Rooted Partnerships: How Plants Cultivate Microbial Allies

Tuesdays with Dr. Tuesday Simmons

I am excited to welcome back Dr. Tuesday Simmons for another "Tuesdays with Tuesday" monthly issue. Dr. Simmons will be sharing her perspective on the importance of the soil microbiome to agriculture and the development of new technologies over the next few month. You can read her full bio at the end of this post.

Webinar: AI Ready Earth Observation Data for Agriculture

This webinar, presented by EarthDaily & AgTech Alchemy reveals how AI transforms Earth Observation (EO) data for unprecedented impact. Discover the power of EO x AI, understanding its 25-year role in enhancing yield maps and crop management. Explore cutting-edge innovations like new "AI Ready Data" that deliver powerful insights.

Unlock strategic advantages and new value in agriculture.

Rooted Partnerships: How Plants Cultivate Microbial Allies

The relationship between plants and microbes is so important that many universities group plant biology and microbiology together in the same department, including at my alma mater, the University of California, Berkeley.

Almost every environment hosts a microbiome—the human gut, deep ocean sediments, even the International Space Station—but the partnership between plants and microbes is something truly special. (I will admit, I’m a little biased.)

Last month, I talked about the broader soil microbiome. It’s an incredibly diverse environment, boasting tens of thousands of species in a single teaspoon of soil. As you travel through the soil and get closer to plant roots however, this diversity starts to decrease.

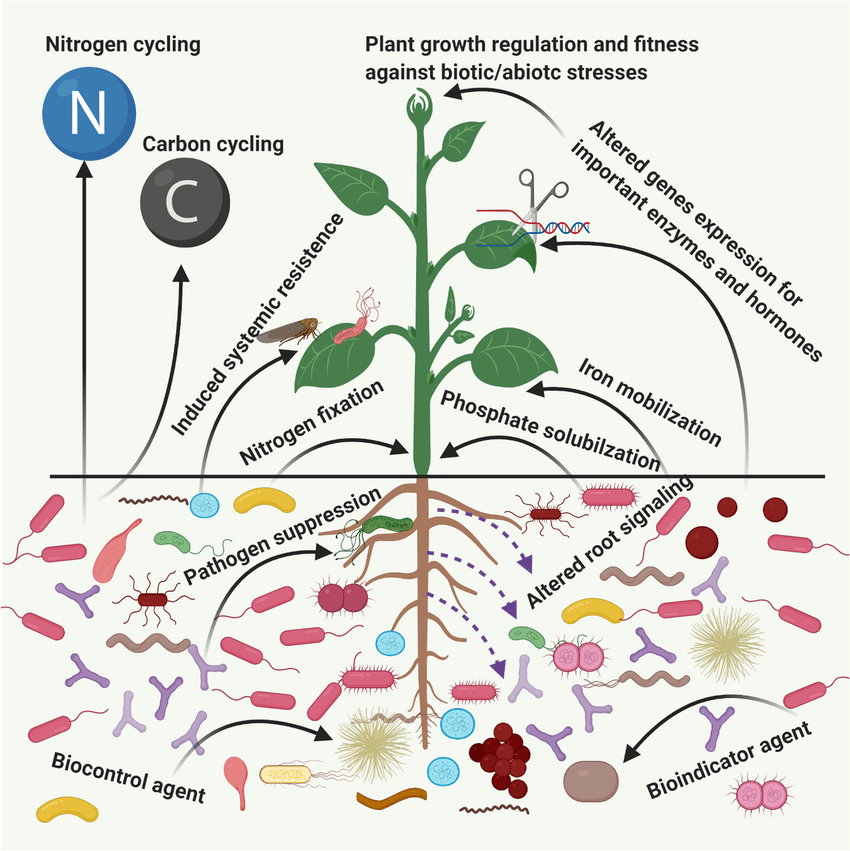

The soil in the few millimeters surrounding plant roots is known as the rhizosphere, and is made up of microbes from the surrounding soil (aka bulk soil) that are “selected” by plants. Moving in even further, the microbial community living inside plant roots (aka root endosphere) is like a private club where the host plant only allows an elite few access. But how do they get invited in?

Silent conversations: how plants “talk” to soil microbes

Human society functions mainly using verbal and visual communication, though we observe other species communicate using other senses. If you took your dog for a walk this morning, they might have left a message for the neighborhood on the corner fire hydrant. If you’re a cat person, perhaps your cat rubbed up against you to communicate affection.

