Steve Sprieser: An old model to fund AgTech Innovation

What are the alternatives to the VC funding model?

Steve Sprieser is opinionated. Steve is a nerd for financial models to fund innovation.

He is a first principles thinker, who sometimes comes across as a contrarian thinker. Steve is currently the Founder of Cerulean Venture Partners, where he advises investment funds and early-stage startups in the healthcare, agriculture, and life sciences sectors.

Prior to being an investor, Steve was the co-founder and CEO of Petrichor, which provides technology solutions for supply chain management for ingredients and commodities. Steve has experience working in healthcare, and biotech as well, and so he brings an outside in and inside out perspective to the AgTech space.

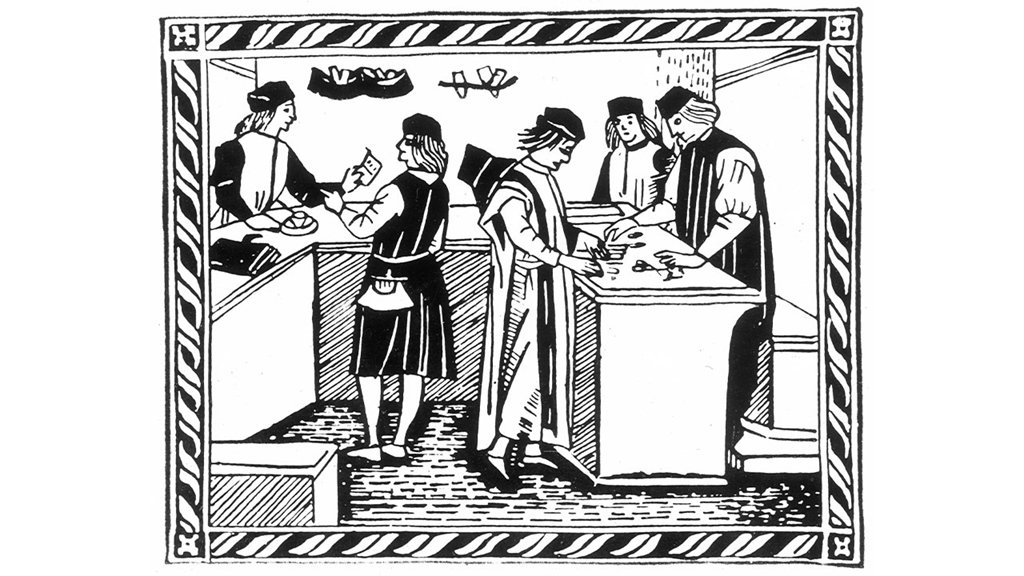

Steve has been researching and working on exploring a different model to fund long horizon, slow growth innovations which are quite common in agriculture. This model is not new and has been around for quite some time. It is called the Merchant Banking Model. It was used to fund different projects by the Medici family, and fund large projects like the Louisiana purchase, the Suez Canal, and the railway system in the 19th century in the US.

Steve has recently launched a newsletter called the "The Business of Science". The newsletter will feature "writing at the intersection of technology, science, human performance, and capital markets." Do check it out!

Quick definition of Merchant Banking: It blends principal risk with advice and placement. Merchant bankers take direct stakes (equity or structured debt) and arrange additional capital, unlike pure advisors. (Modern U.S. rules even define “merchant banking investments” for bank holding companies.)

Steve and I go deep into the why, and how of the Merchant Banking Model and discuss the pros and cons of the approach.

I hope you enjoy this SFTW Convo as much as I did having it!

Summary of the Conversation

Ever wonder if the traditional venture capital model is a bit like trying to fit a square peg in a round hole, especially for AgTech? Steve Sprieser thinks so! He argues that the past 15 years of low interest rates led to a lot of experimentation, but also companies raising capital without solid commercial footing. Now, with rising interest rates and burned investors, it's time for a rethink.

AgTech, in particular, struggles with the VC model because innovations take ages to mature and rarely hit those mythical billion-dollar exits. Sprieser suggests dusting off the old "merchant banking" model, where patient capital (think family offices, not quick-flip LPs) and deep engagement help nurture long-horizon, asset-heavy businesses like the next Cargill or Deere. It's less about hypergrowth and more about building a sturdy, long-lasting enterprise, with a side of advisory services.

Is the Venture Capital model right for AgTech?

Rhishi: What has been happening in this space to say, we need to look at different models. Why now?

Steve Sprieser: The last 15 years were an anomalous period, not just in AgTech or venture, but at the macro level. We had persistently very low interest rates.

Combine that with monetary and fiscal policy that keeps the cost of capital low, and you get an environment that encourages a lot of experimentation. Investors could fund capital-intensive businesses. But the downside was clear: businesses raised money without reaching the solid commercial ground they needed for inflection points like IPOs or acquisitions.

