SFTW Convo: Human + AI >> Human only

Tami Craig Schilling gets father-in-laws talking with son-in-laws!

Welcome to another edition of “SFTW Convos” with Tami Craig Schilling, Vice President, Agronomic Digital Innovation Lead for Bayer Crop Science.

Tami’s resume, her list of achievements and community engagement are longer than a CVS receipt.

Tami has spent almost 35 years at Monsanto and Bayer Crop Science! Over more than three decades Tami has had roles in commercial, corporate affairs, R&D, corporate engagement, market development, global agronomic impact, and digital innovation. I doubt there is any role Tami has not been in (maybe outside of facilities???) at Monsanto and Bayer.

Early on in her career, she had the opportunity to work with Dr. Robb Fraley, the father of genetically modified seeds.

Tami is extremely active in her local community. She is on the Board of Trustees for the University of Illinois, on the board of Illinois 4-H Foundation, Illinois Agriculture Leadership Foundation, and has won many awards both for her professional and community involvement. Tami is very active with her family and was recovering from a foot injury sustained while doing a sport activity with her granddaughter!

As you will see through the conversation, Tami is naturally very curious, collaborative, and has a sense of knowing where things are headed. She has recently been a critical part of the team which is responsible for the Generative AI based work done by Bayer Crop Science through E.L.Y.

Summary of the Conversation

In this conversation, Tami Craig Schilling shares her extensive career at Monsanto, detailing her journey from sales to leadership roles in R&D and communications. She discusses the importance of understanding farmer needs, the impact of social media on agriculture, and the challenges and innovations surrounding GMOs. Tami discusses the evolution of agronomic support through data analysis, the introduction of the agronomy wheel, and the impact of GEN.AI on agriculture. She emphasizes the importance of understanding farmer behavior, linking data insights to business outcomes, and preparing the next generation for future agricultural innovations.

Humble beginnings with Monsanto

Rhishi Pethe (RP): Tami, thank you so much for joining. I'm excited to have this conversation. And I'll be honest, when you first sent me details of your experience, I was like, this is crazy. You have spent almost 34 years at Monsanto / Bayer in different roles. This is an impossible task to try to talk with you in an hour. So we'll try to hit some highlights.

Could you give our readers a brief history of your career at Monsanto and Bayer? Which role did you like the most and why?

Tami Craig Schilling (TCS): I grew up in agriculture, but honestly, I didn’t plan on making a career out of it until sometime in high school. That’s when I realized agriculture wasn’t just about raising livestock or growing crops—there were all kinds of jobs beyond what my dad and my grandfather were involved in.

After college at the University of Illinois, I joined Monsanto. And I’ll be honest—my reason for choosing Monsanto probably wasn’t the best way to evaluate a career decision. But at the time, what mattered to me was that Monsanto invested in 4-H and FFA. I cared deeply about those ag youth organizations and their role in communities, both small and large. That shared value—believing in the importance of youth and community—sealed the deal for me.

I started in sales and spent the first 15 years of my career in sales management and customer operations. My first role was as a crop protection sales rep in Michigan. Over time, I moved into sales management, leading teams in Illinois and Missouri. I saw firsthand how Monsanto transitioned from a small crop protection company into a major player in seeds.

Tami Craig Schilling (Image provided by Tami Craig Schilling. Artist rendering by EI)

My background was in Ag Communications, and that opened up an opportunity to shift into corporate affairs. I worked on media, issues management, product launches, and eventually strategy operations, where I led training. This was around the time social media really started taking off, and I led a global effort to educate our employees on how to talk about who we were as a company and what we stood for. There were a lot of misunderstandings—people didn’t know what we were trying to do, and, frankly, the company didn’t always realize how important it was to show up and own its role. That was a huge responsibility. Through that effort, I personally trained around 6,000 employees worldwide, and I learned a ton in the process.

Then Dr. Rob Fraley, our head of R&D, reached out and said, “Hey, I want you to lead R&D pipeline communications, sit on our leadership team, help us make pipeline decisions, work with the board of directors, and get our technology leaders out there—talking with farmers, employees, and the scientific community.” So I did that for a while, then transitioned into global community engagement, focusing on our social licences to operate, then moved into business sustainability strategy integrating sustainable practices into our operations.

At that point, the company was preparing for an acquisition, and I felt pulled back toward the commercial side of the business. After 15 years in commercial, 11 years in other functions, I returned to help shape communication strategies for growers, partners, and employees. I leaned on everything I had learned—about our pipeline, the challenges we faced, and the importance of bridging those gaps in understanding.

Whether it was applying products or using biotech traits, I wanted to bring that understanding to farmers. Around that time, I was sitting in a two-day meeting about customer experience, looking at company metrics, and something just clicked. I immediately latched onto the idea of improving how we handle product and agronomy components to enhance the farmer’s experience with us as a company—while also improving the experience for employees and partners along the way.

