Connie Bowen: Exploring diverse voices and financing in agriculture

A real expert with real opinions and real experiences

This week’s edition continues the “SFTW Convo” series. It features my conversation with Connie Bowen, Director of Innovation and Investment at AgLaunch. She is also an Investment Advisor with The Yield Lab Europe and a Board Member of The Yield Lab Institute. Connie is a great listener, connector and is not afraid to try out new things. She is experimenting with different financing models. Connie is a big believer in increasing the diversity of voices in food and agriculture systems.

Connie is a big powerhouse of ideas. We couldn’t explore all the topics we wanted to during our conversation. It is very likely that I will do a part 2 with her in the future.

Connie plants hazelnut trees (Image provided by Connie Bowen)

Summary of the conversation

A. Does the VC model work for AgTech? I have been exploring this question quite a bit over the last few months, and Connie provides a great perspective on areas where the VC model works or doesn’t work in agriculture ecosystems.

B. Diversity of financing and voices in agriculture: Connie believes that AgTech is at a very early stage. She is testing the thesis that it requires a blended financing approach. Connie also wants to increase the diversity of voices in agriculture, as she feels that US agriculture is very homogenous from an owner / operator standpoint. She wants to provide voice to women, people of color etc.

C. Data standards and data co-operatives: AgLaunch is exploring the idea of a data co-operative, which goes along with a certain set of data and data model standards. The goal is to not create walled gardens of data and respect data ownership and privacy at the same time.

D. Women in Ag, inspirations and lessons from a lacrosse goalie: Connie talks about her experience of creating the women in ag list, her inspirations and how she connects with people. She also reflects on some important lessons she learnt by playing the goalie position on her college lacrosse team and how they apply to her investing role.

A. Does the VC model work for AgTech?

Rhishi: Thank you for taking the time to have a conversation. How did you end up where you are today?

Connie: I am in agriculture because I love food and I care about impact issues. I worked in kitchens instead of “normal” internships and really considered a culinary career path. I had the privilege of working in a really awesome kitchen in Manhattan (Barbuto - still around, highly recommend the gnocchi and pretty much anything pastry chef Heather Miller cranks out,) . But I was afraid that if I worked in restaurants, I might end up just serving really wealthy people and not contributing to larger global issues. Plus, you can work in a kitchen with an engineering degree, but you really can’t do the opposite, and I’m good at math, so I chose to try the higher ed route, first, and studied engineering.

I went into college very interested in food and gardening, and I got really into controlled environment ag while I was there. I designed a budget greenhouse with an aquaponics system, designed a living wall, and built an aeroponic food computer. . I really was on the indoor ag train, and that kind of led me to startup world (there really weren’t any “established” vertical farms at that time.). That led me to the Venture for America fellowship program, which led me to St. Louis and The Yield Lab.

I started working with The Yield Lab when it was just a $3 million pilot accelerator fund. The Yield Lab was one of the first ag tech specific accelerators and now it's grown into a family of venture capital funds around the world. Through that experience, I got to work with a huge range of experienced agribusiness executives and startup leaders, and I got a landscape overview of what was happening in agrifood tech. And I just fell in love with it.

“I am motivated more by impact than I am by the financial component of investing.” (highlight quote)

I was lucky (and really, I want to acknowledge my dumb luck - my sister’s friend’s dad was hiring, and I was there - most people do NOT have access to jobs in venture, and the network based hiring is problematic) to work with a family office in New York, Grape Arbor VC, which makes angel investments in both startups and funds. The group was formed by a couple of super progressive angel investors and has been relatively early proponent for diversity in venture capital, as evidenced in Ed Zimmerman’s 2014 WSJ Gender Pledge. I managed Grape’s back office as a side hustle, while running the Yield Lab’s accelerator.

That enabled me to compare/contrast “normal” VCs and Ag VCs and see what the docs and discussions looked like for these different groups, which was fascinating.