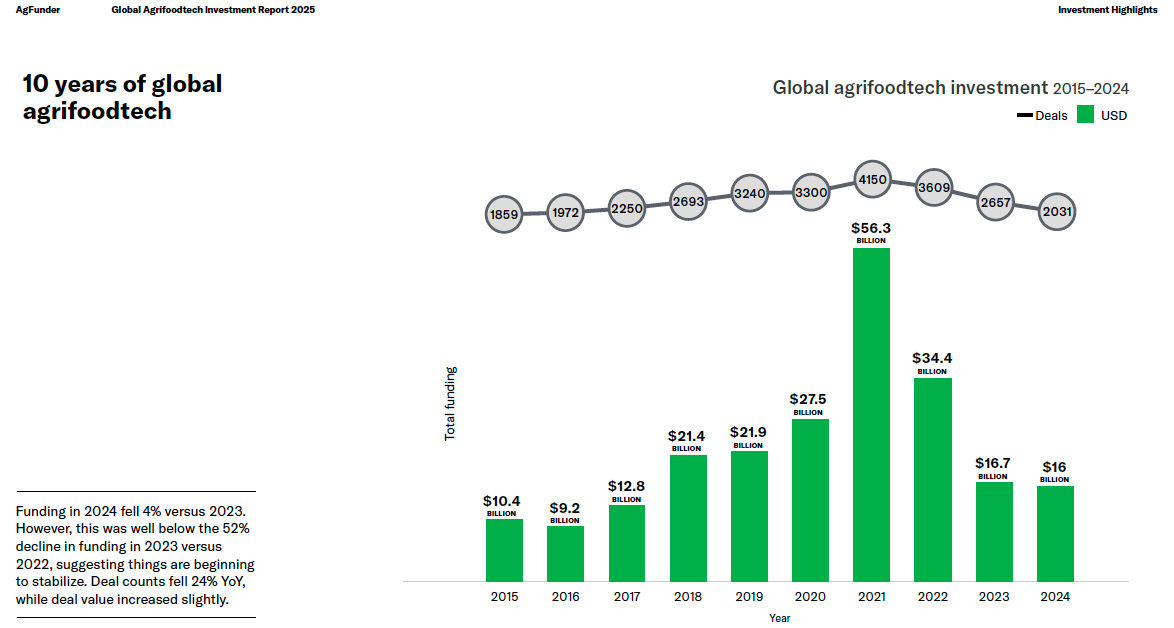

We saw this play out, especially after the pandemic in 2021 and 2022. Many companies with shaky business models went public through SPACs or got acquired at inflated multiples. Public market investors got burned. At the same time, interest rates rose, which pushed the cost of capital higher.

If you’re a capital allocator, a limited partner in a venture fund, you now have to ask: Can I really expect the same returns as the last decade? The answer is often no. Many venture funds raised between 2009 and 2021 can’t replicate that performance. Their results have been weak.

So LPs are asking tough questions: why lock up money for 10 years if the returns barely beat the S&P 500? If you’re managing money for a pension fund or an endowment, you need returns at some point. Universities and public-sector pensions are under financial stress. Illinois pension funds, where I live, paradoxically need both liquidity and strong returns. For GPs in venture, it’s a harder pitch: everyone says they can beat the market, but the results don’t back it up.

Now we’re at a point where many venture funds are underperforming, and the funds trying to raise new capital are struggling. At the same time, there’s talk about how we need to fund important innovations. But VC wasn’t designed to fund asset-heavy companies that take a decade or more to reach liquidity. Pair that with investor expectations of power-law outcomes, and it’s harder than ever to deliver.

We’ve reached an inflection point. To keep innovation moving, to grow GDP and bring critical financial and social innovations to market, we have to rethink. Maybe venture isn’t always the best model. If not, how do we tie in other parts of the capital stack to make sure innovation still gets funded?

Rhishi: Everything you’ve talked about, zero interest rates, shifting expectations, the financial pressures on universities, higher interest rates now, those aren’t sector-specific.

What makes AgTech different? If every sector is facing similar challenges, what lessons can we pull from other industries?

Steve Sprieser: That’s a great point. And it’s not unique to agriculture. The challenges are macro. Venture is just a subset of private equity, and the entire industry is feeling the pressure. Traditional PE is running into the same issues. Outside of AI, almost every sector faces these headwinds. And even in AI, there’s debate: is it hype, or can these valuations really hold?