That led me to spend the last eight years in an organization we call Market Development, which sits between R&D and sales and marketing..

During my time in North America, I spent a lot of time studying how people make decisions—how they move, what influences them. One of the things that’s always fascinated me, going all the way back to when I was a little girl reading farm magazines on my grandparents' floor, is how farmers get their information. What sources do they trust? How do they make decisions? And as an industry, how do we do the best job of giving them the information they actually need—not just company talking points, but the real, useful insights that help them tackle their challenges?

By 2018, it became clear that things were shifting. We saw that 40% of farmers were checking Facebook at least once a day. If 40% of your market is in one place, you have to be there. You’re doing yourself a disservice if you’re not. So we launched a massive initiative to get our 100+ agronomists on social media—not just to be present, but to actively share important insights in a way we’d never done before.

The knowledge transfer team did some really innovative things in the digital space. It didn’t replace the traditional way our people called on farmers—it just put more information into more hands. And as we started creating videos, we realized we weren’t just reaching farmers in the U.S. and Canada—we were reaching a global audience. That’s how I ended up in a global role, doing something very similar on a much larger scale.

At that point, we were trying to solve a big question: How do we take all this valuable knowledge and get it into the hands of employees, partners, and farmers? There was a massive amount of information, but knitting it together wasn’t simple. Farmers make decisions based on so many factors—their behaviors, crop management practices, field characteristics, soil conditions, the environment, and then agronomy challenges like weeds, diseases, and insects that change constantly. On top of that, they’re dealing with products not just from us, but from multiple companies.

So we started exploring different ways to connect all of this information in a way that actually improved the farmer’s experience over a full 12-month cycle. It wasn’t just about treating farmers as a single group—it was about understanding what each farmer needed, when they needed it. The horticulture grower in California has completely different concerns than the irrigated farmer in Nebraska or the corn and soybean grower in Illinois. And that challenge? That became a huge passion of mine.

We didn’t get the full funding for the project in 2023, and by 2024, it was clear that wasn’t going to change. But then ChatGPT came out, and several of us started having the same thought—if we can’t build the infrastructure ourselves through IT systems, can we leverage what’s already here?

For the last year and a half, I’ve been fully focused on how to use generative AI and large language models to build a farmer-focused product and agronomy tool that’s better than anything off the shelf. Something fine-tuned, highly advanced, ahead of everything else out there.

A lot of people are interested, but at the end of the day, the decisions farmers make—and the information we provide—have to be right. That’s what I’ve been working on, and we’ve launched a tool within our company that’s been absolutely game-changing.

Monsanto culture and a learning mindset

RP: What has kept you at Monsanto / Bayer for a long time?

TCS: At Monsanto and Bayer, innovation isn’t just a buzzword—it’s a way of life. It’s what we do. We’re constantly looking at what’s new, what’s next, and more importantly, what it means for farmers. How does this technology impact them? What does it mean for our company? Are there new business opportunities? What should we start, stop, or do more of?

That environment, that culture of always pushing forward, is why I’ve stayed. When I first took the job, I figured it would be five years and I’d move on. But here I am, over 35 years and 12 different roles later—growing, learning, achieving. I got to sell as a sales rep. I got to sell some of the very first Roundup Ready soybeans on the market. Back when Asgrow, owned by Upjohn at the time—not Monsanto—was growing them in Michigan, that was my sales territory.

And when you see it in the field—the difference between a weed-free crop and the one right next to it where the farmer is struggling, losing yield, losing income, even after spending so much on weed control—that stays with you. I’m a farm girl at heart, and the first time I saw a Roundup Ready field, it was spiritual. People might laugh at that, but I don’t care. It was real for me. I saw something that could change how crops were grown…and it did.

Of course, we know Mother Nature doesn’t just roll over. She evolves, she adapts, she fights back—that’s how it works. But what I’ve loved is being part of a company that refuses to give up that fight. The fight to help farmers protect their crops, protect their yields, and not just survive—but thrive. And when farmers thrive, small communities thrive. There’s prosperity. Young people can stay, build futures, or go out into the world and chase new opportunities.

That’s the big picture. That’s why this work matters.

RP: I didn't see that field side by side. I've seen pictures, but the difference is so stark between the two management practices that you have to explore to see what's happening there.

Something I picked up in your answer. You want to look at what is new, interesting, and valuable. You don't do it just for the sake of this shiny new object to play with. It's something new and it's impactful for the things that you care about. You have a spidey sense to pick up trends and understand its implications.

But let's start with your work with Dr. Fraley. It was a big trend of GMOs with amazing new technology, which have gotten a lot of bad press over the years. What was it like to work with Dr. Fraley? What was the reaction from growers? You worked in communications and you were right in the middle of it.