The more time I spent in agtech VC, the more I felt like there as a gap between “ag” and “tech.” There’s lot of agribusiness in VC, but you rarely see a farmer involved in investment decisions. Adoption of agtech remains frustratingly low, and I wanted to figure out why., That led me to spend some time living out in Willamette Valley and working with Chess Ag Full Harvest Partners, and is a big reason that I’m at AgLaunch today - I think that the hard part of agtech is the “ag” part, and I want to work with ag practitioners to bridge that gap.

Rhishi Pethe: Do you agree with that statement: “Venture Capital does not work for ag?” Why or why not?

Connie Bowen: Depends how you define VC - in 2021, venture capital really means that the company better be able to become a unicorn. You're only hitting home runs or only trying to hit home runs. But technically venture capital doesn't have to be that. You can get greater than 3X returns, without companies having to become billion dollar unicorns.

So, to actually answer the question - there are some ag tech companies that are certainly a fit for venture capital, but there are a lot of ag problems that probably can't be solved by venture capital funding.

An example is robotics equipment. For a strawberry farm, strawberry picking is a pain point. It is bad enough that farmers are throwing money at robots. But you have to change the way you grow strawberries. You have to change the genetics and planting formation of the crop. You have to figure out a hardware system that is probably expensive to develop that has to see and physically remove the berries. And you have to do all of that in the context of a crazy labor system.

In reality, the labor system is used to exploit people and take advantage of cheap labor, and there's only so big of a market for crop specific equipment. And a lot of equipment probably does have to be crop specific, with regional specifications. Each farm is fundamentally different in each region. You do have to design differently for different soil types and different operation types, different orchard formations. That inhibits the level of scaling. I’m NOT saying that we shouldn’t be investing in autonomous ag equipment; it's absolutely necessary as it totally solves a problem.

And it's not that the economics don't work at all. You can create a fund model wherein it's partially debt-based and partially equity-based and you get great returns. But you're not going to get an IPO for a strawberry picking company. You might get acquired or end up with a platform company.

The other dimension to consider is classic disruption vs. other ag technologies. There needs to be thought put into technologies that enable a continuation of the system of agriculture.

A great example is manure management for CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations). Do you want to invest so that CAFOs are less bad and can continue? Or do you want truly disruptive technology, an obvious and overhyped example is cultured “meat,” but another example would be things like Kipster or Vence that scale alternative animal production systems. That's actually changing things.

A Kipster is a more humane way of raising poultry. Image source

Rhishi Pethe: In a VC model, most of the investments will not work and one or two will give you massive returns. And so you think there are no ideas in Ag Tech, which could be massively successful?

Connie Bowen: It does work for some things. It doesn't work for all of the problems that we need to solve. One of the key things that Ag Tech VC is running up against right now, at least on a farm gate level is that adoption rates are terrible. And yet we're plowing money into it. So it is worth taking a step back. Maybe something else needs to change to open the flood gates.

What policies are causing certain things to exist the way that they are? What can drive behavioral change? It is less financial and more theoretical or philosophical. Ag tech companies that are truly scalable cater to corn and soy, which makes sense because that's where the most customers are and the most money is.

But you're not changing anything by doing that. That's just operating within the current system. So what I'm really interested in is what's the ROI for the farmer. But one of the challenges is that it's very difficult to adopt new technology when you're in a “this is how we do it” mindset. There’s this assumption that, between having a funky calendar in terms of cash flow and being a price-taker in the commodity market, farmers aren’t able to invest for the long term.

And if you have a price taker mentality, you're focused on keeping the bottom line lower. And that's the only thing that you can sell to. And there's opportunity there. But wouldn't it be more interesting if we could start to think about how you could expand farming on the ground and change farm markets?

And one of the key ways to do that is to drive more food dollars closer to the farm gate. An important way to do that is through vertical integration. There is corporate vertical integration that further consolidates and is a problem. But there is on-farm vertical integration and value added processing.

I view ag tech as value-added processing. If ag tech is able to retrofit the farm, you are able to go direct to consumers or go through retail channels. It's very difficult to produce at scale and go a hundred percent direct to consumers. So you have to have a blend.

“It's really about what pieces of the margin can you take back that you're not getting today as the grower.” (highlight quote)

Once you can start to do that, you can start to do really interesting things.

In the traceability world, people have been paying more for data or a story bundled with the product they are buying.

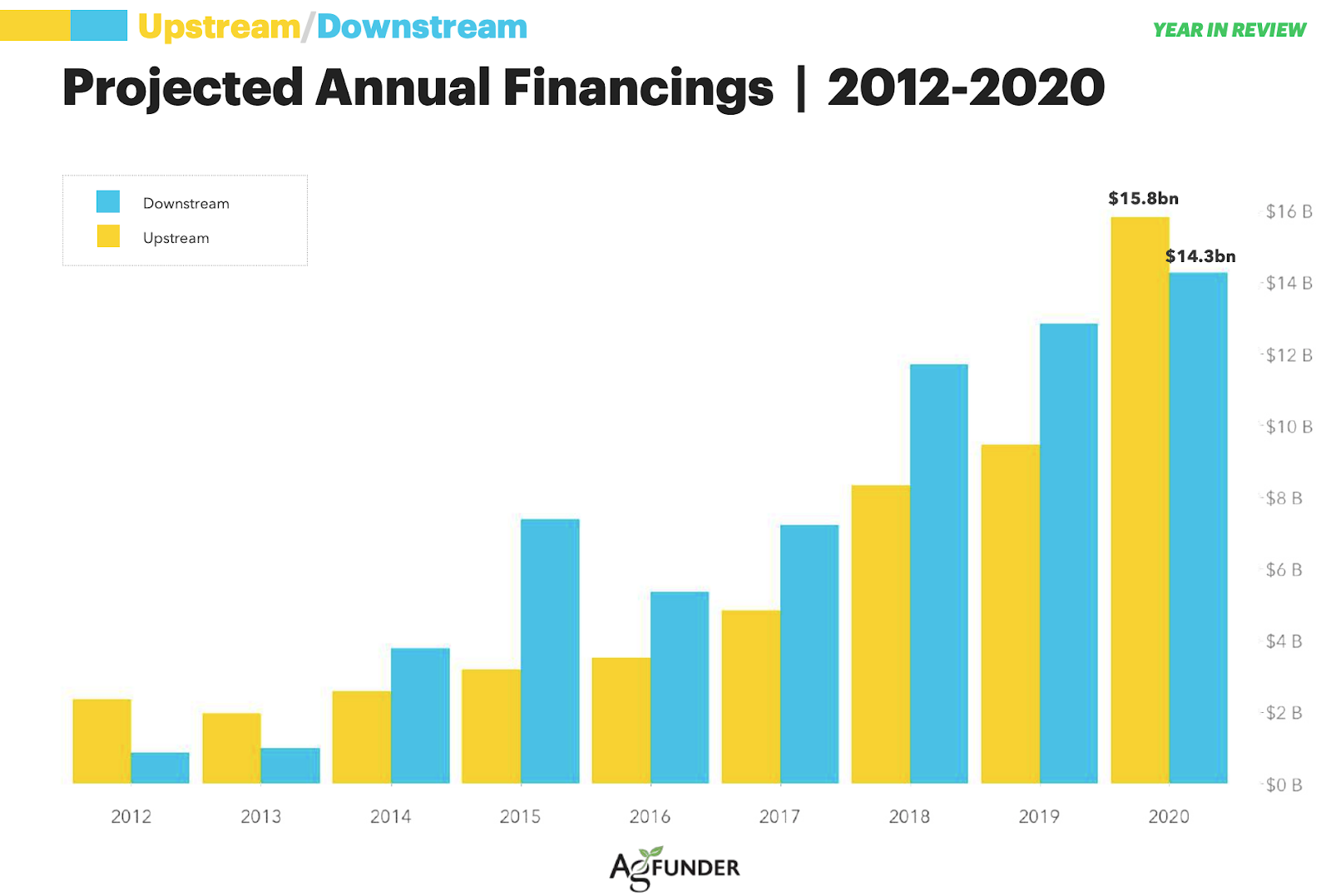

AgTech funding for upstream and downstream has been increasing over the last 9 years. From “2021 AgFunder AgriFoodTech Investment Report”

B. Diversity of financing and voices in agriculture

Rhishi Pethe: I worked in traceability for a couple of years. There is interest in the US, but the willingness to pay is a different thing.

Connie Bowen: You can make it a lot cheaper if you keep it close to a farm, as opposed to trying to figure out all the way at the retailer end. But if you start at the other end, that's a lot easier to know what's happening on my end and I can trace it.

You can get rid of the middleman margins and get a premium. You have the budget to hire someone to handle marketing. Farming is hard enough on its own without having to market your own product, which is why commodities are a beautiful thing. But commodities get us into a bottom line mindset.

“You have to figure out a way to diversify. You can do that only if you can afford it. You can only afford it, if you can control your margin with a blend of approaches.” (highlight quote)

I am trying to drive investment to improve AgriFood systems in an intentionally diverse and equitable way. I go for a run in St. Louis and I cross the street onto the “other side” of Delmar. (The Delmar Divide refers to Delmar Boulevard as a socioeconomic and racial dividing line in St. Louis, Missouri.) And very regularly there are moms lined up at the food bank. We have a very high rate of food insecurity and it's totally racially based. And that's a huge, huge problem. And then there’s sexism..... And then when you get into the farming side, it's very difficult to address these issues because everything is so tied up in land ownership.

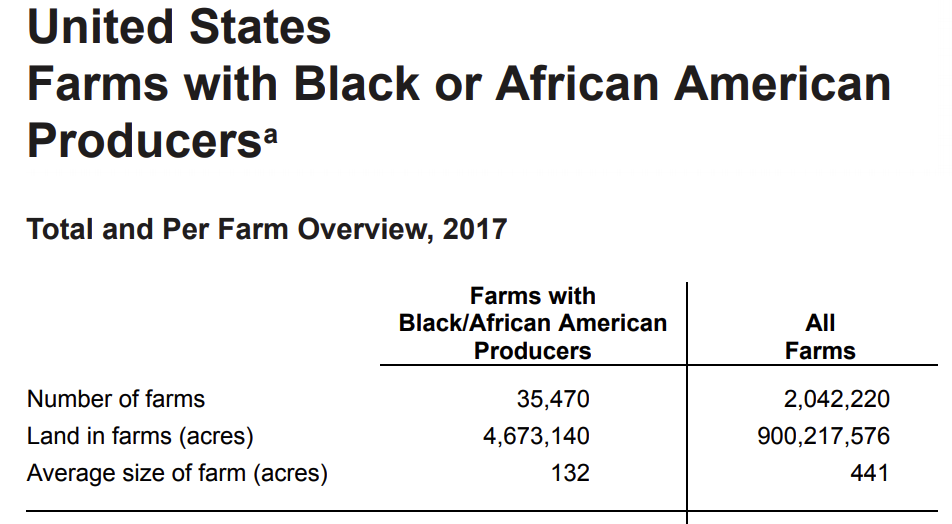

From the 2017 Agriculture Census in the United States: Race, Gender, and Ethnicity profiles. The reports provides data for farms with American Indian or Alaska Native producers (6.5% of farmland), Asian producers (0.3% of farmland), Black or African American producers (0.5% of farmland), Native Hawaiin or Pacific Islander producers (0.1% of farmland), White producers (94.4% of farmland), Hispanic, Latino or Spanish producers (3.6%), female producers (43% of farmland). (There is something wrong with the math in the report, as the numbers add up to more than 100%)

My family owns but does not operate a farm in Iowa. My dad and I had been bugging my grandma who bugs Barry (the farmer managing the land) about planting cover crops for years. And we have had all sorts of programs with the universities that will pay you, but it took years for the operator to change. And when you think about how you do in that land ownership equation is such a key component.

