Precision and Structural Shifts

Will Economically Viable Precision lead to Structural Shifts?

There are two AgTech Alchemy events coming up in the next 10 days. There will be one event hosted by Walt Duflock in Davis on October 24th (registration link), around FIRA. There will be another event hosted by Walt Duflock, Sachi, and I in Berkeley on October 30th (registration link). I will be at FIRA on Tuesday next week. Drop me a line, if you would like to meet in person at FIRA on Tuesday (October 22nd).

If you are on a free tier, and sign up for an annual subscription for SFTW in the next 3 weeks, I am offering a 15% discount.

Now, on to this week’s edition.

Economically Viable Precision & Potential Structural Shifts

In the classic science fiction comedy, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, the earth is a super computer designed to come up with the Ultimate Question to the Ultimate Answer.

The earth was an intelligence device with life forms on it designed by the Magratheans.

In a tragic (?) twist of events, the intelligence device (earth) is destroyed by the Vogons with the flimsy excuse of building a hyperspace bypass!

Today we are worried about a reverse case of rogue Artificial Intelligence taking away all of human jobs, and ultimately killing us all in the worst case. On the other hand, there are many others who believe AI will lead to explosive growth and prosperity in the coming years. (Explosive growth is defined as annual real gross world product (GWP) exceeding 130% of its maximum value over all previous years.)

As with most things in life, we will land somewhere in between these two extreme scenarios. I am less worried about AI destroying us or our way of life. I am more worried about geopolitical conflicts and wars, and climate change creating difficult situations for a large section of the population.

If we want to make the analysis a bit more tractable, we can look at how different technologies have impacted a field like agriculture and food in recent history.

Can we draw any parallels with AI in general, and generative AI in particular, and do we believe GenAI could bring about structural shifts in the industry?