TCS: When Dr. Fraley offered me the opportunity to lead communications for our R&D organization, we were right in the middle of launching new technologies—new GMOs. I was involved in several major launches: insect-protected corn, cotton, soybeans. Then came the relaunches, the second-generation versions, the third-generation improvements. Having sold these products, then worked on media and events around them, stepping into the R&D pipeline felt like coming full circle.

There were about a dozen of us on the technology leadership team—PhDs, industry veterans, experts in regulatory affairs, chemistry, biotech, and breeding. And then there was me—a farm girl from Southern Illinois, deeply passionate about farmers and production. And on top of that, I’m a farmer’s wife. There were plenty of moments where I could have felt like the odd one out in that room. But I never did. That was part of the culture—everyone’s voice mattered. If you had a perspective, you were expected to bring it to the table.

And because I had real-world experience with these products in the field—and stayed close to what was happening on farms, whether in India, Brazil, or Indiana—I was regularly asked for my take. It wasn’t just an R&D team; it was an R&D team grounded in real farmer perspectives. That connection was built into everything we did.

RP: So let's go to the GMO experience. As a communications professional, what did you learn from it?

TCS: At the time we were looking at the next big problems farmers were facing and two challenges stood out: weed control and insects.

I look at everything we’ve launched over the years, and it’s incredible how many problems we’ve checked off the list. Some of the things that used to be massive issues just aren’t anymore. Take the bollworm. Before Bollgard cotton, the bollworm devastated the entire southern U.S. cotton belt—not just farmers, but whole communities. Bollgard cotton wasn’t perfect, but it was a game-changer. It created a stopgap that helped control the pest and had environmental benefits.

That’s actually one of the reasons I was so passionate about the training program I led. I wanted our employees to tell the real stories. Think about what it means when a farmer no longer has to spray insecticides multiple times. Cleaner fields. Cleaner water. GMOs, which are among the most highly regulated and studied technologies out there—and managed in a highly ethical way, because I’ve been in the labs, I’ve seen the work—brought solutions that had ripple effects beyond just farming.

Take something as simple as eagles. We didn’t have eagles flying around our farm 15 or 20 years ago. Today, we have a big nest just a couple of miles through the woods, and we see them all the time. Why? Because when you remove certain manmade chemicals, the environment shifts. We never claimed GMOs would bring eagles back—but we had a hypothesis that if we reduced insecticide use, the ecosystem would respond. And it did. That’s the kind of unintended consequence that’s phenomenal. And for me, it’s personal. My husband was the one handling those insecticides in our farm shop. And now he doesn’t have to. Instead, he uses Dekalb insect-protected hybrids.

I remember sitting with Dr. Fraley and some folks from USDA Rural Development at a very muddy Farm Progress Show. There were maybe four of us at the table, and the question was simple but huge:

"Can you predict what corn yields will look like in 2030? Will we have enough for livestock and ethanol?"

Most people don’t realize food is just a small part of what #2 yellow corn is used for. Livestock and fuel production take up a massive share. So Dr. Fraley and I went back with a team of statisticians and experts and started modeling. Not long after, we announced our prediction: by 2030, corn yields could reach 300 bushels per acre. At the time, the average yield was around 177 bushels per acre.

I’ll never forget that moment—sitting in Iowa, having that conversation. And there are hundreds of moments like that in my career, where I got to be there, watching these decisions unfold in real time.

I was on the R&D leadership team when we reviewed a promising GMO crop trait, but it had the potential to trigger an allergy. The science team brought their findings forward, and we had one conversation: we don’t support the use of anything that could be an allergen in food production. It was too risky. So we shut it down. We stopped funding it—just like that.

That’s the part I wish more people could see. These decisions aren’t made lightly. They’re not made based on what’s best for the company. They’re made based on science and what’s right for people. Because any company that only thinks about itself? It won’t last.

Dealing with unintended consequences

RP: When you talk about unintended consequences, they can go either way - good or bad. That is why they are called unintended consequences. What did you, your team and the company do to minimize or at least start to understand what could be some of the negative unintended consequences? I am sure it was difficult. But I would love to see what was the thought process there and how did that get into your decision making process?

TCS: Oh, absolutely. It was a huge part of it. The R&D team kicked off the process by diving into a ton of numbers. What’s the acreage for different crops across various geographies? What pest challenges are out there? What environmental factors need to be considered?

And I’m not kidding—thousands of us, all over the world, spent our time thinking about what could go right, what could go wrong, and constantly working to minimize the risks. And I mean constantly. The beauty of it is that many testing protocols are already built into the regulatory system.

But not everything, right? That’s why we always looked for the smartest people—specialists in their fields—and connected them with farmers. Because here’s the thing: scientists and farmers don’t always see the full picture on their own. But when you bring them together to talk about a new technology, concept, or challenge, the perspectives that emerge? Incredibly powerful.

