Eli Pollak: Pathways to Prosperity

CEO of Apollo Ag talks about African Agriculture

46. Eli Pollak: Pathways to prosperity in Eastern Africa

Hi, if you are new here, I am Rhishi Pethe and you became a member of the “Software is feeding the world” community. You will receive this free weekly newsletter (every Sunday) at the intersection of technology and agriculture/food systems. I work as a product manager on Project Mineral at Alphabet X, focused on sustainable agriculture. The views expressed in this newsletter are my personal opinions.

Programming update: I am experimenting with Clubhouse. It was an honor and a privilege to act as a co-host on two panels along with folks like Mark Kahn, Reihem Roy, (both from Omnivore VC), Shubhang Shankar (MD, Syngenta Ventures), PJ Amini (VC from Leaps by Bayer), Vaidehi Ravindran (Lightrock VC), Tim Hammerich (Future of Agriculture), Louisa B Taylor (Agfunder News) and others who jumped on stage to contribute. I hope / plan to continue to do that on Friday mornings and Thursday afternoons, whenever possible. Watch my Twitter feed for topic and co-host announcements.

This week’s newsletter is the “Roots” version, a deep dive into a specific topic. A few weeks back, I had the privilege to talk with Eli Pollak, the CEO of Apollo Agriculture, an AgTech company in East Africa. Eli is a personal friend, and one of the smartest, purpose-driven leaders, that I know.

The conversation went into differences between agriculture issues in the US and Kenya, product management thinking, customer acquisition costs (CAC) and lifetime value (LTV), the impact of AgTech, pathways to prosperity, VC models, entrepreneurship, and a host of other issues.

This is an edited transcript of our conversation, which happened late at night for me, due to the time difference between California and Kenya. Eli had just come back from a run, and he was charged up to have this conversation.

Eli’s background

Rhishi: Hi Eli, thank you for taking the time to chat. I am really excited to talk with you. Can you tell me about your background?

Eli: My background is in engineering. At first, I thought I was going to work on energy hardware, related to climate change, at least as an undergraduate. But I realized I liked not only engineering, but also working closely with people to build things. I ended up at a small company that was called WeatherBill (later called The Climate Corporation). I spent about four years there, and saw the company go through an acquisition.

Monsanto acquired The Climate Corporation for $ 930 million in 2013

It was a fantastic period of learning, and an amazing group of people. Our goal was to help a US farmer increase their production by 3-5%. If you're farming 5,000 or 10,000 acres, and you're producing 250 bushels an acre, a 3-5% increase is enormous.

