The False Dichotomy of Silicon Valley vs. Salinas Valley

Are VCs the you-know-who's of AgTech?

Agrifood leaders subscribe to SFTW Plus to stay abreast of the latest thinking, frameworks, and future trends on how technology can be a force multiplier for your organization. SFTW Plus subscribers routinely use it to make more informed decisions, influence their strategy, sharpen their execution, and get an edge in their professional careers.

SFTW Plus is the paid version of “Software is Feeding the World” and includes all Sunday newsletters, SFTW Convos series, Scaling Innovation series, and access to the archives.

Happenings

If you missed downloading part 1 of the GenAI report, you can still download it for free. The second part of the report is taking shape and will be out in the next few weeks. The second part will cover the value side of the equation for GenAI in Agriculture. Download the first part of the report “POC to OMG! The Realities of Deploying GenAI at the Farm Gate”.

The false dichotomy of Salinas Valley vs. Silicon Valley

If we look at the US Venture Capital industry as a whole, the VC industry has been a massive force multiplier for R&D spending, innovation, and value creation, according to research published a few years back. The AgTech industry needs to continue to figure out the types of problems which are most amenable to be solved and scaled using venture capital.

Venture capital-backed companies account for 41% of total US market capitalization and 62% of US public companies’ R&D spending. Among public companies founded within the last fifty years, VC-backed companies account for half in number, three quarters by value, and more than 92% of R&D spending and patent value.

The US did not spawn top public companies at a higher rate than other large, developed countries prior to 1970s ERISA reforms, but produced twice as many after it. Using those reforms as a natural experiment suggests that the US VC industry is causally responsible for the rise of one-fifth of the current largest 300 US public companies and that three-quarters of the largest US VC-backed companies would not have existed or achieved their current scale without an active VC industry.

Whither AgTech?

Sarah Nolet wrote a very thoughtful essay “Is Agtech Broken for Venture Capital—or Are We Asking the Wrong Question?” , where she tried to diagnose some of the issues with venture capital and AgTech. Her essay had been brewing in my mind for some time.

When things don’t go as expected, we always look to find a scapegoat. There is no easier scapegoat to find than the “clueless VCs in Silicon Valley” for all the troubles of AgTech.

The “Silicon Valley VCs” have become the you-know-who’s of AgTech.

Many folks make statements, which are reminiscent of the Main Street vs. Wall Street debate and use Salinas Valley as the analog for Main Street. Salinas Valley (which is the salad bowl of the United States) represents farmers and farming communities.

Silicon Valley is a caricature of the “clueless VCs” from their fancy offices in the Silicon Valley and who push certain agendas which are at odds with how agriculture works.

As usual, the world is more complicated than simple binary narratives.

I mean, if you want simple binary narratives, which are not based in facts, you can just go listen to the All-In podcast, though fortunately they do not cover Agrifoodtech.

In order to get to the bottom of this question (and I am still working on it), I decided to go and talk to some VCs (regular and corporate VCs), quite a few entrepreneurs, experienced strategic agribusiness employees, and other experts to get their opinions.

While many people agree that venture capital is not the right fit for many problems in AgTech (and this is true outside AgTech as well), there are many reasons why it might be the case, and why AgTech has struggled to find adoption and scale.

In today’s edition, I will try to synthesize what I have learnt.

Us vs. Them attitude

VCs who come from outside of AgTech say, sector VCs don’t understand how to scale these companies, whereas people from the industry say, people from outside AgTech do not understand how to fund and scale AgTech companies.

The evidence is quite to the contrary. If you take a look at startups which have gotten an exit or seem to be doing well, have often received funding from a mix of sector and non-sector VCs.

For example, Blue River received funding from Pontifax Global Food and Agriculture Technology Fund, agribusiness corporate venture arms Syngenta Ventures and Monsanto Growth Ventures, Khosla Ventures, Data Collective Venture Capital, and Eric Schmidt’s Innovation Endeavors.