That’s one of the things I always valued about the company—how much work went into this. Dr. Fraley and other R&D leaders would spend time with the American Soybean Association, the United Soybean Board, the National Corn Growers, and the Cotton Council. And it wasn’t just ag—we showed up at plant and animal genomics conferences, non-ag science forums like AAAS, you name it. The goal was always the same: bring the best minds together. Whether we were hosting those discussions or showing up where the conversations were already happening, we wanted the smartest thinking in the room.

A lot of companies in ag tech had roots in pharmaceuticals, which meant they already had that “do no harm” mindset. And when it comes to food, that’s non-negotiable. The industry spends millions—probably closer to billions—on testing. I’ve walked the test fields, been inside the labs, seen the third-party agreements. It’s rigorous. And if you’d ever sat in one of our regulatory meetings, you’d know—those folks weren’t there to nod along. Their job was to poke holes in everything. “What if this happens?” “What about that?” “Have we considered this?” Nobody just sat around saying, “This is great.” It was constant questioning, constant scrutiny.

And that’s exactly why an R&D pipeline took eight years to bring a product to market. Now, it’s more like ten or longer. And you know what? I don’t think that’s a bad thing. Sure, you need balance in regulations, but scientific rigor? That’s non-negotiable. We’re talking about food. People’s health. You don’t take shortcuts. But at the same time, we also need to figure out how to feed the world in the most sustainable way possible.

Honestly, my time in R&D changed me. Completely. It made me a more data-driven thinker, way more analytical. It reshaped how I see the world. And Dr. Fraley? Best boss I’ve ever had.

(Re) Inventing the Agronomy Wheel

RP: Anybody who got a chance to work with Dr. Faley, I mean, that's a blessing in itself. You talked about how you spend a lot of time understanding what are all the decisions that a farmer makes and what is the right way to engage with them and when with information and knowledge.

I remember when I was at the Climate Corp, there was a 50 or 100 foot long chart with all the things a farmer does throughout the year. How do you use that to understand what decisions they make? What do they consider? You and your team came up with interesting ways in which to communicate that and educate the teams to know when to talk about what. Could you talk about that experience and some of the artifacts that you came up with, which are new at that point of time.

TCS: Social media, digital communications—even texting—completely changed how we deliver information to farmers. The old way was straightforward: you did media stories that farm radio and publications picked up, and you held farmer meetings. That was it.

It’s crazy to think about now because digital tools feel like such a big part of life. I can’t even imagine not having those options. But back then, even with websites, we were still guessing what farmers needed based on farm visits, market research, and direct conversations. I used to sit in farmer meetings and ask, What’s on your mind? What are you thinking about right now? That was how we figured it out.

Fast forward to the digital age. We started hearing a recurring theme from growers in focus groups and market research:

"I need information when I need it. Brought to me."

That changed everything. I was leading knowledge transfer at the time, working with a fantastic team of innovators—some from ag, some from outside the industry, which made for a great mix. And we asked ourselves:

"What if we could deliver the right information, in the right form, at the right time, in the right place?"

Form mattered—a lot. That’s when we started leveraging social media. But then came the next big question: What’s the right information?

I live on a farm in Southern Illinois. The right information for my husband isn’t the same as the right information for a grower in Texas who’s already planting corn. Farmers aren’t a homogeneous group. So how do we figure out what they’re thinking about at different times?

That’s when we turned to data.

Our websites had backend analytics that told us exactly what questions farmers were searching for and what articles they were clicking on. We had hundreds of agronomy articles—covering everything from soil fertility to conservation tillage to pest management. And then we thought: Can we figure out where these farmers are located?

We didn’t know individual farmers, but through IP addresses, we could see their general geography. And when we started digging into years of data, we realized we had millions of data points to work with.

What we found was fascinating.

Some of our long-held assumptions were wrong. A few of us who grew up on farms assumed farmers were focused on certain topics at specific times of the year. But the data told a different story.

So, we pressure-tested it. I’d come home and bring it up with my husband. "Does this timing make sense to you?" And sure enough, he’d say, "Absolutely. I focus on fertility in December and January, not in March when I’m applying it." If we had been farming in Central Illinois, where it’s cold enough to apply anhydrous early, that focus would have shifted to September—exactly what the data showed.

We realized that it’s not about the calendar month—it’s about the crop cycle.

Wherever you are in the world, farmers are either planning, planting, growing, or harvesting. They plan throughout the process, but there’s a huge surge in planning right after harvest to right before the planter starts rolling.