So how do plants and microorganisms communicate? They secrete chemical signals into the soil, which is not too far off from dogs leaving signals that can be smelled by other dogs. When an animal smells something, it’s a chemical signal sent from the nose to the brain.

Plants exude small molecules (collectively known as exudates) into the soil that can be detected by microbes and other plants. These chemicals can share information such as: plant species, age, and how the plant is “feeling” (1).

Plants aren’t just sending messages out into the ether; microbes are also producing chemical signals that are received by plants. For example, legumes form a special relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria that benefits both parties. When the right type of bacteria approaches a legume root, it essentially performs a “secret knock” by releasing a specialized chemical signal that the plant recognizes.

What else can microbes do for plants?

In addition to the relationship between legumes and nitrogen-fixers, microbes are able to perform a whole host of tasks helpful for plants.

- Nutrient cycling is top of mind for most folks in agriculture. While many nutrients are added to the soil in the form of fertilizers, microbes continue to play an important role in macronutrient (N, P, & K) and micronutrient availability. In addition to the famous single-celled nitrogen fixers, Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF) are gaining recognition for their role in phosphorus, water, and mineral uptake (3).

- Plant hormone production: Some microbes known as Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) directly produce plant hormones (like auxin), which could be likened to them screaming “GROW!!”

- Protection against environmental stresses: When plants are stressed out, their root exudates change, which impacts their rhizosphere and root microbiomes. In these cases, they tend to “recruit” microbes that can help them out (4).

- Pathogen protection: Whether it’s an SOS or preemptive planning, plants can get help fighting off pathogens from beneficial microbes.

The dark side: pathogens

I spend a lot of time talking about beneficial microbes because they make up a majority of the species, and they’re underappreciated. However, there’s no arguing the impact that plant pathogens have on agriculture.

They can be transmitted through the air, seeds, or the soil, and are a major yield-limiting factor for crops. Human efforts to combat pathogens include breeding plant resistance and application of pesticides, all the while microbial allies are helping us out underground.

Some specialty crops have resorted to fumigation to eliminate devastating pathogens, but this has a negative effect on the overall soil microbiome. Similar to how a round of antibiotics might be necessary for us while also wrecking our gut microbiome, and we should take care to restore the “good guys”.

A diverse soil/ rhizosphere microbiome is a multi-pronged shield against pathogens. A higher diversity increases competition for resources, which decreases the chances for an invasive pathogen to gain a foothold in the soil community.

Having more species also increases the chance and diversity of anti-microbial production (yes, microbes produce anti-microbial compounds to fight with each other).

So what does this mean for soil management?

I’ll have a full blog post on this topic later on in the series, but the short answer is that agronomists should be keeping up with the latest plant microbiome research (and microbiome scientists should be communicating with agronomists).

Understanding the role of rhizosphere microbes in plant growth can inform nutrient and pathogen management to the benefit of crop performance as well as soil health. Promoting microbial diversity and utilizing specialized biological products can be a key component of an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy.

Plants cultivate microbial partners. We should, too.

The relationship between plants and soil microbes is neither passive nor one-sided. These very different organisms use invisible chemical communication to help each other grow. Plants invite in microbes that perform essential tasks, and high diversity in the surrounding bulk soil can be a shield against disease.

As stewards of the soil, we should be cognizant of this relationship, and notice when it can be used to our advantage to improve crop growth.

References

- Robert, M. et al. Environmental and Biological Drivers of Root Exudation. Annual Review of Plant Biology (2025) doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-arplant-083123-082752.

- Bano, S., WU, X. & Zhang, X. Towards sustainable agriculture: rhizosphere microbiome engineering. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 105, 7141–7160 (2021).

- Wahab, A. et al. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 12, 3102 (2023).

- Ali, S. et al. Plant beneficial microbiome a boon for improving multiple stress tolerance in plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 14, (2023).

Bio of Dr. Tuesday Simmons

Dr. Tuesday Simmons earned a PhD in microbiology from the University of California, Berkeley for research into the effects of drought on cereal crop microbiomes. Post-graduate school, she has worked for start-up companies in R&D, sales, and marketing roles with the goal of effectively communicating the value of cutting-edge biotechnology.

As an Application Scientist at Isolation Bio, she worked with leading gut microbiome researchers to improve high-throughput microbial isolation for academic and pharmaceutical purposes. At Root Applied Sciences and Trace Genomics, she has worked to leverage microbiome research for farmers and agronomists. Since 2024, she has worked as a freelance science writer and consultant.

You should also check out her first post in the series titled "Soil Microbes are Feeding the World" (July 2025)