The Billion-Dollar Problem Big Ag Ignores

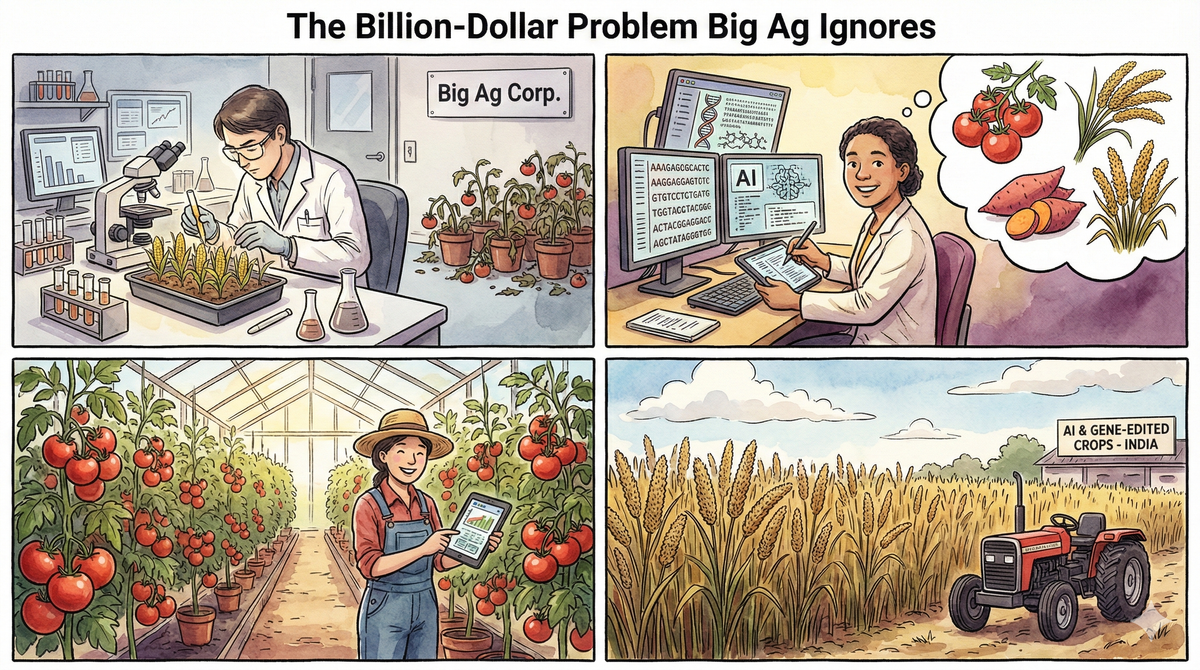

How a Startup Spun Out of X Is Using AI to Revolutionize Crop Genetics

Programming Note: The year-end AgTech Alchemy event will be at the beautiful Shapeshifters Cinema on December 18, 2025, in Oakland, California. I will be in Dubai on December 9th for World Agritech Dubai. If you'd like to meet in person in Dubai, please send me a note.

I came to know Brad Zamft when I was working at Mineral at X, the moonshot factory. Brad was working on a sibling project around using AI for genetic improvement in crops. The project is now called Heritable Agriculture, an independent company outside of X. Brad is a physicist by training, but transitioned to plant biology over a few years.

Brad has a bold vision to make genetic improvements in crops much more affordable. These genetic improvements can result in higher-yielding crops, spare agricultural land and deforestation, and result in nutritious and drought-resistant crops that use fewer resources.

I hope you enjoy this conversation as much as I did having it, and hopefully Brad’s passion comes through it.

Summary of the Conversation

Brad Zamft discusses the evolution of his career from physics to plant biology, the challenges and opportunities in agricultural innovation, and Heritable's mission to revolutionize crop genetics using AI.

We discuss how the convergence of genetic data, combined with powerful AI tools, can lead to a golden age of low-cost genetic improvements, especially for a wide variety of crops that are typically ignored by the world's agricultural behemoths, which focus only on corn and soy. Brad and I talk about how it could be transformative for what’s possible in the Global South with better genetics for underserved crops and the potential impact on global security and health.

Rhishi: You trained as a physicist, not a plant biologist. How did that transition happen? How has your physics education shaped or helped the work you’re doing now?

Brad Zamft: I chose my undergraduate degree when I was around 16. Back then, I thought I wanted to be the next Albert Einstein. I really loved physics in high school. I’m a conceptual thinker; I think in pictures. And the way biology was taught in high school, at least when I was there, didn’t click with me. It mainly involved memorizing organelles and rote facts, which I didn’t enjoy and didn’t do well in. Physics, on the other hand, was all about drawing arrows on free-body diagrams. That resonated with me.

But then I got to college, and it gradually became clear, though it took me four years to admit it, that I wasn’t going to be the next Einstein. I was in over my head. That realization led to a bit of an existential crisis.

After I graduated, I did a round-the-world backpacking trip. I went to Cambodia, rural villages in China, and Jordan, for example. That experience completely changed my life. I became fascinated by the diversity of people, perspectives, and ways of living around the world.

That’s when my mindset shifted. I decided I wanted to devote my life to making an impact and serving people who are less fortunate than me. I had already been accepted into the UC Berkeley Physics PhD program during that trip. So I came up with a grand plan: I’d join the program, get a master’s in physics, take all the pre-med classes for free, then become a doctor. My goal was to join Doctors Without Borders and work in war zones and underserved communities.

But once I started taking those biology classes, I got really fascinated with engineering biology. That shifted my path again. I dropped the med school plan and finished the PhD.

After that, I joined George Church’s lab as a postdoc, which got me into bona fide synthetic biology. And honestly, I think physics prepares you surprisingly well for many fields. There are physicists doing biology, linguistics; you see them everywhere. That kind of quantitative, first-principles training translates well across disciplines.

Everything is becoming more quantitative now. And having that strong foundation in quantitative analysis has been one of the biggest assets in my career as a biologist.

Rhishi: You and I both worked at X, the moonshot factory. X has undergone significant change over the past few years. X follows a particular model of innovation. How well did the X model work for what you were trying to build? What were the pros and cons of working within that framework?

And if you were in Astro Teller’s shoes, what tweaks would you have made to give a company like yours a better shot at success?

Brad Zamft: I can really only speak to the version of X I experienced, which was also the version you experienced. There was an earlier era of X, the one that produced Waymo and Verily, when budgets were enormous. Then came the X we were part of, where budgets were more modest. And now there’s today’s X, which I don’t feel qualified to comment on.

But what’s remained consistent throughout is Astro Teller’s vision of a moonshot. I think that vision is essential. The world needs it.

Alphabet needs it. Companies like Alphabet have to disrupt themselves because if they don’t, someone else will.

Even a company with a technological moat as deep as Alphabet’s, your phone, your computer, your search history, your GPS location, and access to almost every kind of data, can get caught off guard. Five years ago, if you’d asked me whether anyone could ever touch Google in the search business, I would’ve said no way. They had everything: data, infrastructure, dominance.

And then along came ChatGPT.

That’s what these disruptive moments look like. And even the most prominent players, Alphabet and Microsoft, have to sit up and pay attention.

In my view, that’s the core purpose of X: to build things that have the potential to disrupt the Alphabet from within. And beyond that, from a societal standpoint, we need people working on ideas that seem a little bit crazy, not impossible, not violating the laws of physics, but bold and far enough that you couldn’t fund them in a traditional industrial R&D setting.

We also need that work to stay focused on impact, which is something academia sometimes loses sight of. That’s why the world needs X, and it needs X-like organizations around the globe.

Where Heritable is today is a direct result of X. We wouldn’t be where we are now without the patience, the ambition, and the audacity that X made possible. I have no regrets. I have nothing but appreciation for X. I hope it continues doing what it does for a long time to come.

So spinning out Heritable, and letting it raise capital from investors who understand ag, who have the right connections and context, that’s the right move.

And honestly, I wouldn’t change anything about Heritable’s path. It unfolded the way it needed to. And I’m proud of that.

Rhishi: If someone were walking down the street and asked you, “What’s Heritable?” how would you explain it in plain language?

Brad Zamft: When I explain it to folks on the street, I say this: we use artificial intelligence, along with the revolutions happening in DNA and RNA sequencing, remote sensing, and satellite imagery, to help everyone grow better crops.

Our goal is to improve all crops across all locations and land types using the combined tools of AI and biology. That’s the grand vision. But we have to focus, especially as an early-stage startup. So we’ve gone where the customer traction is strong, where we’ve found the right partners, and where the opportunities are clearest.

Right now, that’s in vegetables, and, believe it or not, in forestry.

Forestry represents a massive opportunity. It’s been largely underserved, mainly because of its long improvement timelines. But that’s precisely the kind of challenge we’re built to take on. At Heritable, our mission is to accelerate those timelines and reduce the cost of crop improvement. Forestry is a perfect example of a high-impact space that desperately needs those efficiencies.

Your audience probably knows this already, but there’s a massive drop-off in resources when you move away from corn and soy. Everything else, whether it’s leafy greens, brassicas, or root vegetables, gets significantly less attention and funding.

That’s why we’re focused on the spaces where modern computational techniques can make the most significant difference: in crops and geographies that matter profoundly for nutrition, food security, and climate adaptation, but haven’t yet seen the full benefit of today’s genomic and AI-driven tools.

Rhishi: When I worked at Bayer, corn and soy were the king and queen crops, however you want to label them. Everything else tends to be treated like a stepchild. Corn and soy is just a bigger business, plain and simple. Also, the cost of bringing a new genetic variety to market isn’t all that different whether you’re working on corn or a smaller crop. From a company’s perspective, it makes perfect economic sense to focus where the returns are highest.

So that brings me to you: How are you solving that problem? Is your secret sauce that you’ve figured out a way to develop new genetic traits much cheaply? Because if you can change the economics, then maybe you can change the entire strategy.

Brad Zamft: It comes down to making crop development cheaper and faster. That’s our core mission. At the highest level, we want to improve all crops in all geographies using biology and AI. But just one level down, our focus is on making crop development more affordable and more efficient.

But when you look deeper into agriculture, you realize there are thousands of other players, smaller companies, research institutions, breeding programs, who would love to access corn-level genetic improvement, but simply can’t afford it.

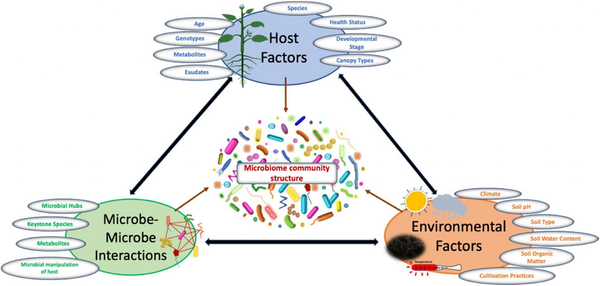

We have more biological information now than at any point in history. Twenty years ago, if you sequenced 50 bases of DNA, you could publish in a top-tier journal. Today, sequencing an entire metagenome might not even be enough for publication. We’re swimming in genomic data.

At the same time, we’ve seen similar leaps in how we measure and observe the world: satellites, drones, weather stations, soil sensors. We can capture environmental context at incredible resolution.

The key is integration: bringing together biological and environmental data and making it actionable.

For the first time, we have the computational tools to analyze these massive, multimodal datasets and extract insights that just weren’t possible before. The tools have changed. And that’s precisely where Heritable comes in. We’re challenging that assumption. We’re saying: now is the time to go beyond corn and soy, because we finally have the means to do it.

Rhishi: When you talk about crop improvement, what are the specific dimensions you’re targeting for improvement? And what are some of the most in-demand or highest priority traits you’re focused on?

Brad Zamft: We currently offer three products.

The first is genomic prediction. We take the entire genome and predict how that plant will perform. What makes our approach unique is that we incorporate environmental data: soil, weather, and climate. This lets us create a digital twin of a plant, a simulated version of that plant, at a 10-meter resolution, anywhere in the world.

The second product is designed for situations where you don’t fully understand the genetic architecture of a trait. If you don’t know what genes control a trait, we use multiomics, a complex mix of molecular data types inside the plant, to identify the key genes responsible.

But even knowing the genes often isn’t enough. If you already know the genes, the question becomes: How do you control them? How do you turn them on or off? How do you activate them in specific tissues or under specific stress conditions?

That’s where we leverage large language models. We use them to pinpoint the specific DNA bases you can edit to control gene expression, timing, location, and conditions.

Now, to your question about traction: where are we seeing the most demand?

The first product, genomic prediction and breeding, has generated by far the most interest. And it’s not just because we can improve genomes; we also model the environment. That opens up a whole new dimension: not just how to change a plant, but where to place it.

Let’s say you want to expand your geographical footprint. Maybe you're facing climate risk, geopolitical risk, or you just want to optimize where you grow different varieties. Our system helps identify which environments are best suited for which genomes, and vice versa.

We’re seeing a lot of demand from companies and growers who want to make those strategic decisions with more confidence.

Rhishi: One of the fundamental challenges in agriculture is context, the agroecological conditions, the soil type, the rainfall patterns, and everything else. All of those factors vary, even for the same crop.

Seed genetics are developed by optimizing for a broad set of conditions, which work well in major production zones like northern Iowa. For example, you design a corn variety with a specific relative maturity that performs well across a large region.

You could imagine a world where every field has its own optimized seed. Maybe every plant has its own genotype. That might sound crazy, but conceptually, you could go that deep if the economics and tech made sense.

Brad Zamft: I do think it’s worth dreaming for a moment. Let’s go back to our X days, where thinking exponentially was encouraged.

There’s a future, if we think in exponential terms, where the produce you buy at your local farmers market comes from genetics that were custom-made for that exact farm. The crop ripens the day before the market. It’s fresh, it’s nutritious, it’s high-yielding, it’s cost-competitive, and it’s sustainable.

And here’s the thing, we already have genetic segregation. I’m not even sure we need to make custom seeds for every single person. That would be death by a thousand paper cuts, the operational cost of that would crush you. But in a true science fiction future, and honestly, we are living in the science fiction I read as a kid, we’ll be able to use natural segregation, predict it, and match the right genetics to each farmer, even down to individual preferences.

More importantly, and this goes back to your roots, and to my own revelation when I was backpacking, we’ll be able to deliver competitive, high-performing genetics to smallholder farmers. That’s what could really lift the quality of life in those communities.

You're right, though operational complexity is the killer. That’s why we’re not starting there.

But we’re also not starting from the dominant paradigm either. We're not designing genetics that average across all of Iowa, because while that makes perfect sense for large seed companies trying to manage complexity, it's not what we're here to do.

It’s all about finding the right partner.

I was just in Canada two days ago. We’ve announced a great partnership with Paul J. Mastronardi, one of the largest growers of indoor vegetables. He grows year-round, primarily in controlled environments.

It’s not a smallholder farmer scenario, and it’s not an operational behemoth like corn or soy. It’s a focused use case. And even though this market is big, it’s still not big enough for the major seed companies. They’re primarily focused on field crops, such as strawberries, grown outdoors.

That’s where we come in.

We’re not chasing hyper-fragmented logistics, but we’re also not playing in the high-scale, high-commodity world. We’re working with a partner who sells massive volumes of fresh produce each year and needs better genetics to keep going.

Rhishi: I visited some greenhouse tomato operations in Canada about 12 years ago. At the time, it felt like something out of science fiction. They had all this automated vine-grown production on trellises. The tomatoes would rotate, and a lot of hydroponic work was also happening.

That might be a good segue into your business model and partnership strategy.

What’s your go-to-market plan? When you're evaluating partnerships, what’s your rubric?

Brad Zamft: We’re looking for partners who want to take the journey with us. That means real cost-sharing and real value-sharing, if I’m being honest and getting down to brass tacks.

We want to build new entities. We want to help expand your business and take you into places you can't reach right now. That could mean developing an entirely new trait that you never thought was economically feasible. It could mean entering a new region. Or it might mean taking on an entirely new crop.

But it comes at a cost. We’re building that business together.

We’re not interested in the dominant model, where you license a trait, take a 1% royalty, and the seed company keeps the rest, splitting it three ways between themselves, the distributor, and maybe the farmer. That’s not what we’re after.

We’re looking for true partners, people who want to help build new subsidiaries, new business units, maybe even brand-new entities down the line.

Right now, we’re working with Paul J. Mastronardi on strawberries. That’s a great example of the kind of partnership we want to keep building.

Rhishi: Strawberries have a pretty complex genome. One significant challenge in agriculture is that it's really hard to transfer knowledge and tools from one crop to another.

It’s not like being great at corn breeding means you can just turn around and start breeding strawberries. The skill sets, tools, and data pipelines they’re all different. It’s a whole new playbook.

So, going back a bit to the technology side, and maybe this ties into the business model too, how easy or difficult is it for you to switch from one crop to another?

Brad Zamft: I mean, we haven’t reached that point yet. Sure, there’s a science fiction future where we’ve built a simulator for all of biology, or maybe a little less ambitiously, for all of plant biology, or all dicots, or all vegetables. We’re not there today. But I do believe that kind of future will become reality. It’s just a matter of timeline.

What is here today, and what we’ve developed and productized at Heritable, is our approach. And that approach has several key components.

First, we have one of the best teams in the world at running multi-omic field trials. There are plenty of people out there who know how to collect DNA and follow genetic markers in breeding programs. But we’ve worked with other groups who say, “Don’t worry, we’ll handle everything, we’ll extract the RNA, we’ll get you all the molecular data.” And I can tell you, when we do it ourselves, it’s better.

We’ve done this over and over, across many crops. We know how to design the trial. We know how to do tissue sampling, extraction, and sequencing. We’re world-class at that.

Then there’s data cleanup, a very underappreciated step in any machine learning or AI pipeline. After that, there’s data integration, and that’s where we bring in our major differentiator: environmental modeling.

We can predict how a plant will grow anywhere in the world at 10-meter resolution, and do so reproducibly. Our ability to integrate the environment into the model is foundational and transcends crops.

That’s really the point: this approach transcends crop. Yes, there are minor differences, the tissue you sample will depend on the crop. The trait you’re optimizing will vary depending on the project. But over the last five years, we’ve fine-tuned every part of this workflow.

We’ve also dialed in the model's architecture. We’re not constantly rerunning architecture searches or asking which algorithm will perform best. We’ve learned those lessons. We know how to do this. We don’t need to relearn it every time.

Now, is the holy grail full transferability, where a model trained on corn instantly knows how to predict outcomes in strawberries? Sure, that would be amazing. But we’re not there yet. And honestly, I’m not even sure that level of transferability is necessary right now.

There’s already so much demand in the industry that we can run the field trials we need, and the cost isn’t a significant barrier. So while we’re not in the science fiction future yet, we’re delivering fundamental, scalable, high-impact tools that are working right now.

Rhishi: When I was at Mineral, getting access to data to train our models was one of the biggest challenges. How are you managing the process of getting the data you need to train your models?

Brad Zamft: Yes, everyone is still cautious about sharing their data with us, and rightfully so. But that really comes down to relationship management. It’s about finding the right partner and building trust. That doesn’t happen quickly. I haven’t had a sales cycle for under six months yet.

Reducing the sales cycle requires building trust one-on-one, but it also happens more naturally over time, once we’ve proven ourselves through successful projects. As people see that we’re a trustworthy partner, that we’re not out to misuse anyone’s data, that we work securely and transparently, those barriers start to drop.

And again, it depends on the partner. Some organizations understand that the future of agriculture will rely on specialized collaboration. You need people focused on artificial intelligence and predictive tools, and others focused on operations such as growing, packing, shipping, and distribution.

Rhishi Pethe: Let’s say you're working on a particular crop, you’ve done the genome characterization, identified the key genetic markers, and now you want to understand how that plant will perform under different environmental conditions. You need data to validate your models.

What are the most significant barriers to driving down the cost and increasing the velocity of what you're doing? For example, we saw the cost of sequencing a human genome drop by over a million-fold in about 20 years, while the speed of sequencing skyrocketed by several orders of magnitude.

Brad Zamft: Most of agriculture still has a long way to go, and we can get very far with better breeding.

Just look at corn. For 80 years, it’s shown genetic gains of about 1.7 bushels per acre per year. And that mostly comes from agronomic breeding, dihybrid crosses, and computational biology, not from GM.

After 70+ years, we’re still not done. The genetic potential of corn hasn’t been exhausted.

Now shift your focus to crops like sorghum, or even to trees. In the time we’ve been breeding corn, trees have maybe gone through five breeding cycles. There’s so much low-hanging fruit if we just improve the way we breed, especially if we incorporate environmental data better.

That’s why the vast majority of our business model is focused on breeding. There’s an enormous unmet need and massive opportunity in just doing that better.

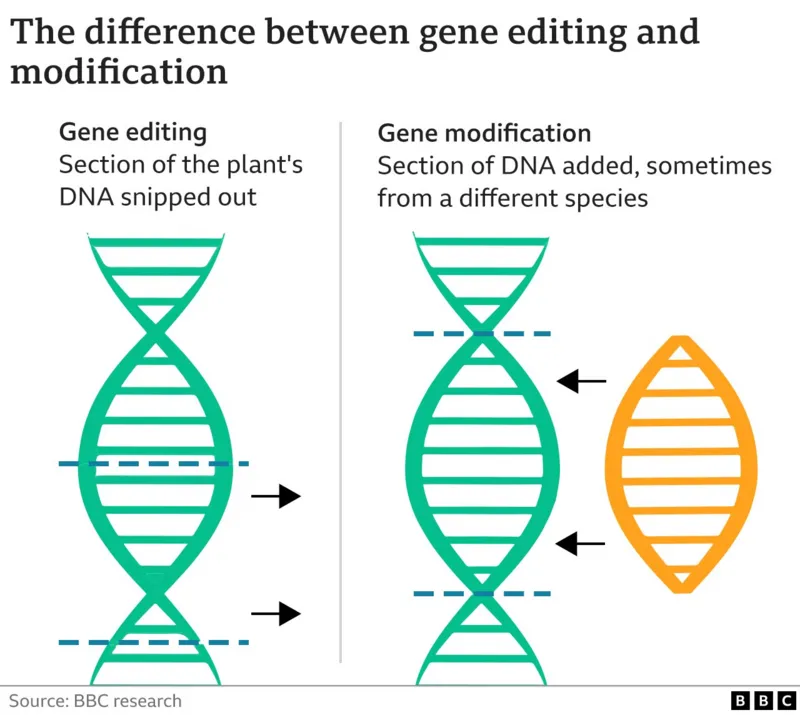

Of course, we’re happy to support gene-editing projects today when partners ask for them. But let’s look at the addressable market.

You start with everyone who uses genetics to deliver a plant product. Then you narrow it down to those who are in an industry or geography where biotech-modified products are actually accepted, either by regulators or the public. That cuts out a huge portion of the market.

Then you narrow further to those who are not only willing to take that risk but also have the resources to do it. Gene editing often requires tissue culture and lab infrastructure, which are significant barriers.

Image source: BBC Research

And it’s not always about regulation or public perception. Sometimes, the logistics and cost of implementation are the bigger reasons to hold off.

That’s why, for now, we focus primarily on breeding. It’s where we see the most potential, technologically, operationally, and economically.

Rhishi: I recently read a book titled "Globalization of Wheat." The author argues that, while the Green Revolution was undeniably transformative, breeders focused heavily on wide adaptation. She means they intentionally bred wheat varieties to perform consistently across a broad range of agroecological conditions.

The tools available at the time pushed them in that direction. And they achieved that consistency not just through genetics, but by leveling out environmental differences with intensive irrigation and heavy fertilization. That was part of the strategy: make the environment more uniform so the seed could be more uniform too.

What I find interesting about your work is that you’re not aiming for widespread adoption. Your approach seems more about fine-tuning. And in a more speculative or science fiction version of your work, it could go all the way down to the field, or even plant-level personalization.

How do you think your tools or technology could shape agriculture in the Global South?

Brad Zamft: We have to do this. We have to figure it out. No one’s solved it yet. People have tried, but the conditions have changed, and now we have the tools to give it another shot.

I’m not an expert in international development, and I don’t pretend to be. No one in the audience should take me for one. But from what I understand, there’s a critical inflection point when a subsistence farmer starts producing just a little more than what they need to eat.

That shift, from subsistence to a surplus, can be a quantum leap in someone’s life. It allows them to sell what they grow. And once they can sell, they can start focusing on other things: education, health, and improving their quality of life. So we have to figure out how to enhance the genetics of those farmers. And when we do, it will have a massive, immediate impact.

But there’s another side to the story.

Management and business structure matter. Many subsistence farmers grow open-pollinated varieties. They don’t buy seed. So how do we monetize improved genetics when there’s no established genetics industry? No supply chain? No infrastructure?

This is where we need collective thinking. This is where the whole community, especially people more qualified than I am, needs to step in and ask: How do we build an industry model in which a farmer can pay for improved seed and make a return on that investment?

And maybe the key isn’t starting with the lowest-resourced farmers. Perhaps the answer lies in starting with the middle or lower-middle segment, those with a bit more capacity to adopt, adapt, and build momentum.

It’s not a solved problem. But we’re doing our part. And for me, this is one of my life’s missions: to help those less fortunate than us improve their quality of life through better crops, better tools, and better opportunities.

Rhishi: If Heritable is as successful as you hope it will be, what tangible impact would you hope to see? What would make you say, “Yes, we did something that mattered.” Feel free to touch on any areas that matter most to you, whether it’s forestry, nutrition, climate resilience, or something else entirely.

Brad Zamft: As we continue to de-risk our technology, we’ll move closer to that science fiction future we talked about earlier. And when we do, we’ll unlock a world of applications, because plants truly are miraculous. They're solar-powered, carbon-negative, self-assembling machines. If you get the genome right, you can literally put a seed in the ground and return later to find that you’ve grown the function you wanted.

If we succeed, we’ll see sustainable, diversified forestry, not vast monocultures of genetically identical trees planted in rows, but ecosystems that reflect a deep understanding of biodiversity and environmental dynamics, supported by genetics that back it up.

In row crops and vegetables, we’ll have nutritious food that competes on price with less healthy options. You’ll be able to buy strawberries that taste amazing, and your kids will actually prefer them over Cheetos. And they’ll be priced competitively. You’ll have supply chain certainty, especially in indoor agriculture, where one of the main goals is year-round, local production. So yes, you’ll have strawberries all year, and they won’t have to travel 3,000 miles to reach your plate.

And then we can really begin to embrace science fiction.

Ten years from now, we’ll have dropped the technical and operational barriers enough that we can start sequestering carbon at scale, not through inputs or amendments, but through the very plants we’ve designed. These plants, these “machines”, will pull CO₂ from the air and push it into the soil, rebuilding our soils automatically.

We’ll also have food as medicine. In fact, we already do. Many of our pharmaceuticals are plant-derived. But we’ll go further. We’ll optimize plants to express those medicinal compounds more consistently and at higher levels. You'll eat a salad not just for nutrients, but for specific health benefits, because we’ll have designed that into the plant itself.

Everything becomes possible once we remove the barriers and accelerate the timeline for improving crops across species, across systems, and across the world.

Rhishi: That's a very inspiring vision, Brad. Thank you for your time today, though I do love my Cheetos!