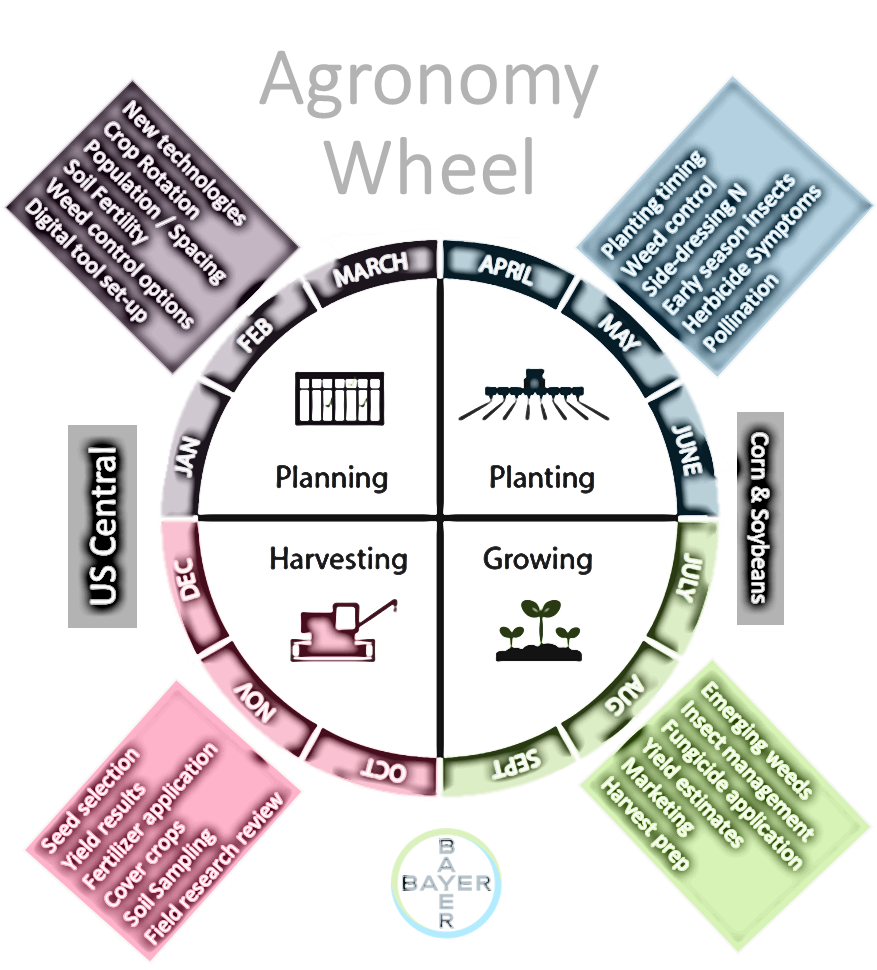

That insight completely reshaped how we supported farmers. We coined it the Agronomy Wheel, and what’s amazing is that it applies to any crop, anywhere in the world.

Agronomy Wheel (Image provided by Tami Craig Schilling)

Take blueberries, for example. If you’re growing blueberries in California or Michigan, you’re not planting a whole new field every year. But you’re still cycling out older plants, introducing younger bushes, and managing that growth cycle. The rest of the wheel—fertility, pest control, harvesting—still applies.

And here’s the thing: we’ll never be finished. Farmers’ needs evolve. New technologies emerge. But what we started doing was mapping out content to proactively provide the right information at the right time.

If a farmer opted in, we’d send automated emails tailored to their needs. Some wanted just three bullet points. Others wanted full paragraphs, deep research, and sources. So we adjusted our writing style to match those preferences. And the results? Engagement skyrocketed.

We also synced our social media strategy with this data-driven calendar. Every Friday, one of our team members, Nick—who was both brilliant and hilarious—sent out an internal newsletter to our field team. It laid out the top three agronomic topics for each region for the upcoming week.

This also strengthened our relationship with marketing. If we knew a weather event was coming, we’d proactively publish an article and get it into people’s hands before they needed it.

And the beauty of using modern tools—Adobe, Marketo, and others—was real-time feedback.

One of the most surprising insights? Farmers read their emails most consistently on Thursdays at 6 a.m..

We tested different times, and Thursday morning always won. As a farmer’s wife, I thought about it, and it totally made sense. But the most exciting part? We didn’t have to guess anymore.

Instead of asking farmers what they wanted, we let their behaviors tell us. And that changed everything.

RP: You were able to start with a hypothesis and then look at the data to see how to personalize the experience to that particular farmer, depending on their context. They might be growing blueberries or corn, and they might be in different parts of the world. I mean, you reinvented the wheel here in a different way!

And impressions is one thing, which is a good metric to see how this is going. But were you able to link that to any of the business outcomes? Is this cohort of farmers sticking longer with our brand, or are they buying more from us. What are some of the business outcomes you were looking for?

TCS: What’s funny about agriculture is that it’s both a high-tech industry and a deeply human-centered industry—at the same time. And I love that intersection.

What we found was that information, timing, and delivery alone don’t make the sale. But when we provided the right information, in the right format, at the right time, it strengthened relationships and built trust.

We didn’t just send information to our sales reps—we made sure our partners were getting it too. These partners included seed licensee companies selling different brands that we supported and provided genetics for. Our goal was for the whole industry to benefit from this. We didn’t keep it locked inside—we shared it. Even large retail organizations adopted the Agronomy Wheel concept after seeing its impact.

And the results were powerful.

We saw multiple examples of stronger relationships forming just because farmers felt heard. They saw that we weren’t just throwing out information—we were responding to their actual needs, just in time.

One of my favorite stories is from an agronomist who had a farmer (and his father-in-law) come to him and say something that really stuck with me.

This agronomist, who was featured in the local Bayer Agronomy Update, had been talking with his father-in-law, when the father-in-law brought up an article he had read. He told him, "I was surprised to learn that such-and-such problem can be solved by this approach and more surprised when I saw it came from you."

Now, here’s the thing—this father-in-law had never talked with his son-in-law about agronomy like that before. But because we had sent out personalized, localized information—specific to the Southern Corn Belt, not just some generic message—it sparked a conversation that never would have happened otherwise.

And that’s what made this initiative so effective—it worked on two levels.

What we saw was that this approach made a real difference in two big ways.

First, it helped our people show up in more places and conversations. Getting our agronomists active on social media meant they weren’t just showing up at meetings—they were present where farmers were already looking for information. The Agronomy Wheel gave them the right insights at the right time, so they could provide value when it mattered most. And over time, their local reputation grew, not just as sales reps, but as trusted experts in their communities.

Second, it showed farmers and retail partners that we were doing more than just pushing products. We weren’t just sending out sales pitches—we were providing real, useful agronomic insights on fertility, soil health, pest control, and crop management. Many of the people delivering this information weren’t marketers—they were retired agronomists and technical experts who understood the science behind it. These weren’t sell sheets. They were technical bulletins designed to help farmers solve real problems in the field.

That’s what made the difference. Farmers didn’t just see us as another company trying to sell something. They saw us as a resource they could trust. And farmers appreciated that.

They told us, "There's a time for marketing, but there's also a time when I need to know how to do this right—technically."

There was a trust component built into this effort. When we provided timely, useful information, it reinforced to farmers that we were looking out for their best interests—which, in turn, was in our best interest.

And here’s the best proof that it worked:

We saw, through research, that some of the problems farmers used to have—like not getting the right information when they needed it—were disappearing from their list of concerns.

Because we had become more responsive.

And that? That changed everything.

Working with Generative AI

RP: How is this role different from previous roles? How do you think this gives you a new or a different way to engage with and communicate about what you're doing or what should be happening? And how is this mechanism of engagement, not just different from a technical standpoint, but what does it do differently and how does it do differently compared to social media and email?

TCS: What’s been fascinating about this role is how much it has shifted my perspective. For most of my career, up until the last few years, I would have been considered a generalist.

I knew our product lines. I knew farmers and how to reach them. I understood the role agriculture plays in communities and the industry as a whole. I worked across many different areas, but I wasn’t deeply specialized in any single one. That changed in the last few years. In this role, I’ve felt more like a specialist—but in two very different spaces.

First, I’ve become a specialist in a brand-new technology.

We were the first Bayer Crop Science team to move forward with a generative AI project. In fact, we won the Outstanding Trendsetter Award from Global IT—not just Crop Science, but Global IT. That’s pretty wild, right? We weren’t just early adopters. We were ahead.

I was recently on a panel with some incredibly credentialed executives—one of whom has 100,000 LinkedIn followers. They were brilliant, no doubt about it. But none of them had actually been in the trenches, building a generative AI tool.

That’s why I was there. Because I’m not just talking about AI—I’m part of the team figuring out how to actually make it work. How do we build question-and-answer templating? Which LLM should we be using as our foundation? How do we structure a tool that works in real-world ag scenarios?

Two years ago, I wouldn’t have imagined myself in these conversations. But now, here I am—constantly learning, pushing myself to keep up, and contributing in ways I never expected. It’s a huge leap, but I love it.

At the same time, I’ve also become a specialist in something I’ve known my entire life—agronomic and industry knowledge.

In our core team, I’m the one who brings the farming perspective. I’ve worked with teams across multiple countries, mapping out how different regions approach crop production, understanding financial, tax, and regulatory challenges, breaking down the unique dynamics of farming systems like the Safrinha crop in Brazil, and identifying how farmers plan and make decisions throughout the season.

I’ve sat in rooms with giant white sheets of paper, marker in hand, mapping it all out—making sense of it all.