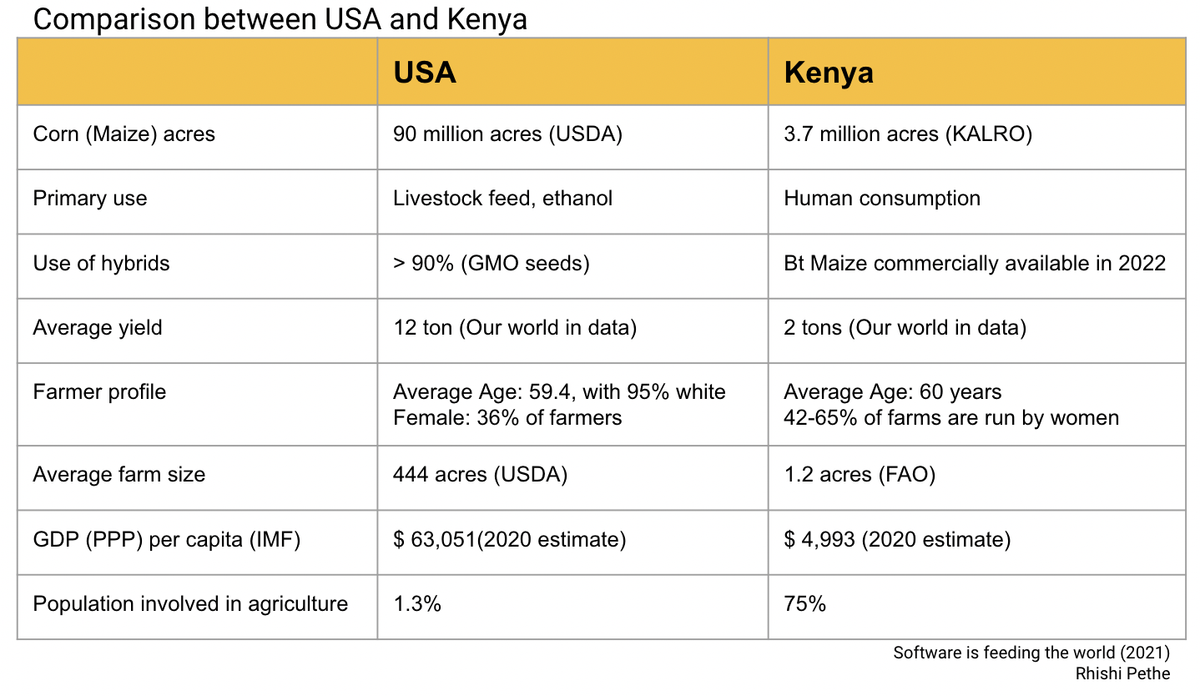

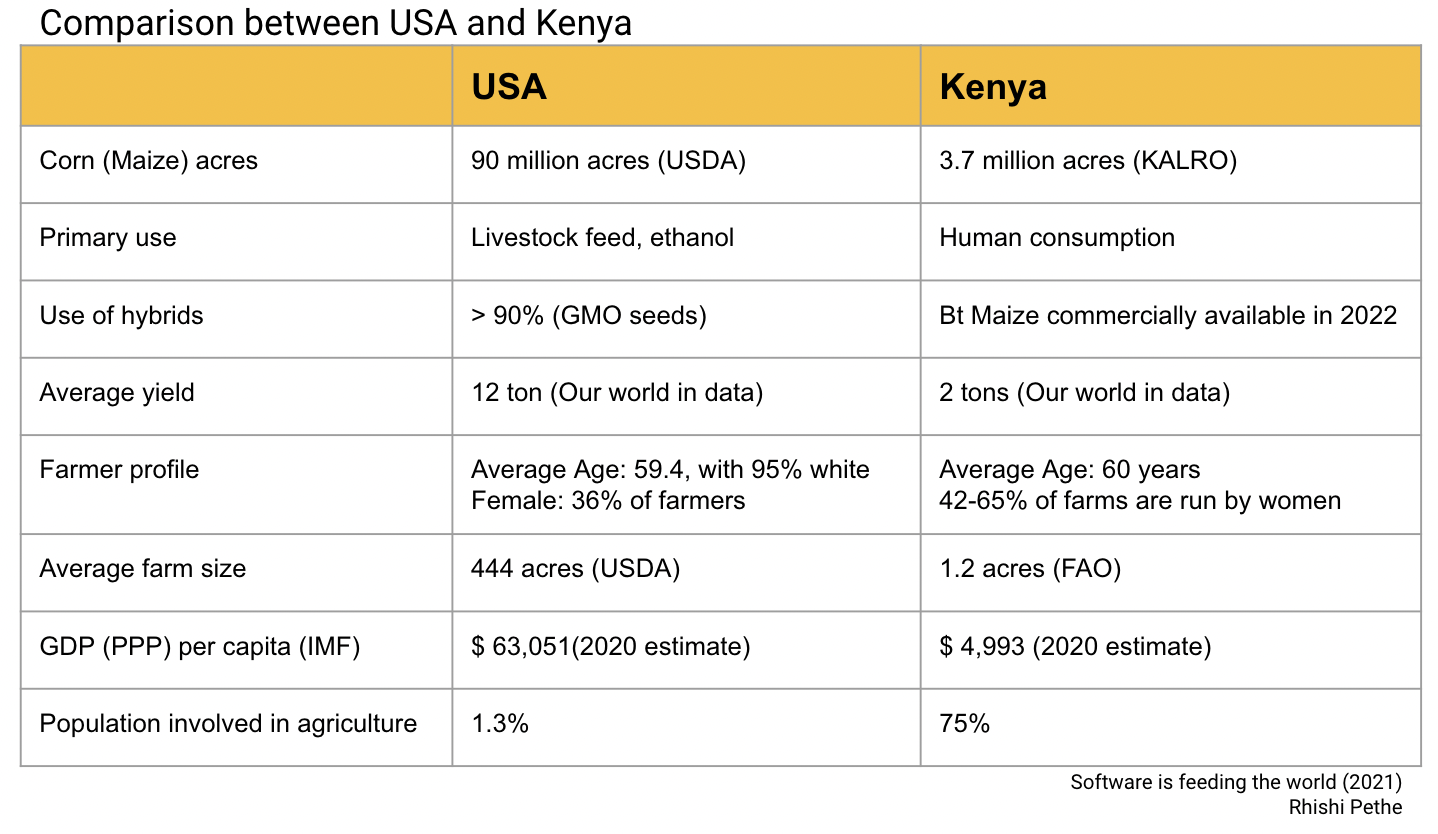

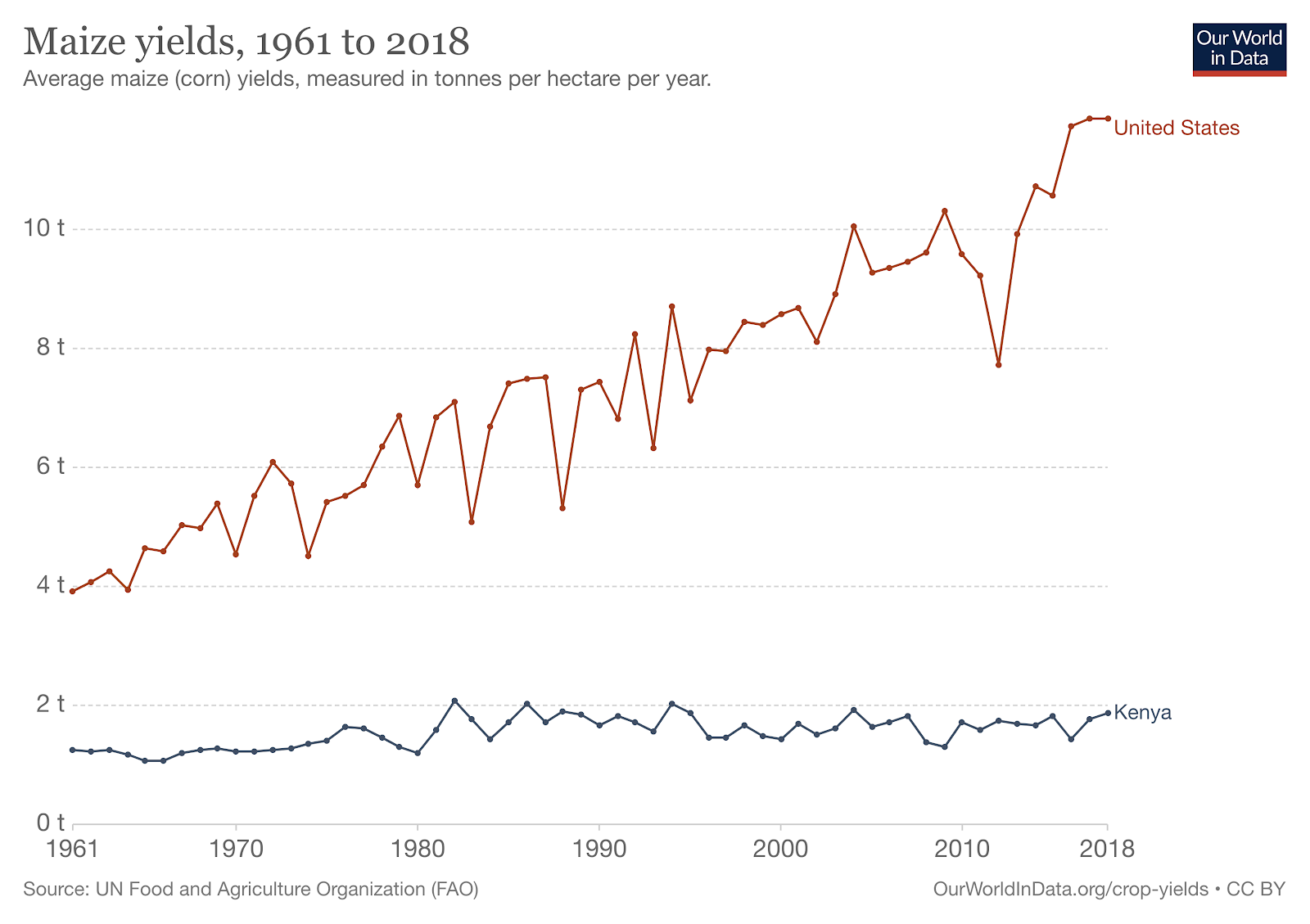

But I think I would just look around and be like, wow, they're planting 20% more acres of corn across Africa compared to the United States and are producing dramatically less. Maybe 10-20% of what US farmers are producing. The Climate Corporation was amazing, but I became fascinated by this even greater opportunity to help farmers double, triple, quadruple their production.

It was exciting both from a financial perspective, and because of the impact we could have on our customers' lives. I was really lucky to team up with a couple of other folks, like ]our CTO Earl (also from The Climate Corporation) and Ben Njenga, who is Kenyan and has been working in ag his whole career. Ben really complemented our Climate Corp experience with an amazingly strong, on the ground, African ag and operations background.

Data sources: USDA (acreage and average field sizes), KALRO, Kenya advances GM Maize, FAO, GDP, Farmer profiles (USA, Kenya)

Challenges with high customer acquisition cost and low lifetime value

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) is the ratio of cost of sales and marketing to the number of new customers. Customer lifetime value (CLTV or LTV) is how much money a customer will bring your brand throughout their entire time as a paying customer.

Rhishi: Wow! That is an amazing story. So, tell me about Apollo Agriculture.