Within AgTech, let’s go back to that macro picture. There’s an uncomfortable historical reality we don’t talk about enough. Over the last 20 to 30 years, even with more capital flowing into early-stage ventures, the number of people actually starting companies, or at least getting funded with venture capital, has stayed roughly the same. Year over year, it’s not statistically different. So on one side, you have a fixed pie of entrepreneurs. I’ve been one of them multiple times.

But the pie is fixed on the other side too. Sequoia ran the numbers internally a few years ago.

I ran them myself. If you look at exits above a billion dollars, IPOs or M&A, the data goes back to the early ’80s. For the last 25 years, the number of companies clearing that threshold has stayed roughly flat.

Now zoom into AgTech. Over a 20–25 year period, the average number of acquisitions above a billion dollars is basically zero, maybe one. So making the mythical power law work in AgTech is incredibly hard. Investors, both inside ag and generalists, looked at Monsanto’s acquisition of Climate Corp and at the valuations of high flyers like FBN and Indigo. They assumed AgTech was primed for building large-scale, venture-backed companies.

What they missed is that AgTech companies take much longer to reach fair market valuations at those levels. When they didn’t deliver in the timeframes investors expected, a lot of capital fled the sector. Money shifted not just into other asset classes, but into venture sectors that promised quicker exits and faster returns.

So we see macro challenges, but AgTech has its own unique hurdle: companies rarely deliver power-law outcomes. Even when there is an acquisition, the price is often in the low to mid nine figures. For a venture investor, underwriting that return profile doesn’t make sense. That raises the hard question: is this really a venture-backable company?

If the answer is uncertain, if conviction is lacking, the sector struggles to attract funding. And remember, ag companies often operate in niche subsectors. Even under the best conditions, moving from one subsector to another is difficult. That leaves us with a sector full of companies sitting at local maximums, hoping for an exit. Which means we need to rethink how capital gets allocated in AgTech.

Rethinking the role of Venture Capital for AgTech

Rhishi: The challenge here is that it takes a long time, and a lot of funding, for a company to reach a point where it’s ready for an exit, whether that’s an IPO or a solid acquisition.

Are we seeing a broader rethink of the funding model across the life stages of companies in those sectors as well? Or is AgTech truly unique? Does it require its own distinct approach to life-cycle funding, tailored to its entrepreneurs and the companies they build?

Steve Sprieser: It’s a great question. I think what we’re seeing is a broader rethink of venture, and, frankly, the inflexibility of the model itself. There’s a great book called VC: An American History by Tom Nicholas. In it, Nicholas points out that for all the innovation VCs want to fund, their business model hasn’t really innovated. The term sheet today looks much like it did 30 or 40 years ago.

Biotech, though, has pushed the model in new ways. When I was covering healthcare and agriculture at BCG, I saw this firsthand. Biotech faces challenges similar to AgTech: long development timelines, slow feedback loops on whether a product will succeed, heavy regulatory hurdles, and acquisitions that often land in the nine-figure range.

Because of that, biotech has experimented with different financing approaches. Larger incumbents, the likely acquirers, often play a role in funding innovation early. You also see more innovative structures around asset-based lending and other forms of structured finance. ABL is just one component of that, but it shows how the sector adapted.

So I don’t think these challenges are unique to agriculture. But given that agriculture, like biotech, tends to have longer development periods, there’s a lot the sector could learn from how savvy investors and incumbents in biotech have approached financing new innovation.