At this stage in my career, it’s been incredibly fulfilling to wear the specialist hat—but in two completely different ways. In one, I’m learning and building something entirely new. On the other hand, I’m applying decades of knowledge and experience. And somehow, they’ve come together in a way I never could have predicted.

I grew up in a world where your sources of information were pretty limited. You had three TV stations, a local newspaper, and maybe a couple of radio stations—if you were lucky enough to pick them up. That was it.

That’s not the world we live in today. Some people call it splintered media, some call it bifurcated media—whatever you want to name it, the reality is that there are more ways to communicate than ever before.

This hit me last fall at a basketball game. I was in one of the tractor company’s suites, catching up with some friends, when I got into a conversation with a farmer about what I do. By the end of it, we had set up a meeting for Commodity Classic to preview our E.L.Y. Agronomic Intelligence tool. Even though we haven’t officially released it to farmers yet, we want to start sharing it—not as a replacement for anything, but as an augmenter.

E.L.Y. isn’t here to replace websites, social media, or traditional information sources. Farmers aren’t going to stop watching short-form videos while they’re waiting in line at the grain elevator. That’s just part of life now.

But E.L.Y. solves a different problem—one that farmers have been telling us about for years:

"There’s too much information. I just need what I need—when I need it."

That’s exactly how we built E.L.Y.

Take a simple but critical agronomic question: "Can I spray this product?"

Instead of making you dig through a 30-page label, E.L.Y. delivers the answer fast. It tells you whether the product is labeled for your state, gives you the necessary context before applying, and provides a direct link to the official product label.

But what makes E.L.Y. different is that it doesn’t just stop at answering that one question—it anticipates the next logical step.

If you ask, "Can I spray this?", the natural follow-up might be, "What else do I need to know?"

E.L.Y. understands how decisions are made. Instead of leaving you to piece things together yourself, it guides you through the process, ensuring you have the right information at the right time—always backed by real, sourced data.

Some people worry that AI will take their jobs. But one of our sales reps put it perfectly:

"I’m not worried that AI will take my job. I’m worried that a competitor with AI will take my job if I don’t adopt this technology."

That’s the real shift. AI isn’t replacing people—it’s giving them an edge.

Think about how much time gets wasted today. Searching through Google results, sifting through outdated or irrelevant information, pulling up a laptop and scrolling through PDFs just to find one answer. Now imagine cutting that process down to minutes—or even seconds.

That’s what we’re building.

E.L.Y. isn’t here to replace agronomists or sales reps. It’s here to give them back their time—time to make one more call, visit one more farm, actually be present instead of being stuck in research mode.

We’re not in the days of carrying around big boxes of brochures anymore. This is a new world. And our job?

To bring it forward in a way that works for farmers, agronomists, and the industry.

What and how should we learn?

RP: You mentioned how critical domain knowledge and agronomy expertise are in this space. Without that foundation, it would be nearly impossible to build a strong version of something like E.L.Y. That’s one key factor.

The second point that really stood out is your take on augmentation—how AI isn’t replacing people, but enhancing their capabilities. As you said, someone with AI will outperform someone without it. That seems to be the headline from the salesperson’s perspective.

But at its core, it’s still about personalization—delivering the right information, at the right time, in a way that’s quick and relevant. AI also makes agronomists and salespeople more efficient, allowing them to focus on strengthening relationships and spending more time with customers.

You also touched on the concern about AI taking jobs. That leads me to a broader question—one I think about a lot.

You serve on the Board of Trustees for the University of Illinois, and I imagine this is something you’ve thought about as well. I have a teenage daughter and an 11-year-old, and I often wonder: What should we be teaching them?

With AI increasingly automating research and decision-making, what are the most valuable skills for students today—whether they’re in high school or college?

Given your role at the university and your experience working directly with cutting-edge technology, how do you think about preparing the next generation for the future? What skill sets will be most valuable in a world where AI is doing more and more of the heavy lifting?

TCS: This is a topic I think about a lot because of my responsibilities, but also because I’m deeply involved in the National FFA Sponsors Board. I represent Bayer there, and we spend a lot of time thinking about how to prepare the next generation to work in agriculture.

The first part of that is exactly what you mentioned—these tools are not just intriguing or fun, though they certainly can be. The real value is in how you use them. As young people move into the next stages of their careers, the question isn’t just about knowing these tools exist, but about figuring out how to put them to work in a meaningful way. No matter what field they go into—whether it’s agriculture, business, or even a nonprofit where they’re advocating for a cause—they’re still serving someone. The key is learning how to bring together all the tools at their disposal to do something innovative and new.