Eli: We founded Apollo to help farmers maximize their profits. At first we focused purely on opportunities to leverage data and machine learning, but as we dug deeper, it became clear that even though there were many learnings from Climate, the business in East Africa was very, very different and would require an entirely new approach.

US agriculture is hyper optimized. It is up there on Maslow’s hierarchy in terms of sophistication. People have all sorts of complaints about the US agriculture system, but rarely would you hear people complain about under optimization. If anything, I think people fear a risk of over-optimization e.g. monoculture etc.

The needs of Apollo’s customers are much more foundational. It's not about the perfect seed, the perfect fertilizer, the perfect irrigation system, the perfect amount of water applied at the perfect moment. It's about good quality hybrid seed, enough fertilizer, and a way to get water into their field.

Our observation was that if we can help a farmer access fundamental tools - high quality hybrid seed, fertilizer, advice and the financing they need to afford it - farmers can see dramatic increases in production, to the order of 2x. The challenge is getting those tools to farmers. Our customer base is incredibly rural, incredibly small scale and incredibly fragmented, and that makes access a critical challenge.

One key challenge is customer acquisition costs. No matter how you cut it, if someone lives 10 kilometers from the nearest center or two kilometers off the tarmac road, it is expensive to acquire that customer and to service that relationship

Lifetime values are also challenging. If you're working with a farmer who farms a couple of acres, you need several thousand acres to achieve the same revenue as one farmer in the US and so commensurately, lifetime values are lower. In a classic business school framing, customer acquisition and servicing costs while using conventional - people and paper - business models have been higher than customer lifetime values.

So you have products and services that can deliver immense value, but the economic model hasn't worked to reach them. And so that's really where we have focused the majority of our attention at Apollo. The products we sell tend to be relatively straightforward from an agricultural perspective: we offer an optimized bundle with farm inputs like seed, fertilizer, and crop protection. It includes advice to support farmers to make good decisions over the course of the season. It includes insurance that protects them in case of a bad year. And then we finance that package,so the farmer can invest upfront and then pay when they've harvested.

We've taken those relatively fundamental agricultural products, but found a way to deliver them in a way that's actually profitable and scalable. We’ve invested in two areas of technology that make that possible. First, it is the right software in the right place to automate our operational processes and drive down acquisition and service costs. Second, we pull in data from a range of sources including farmer behavior and satellite data, link it directly to observations, and build machine learning models to much better assess credit risk.