Power for the people

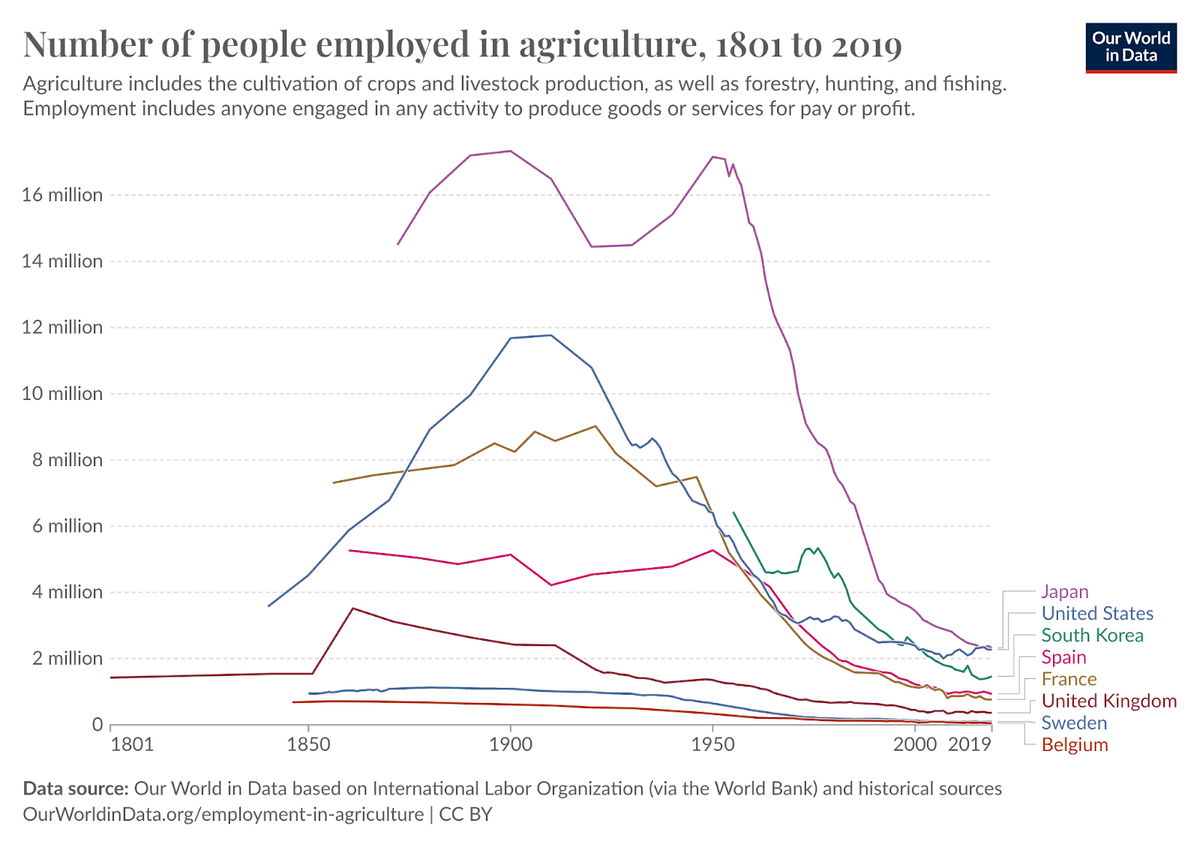

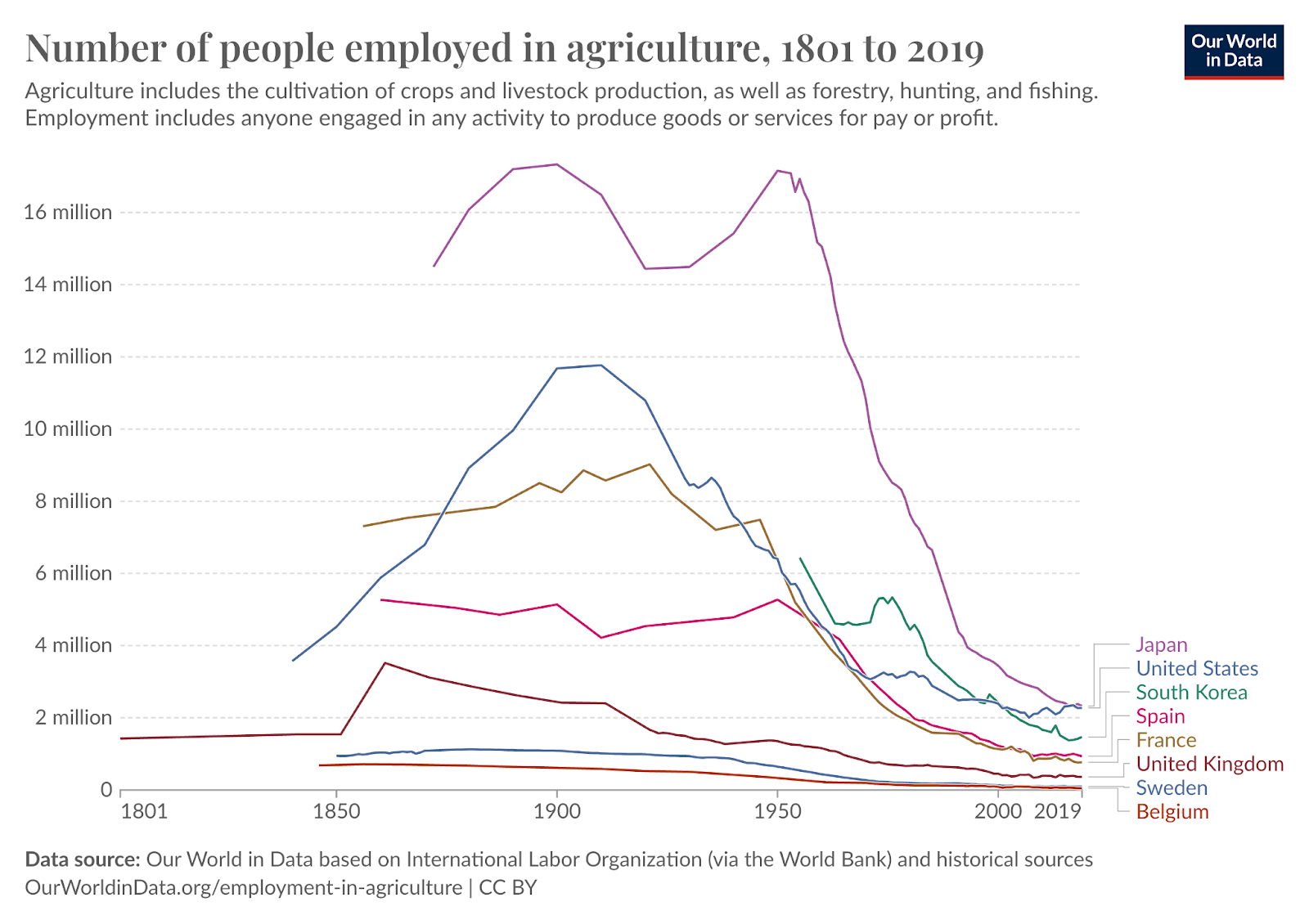

Many of you must have seen the chart of the number of people employed in agriculture, and the dramatic drop in most countries. The point in time when the drop started is different for different countries, depending on when general purpose technology like tractors became more mainstream.

The rapid drop in employment in agriculture from 50% was driven by power, in terms of tractors, combines, harvesters etc.

Tractors were (and are) amazing in terms of what they can do. If we look at some history of the invention and adoption of gas-powered tractors, based on Neil Dahstrom’s history of John Deere. (highlights by me)

In 1892 in the tiny village in Northeast Iowa, John Froelich (1849 -1933) invented the first successful gasoline-powered engine that could be driven backwards and forwards.

Froelich and his blacksmith Will Mann came up with a vertical, one-cylinder engine mounted on the running gear of a steam traction engine – a hybrid of their own making. They designed many new parts to make it all fit together, but it finally was done.

John Froehlich’s tractor (Image source: Neil Dahlstorm website)

In 1914 the first Waterloo Boy Tractor, the Model “R” single-speed tractor, was introduced. Farmers liked it and within a year sales reached 118.

Ford and its competitors like Deere and Case quickly realized that a lighter and more maneuverable tractor could perform a wide variety of farm tasks. Competition between companies for the tractor market unleashed many small improvements like rubber tires, power lifts, and the three-point hitch, which continuously leveled uneven ground as it ploughed.

If we go back to history from Neil Dahlstorm, the gas-powered tractor had an impact immediately.

That fall, an engine, a J.I. Case threshing machine, and a fleet of cooking and sleeping wagons, were shipped to Langford, South Dakota. Over the next fifty days, the sixteen-man crew threshed over 62,000 bushels of grain, primarily wheat.

A “dominant design” for tractors emerged in the late 1930s, and tractor production peaked in the United States around 1950.

It took almost four decades from the invention of the gas-powered tractor to get to a dominant design, and it led to a rapid drop in the number of people employed in farming as it was easy and most importantly economical to replace humans and animals with tractors for power requirements on the farm.

It made consolidation of farms possible, and so farms became bigger and fewer. Even today, even if horses are rarely used for farm work, we still use “horse power” to indicate the power capacity on most engines.

Is AI different from gas or steam powered innovation?

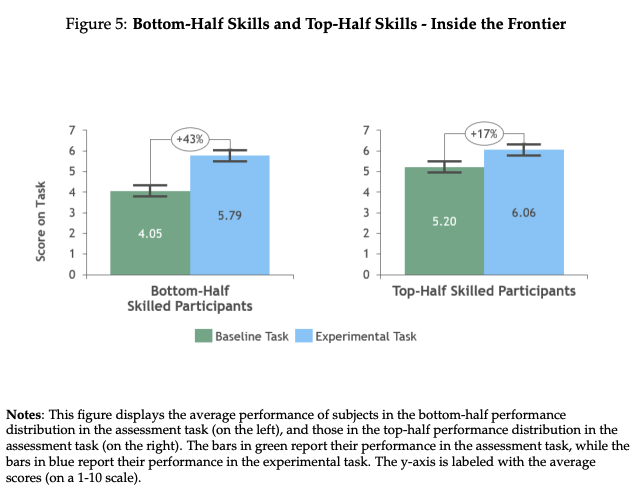

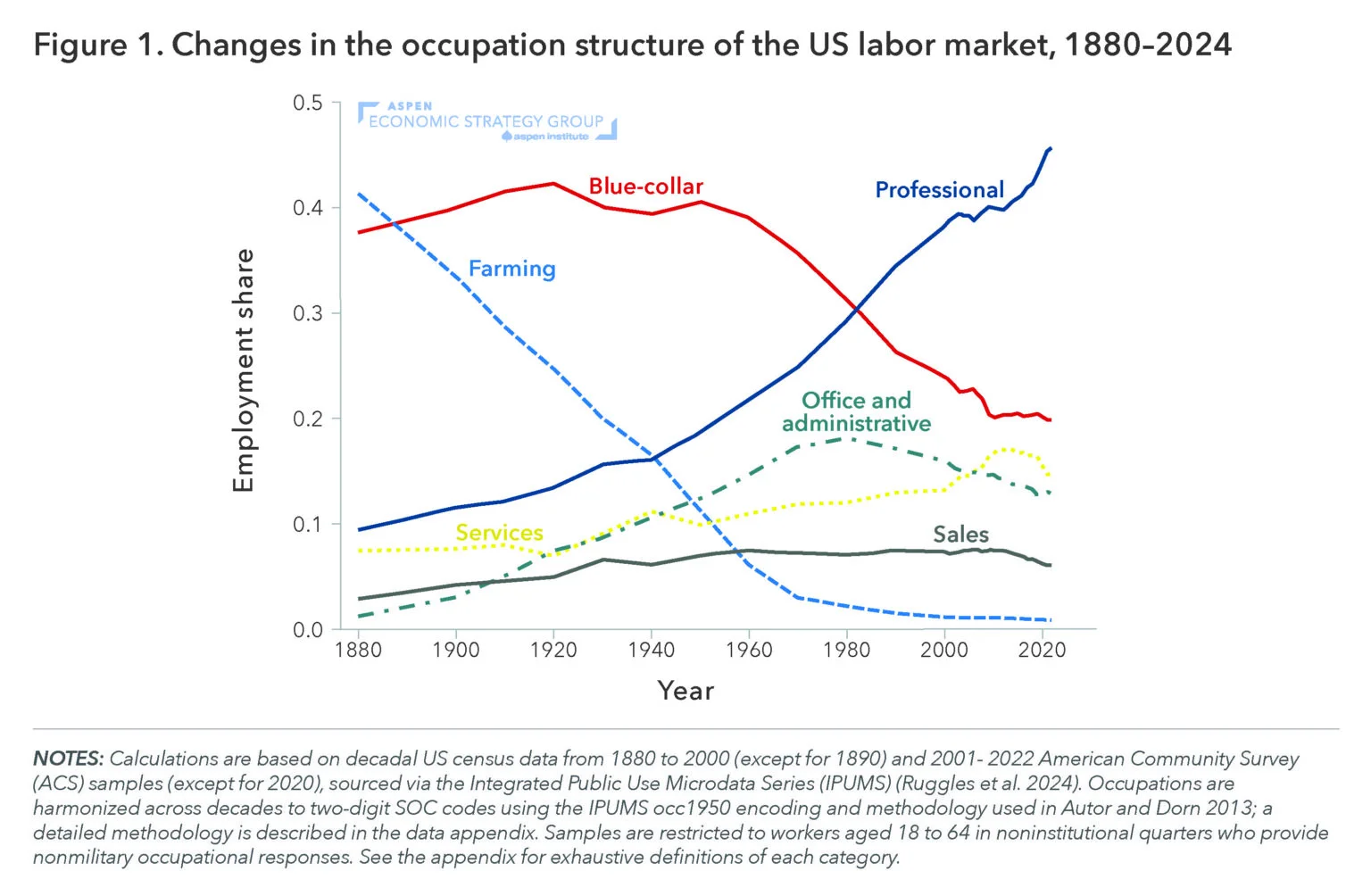

To answer this question, the Aspen Economic Strategic Group published a research paper in October 2024, titled “Technology Disruption in the US Labor Market” to study the effect of different technologies, and especially AI on the US labor market.

The image below is from their research paper, and it shows the percentage of the labor market occupied in different kinds of jobs over the last century and a half. It shows the same decline in farming as the previous chart, a decline in blue-collar workforce percentage driven by automation, and manufacturing moving to more inexpensive parts of the world.

(Highlights by me)

The authors conclude that, with respect to white collar-jobs, AI will contribute to the ongoing decline in back-office administrative jobs and rise in management and business operations occupations. As AI technology improves, innovations like pricing algorithms and automated scheduling may lead to declining employment in sales and administrative-support occupations. On the other hand, while AI helps with certain tasks of professional and managerial workers, the demand for good ideas and cogent analysis of complex counterfactual thought experiments may be nearly unlimited. In this way, at least in the near term, AI is more likely to ratchet up firms’ expectations of knowledge workers than it is to replace them.

One of the big differences with AI powered solutions is that AI is about increased precision than the status quo. AI is competing with the brain power, experience, and decision making abilities of human beings.