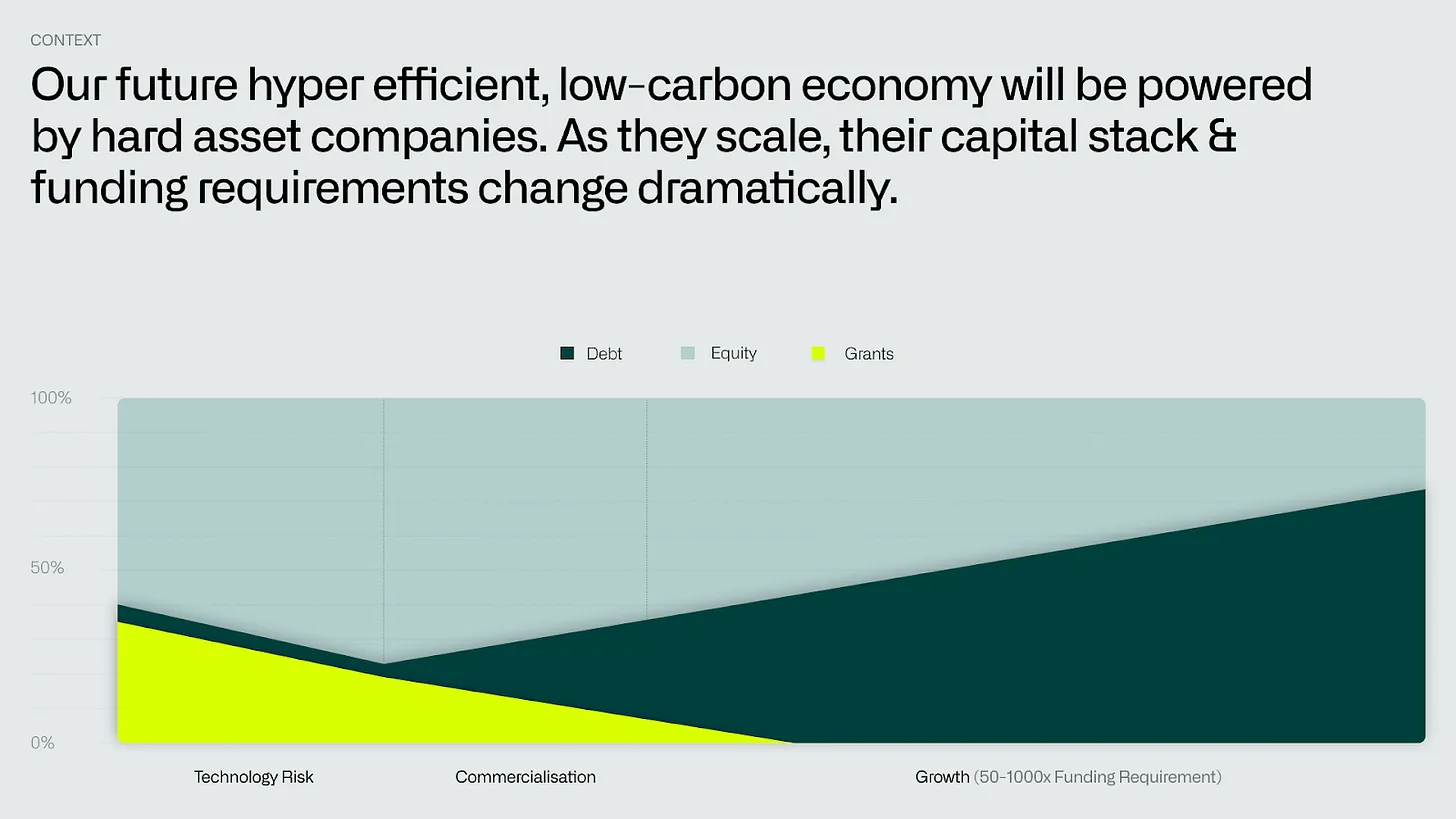

Rhishi: In Brett Bivens’ post Rise of Production Capital, he lays out a chart, showing that early on, companies focus on driving down technology risk. At that stage, most of the funding comes through equity, maybe some debt, maybe some grants. But as the technology risk decreases and you move into commercialization and growth, debt and other forms of financing start to play a bigger role.

How does that apply here?

Steve Sprieser: The typical venture model looks very deterministic, Sam Lessin at Slow Ventures calls it the “factory farmed model,” a bit pejoratively. You start a company, raise a little money from angels or through Y Combinator, then move to a seed round, then a Series A. Everything is stage-gated, sometimes down to the month. Your revenue has to hit a certain range, and once you cross $100 million or whatever the benchmark is today, you’re on track for an acquisition or IPO.

It’s formulaic. The joke is that an MBA analyst at the fund can just drag numbers forward in Excel, and the model spits out the answer. There isn’t much creativity in it.

Now compare that to sectors like biotech, or the canonical Elon Musk examples, Tesla and SpaceX. Those kinds of companies require entirely different financing. You’re literally building factories. Or in energy, you’re building turbines, infrastructure, physical assets.

Venture has mostly avoided that kind of work for a long time because it demands massive capital. If you finance all of it with equity, early investors, founders, employees, and common stockholders end up diluted to the hilt.

So what’s become more common in those situations is a different capital mix. Entrepreneurs might start with a small equity round. But when they need to scale production and get commercial-ready products into the market, they switch from equity to other parts of the capital stack, like debt.

Think about it this way: equity is great for unproven ideas, when you don’t yet know if the technology works or if the business model will hold. But once you’ve proven it works, you don’t always need more equity. For example, I’m an investor in a company in advanced materials. They’ve reached the production stage. At this point, they can show revenue projections and line up offtake agreements. When those close, they’ll need to ramp up production. Instead of raising more equity, they can turn to lenders or structured capital providers.

That model is much more predictable and de-risked. And it protects equity holders from the kind of heavy dilution you see in a hyper-growth SaaS startup in the Bay Area.

Rhishi: We’re seeing more energy startups, nuclear, defense, and others, getting funded through hybrid models. Early on, when the tech and commercialization risks are high, the capital often comes from equity. Later, as risk comes down, they transition to different types of funding. We’ve already seen this play out in those sectors.

How do we bring that kind of thinking into AgTech? What are the big roadblocks? Do VCs need to change their structures? Do they need to build new relationships or new skill sets?

Steve Sprieser: To start, it’s worth reiterating: capital allocation really does matter. Across sectors like food, ag, healthcare, energy, and clean water, the innovations we fund are the ones that push society forward. They drive GDP growth, human flourishing, and, on a global scale, lift people out of poverty and into the middle class. Funding them isn’t just about economics, it’s a moral imperative.

But bringing innovation to market isn’t enough on its own. Equally important is structuring financing so these companies actually reach the market, hit scale, and grow. Without the right capital structure, even the best ideas can stall.

If we look back, there are models that did this well. Venture capital as we know it today is relatively young. The asset class is 70–80 years old, and in its current Web 1.0-era form, maybe 25–30 years old. Originally, venture was essentially creative private equity for high-tech ventures, and it tapped into multiple layers of the capital stack.

Go back even further, and you find merchant banking models that have existed for centuries. The Medicis, the House of Baring, these firms funded high-risk endeavors by coupling services with capital. They weren’t just investors. They were tightly held boutiques that combined advisory work with direct investment, often from their own balance sheets. It was a concentrated, hands-on model.

That’s a stark contrast to today’s venture capital. Now, a VC firm raises a fund, writes checks into 10, 20, or 30 companies, and hopes the portfolio math works out. Yes, they say they’re “hands-on,” but as a founder, I can tell you it’s not the same. The older merchant-bank-style model meant sitting in the trenches. Hiring and firing executives, helping land sales, advising across the full range of challenges. Venture used to look more like that.

In AgTech, the difference is significant. Today’s funders, whether strategic investors, generalist VCs, or thematic funds, mostly operate within the same playbook venture has used for the past two decades. But given the long timelines, complex development cycles, and regulated, low-feedback-loop markets in ag, that playbook falls short.

What’s needed is a more active model, one that not only provides capital but also ties together the disparate groups venture hasn’t traditionally connected. In sectors like AgTech, success depends on more than checks. It requires deep engagement, creative financing, and a willingness to borrow from historical models that proved effective in high-risk, long-cycle innovation.

Rhishi: I was talking to a corporate VC at Syngenta. His point was this: early on, when the technology and commercial risks are high, that’s where traditional VCs can fund companies through equity. At that stage, the value VCs bring is their expertise, services, and connections. Then, once a company reaches a certain level, corporate VCs can step in, helping with distribution, scaling, and finding customers.

Steve Sprieser: Corporate venture is part of the solution. We see it in biotech and in other asset classes. But it’s not a panacea, and I don’t see it as the end-all be-all. There are a few reasons why.

First, corporate ventures still operate at the whims of market cycles. If a new CEO or CFO comes in and decides to pivot strategy, the fund can disappear overnight. I’ve seen it firsthand. On a diligence project, one of the largest corporate venture funds in the world pulled out at the last second, not because of the investment itself, but because a new CFO scrapped the theme entirely.

Second, corporate venture, like traditional VC, is tied to short time horizons. Corporate investors may say otherwise, but their ability to invest off the balance sheet, or even through a dedicated fund, still depends on the C-suite, the market cycle, and what institutional shareholders want. We’ve seen enough examples where a strategic pivot or downsizing forced corporate venture groups to change themes or shut down altogether. From an entrepreneur’s perspective, it’s hard to bet your company’s future on that.

Corporate VCs can add real value through introductions within their parent company. But when it comes to deep knowledge of capital financing, or providing the broader suite of services a capital-intensive startup needs, or being willing to get in the trenches, that’s not their role. At the end of the day, corporate venture is an extension of corporate development. It’s a useful strategic partner, but it won’t solve the wide range of challenges an early-stage, capital-intensive startup faces.

For that, corporate is just one piece of the puzzle. If you tried to rely on it alone, the shareholders would riot.

Is there a shot clock in the Merchant Banking Model?

Rhishi: In your paper, you emphasized the role of timing. Earlier you talked about the whims of the C-suite, or the short window a VC fund has to return money to LPs. You had a line that stood out: there’s no forced exit clock, and this group has skin in the game.

How do LPs approach this model when you say: there’s no forced exit clock, so I can’t tell you when you’ll get your money back?

This approach requires more money, higher management fees, to provide all these services to help entrepreneurs move from one stage to the next. Plus, you’ll need to layer in debt financing when the time comes.

Steve Sprieser: I don’t think the typical LP in a venture fund today is a good fit for a merchant banking model. If you’re a fund of funds or a university endowment, merchant banking usually doesn’t make sense. There are exceptions, you can look at private credit or certain hedge fund models where LPs redeem capital at agreed-upon time points. But in general, a merchant bank requires a very different LP base.

You need patient capital, mostly high-net-worth individuals, family offices, or entrepreneurs who’ve had exits. Or you need capital coming directly off the balance sheet, generated by the merchant bank’s own services. Why? Because of the duration mismatch. Venture has evolved into a capital velocity game: deploy quickly, generate a strong IRR, and raise the next fund in two years. The “win” is managing more money, with income flowing from management fees.

What I’m proposing is the opposite. You go to a different subset of LPs, wealthy individuals, family offices, or you use your own firm’s capital, and you say: we’re in this for 40 to 50 years. The goal isn’t to be flying a private jet in 10 years because we deployed capital fast. This is long-haul work. We’ll take real risk, with real skin in the game, and commit our own capital to back it.

The LPs who find that compelling are not institutional LPs chasing quicker returns. They’re people who buy into the mission, or families who want to park capital for decades, not years. In return, the GPs accept more risk, both personally and structurally, and make it clear the aim isn’t to become a mega-scale VC managing billions of fee income. It’s a fundamentally different model.

And the right LP base for it is high-net-worth individuals, entrepreneurs, and family offices that think in generational timeframes.

Rhishi: Take a company like Boom Supersonic. If you look at their investors, there are some VCs, but a lot of the backing comes from high-net-worth individuals. It’s a long timeline with a lot of uncertainty, including heavy regulatory hurdles. The question is: how do you bring something like that to market, turn it into a commercial business, and still return capital with growth to investors?

In the context of AgTech, what are the archetypes of businesses that fit this model?

Steve Sprieser: The benefactors here are high-net-worth individuals, family offices, or the firm’s own capital. Now, think about the entrepreneurs. In AgTech, the ones who fit this model are people who want to build very large-scale bioindustrial companies. They’re the kind of founders who are willing to take on the challenge of building a massive commodity trading enterprise or a grain merchant.

Some of the high flyers in AgTech that later soured didn’t necessarily have bad business models over a lengthy period of time. What tripped them up was the duration mismatch we talked about earlier. When entrepreneurs get constrained by capital markets, they make decisions that maximize short-term growth or showcase vanity metrics, rather than create sustainable, long-term value. They’re forced to show hypergrowth.

But if you look at the ambition behind many of these companies, it was: “We’re going to build the next Elanco” or “We’re going to build the next Corteva.” Look at Deere, it took over a century before they hit their first billion in sales. Cargill took almost that long. These businesses were capital-intensive and slow to scale, even if we can accelerate timelines somewhat today. So the right entrepreneurs for this model are laser-focused from day one on building at that scale.

Here’s where ag faces cultural issues. Many ag entrepreneurs, and I don’t want to overgeneralize, build businesses from a mindset of self-sufficiency. They want to create tools that help producers like themselves. Those are valuable companies, but they don’t need the same capital intensity as building the next Corteva, Tyson Foods, or Deere.

The companies that do require that level of capital will attract entrepreneurs who know from the outset that’s the path they’re on. And they’ll self-select into working with investors aligned to that model. On the investor side, the stakeholders, whether a merchant bank or something similar, need to be comfortable stage-gating the risks: technology risk, business model risk, and long duration risk. They need to commit for the long haul.

Traditional VC, by contrast, balks at this idea. They don’t want to see an investor taking a meaningful chunk of the cap table on day one. But this model requires exactly that: much more capital upfront, combined with both equity and non-dilutive financing. That changes the archetype of entrepreneur who thrives in this structure.

And it’s not the typical Bay Area founder profile, nor the archetype of most AgTech startups that have been funded so far. The mix of who gets funded, who funds them, and how the model works is going to look very different. But there are enough entrepreneurs out there who would embrace it, and they can’t access this kind of capital stack today because the industry is still tied to the rigid two-and-twenty venture model. A model that takes 17% equity every round and pushes companies to $100 million in revenue before they can even think about going public.

Rhishi: Merchant banking has been around for centuries. The Medici family funded all kinds of Renaissance-era ventures, including risky shipping expeditions. Today, we see firms like Andreessen Horowitz with their “platform model.” They offer services that help with hiring, connections, marketing, and more.

So how do we get from there to something closer to a true merchant banking structure? What’s the right starting point? Is it one entity evolving, or is it a set of players coming together to form an ecosystem that supports companies across the full capital stack for the next 20 years?