Ultimately, I think that agtechfinance has to improve its understanding of what enables an operation to function. The Farm Credit System does, but it has historically operated in such a way that favorable financing opportunities are historically only available to certain people. But that’s getting better, hopefully. There has to be some hybrid investment vehicle that takes into account land ownership or incentive for land owners or managers and takes into account technology and future markets for that. And really you do have to tie those two things together more than they are today. I really don’t know what the solution is for this “funky fund” structure, yet, but I think that it’s worth experimenting.

Aglaunch is an interesting experimental model, now with some traction. We are a farmer network that seeks to diversify the future of farming in terms of crops and people. It is challenging because most successful farmers are white men. And so we are constantly grappling with that organizationally on how to influence that.

We run field trials and accelerators and pair startups with farmers. The farmers conducting the trials have skin in the game (they are also putting in a lot of effort), and act as advisors. You eventually get to this peer to peer network. It is much more convincing for a peer to say that this thing works.

Rhishi Pethe: Who's funding the startups. Is that the VC model?

Connie Bowen: It’s largely the VC model. We're in a relatively early stage. We would like to see more RBIC funds (Rural Business Investment Program), which are a way for farm credit banks to invest in VC funds. We work closely with Innova in Memphis, TN and Ag VenturesAlliance in Mason City, Iowa. Farmers also put in cash as angel investors.

The AgLaunch thesis is that AgTech is still in very early stages and at a point where we need public and philanthropic funding to get some of these ideas. There are some components of AgTech that should be viewed as pre-commercial e.g. robotics. We are starting with the VC model because it is known. We can’t invest in every company, but we can conduct trials.

Interestingly, the state of Tennessee’s department of agriculture will reimburse farmers for the hard cost associated with field trials conducted through AgLaunch. What if that was in every state? It is not a direct investment, but it enables more bootstrapping.

Rhishi Pethe: Fascinating! So AgTech is in early stages, and so we need a blend of funding sources and representation.

Connie Bowen: Yes the role of AgLaunch is that what we focus on is governed by a group of farmers. And we need blended finance. Most farmers don't know anything about venture capital and angel investing. They do know about investing and starting businesses, but they don’t have the vocabulary, which is a constraint for the venture capital world. It is much easier to think about investing in equipment and land.

I grew up very privileged. I want to amplify other people’s voices and make sure people get heard. I want to work in finance to have power and influence over resources becauseI am a good listener andI am empathetic. I think that I can do a more equitable job of allocating resources than is currently being done. One of the most valuable things I have learned is that you get a lot further by listening and even getting other people to speak up.

The trick is hearing more voices, but the reality is that money talks. We have to figure out how to allocate resources in a way that's probably overcompensating for current injustices. You have to overcome when you're getting pitched by someone, people of certain backgrounds, aren't going to have polished pitches. And so I really try not to count anyone out based off of a bad pitch.

C. Data standards and data co-operatives

Rhishi Pethe: Let us talk about data models and data standards. There are so many data model standards in agriculture. What do you think is going to happen?

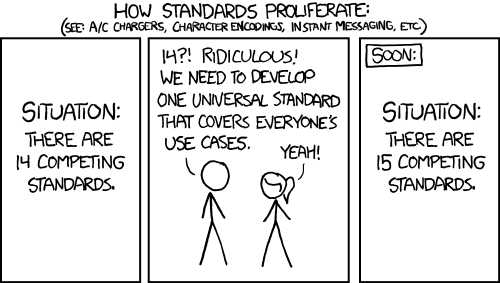

Connie Bowen: We are never going to have a single ag data model - farms are too diverse. At AgLaunch, we're currently working on a Data Commons project. It is essentially a data cooperative, and we are building an ontological model, which promotes interoperability.