In addition to increased precision, AI should be more productive and profitable than the status quo. It is a high bar for AI to beat, especially for agriculture systems which are already efficient (for example, commodity row crops).

Economically Viable Precision for People and Machines

Many of the current methods for weed control include broadcast spraying on crops. Broadcast spraying is not precise. AI can make it more precise by targeting weeds. The precision on its own is not enough, unless the new methods are more precise, equally or more effective, and increase the overall profitability of the farm.

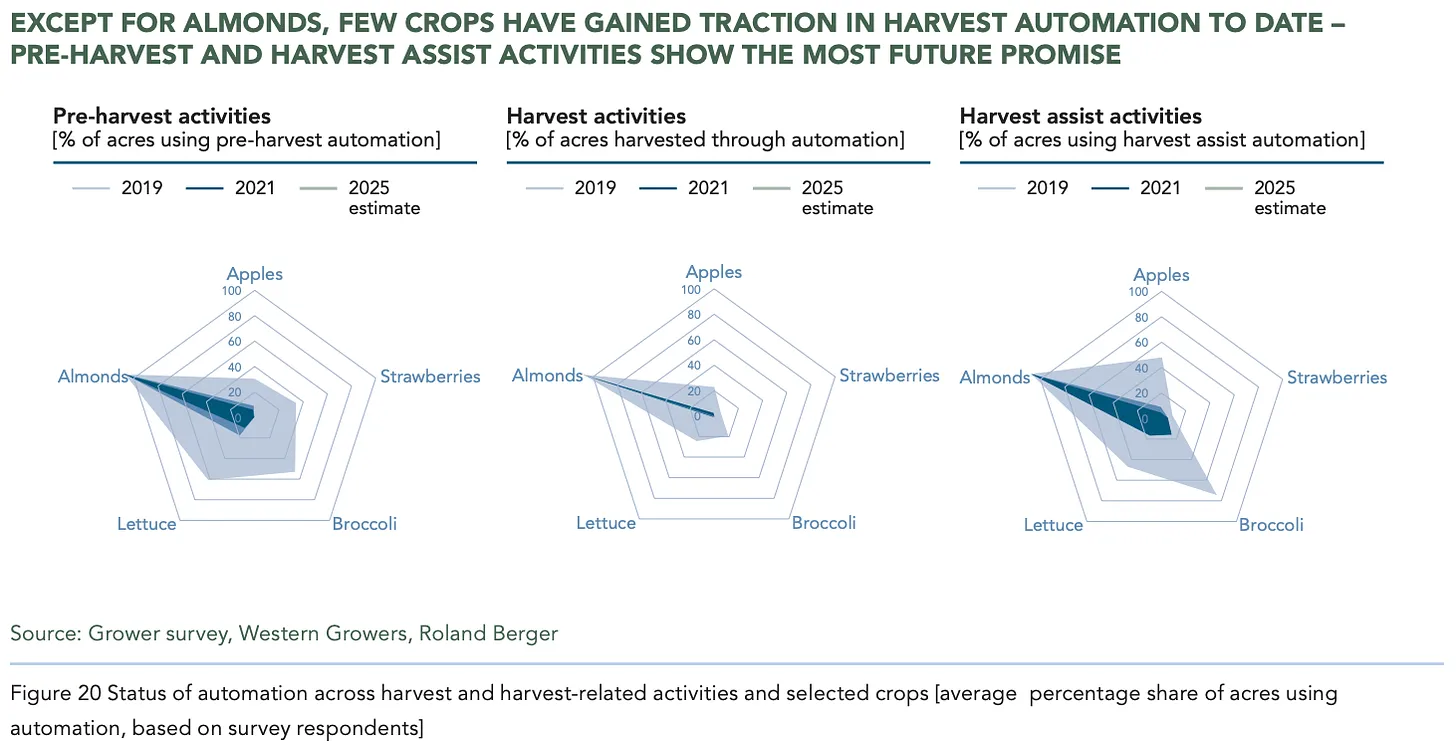

In fruits and vegetables, many crops are harvested by human labor with limited automation. These are often called “last mile” jobs which have not been automated. Many of these jobs (in the US) are filled by seasonal migrant workers, who are getting harder and more expensive to find due to political, economic and social issues.

These workers are extremely skilled at harvesting rapidly, judging quickly what to harvest, and harvesting with a high quality. (low wastage, minimum damage to the product being harvested etc.)