You could go and look at example after example, and you will find many where companies have received VC dollars from multiple within sector and outside sector investors, including family offices, and high net worth individuals.

This is not a very satisfying trope to hang one’s analysis on.

Misaligned timelines

Agriculture moves at a certain natural pace dictated by the physical world timelines of how plants grow. The typical time for a startup to bring a new product to market and scale is fairly long in agriculture, and it creates timeline misalignments with VC horizons. Multiple people made this point.

For example, Michael Stern, ex-CEO of the Climate Corporation said,

So while I still believe venture capital is the right funding model for AgTech, the key is having the right time horizon. That also means not every VC firm is suited to invest in this space. I have yet to see an AgTech startup that hasn’t faced significant challenges along the way.

And then there’s the adoption curve. Farmers are independent business owners managing risk. If they plant 1,000 acres, they’re not going to test a brand-new tool across their entire operation in year one. Maybe they’ll try it on 10% of their land. If the results are good, they might scale up to 25% the next year. But if the results are just marginal—or if they have an off year due to external factors—they may decide to sit on the sidelines for a season and wait until they see stronger proof. This makes AgTech adoption a much longer and more variable process than other industries.

So yes, I believe venture capital is the right approach, but it requires investors who understand the unique challenges of AgTech and are willing to be patient. When there’s a mismatch between VC expectations and the realities of the agricultural cycle, it creates real problems.

Shubhang Shankar, Managing Director for Syngenta Group Ventures said something similar,

What I think the last few years have shown us is that there’s no one-size-fits-all solution for agriculture. You can’t apply pure venture capital to every fundamental issue in this space and expect it to work. That’s how I’d describe the arc between those two articles.

So in my view, the core problem in that sector was a mismatch between the timeline needed to develop the technology and the timeline venture capital typically works on. I’ve attended a few events by the Good Food Institute in Israel, and they’ve made a similar point.

There are many such examples, segments where venture capital isn’t a good fit, and people are realizing that over time. And it really comes down to the timeline. That said, I’m a big believer in venture capital. We absolutely need high-risk capital to get speculative businesses off the ground. We need an asset class that’s comfortable with a high failure rate. Without that, the world would be a poorer place. And I think agriculture needs it too.

Venture capital needs to start the job. It does not need to finish it. I think that’s a really important distinction. VCs can take these innovations to the point where they either become self-sustaining or where another, more patient asset class can step in and take over.

Tracey Wiedmeyer, CEO of Gripp and an entrepreneur had to say the following,

I deeply value investors with patience—those who understand that Ag moves at its own pace. AgTech attracts outside investors because they see a massive market and get excited by hockey-stick pitches—but without understanding Ag’s complexities, many won’t come back after one bad experience.

Mark Brooks, ex-VC at FMC Ventures said something similar,

In this new era, we face issues like labor shortages, pest resistance, and supply chain disruptions, among many others. When you factor in the venture capital model, the disconnect becomes clear. VC funds typically operate on a 10-year cycle, give or take. Investors deploy capital over three to four years, then spend the next six to seven years managing follow-ons, securing exits, and harvesting returns. After 10 to 12 years, the fund winds down, and a new one begins.

That model works exceptionally well in software, where rapid iteration, high margins, and quick exits drive success. But ag operates differently. We’re not just dealing with software—we’re working with molecules, plants, growing cycles, and farmers who may only get 40 or 50 growing seasons in their lifetime. Adoption moves at a fundamentally different pace, not to mention the regulatory hurdles we discussed earlier.

Because of this, the traditional VC cycle doesn’t align perfectly with ag and food innovation. That’s not to say it doesn’t work—it can and does. But we need to acknowledge the misalignment and adjust accordingly. The reality is simple: these sectors need innovation. Without it, progress stalls, and we fail to contribute to a more sustainable planet.

Thin and fragmented markets

Agriculture does have the challenge of fragmented and thin markets. There are 1000 different problems to solve, and each of them need a slightly different solution. Mikalya Mooney broke down this problem really well.