Steve Sprieser: I don’t think traditional venture is culturally set up to do this. You’re seeing a bifurcation in asset management: the haves and the have-nots. On one side you have Andreessen Horowitz or General Catalyst, who literally bought a hospital in Ohio to support their healthcare focus. That’s not venture anymore. That’s asset management. It looks more like a Blackstone or KKR than a VC firm. If your company is legible to them, either intrinsically or extrinsically, it’s not that hard to get funding. You’ve got growth, or you’re the archetypal founder out of Stanford or MIT, and the capital is there. It’s like going to Citi or JPMorgan for a loan.

The merchant bank model is different and it is boutique. It might start as an advisory firm, then slowly invest some of its own capital, then take on a few carefully curated LPs. That’s a very different approach. Venture, by contrast, has overdosed on low-capex companies, too much software in the diet. And when that’s been the prevailing model for four or five market cycles, it’s very hard to retrain the muscle memory.

When I bring this up to friends in the Valley, the reaction is visceral: “We could never do that.” I ask why, and the answer is always: “Because our LP agreement says we only invest in these kinds of companies, at these stages, in these geographies. And it has to be equity.” To which I respond: if you’re that bound by your LP agreement, to the point where you’re not making money for your LPs, you’re in the wrong profession. And that’s why so many venture funds today are posting poor returns. I also think LPs are at equal fault here, with their rigidity perpetuating this cycle; many look at venture as one single bucket, like they would for private credit, bonds, or public equities. This creates a rigidity in the venture model on what can and can’t get funded.

The merchant bank model flips that. It says: we’re going to have a broad remit with our LPs. We’ll invest across asset types. We’ll target multiple forms of creative financing. Some groups are starting to edge into this through “special situations” financing, but that’s only halfway there. Traditional VC as an asset manager just isn’t culturally suited for it. They’ve trained their muscle fibers on a completely different model, and it’s tough to switch.

Incentive alignment

Rhishi: Early-stage employees join startups for a mix of reasons. Some are deeply passionate about the mission and want to work in that space. Others see it as a great learning opportunity, because startups expose you to many different skills. And for many, there’s also the financial upside: if this company gets big, I could make real money.

In a model without a fixed exit timeline, what’s the story for employees? Yes, secondary markets exist, companies like Stripe have stayed private but still offered ways for employees to get liquidity. But what would an entrepreneur say to a potential hire? How do you pitch them, beyond the mission, on the financial upside?

Steve Sprieser: I think it’s important to be clear: having a timeline still matters. This is not a nonprofit. These companies have to grow, and they need a path forward. But is the 10-year horizon of a traditional VC fund the right one? Probably not.

The lack of exits in the space shows that. Still, it’s too far to say growth doesn’t matter. In fact, it’s the opposite, growth is essential. What’s needed is a recalibration.

A few weeks ago, at a conference in Salinas, a VC on stage said that if you’re not growing at 10x hypergrowth in AgTech, you’re getting left behind. That mindset is fundamentally at odds with how this industry works. Yes, entrepreneurs should move faster. But benchmarking AgTech or biotech companies against an AI wrapper company with negative gross margins is absurd. If that’s your approach, you shouldn’t be in asset management.

The reality is, for many of these businesses, Tesla, SpaceX, biotech firms, growth doesn’t follow a linear curve. It happens in step functions. Biotech entrepreneurs, for example, are often deeply mission-driven scientists. They’re ambitious, even greedy in the best sense, but they understand the long timelines and the need to de-risk methodically.

The same is true in advanced materials, energy, and other capital-hungry sectors. If you capitalize them the right way, you don’t have to dilute everyone to the bone. Employees don’t end up holding a few basis points of equity by the time you get to a Series B. Instead, you give the company more degrees of freedom, the ability to build on a stronger foundation, to grow meaningfully, to gain real market share, and to actually reach the public markets.

This isn’t about funding “nice” low-growth businesses that will never scale. It’s about funding ambitious, capital-intensive companies in a way that de-risks them appropriately, minimizes unnecessary dilution, and still positions them for meaningful growth and scale.

Rhishi: Imagine 50 companies get funded through this model and go through the process. Looking out 20 years, there are two related questions.

First, would a merchant banking entity still think in terms of the power law, the way traditional VC does? Is that mindset part of the model, or is it fundamentally different?

Second, let’s take a hypothetical. Suppose 20 years from now, none of the 50 companies break out. None become truly large, and LPs lose a significant amount of money. What would be the reasons this model didn’t work? What risks does the model face that we need to think through now, and what safeguards or structures need to be in place to make it work?

Steve Sprieser: It’s a great question. Let me take the power law piece first. I’m not a believer in the power law as it’s usually framed. There are a lot of nuances. The model I’m describing works for companies that may show some power law dynamics, but are really better suited to stage-gated financing, companies with very ambitious scale and size goals.