Disruption theory and pathways to prosperity

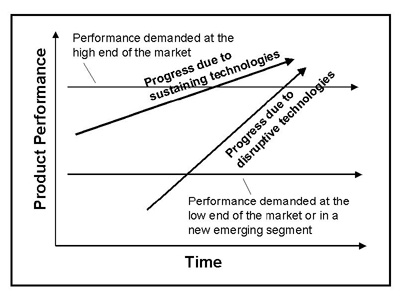

Rhishi: In the US one is trying to optimize an already optimized problem. According to Christensen’s disruption theory, disruptions happen on the lower end of new markets. The market in Africa is a low LTV, high CAC market. Do you think you are creating disruption with your approach?

According to Clayton Christenson “disruptive innovation is the process in which a smaller company, usually with fewer resources, is able to challenge an established business (often called an “incumbent”) by entering at the bottom of the market and continuing to move up-market.”

Eli: I hope so. It's a delicate balance. We're trying to design our product to be minimally disruptive (in a different sense from how you’re using the word), in that we want to offer products that meet our customers where they are, with a very clear value proposition and don’t require them to take a leap of faith on a technology company. For our customers, being a tech company is not really a perk, it’s closer to a bug. In many ways, they’d much rather that we come out and visit them at their farm, rather than serving them through technology.

Customers will accept the fact that we give them a call or we send them an SMS rather than visiting in person because it allows us to offer a product that otherwise isn't available in the market. We want to deliver products that meet our customer's needs today and allow us to deliver fast value and earn customer trust.

There are not only opportunities to come in with these well-understood high return, agricultural products I mentioned, but also opportunities to help reimagine what the trajectory of an agricultural economy looks like. There's a whole set of assumptions around what agricultural development looks like, and I think some of those are right, like hybrid seeds deliver amazing value, fertilizer delivers amazing value. That said, there are also opportunities to do better.

Will the East African agricultural economy end up looking exactly like the US one? Well, I hope not. There's a lot more opportunity for farmers to own value and to invest in sustainability and so on.

We try to figure out how do you strike the right balance between building a product that meets our customers where they are while also providing an aspirational pathway from farming for subsistence to farming as a business.

What we mean by farming as a business is farming as a pathway to a middle-class life, to financial resilience. We talk about hybrid seeds and nitrogen fertilizer and increased maize production, but we think that pathway to farming as a business also means a more diversified portfolio of higher profitability crops, tools like irrigation that can drive down risk and increase profitability, access to better markets over time, access to more land etc. The additional land is not in the order of thousands of acres, but on the order of moving from one acre to five acres.

And so we think that providing the products, services and capital that farmers need to make that transition ultimately has the potential to be immensely disruptive in a technological sense, but, we want it to be minimally disruptive to a farmer’s lifestyle.

Product thinking and customer workflows

Rhishi: As a product manager, I'm very curious about the product bundle. Can you please talk about that a bit more?

Eli: As I said earlier, we want to minimize our product’s disruption to our customers lives. We want our products to align with their workflow, especially their cash flows, so our product bundle includes the key things that a farmer needs to increase the productivity of their land. The bundle includes seed, fertilizer, financing, crop insurance, etc.

The way we deliver the product is also designed to be seamless. For example, we don’t tell customers that to get their bundle, they have to go to an Apollo representative. Instead, they can go to their nearest agri-retail location, and pick up their bag by showing a voucher from Apollo. The whole product and process is optimized to meet farmer’s needs.

Rhishi: I imagine different farmers have different needs. Do you provide opportunities to customize the bundle you offer?

Eli: Yes. We offer a base bundle that is designed to meet a farmer’s core needs and generate a strong return on investment. This means we don’t offer a fully a la carte product. If a farmer comes in and says that they only want to buy seed from us, and nothing else, that probably won’t lead to the significant yield increase we’re targeting (fertilizer is also key) - so it does not work well for us or for the farmer. Due to this we offer a base bundle, which meets the farmer’s fundamental needs, and then we offer different optional add-ons for farmers, on top of the base bundle. These options provide flexibility to farmers.