That’s how we approached social media in agriculture. Our kids grew up with Facebook, right? But we took that same platform and made it work for farmers because that’s where they were. Now, if you go on Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat—you’ll see agriculture is alive and well in those spaces. My son is in the cattle business alongside the farm, and my husband joined Facebook just because that’s where cattle were being marketed. Now, Snapchat videos are being used for the same purpose. And who knows what tools will come next? That’s what makes this all so exciting—we’re constantly adapting.

The second piece, and this is the one I think is even more important, is critical thinking.

I use GenAI to clean up sentences, make something clearer, or tighten up language—but I still read the sentences. I don’t assume they’re always right, because they’re not. We call it intelligence, but I’m not sure I’d go that far. It’s a tool, and like any tool, it’s only as good as the person using it. There’s no replacing human context and critical thinking.

That’s why I don’t believe AI or technology is going to homogenize everything or make everything the same. The human mind is still in the equation. It’s what asks the questions, challenges assumptions, and decides what’s worth keeping. That’s the biggest piece for me—don’t just accept what’s in front of you. Step back, ask the questions, read the content.

If you’re using AI to help write a paper, read the damn paper. That’s the least you can do. You don’t have to go pull out an encyclopedia like we did growing up—it’s faster, easier now. But instead of just taking the shortcut, maybe use that saved time to actually think about your position, develop your ideas, and sharpen your argument.

This shift is going to unlock a lot of potential. It’ll make mundane tasks simpler, but at the same time, it’s going to put more pressure on people to think critically. And honestly, I think that’s a good thing.

Future Casting

RP: You’ve seen several major technological evolutions—GMO technology transformed agriculture, social media changed how we communicate and personalize interactions, and now we’re seeing the rise of generative AI, which can personalize experiences, automate tasks, and provide instant access to the right information.

Looking ahead, with advancements in automation, robotics, and AI, how do you think farming and agriculture will evolve over the next 10 years?

Let’s say we’re in 2030 or 2035—pick your year. How do you think agriculture will look different compared to today?

I know predictions are tricky, and most don’t play out exactly as expected, but in broad strokes, what are the key shifts you anticipate?

TCS: If I could paint a picture of what I want the future to look like, I know exactly what I’d change.

Right now, if I opened my husband’s desk, I’d see stacks of paper. We’re still a very paper-driven industry. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it just is. And the real issue is that our data systems still aren’t connected to the farm.

I see what it takes to keep things running. When Bayer sells products to a retailer, and that retailer sells products to my husband, there are two separate billings—and that’s fine, that’s necessary. But there’s no real communication between those systems. We’ve made progress, but we could still go miles further. I see how much time gets wasted just sorting through invoices, making sure prepay money got applied to the right place, and tracking everything down.

That’s non-productive time. And it’s frustrating, because so many startups have tried to solve this, but we still don’t have an end-to-end system that truly works for growers. The tools built for retailers aren’t the same as what farmers need. And until we figure that out, we’re never going to solve the problem completely.

I see an opportunity here, but the solution has to go deeper. It’s not enough to just have good farm management software. It has to be connected—to farm practices, to geospatial mapping, to the crop cycle, to tax cycles. It has to function the way a farmer actually thinks and operates. In my head, I think of it like a Nest system for the farm—something that seamlessly integrates all these moving parts without being cost prohibitive for growers.

I think that’s one of the biggest reasons why technology hasn’t been fully adopted in this space. Too many solutions have only tackled one piece of the problem, and for the cost, it just wasn’t worth it because it didn’t connect everything else.

My son is 24, has a degree in markets and management, and is home farming. He’s used to connected tools. He expects things to work together. But in farming, we still don’t have that—not at the level we should. We don’t have good connected tools that help farmers truly monitor and manage their operations in a way that feels seamless.

That said, I still believe there’s no substitute for being out in the field. Whether it’s the farmer, their employees, or their agronomists, there’s still a human connection to farming that can’t be replaced. I don’t think we’re moving to a world where everything becomes fully autonomous, but I do think farmers are going to start looking at some of these options more seriously.

One of the areas I’m most excited about is pest monitoring. There’s a lot of potential in this space, and I think it’s going to change the way people farm. Just like I get a weather alert on my phone, farmers will get alerts when conditions are right for a certain pest outbreak. Or a sensor in a specific field will notify them when a particular insect has reached a threshold that might require action.

That’s game-changing. Because scouting for pests is hard—it’s time-consuming, and it’s tough for farmers, agronomists, and retailers to do effectively at scale. If we can develop better scouting tools, I think we’re going to see some really cool innovations in the industry.

And that’s what excites me. The possibilities aren’t just theoretical—we’re already seeing pieces of this come to life. The challenge now is bringing it all together in a way that actually works for farmers.

Relevant SFTW editions

- “POC to OMG! The Realities of Deploying GenAI at the Farm Gate” White Paper on Generative AI with case studies (February 2025)

- SFTW Convo: Meeting Farmers Evolving Expectations (February 2025)