If you think about venture or new company formation as a Pareto distribution, most companies return between zero and 2–3x. Then you have a few that deliver 1000x hypergrowth outcomes, usually software. And within that, there’s another fraction of companies that can become true category creators. But they require enormous capital and patient timelines.

To fund those kinds of businesses, you need discernment. Ideally, your aperture is wide; you’re seeing every deal in the sectors you operate in, perhaps even providing advisory services to many, but only making equity bets for a very, very select few. You need to ask: where can this technology eventually go? Can it evolve into a general-purpose platform? Could it command massive contract sizes with customers? And you need entrepreneurs who self-select for that ambition, such as bioindustrial or hardware founders who want to build the next wave of massive, transformative companies.

On the other side of the model, merchant banks can still generate meaningful income through services. Historically, they provided everything from tax planning to deal advisory. In this context, services could include helping companies with M&A, syndicating financings, or providing broader transactional support. That provides a steady income, even as you make concentrated, high-risk bets. Syndicating the financings also reduced some of the concentration risks and capital commitments required by any one fund. Merchant banks in some cases would double- or triple-down throughout the company lifecycle; in other cases, they might concentrate a large amount of capital on growth-stage companies. In this case, that can help de-risk the odds of early-stage technology failure.

It's important to note that an additional safeguard is being actively involved with these investments, which can include hiring and firing of management and helping close major sales or partnerships; this is much more hands-on than the current VC model, but provides much greater visibility into company performance and decisions that need to be made. That level of involvement is historically what VC was, such as Sequoia's involvement with Cisco or Kleiner Perkins' involvement with Genentech.

But this model isn’t suited to every startup. It won’t work for highly deterministic software companies. And it may fail outright if you back the wrong invention or entrepreneurs without the patience for a 10-, 20-, or 30-year journey. That’s the duration mismatch again. Too often today, entrepreneurs flip companies quickly to big tech for a payout. I don’t blame them, but that doesn’t fit a merchant banking model. Here, you need founders with an Elon-level ambition, people aiming to build truly transformative enterprises from day one.

This isn’t about funding niche AgTech tools for a small slice of citrus farmers. It’s about financing the next ADM. The risks are still high, but you stage-gate capital carefully. Equity is reserved for unproven technology risk. Once the business has assets, a factory, machinery, production capacity, you bring in debt or asset-based financing. Biotech has made this work already. The opportunity is to bring that discipline into ag and other capital-intensive sectors.

Power law outcomes help, but they’re not required on an arbitrary time horizon. The real goal is to minimize downside risk while leaving room for asymmetric upside. Done right, this model allows companies to build on timelines that fit their industries, without the artificial constraints of today’s 10-year venture fund cycle and LP return requirements.

Rhishi: Steve, thank you for your time today. I appreciate your deep thinking on this matter. We need to continue to have these conversations, if we want to tweak and change how innovation, which is sorely needed, gets funded for AgTech, while creating good outcomes for everyone involved within the ecosystem.

References

Given the importance and nuance of this topic, here is some additional reading, if you want to go deep. Most of the reading recommendations come from Steve.

I told you he was a nerd!

Articles

- “How the Medici Family innovated banking systems to better manage their business?”

- The Valley of Death and the Business of Asset Management

- Andrew Lo - New Funding Models for Biomedical Innovation

- Kyle Harrison's blog posts: (The Puritans of Venture Capital, Venture Capital Unbundled, Playing Different (Stupider) Games, The Unbundling of Venture Capital, VC Contagion, Surviving The Death of Venture Capital, The Unholy Trinity of Venture Capital)

- Dan Gray's blog Credistick (especially his pieces on Venture Banks and Risk Capital)

- Packy McCormick's Not Boring blog (Capital Intensity Isn't Bad, The Techno-Industrial Revolution)

- Brett Bivens' blog (The Rise of Production Capital, The Production Capital Mosaic)

- Category Creation & Capital in Technology

- Venture Goes Multi-Product

- Agglomerators vs. Specialists

Books

- “The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank” by medieval economic historian Raymond de Roover (Sept 1999)

- Andrew Lo's book: Healthcare Finance: Modern Financial Analysis for Accelerating Biomedical Innovation

- History of the early days of VC:

- Merchant banking and classical models for funding new ventures:

- The Merchant Bankers

- Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America

- The Last Tycoons: The Secret History of Lazard Frères & Co.

- Financier: The Biography of André Meyer: A Story of Money, Power, and the Reshaping of American Business

- High Financier: The Lives and Time of Siegmund Warburg

- Dealings: A Political and Financial Life

- The House of Rothschild

- The Man Who Tried to Buy the World: Jean-Marie Messier and Vivendi Universal

- Inside Money: Brown Brothers Harriman and the American Way of Power

- The Last Partnerships: Inside the Great Wall Street Money Dynasties