Pesticides are a great example. Farmers do not necessarily want to make a commitment on the type and quantity of pesticide to buy when they purchase their seed and fertilizer. They often want to wait and see the kind of pest pressure they are getting, and then make a decision based on that. So we offer it as an option. If the farmer decides during the season that they need pesticide, they can go to the local agri-retailer, show their Apollo voucher and pick it up. It is then automatically added to their loan balance.

Rhishi: This is really fascinating. One common theme is that you try to align Apollo to the farmer’s cash flow. Have you looked at milk production and supporting it? The agriculture produce cash flow is choppy, but milk production can create a weekly cash flow and smooth it out. This is a common phenomenon in India.

Eli: Yes, that is a great point. We have recently started looking into it. We expanded product offerings to include livestock care and feed, as most farmers care for livestock. It helps us retain customers.

Rhishi: But do you see milk production as accelerating the pathway from subsistence to middle class, or do you see it as a risk mitigation strategy only by smoothing out the workflow?

Eli: We are looking at different options when we think about the pathway. Can we have them consistently use hybrid seeds, and better quality inputs? Can we get them access to irrigation? The use of hybrid seeds is growing. Hybrid seeds are more drought and pest resistant than local seeds. Can we get them to think about soil health? Can we get them to look at other crops other than maize? Can we get them to a point, where they can expand their farm beyond one acre? These are some of the steps along that pathway, and it is a fantastic framework to think about our impact.

VC and AgTech

Rhishi: Given the time it takes to prove out your product, there is some discussion that the VC model is not the right model to fund AgTech companies. You have worked with Rabo, Leaps, etc. What do you think about the VC model?

Rabobank is a Dutch multinational banking and financial services company headquartered in Utrecht, Netherlands. It is a global leader in food and agriculture financing and sustainability-oriented banking.

Leaps by Bayer is the investment arm for Bayer. “Agriculture today is optimized for the scale of a growing population. Next-generation technologies need to produce better food, better use of land and resources, better nutrition, better sustainability, better solutions for the diverse needs of people and our planet.”

Eli: We have VCs and others that have invested in Apollo. I think the key is that your VCs need to have a very good understanding of your business and the sector. They need to be open to new ideas, and understand the dynamics of the industry. We have been extremely lucky to have experts like PJ Amini, who we both know very well from Leaps by Bayer and others as investors. You cannot underestimate the support and expertise that strong investors can provide. It is really fantastic.

Marginal costs: Do they trend to zero in AgTech?

Rhishi: I want to go back to the question of high customer acquisition costs, and lowlife time value per customer. In classic tech, especially over the internet, you have the notion of economies of scale, and marginal costs going to zero. My friend Venky Ramachandran says that economies of scale do not apply in agriculture, especially in the smallholder space. What is your reaction to that?

Eli: So, when we want to acquire a new customer, we still have sales, marketing, and operational costs. So in the classic Google or Facebook “zero marginal cost” sense, our marginal costs don’t go to zero. But there are definitely economies of scale. When we sign up a bunch of new customers, it helps us learn and improve our operational processes and drive down costs per customer.

For example, when we scale, we buy inputs at higher volumes with discounts we would not get if we were smaller. Or we have better utilization of warehouse space. Or our cost of capital improves. So there are definitely economies of scale at work, but maybe not in the classic internet “zero marginal cost” sense.

Rhishi: You talked about financing, and advisory services. If you look at the work done in Bangladesh with micro-finance, or the work of Esther Duflo and Abhijeet Banerjee, economics Nobel prize winners from last year, financing, and know-how play a big role. Community support is also a big feature in these situations. Do you think about community support around Apollo’s offerings?

In 2019, “Abhijit Banerjee, 58, and Esther Duflo, 46, won the Nobel Prize in Economics, along with economist Michael Kremer, for their "experimental approach to alleviating global poverty.”

Eli: We have not yet invested in building a significant community around Apollo customers, though we love the idea. One challenge here is around building community in a scalable manner before customers have access to smartphones. We are focused on providing the right set of tools and advice to our customers, so that they can manage their risk, and be on the pathway to prosperity that we talked about earlier. We might do something around that in the future, particularly as smartphone adoption increases.

Rhishi: So what are the plans for Apollo? Do you prioritize horizontal growth first i.e. new regions or vertical growth? (new crops, new services etc.)

