Canada, South America, and Europe. The collective is meant to provide deep industry specific advisory services, which large consulting firms cannot. The collective members have experience across product, strategy, marketing, go-to-market, pricing, product development etc. Do check out the collective’s website, and get in touch.

A map of the AgTech Advisory Collective and its strategic partners.

Right metric to measure equipment performance

During my “SFTW Convo” with Feroz Sheikh (Nov 13, 2024), Group CIO and CDO for Syngenta Group said the following about the future of agriculture. (highlights by me).

One of the other things I think is going to happen is AI will start to make the machines more autonomous. So we will start to see a little more of autonomy at precision. And when you take away the human factor, when the machines are operating autonomously, then you can imagine a sci-fi world of a swarm of robots operating in the field 24 x 7.

Then you don't need to have a very heavy machine that goes out in the field once every four weeks and has to spray a broadcast at that time. The autonomous machines can operate in the field and take an action instantly when they see a thing. So I think some of those can possibly be the future where we'll see novel practices, novel agronomy come into practice enabled through technology.”

In edition 143. Salinas, we have a problem (Sept 25, 2003), I had talked about a swarm of autonomous equipment, how they will be managed, and how what it means to farm will change. (highlights by me)

The notion of what it means to be in agriculture will change over time. You could be a “farmer” and work in a warehouse. (You could be a farmer, and work in a network operations center.) Even in broad acre production it'll change because as autonomous equipment and automation takes over, what it means to be a farmer will change.

The operations center owns and operates a fleet of equipment, which includes autonomous planters, autonomous selective sprayers, semi to autonomous scouting and spraying drones, autonomous harvesters, which are supplied with inputs like seed & chemicals, biological products, from a regional distribution center.

Craig Rupp, CEO of autonomous equipment startup Sabanto and a man with an opinion on everything, made a similar point last week. His contention is we have peaked in horse-power and heavy machines are causing agronomic damage due to compaction.

I believe we have peaked in horsepower. As autonomous technology matures; I believe horsepower will head in the other direction.

It is difficult to measure the economic impact of compaction on soil. According to a literature review done in 2020, median of 21% crop yield reduction for the next 2 yr for land areas impacted by deep wheel-traffic compaction during the 2019 harvest, with longer-term residual effects on crop yield reductions can and do occur but tend to be less than 5% and occur during inclement weather years.

Smaller equipment will redefine productivity

The consolidation of farmland spurred the design and development of ever larger equipment, and the presence of ever larger equipment spurred the consolidation of farms into larger farms. When we considered all the other costs associated with running a tractor (labor, operations, time, etc.), a larger piece of equipment was much more efficient from a financial and timeliness perspective for large operations.

Craig believes economics will accelerate the transition to smaller equipment. For example, John Deere’s 9RX 830 weighs 84,000 lbs and retails at $ 1,500 / horsepower, whereas a 100 horsepower ROPS tractor retails at $ 675 / horsepower, and weighs 7,000 lbs. The smaller tractor has much less of an issue with soil compaction. Craig does simple math to illustrate a point. For the cost of an 830 HP tractor, you could buy eighteen 100 HP tractors and get a total of 1800 HP.

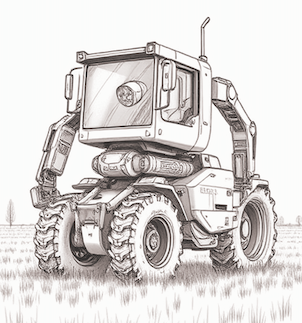

Future vehicle concept for a small multipurpose tractor (by Eeshan Inamdar)

This is an interesting way to illustrate a point, though the math is only directionally correct, as all horsepower are not equal and they are only part of the overall economic equation. You need a certain minimum number of horsepower to do certain activities. For example, an average human can generate 1.2 hp and 0.1 hp over a longer period of time. The economic cost of employing 8,300 (830 hp / 0.1 hp) humans instead of a 9RX 830 would not work operationally or economically.

Even though directly comparing cost per unit horsepower between a big ass tractor and a swarm of small tractors, tells an interesting story, it is not the full story. Even if you went with 18 tractors, you will need 18 drivers, and depending on what operation you are doing, you will need additional supporting equipment and infrastructure.

The right metric is not dollars per horsepower. This is the input into the operation. The right metric will be some combination of dollar and time per unit of output, which is adjusted for risk of each type of operation.

The unit of output could be bushels or acres (this is also an input but is closer to an output). What is the operational cost of working an acre of a particular operation or harvesting a bushel of soybean? The costs will have to include the equipment costs, labor costs, operational costs, management costs, maintenance costs etc.

Given the high non-equipment costs of labor, operations, management, and maintenance, and the timeliness needed for certain operations, a massive large tractor like the Deere 9RX 830 is economical for very large commodity row crop operations, when we use the right metric to define it.

But smaller equipment will redefine productivity, and will change the economic equation.

For example, the labor cost is reduced drastically, due to the use of autonomous equipment, but it increases the cost of managing a fleet of smaller equipment, servicing it, and

Superior network connectivity, fleet management through software and a network operations center, will reduce the operational costs of managing a large number of equipment vs. a big-ass tractor. We are nowhere close to this happening, but it could happen in the future.

Autonomy will allow the equipment to work longer (within fuel, and/or battery constraints), stay in the field longer, improve equipment utilization rates, and will act quickly when something does not seem right.

A swarm of smaller equipment does not have a single point of failure, and so it provides higher resilience and reliability to farmers. When you are managing a fleet of smaller equipment, adoption of new technology becomes easier, as you can replace or upgrade a few units of your fleet, run some experiments, and then decide to upgrade your entire fleet.

Future concept of a swarm of robots managed from a control tower operating in a field (by Eeshan Inamdar)

We will have to have a good sense of the user experience and the right metrics (at least order of magnitude wise) to understand what has to be true for certain inflection points to happen. Understanding the potential shape these changes can take is critical to prioritize projects, and investments.

Pick the right metrics for comparisons with the right alternatives to make decisions.

Make the economics work

As the attention in AgTech has shifted from growth to profitability, companies have to really try to understand the unit economics of their offering.

Unit economics are the direct revenues and costs of a particular business measured on a per-unit basis, where a unit can be any quantifiable item that brings value to the business. Calculating unit economics makes it easier to forecast things such as break-even points and gross margins.

Does your offering create measurable value and can you capture some of it? Can you deliver your product or service, in such a way that every unit you sell is profitable. It is very important to understand this as it has a direct impact on your go-to-market strategy, and decides which type of customers you can try to sell your product.

For example, Four Growers, which builds robots to pick fruits like tomatoes, recently raised a $ 9 million Series A round led by Basset Capital with participation from other VCs bringing their total to $ 15 million for venture funding. The production of US grown tomatoes has dropped over the last 20 years as the labor costs have soared.

When Four Growers looked at the unit economics of vertical farms, they quickly realized the extremely challenging unit economics of vertical farms, and decided against building tech for vertical farms. Greenhouses are much better suited for deploying robotic technology for harvesting. Greenhouses have a couple of things going for them.

- The environment is much more controlled compared to an outdoor farm. The technology becomes easier to develop and deploy.

- Harvesting happens multiple times during the year, and the cost of the robot can be spread across multiple harvest runs.

- Green houses can be closer to their customers, which helps the unit economics in terms of the total landed cost for each tomato.

Four Growers’ robot GR-100 has 5x faster picking speed than the next best alternative, can harvest up to 43 kg per hour of cherry and grape tomatoes, and is 98% accurate in knowing which tomatoes to pick based on ripeness detection using stereo cameras.

Based on a time study done by the University of Florida in 2020, a picker can pick 20 buckets per hour, with each bucket holding 30-35 lbs of tomatoes. This comes to about 30 x 20 = 600 lbs ~ 270 kg / hour, which is more than 6 times faster than a GR-100 robot. The time study was done in an open field system.

Image generated by DALL-E “Inside of a tomato greenhouse managed by robots and drones”

The cost of H2A workers in the United States is between $ 20-30 per hour. The operational cost for the tomato picking robot should be a sixth of a human, if a human picker is 6 times more efficient on a per unit basis.

The calculation is not that straightforward.

A robot can work much longer than a human in a given day is potentially equally or more accurate than a human to judge the ripeness of a tomato, there are limited training requirements for the robot as compared to a human, we don’t have to worry about robot health and safety (other than it harming other humans in the vicinity), and the robot will always be available.

If we factor in all of these conditions, we can get a more accurate cost of picking a unit of tomatoes (bucket, lb etc.) which meet the specified quality criteria in terms of ripeness, color, and firmness.

As a robotics provider, one should be aware of all the elements which go into the unit cost of picking. It will make your conversation with your customer that much easier, as you can show them where you are, what are the levers to push costs down, and make the unit economics work.

Understand the unit economics by considering all the factors.

Make the right business model work

Tim Hammerich did a fantastic interview with Jaisimha Rao, CEO of Niqo Robotics at FIRA and it came out earlier this week on the Future of Agriculture podcast.

Jaisimha explained the go-to-market strategy and business model for precision spraying for India is a leasing model. The farm sizes in India are very small (1 to 2 acres). It does not make sense for a farmer to buy an expensive piece of equipment like Niqo Robotics (roughly $ 250K per unit).

Many of these small farmers are serviced by local service providers, who are entrepreneurs. You can think of them as one person or a small retailer / dealer in the US. Niqo leases the precision spraying robot to the entrepreneur (called a VLE = Village Level Entrepreneur) who provides services to a few hundred farmers.

The incentive alignment works well as Niqo gets an on-the-ground sales and service delivery channel, the VLE gets additional business during the lean period between planting and harvesting, and the farmers get reduced input costs and timely service through a sophisticated product like Niqo.

When Niqo Robotics is working with farmers in the US, the business model changes as the number of acres managed by the farmer are much higher in the US than in India. The risk of not being able to access a thinning service in a timely fashion for lettuce growers is fairly high. They want to outright own the equipment

When I wrote about Farmwise and their business model, “Scaling Innovation: Farmwise” (May 22, 2024) (highlights by me)

Most robotics companies in the specialty crop space have moved from robotics as a service to a grower purchase and operated model. Outright ownership by the grower is a good risk mitigation strategy for the grower, given the importance of timeliness of operations like weeding, etc. If a grower owns the equipment, they are guaranteed to have the equipment available when they need it.

Niqo follows a similar business model, but they work with dealers. Their business model requires enough margins for the dealer to be able to sell the equipment to the farmer (or lease it to them if they so choose), and then have the capability to support the grower, if and when the need arises.

The incentive alignment seems to work well on paper.

Niqo sells the robots to dealers, the dealers have confidence they can sell these robots to growers and still make enough margins, while being able to support the growers in a timely manner. Niqo gets access to the sales and marketing resources of the dealer.

The growers get a relatively low price (compared to some of the other robotic equipment out there which run in the 7 figure range), and they get to own the piece of equipment, to reduce the risk of having access to it in a timely manner.

Find the right business model with aligned incentives