Image from XKCD

The Data Commons is essentially a data cooperative that is governed by the AgLaunch Farmer Network. In the Commons, there are basically buckets for each farm and each farmer controls each of those buckets. Our farmers conduct trials with early stage ag tech companies. The farmers control which startup or entity can access their data, and generally only grant access to those companies in which AgLaunch (and therefore our farmers) have skin in the game.

“A data cooperative is a legal construct to facilitate the collaborative pooling of data by individuals or organizations for the economic, social, or cultural benefit of the group.”

This Data Commons creates all sorts of really interesting options. Firstly, it just makes more efficient for farmers to conduct lots of early stage trials. But then digging in further, there are more use cases for specific technologies. Nori is one of the more interesting ones. Participation in carbon markets requires having historical data anda long term contract. With AgLaunch there is incentive to store the data without signing onto that contract. And we're a third party. And we can have a role in verifying things that Nori or tools like the US Cotton Trust Protocol needs. D. Women in Ag, inspirations and lessons from a lacrosse goalie

Rhishi Pethe: You were instrumental in putting together a list of women in AgTech or food. How do you know that it's creating an impact?

Connie Bowen: The list was something that Alison Kopf created a couple of years ago. She just started the list on Twitter and it blew up really quickly.

Look - most women in ag are used to be one of the only’s in the room. I’ve gone to conferences where I’m one of like, ten or twenty women in a thousand plus person audience. That’s insane. It is a problem and we have to do better. I know there are a lot of people who are receptive to having a list, and generally don't have the networks.

I don’t have much of a problem sourcing deal flow from female-founders. At the same time, I have looked at very few companies and heard very few pitches by African-American founders. And that’s a product of my networks. I happen to know a lot of women and women will respond to me because I'm a woman.

Rhishi Pethe: What or who are your inspirations?

Connie Bowen: It’s funny, I think that I initially was driven to work in ag from more of a conservation/sustainability lens, because I was so inspired by the natural world as a kid. I still am, of course - I mean, how can you not be? Even weeds are amazingly cool. But as I’ve gotten more life experience, I'm really just amazed by people. Everyone is dealing with something complicated, and yet, so many people manage to achieve so much. I just want to get on the level of all the amazing people in the world - and that ranges from the guy who has just assigned himself the task of unofficial crossing-guard/morning hype-man in my neighborhood to the game changing professionals like Arlan Hamilton or Serena Williams.

And I very much value creativity and art - I could talk for a few hours about this awesome Millet exhibit that St Louis Art Museum had up last year and its relevance to agtech, but, I’ll spare you.

Rhishi Pethe: You played college lacrosse. What learnings did you have from that experience?

Connie Bowen: Well, firstly, leadership and interpersonal skills - I won’t bore you with the classic things-I-learned-from-sports bit, but, it’s real. I played goalie, and lacrosse is a high scoring game. You get scored on a lot and you have to instantly move on and refocus, then later, when the game is over, reexamine each error and focus on very small adjustments that could have resulted in a save. In VC/startup-world, things fail and you get rejected (VCs fundraise, too) all the time. You have to be able to just keep going, and take the time to examine what went wrong, and what you need to do to get the outcome you want next time.

Rhishi Pethe: Thank you very much for your time and for a stimulating conversation.

Conversation Notes

“Investing with a consumer lens in agrifood-tech” by Connie Bowen, Forbes, March 2020

“Is it meat? Is it milk? Who cares what you call it” by Connie Bowen, Forbes, May 2019

“People are noticing that the food system is flawed. Now what?” By Connie Bowen, Forbes, May 2020.

“End of agriculture” podcast with Sarak K Mock. You can read my fascinating conversation with her from edition 50 of the newsletter.

Women in food and agriculture list.

Delmar Boulevard documentary from the BBC.

Connie Bowen’s college lacrosse record