Even though these are considered low skilled jobs, they are cognitively complex, and physically demanding. It is quite hard to teach machines powered by AI to do the same job with the same (or higher) degree of precision, while being economical at the same time.

AI powered machines have to replicate fine motor skills. The machines have to replicate the experience of humans to do the same job. The difficulty to do so is explained by something called the Moravec’s paradox.

Even if we are able to solve these hard problems using AI and computer vision, precision alone is not enough, if it is not economically viable precision.

We saw this during the adoption of gas-powered engines compared to steam-powered engines.

Steam powered farm equipment was around before gas-powered equipment, but even though it solved the power challenge of humans and animals, it was expensive and unreliable compared to humans.

The adoption of equipment on farms did not take off, till it became economically viable compared to the existing options, which was possible due to two complementary technologies - the internal combustion engine and the general purpose tractor.

Going back to Neil Dahlstorm,

According to an article in the Dubuque (IA) Evening Times, a steam traction engine cost $15 a day to operate, while the Froelich engine claimed to run on $7 a day. $2 a day in Waterloo Courier, August 9, 1893.

Over the next year, Froelich showed that his gasoline traction engine could run for half the cost of a steam engine. By the time a company was formed and the engine was put into production, that cost fell by two-thirds, to two-dollars a day.

Walt Duflock, VP of Innovation at Western Growers Association, recently made the same point, when it comes to an operation like picking apples in response to the advanced.farm team picking 24 bins of apples in 24 hours.

It puts the focus on the right metric - picking efficiency. Too often I see automation startups focused on whether or not the robot can do the task asked. But that is not the whole question - it's always can it do the task (table stakes) at a rate that provides competitive grower economics. In this case, the grower is comparing the performance of an apple picking robot with the performance of an H-2A or domestic farm worker crew. The ability to say that your robot can pick a bin an hour for a 24 hour period allows the grower to evaluate that on their metric and the way they think about their business. Meeting the grower where they are is always a great idea.

So precision on its own is not sufficient, we need economically viable precision.

What about GenAI?

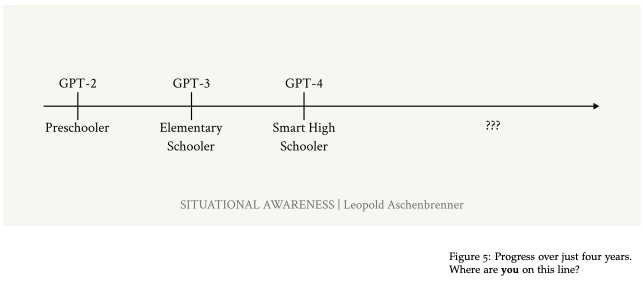

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT have seen rapid advancements in the last 2 years. For example, we have seen orders of magnitude improvement in just four years when we went from GPT2 to GPT4.

Source: “Situational Awareness” by Leopold Aschenbrenner

In spite of this rapid progress, many GenAI projects have struggled to go past the concept or pilot phase in an enterprise context. (This is based on data presented during “The AI conference” in San Francisco in September 2024)

Some of the main reasons for the challenge with pushing GenAI projects from pilot to production are related to precision of GenAI models. This is especially true in a legacy industry like agriculture, where farmers and other stakeholders are used to having a human touch to most of the transactions - whether it is their agronomist, or their seed or fertilizer sales person, or their produce buyer from a grocery retailer.

For many of these businesses, there are considerations around policy, and liability, when it comes to advice or decision making done by a GenAI agent. It is harder to think through and incorporate issues around policy, liability, and bias in these types of models, while still having the trust and confidence needed for adoption.

Generative AI is an extremely promising general purpose technology which already provides productivity boost across a wide range of jobs and tasks. But depending on the task being done, it needs to improve in reliability to build trust and confidence, without introducing massive bias. It is/will be possible through the use of high quality domain specific data, but it still needs to find killer use cases to truly create disruptive change.

Are structural changes afoot driven by GenAI?

What is the level of precision required from a GenAI powered solution to win the trust and confidence of your business customer? It is not sufficient to match human standards due to issues of liability. These solutions will have to be better than humans, consistent, non-biased, and be trust worthy.

Also, will they still require a human touch when making consequential decisions around agronomy, input purchases, or market linkages?