Eli: We see huge opportunities in both horizontal growth and vertical growth. In terms of horizontal growth, we want to continue growing rapidly to serve customers across Africa. We also want to deepen our relationships with our existing customers, by offering additional value added services on top of our bundle. It can include things like other crops, other products, helping them grow their landholding, etc. At the end of the day, what is really important is that we are helping farmers with our products, and putting them on the right path towards farming as a business.

Rhishi: I read that the use of hybrid seeds is low in Africa compared to other places. Do you see a different uptake in the Apollo customer cohort? You had also talked about sustainability earlier. What is Apollo doing to promote sustainable agriculture?

Eli: This is an area that we’re really excited about.. As an example, sometimes you might meet a farmer who is doing corn-on-corn-on-corn-on-corn. We can help them with the right crop rotation strategy or with more intercropping. We can also help advise farmers on the right hybrid seeds, as the crops from hybrid seeds are often more resilient to environmental conditions. We’re also excited about cover crops and other opportunities to partner with farmers to improve soil health.

Concluding thoughts

Rhishi: What advice do you have for entrepreneurs who want to start to work in a smallholder space in general and in Africa in particular?

Eli: I hope what I say here is useful, although I know that anything I say is entirely a function of my own experience. For readers in the US, the problems that need solving in East Africa are often different from the problems you are used to thinking about. You will need to go deep and really understand your customer very closely. It is likely to be more difficult than you think. You also need to have a really good understanding of what you are good at, and what you are not good at. Build a strong team, ideally with co-founders who complement your weaknesses.

As you build products, think about how to meet the customer where they are. Speed of learning is also critical. In agriculture, you don’t get a lot of chances to iterate on your product in a given amount of time. It is important that you are able to structure your experiments to learn quickly. When you are working with VCs, you probably have funding for 18-24 months. Depending on the region of the world, that probably gives you 2-4 growing seasons during which you can test / iterate.

So you need to have a really clear plan about how you’ll learn quickly, since you have a very short amount of time to do it.

Rhishi: Tell me about your Rainer fellowship from the Mulago foundation.

Mulago is a private foundation designed and built to carry on the life work of Rainer Arnhold. “Mulago finds and funds high-performance organizations that tackle the basic needs of the very poor. We fight poverty. Our job is to find the organizations best able to create change and give them what they need to do it. We fund on the basis of impact and the potential for scale. We do it with unrestricted funds and minimal hassle.”

Eli: The Mulago Foundation is fantastic. They were doing impact work long before impact investing was a thing. The Fellowship was a great experience for me. It is a one year fellowship. You spend one week together as a group of fellows at the beginning and then one week together at the end, and the entire group of fellows is just fantastic.

Rhishi: Is there a movie, documentary, or book you can recommend to my readers to help them get a better understanding of what’s happening in African agriculture?

Eli: Ha ha! Honestly, I don’t watch much TV and don’t read a lot of non-fiction. I mostly read fiction. In this specific area, here is a great non-profit called the One Acre Fund, and a book called “The Last Hunger Season.” It is a great story about the families that work with the One Acre Fund.

Rhishi: Thank you for your time. It was a pleasure.

Eli: Same here!

Conversation Notes

Techcrunch on Apollo’s Series A fundraising

Deepening support for farmers in East Africa: Interview with Eli Pollak on the Accion Venture podcast

How fintech startups can grow by building value for existing users: Case study about Apollo Agriculture

Agricultural productivity in Kenya: barriers and opportunities

Abate, T., Fisher, M., Abdoulaye, T. et al. Characteristics of maize cultivars in Africa: How modern are they and how many do smallholder farmers grow?. Agric & Food Secur 6, 30 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-017-0108-6

Winning in Africa’s Agriculture market, A McKinsey Study, Feb 2019

The One Acre Fund “One Acre Fund is a non-profit social enterprise that supplies financing and training to help smallholders grow their way out of hunger and build lasting pathways to prosperity.”

Mulago foundation “Mulago finds and funds high-performance organizations that tackle the basic needs of the very poor.”

Abhijeet Banerjee, Esther Dublo, Michale Kremer win the 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics