The diminishing middle

Middle of the pack crops struggle to keep their acres in California

Welcome to another edition of SFTW Plus. SFTW Plus is the paid version of “Software is Feeding the World” and includes all Sunday newsletters, SFTW Convos series, Scaling Innovation series, and access to the archives.

Agrifood leaders subscribe to SFTW Plus to stay abreast of the latest thinking, frameworks, and future trends on how technology can be a force multiplier for your organization. SFTW Plus subscribers routinely use it to make more informed decisions, influence their strategy, sharpen their execution, and get an edge in their professional careers.

Happenings

- I co-hosted (and guest hosted) a [History] of Agriculture podcast episode with Tim Hammerich for the Future of Agriculture podcast series. The topic was based on a book by Neil Dahlstrom called “Tractor Wars” which explored the early history of the invention, and adoption of gas powered tractors in the early 20th century.

- Over the last few weeks, I have started offering corporate subscriptions to different organizations. A corporate subscription comes with a significant discount, full access to SFTW Plus and is paid for by your organization, typically through their training and education budgets. If you would like to sign up your organization for a corporate subscription program, just reply to this email.

The phenomenon of the “hallowing out of the middle class” in the US has been extensively studied. There are many reasons to explain the stagnation in wages for the middle class. The adoption of automation has been one of the main reasons for the loss of jobs over the last few decades, especially in manufacturing.

On the other hand, the lack of automation might create significant challenges for keeping the middle of the pack crops to continue to grow in California. (The “middle of the pack crops” are crops with a market value which is not in the top quadrant but somewhere in the middle). It could hollow out the middle crops due to lack of automation, instead of presence of automation.

The diminishing middle

Last week, I was driving around Merced county in California visiting some growers. It is a very agricultural county in California with a lot of almond trees, and dairy operations. The setting was beautiful as I drove down county roads, and the weather was a perfect 70 degree Fahrenheit. I visited a few sweet potato growers to understand some of their challenges.

A farm in Merced County, California (photo by Rhishi Pethe)

But when you go talk to growers there, you realize there are significant challenges ahead, depending on which crop they are growing.

Merced is the fifth biggest county based on the value of agriculture production in the state of California. For reference, California is the biggest state in terms of the value of crop cash receipts (2022 data) of $ 55 billion, with Iowa at number two with $ 45 billion. Merced county’s total value of agricultural production in 2022 was $ 4.5 billion.

According to the California Agricultural Statistic Review 2022-2023,

California’s top 20 crop and livestock commodities accounted for $47.9 billion in value in 2022. Thirteen commodities exceeded $1 billion in value in 2022. The cash receipts of 14 of the top 20 commodities increased in value in 2022, compared to 2021. Of the top 20 commodities, chicken eggs, broilers, and lettuce showed the largest growth in cash receipts during the year.

Outside of animal products, the top crops in California are grapes, almonds, lettuce, berries, pistachios, tomatoes, carrots, rice, oranges, broccoli, tangerines, and lemons.

Once you go past the top 10 crops in California, the production value of each crop is below a billion dollars and then it drops substantially

For example, the total crop value of sweet potatoes in California is $ 280 million based on 2022 data (with $ 243 million in Merced county alone). There is very limited automation in sweet potato production, with significant human labor required for planting, cultivation, harvest, and sorting.

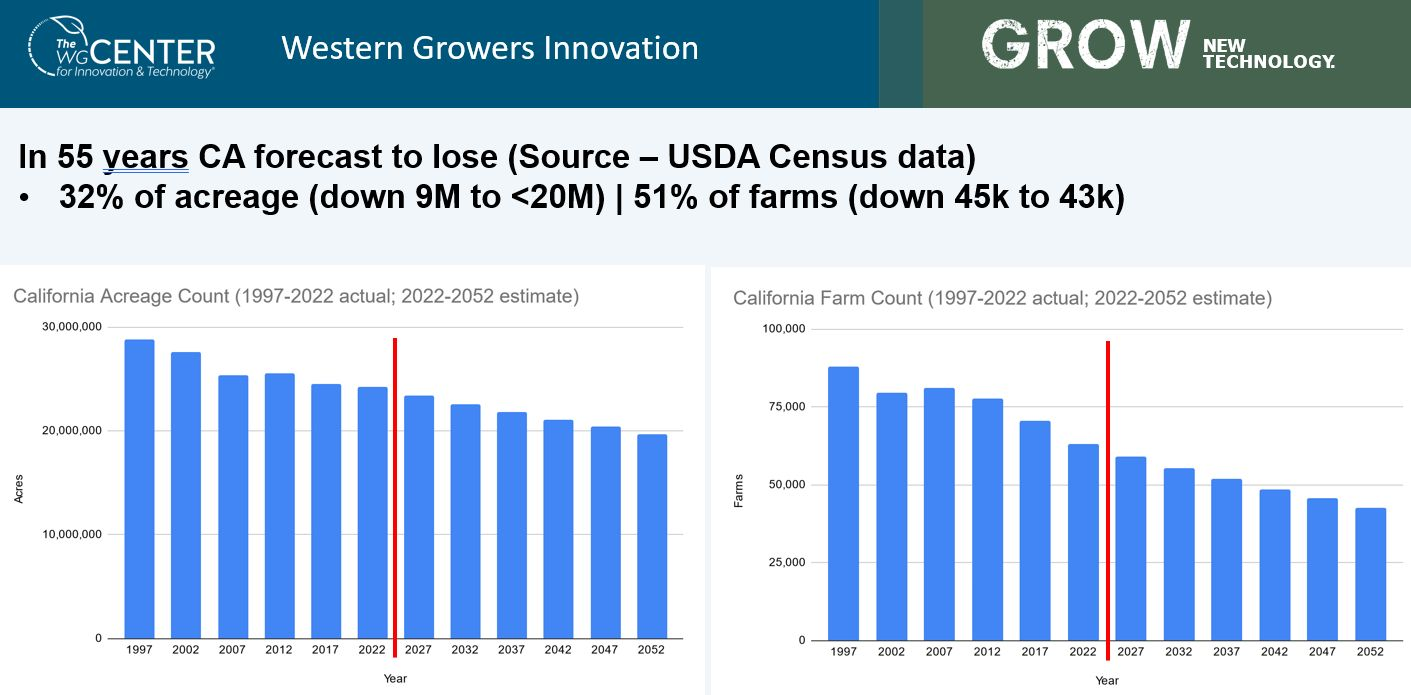

As has been documented many times by folks like Walt Duflock, and others, the cost of labor keeps going up in California, and along with it the difficulty of finding labor also keeps going up. Along with labor and other regulatory issues like SGMA (Sustainable Ground Water Management Act), it has resulted in a loss of a third of California acres over the last five decades.

There are many crops which are very difficult to automate and require human labor, especially for harvesting. This is especially true for "middle of the pack” crops. Given the unique requirements of each crop, even if you are able to automate the harvesting operation for a given crop it does not easily translate to other crops.

There are certain crops which are easy to automate or have large enough value, are able to sustain their acreage (or increase it) in California, but many crops which are difficult to automate or have small to medium market value are decreasing in acreage and do not attract enough investment to automate.

For example, the automated mechanical harvester for sweet potatoes cannot be used by other crops.

Given the total market value of sweet potatoes in California is only $ 280 million, it will be very difficult to get funding from a traditional VC to build a sweet potato harvesting robot.

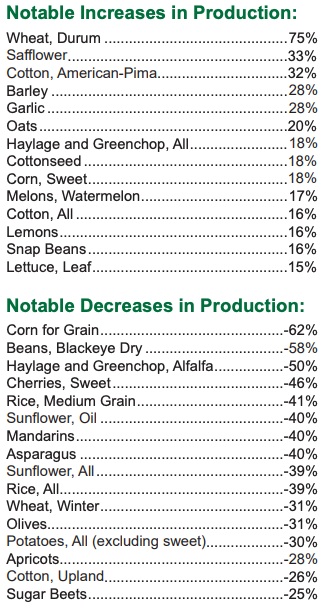

Source: California Agricultural Statistic Review 2022-2023 (change compared to previous year)

Crop position on the automation spectrum

There are four main factors which determine where the crop lies on the automation spectrum from a fully manual operation to fully automated.

Market Destination (Processing vs. Fresh)

This is the primary determinant of harvest automation feasibility. Processing markets tolerate bulk handling and prioritize efficiency, enabling the use of robust, established mechanical methods. Fresh markets demand selectivity, gentle handling, and cosmetic perfection, requiring sophisticated (often developmental and costly) robotics.

For example, one of the sweet potato growers said that an existing automated harvesting machine for sweet potatoes damages the skin of the sweet potatoes enough to reduce its usable life, makes it difficult to sell in the fresh market, and forces you to sell quickly or sell it to the processing market which fetches you lower prices.

Crop Characteristics

The physical nature of the crop is critical. Durability (e.g., nuts, processing tomatoes bred for toughness) allows for more vigorous mechanical handling. Fragility (e.g., berries, fresh tree fruits, asparagus spears) necessitates gentle, often robotic, approaches.

Growth habits also matter. Crops with uniform, determinant ripening (like processing tomatoes) are easier to bulk harvest than those requiring continuous, selective picking over weeks or months (like strawberries, asparagus, table grapes).

For example, asparagus needs multiple harvesting trips during a given day by a crew of people, during the harvest season. This makes the harvest process for asparagus very expensive. There are not viable automated solutions due to the delicate nature of asparagus at harvest. Asparagus also requires a significant amount of water to grow, which is a challenge in California. According to the California Asparagus Commission,

At the turn of the 21st century, California growers were farming over 36,000 acres of asparagus. In 1995, Contra Costa County harvested 20,000 acres of asparagus. In 2017, that figure dropped to a mere 1,300 acres, according to the California Asparagus Commission

Plant architecture and fruit accessibility (canopy density, fruit clustering, trellis systems) significantly impact the ability of machines or robots to effectively operate.

Economic Thresholds

Automation requires substantial capital investment. Adoption hinges on whether the technology can provide a favorable return on investment by significantly reducing labor costs, increasing efficiency, or improving yields compared to manual methods.

This threshold varies based on the crop's value, the intensity of labor required for specific tasks, and prevailing wage rates. High-cost, labor-intensive operations are stronger candidates, but the technology must still prove cost-effective.

Going back to the “middle of the pack” crops like sweet potatoes, it might require some capital investment to build an automation solution, with the challenge that the automation solution might not work in other crops, limiting its economic potential.

Technology Maturity and Reliability

The availability of proven, reliable, and efficient automation solutions differs greatly by task and crop. Technologies for processing tomato harvest or nut shaking are mature and widely adopted, while robotic systems for fresh market harvesting are largely still developmental, facing challenges in robustness and performance.

For high value crops like berries, table grapes, and large crops like lettuce, it is possible to support a high production cost operation in California, due to the higher market value and higher pricing power due to the quality and freshness of those products. This math is definitely under pressure as has been seen through the recent flight of blueberry acres to Peru from California.

It is even possible (and we see it happening) to get VC or other types of funding to reduce production costs (especially harvest, because harvesting is about 60% of the production cost in many specialty crops in California), given that these crops have a crop value which runs in billions of dollars.

But crops which are in the middle and require unique automation solutions, face a special challenge. They have to be able to supported by a different funding model than traditional VC.

They need to support a business model which works for the solution provider, and there is a way to build automation solutions at a cost which makes sense, while still providing the flexibility needed to handle the uniqueness of each crop or even each operation.

Funding model

Traditional VCs look for a few big exits within their portfolio, which more than pay for most of the investments which do not work out in a given portfolio.

Companies can potentially grow to $ 100 million in revenue in automation, but if the product cannot be adopted across multiple crops, then it will be difficult to do so, unless you are working in one of the top 10 crops in the state. There are just not enough dollars to justify a revenue and a revenue multiple, which might make it interesting for a traditional or a sector VC to invest in.

Connie Bowen of Farmhand Ventures has a slightly different approach to VC investing. VC investing always seems to be billion-dollar opportunities, which do not exist easily in AgTech due to the limit in scalability.

Additionally, unlike most venture capital firms that seek billion-dollar opportunities, I don’t. The average exit valuation between 2018-2022 was $111 million, as reported by Kyle Wellborn in Crop Life. With exit valuations more likely to be around $100 million, I still aim for significant multiples. Thus, I seek adequate ownership in capital-efficient companies, assisting them in leveraging non-dilutive capital through SBIR, NSF, and USDA programs, and prioritizing companies that can generate revenues quickly.

I think that the scalability of agtech is often limited, which is not something you typically hear from VCs. Agriculture is fragmented. There’s a significant difference even between fields in the same county growing the same crop. So, I believe there will be humans working in field agriculture for a very long time to come.

And I don’t think that is the core mission of the vast majority of venture capital funds, nor should it be. Venture capital funds exist to deliver massive returns and take huge bets. I think that we need more capital allocators with the mindset that being a multimillionaire is sufficient; there’s no need to aim for billionaire status.”

There are other ways to reduce risk and raise funding through grower investments through their co-ops or grower organizations, non-dilutive capital as indicated by Connie, and by providing hands-on support to entrepreneurs and project developers.

For example, The Reservoir in Salinas, CA has the following mission.

We cultivate trust, foster connections, and create opportunities through face-to-face collaboration, impactful events, and hands-on support. By breaking down barriers and strengthening entrepreneurial ecosystems, we empower startups to succeed—and drive meaningful change in underfunded regions. At Reservoir Ventures, we connect rural-focused startups with the resources, networks, and opportunities they need to succeed.

Reservoir’s model could help take the risk out of the system at a much earlier stage and with lower investment, and so would reduce the pressure of finding a few diamonds in the rough.

Product development

I saw three different sweet potato harvester configurations at three different sweet potato growers. Each of the harvesters had been modified by the grower to suit their operational needs, and none of them were still fully automated.

Given the uniqueness of different crops, and sometimes operations within a single crop, it is very difficult to build a product which works across all types of operations for a given crop, let alone across crops.

Due to this we have optimized potato harvesters, carrot harvesters etc. and they cannot work on a different crop type. (This is less of an issue for commodity row crops like corn and soybean.) This increases the R&D, production and support costs for any organization building automation solutions for specialty crops, especially for harvesting.

From a product development perspective, local service providers or project developers could potentially develop custom automation solutions with their deep knowledge of grower operations, crop type, local conditions, and their relationships in place.

Is there a room for more flexible models like open source solutions, which provide some basic functionality and then allow the growers (with some additional help) to modify the open source model to fit their needs?

For example, Mr. Clemmons of Ronnie Baugh tractors is open sourcing hardware design for inexpensive tractors for small holder farmers.

Having access to low cost, highly customizable agricultural equipment that is also open-source technology has the potential to benefit millions of small farmers in the developing world. But in the U.S., the idea is also gaining traction — for very different reasons.

"The diversity of a farm like this where we're growing literally hundreds of different crops — there is no one piece of equipment, there is no giant thing that we'll use to solve all of our problems. There are a lot of little instruments in our toolbox, so we want those to be as minimal as possible and as repairable as possible."

Not to mention, there's the ability to tinker with the design. Algiere says he’s made multiple modifications, cutting and welding the frame to raise the floorbed, making room for nearly a dozen different custom tools. All of these changes are shared among the growing Oggun community of small farmers.

We have seen some success with an open source model, outside of automation with the Open Weed Locator project from Guy Coleman.

The challenge with open source is with software, as many farmers are tinkerers and feel very comfortable with hacking together modified hardware, but struggle with software skills.

If the open source project can provide basic functionality for software, and provide the ability for local developers (who are not farmers) to make changes on behalf of farmers, it could create an additional revenue stream for local ambitious tech savvy entrepreneurial talent in rural areas.

Business Model

There is room for a service model based approach as we have seen in custom harvesters. Custom harvesters are owned by the service provider and provide harvesting services to growers. The grower does not have to own the harvester and so can spend more on OpEx compared to CapEx.

The company developing (and maybe even operating) the custom automation solution can spread their operational costs across multiple operations, and get access to a recurring stream of revenue which can be used to improve the product and service, and have a successful company. This would be especially true for crops in the bottom or the middle.

Key takeaways

There is a clear and significant spectrum of automation across California's specialty crop sector. Crops primarily destined for processing, such as processing tomatoes, tree nuts (almonds, walnuts, pistachios), and carrots, exhibit very high levels of mechanization and automation, particularly in harvesting and post-harvest handling. These systems, often developed decades ago and continuously refined, leverage the crops' durability and the efficiencies of bulk handling.

At the other end of the spectrum lie numerous high-value fresh market crops, including strawberries, table grapes, fresh market tree fruits (apples, peaches, cherries), and fresh market tomatoes. Harvesting operations for these crops remain overwhelmingly reliant on skilled manual labor.

The primary barrier is the critical need for selective picking based on ripeness and quality, combined with the requirement for extremely gentle handling to avoid bruising or damage. Current automation struggles to replicate at commercially viable speeds and costs.

The middle of the pack crops are diminishing in their footprint, due to a lack of automation solutions, and the challenge to build automation solutions from a financial standpoint, even if the technology exists.

The middle has been diminishing and will continue to do so, unless different approaches are adopted and scaled across funding, product development, and business models.