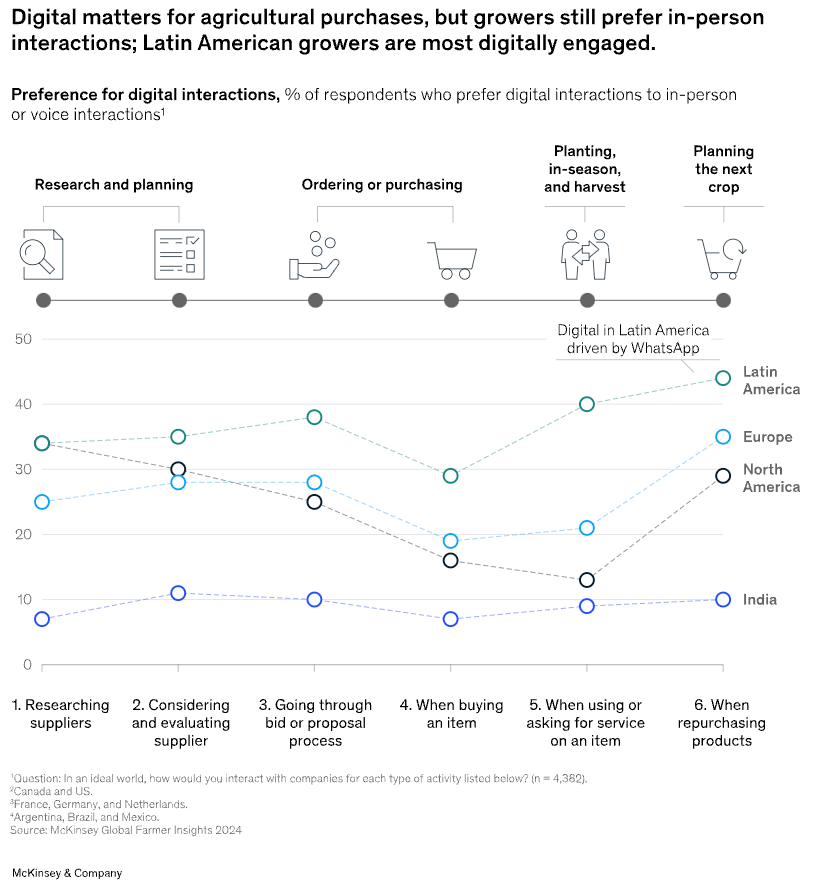

If we go by the McKinsey’s latest Global Farmer Insights 2024 survey, even though digital matters for agriculture purchases, growers still prefer in-person interactions.

Image source: McKinsey Global Farmer Insights 2024

Does this portend some structural changes in the agriculture industry over the coming years?

If and when GenAI powered agents become ubiquitous and can create a high degree of trust and confidence, what would the interaction model be between a customer and the product or service provider?

Is it going to create structural changes in the relationship between farmers and the entities who provide them products and services (for example, your input companies, your equipment dealers, your ag retailers etc.)? If the majority of the analysis support, pricing and product recommendations etc. are off-loaded to AI agents, how can organizations compete with each other? How will farmers' expectations change, when it comes to interacting with these GenAI powered product and service providers?

We need to understand the structural shifts to see if there are going to be any second order effects which have an impact on business models and successful companies.

Should organizations take some of the productivity improvements through GenAI and invest them into improving their customer service (through humans) to provide a different experience to their customers? It feels like organizations using GenAI agents should invest more in their employees rather than less. Finding good people is one of the hardest things to do, especially in a sector with high turnover rates.

For example, Best Buy said in its Q1 2025 (they have wonky fiscal years) earnings call,

Best Buy is harnessing generative AI to enhance its customer service operations and app while increasing training and hours for employees to drive better store experiences. The retailer is giving sales associates more hours than last year to ensure stores are better staffed. A dedicated computing department staff will further enhance the store experience. Best Buy has deployed these specialized experts at hundreds of stores, and plans to add dedicated workers to the major appliances and home theater departments in the summer.

Investing in employees powered by AI agents can be an asymmetric strategy for companies to increase retention and employee appeal, while improving revenue and profitability.

It can help organizations provide a differentiated service to mid to large size farmers, while using the scalability and personalization capabilities of technology to serve the long tail of small farmers.

Is your organization thinking about investing more in human capital on the other side of realizing productivity improvements driven by AI in general, and GenAI in particular?