The issue is that ag isn’t one market—it’s thousands. It’s fragmented by crop, region, soil type, climate, and even personal preference. So a robotics company might build an amazing apple harvester—but that tech won’t work for corn, soybeans, or lettuce.

What looks like a huge market on paper is small in practice.

Let’s say your startup solves labor with a machine that replaces field crews. Huge problem and absolutely worth solving. But the machine only works on high-density orchard crops. Suddenly, you’re serving 2% of U.S. farms. That 2% might love you, but the market isn’t scalable in a traditional venture sense. The TAM was theoretical.

These companies and solutions are critical but niche. They can grow into solid $20M-$50M in revenue companies with real impact —but they don’t hit the $1B mark traditional VCs are looking for and betting on.

I had written extensively about the thinness of agriculture markets, which poses unique challenges for startups to scale, with limited options on exits through incumbents.

There are also very few buyers and sellers when it comes to AgTech solutions. When you think about the massive commodity row crop market in the US, there are less than 200K farmers who account for the majority of the acres. The thinness of the market makes price discovery difficult, and there is not a large enough pool of potential customers to drive down your costs to make your unit economics work.

Access to distribution is a challenge

Due to the concentrated nature of the agriculture industry, be it equipment, seed, chemicals, offtake, etc. incumbents have a stranglehold on distribution. For a startup to reach customers, it has very few options.

Either use very expensive and time-consuming direct to grower models for distribution, or try to partner with an existing incumbent or get them on your cap table to get access to distribution.

More startups have died due to access to distribution, vs. not have a good product. Farmwise is a recent example, which in spite of having a good product, struggled to find distribution and ultimately its assets were acquired by Taylor Farms.

The classic example is FBN. When they tried to go direct to farmers with their input products, their business model was hobbled due to the lack of access to efficient distribution channels.

Specialized applications which do not translate

Given the fragmented nature of problems, even if your startup is able to solve a problem in a given context, unless it can “turn the crank” (as said by Mark Brooks), it cannot scale its business, which becomes interesting for a VC level growth.

A startup that can “turn the crank” and generate new monetizable assets consistently holds far more value for a venture investor. That’s what makes a company truly scalable and investable. There’s nothing wrong with single-product startups, but from a VC perspective, that broader capability is a key factor that often gets overlooked.

Mark Brooks talks about robotic solutions,

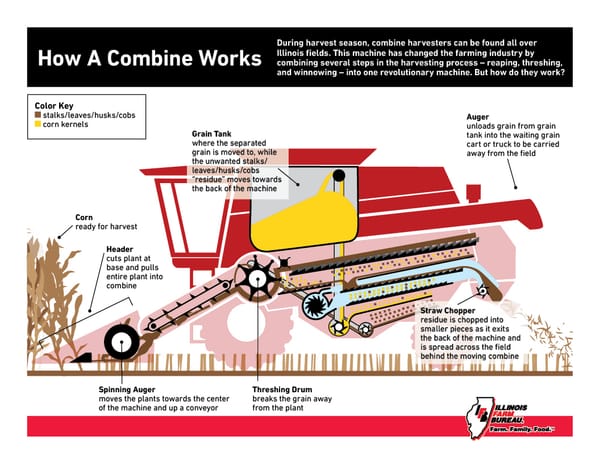

Robotic solutions in agriculture generally require significant capital expenditures. Developing the hardware and underlying technology costs a lot of money, making it a high-capex endeavor. When considering the market size, it’s easy to see a massive opportunity—there are billions of acres of farmland worldwide, and every farmer needs solutions for planting, harvesting, seeding, spraying, and more.

But the real question is: how many growers and how many acres can actually adopt a given robotic solution? That depends on factors like machine size, speed, cost, and overall feasibility. Suddenly, what seemed like an enormous market shrinks into a much narrower one, depending on the specific technology. Combine that with high capex requirements, and the traditional VC model no longer fits as cleanly.

There are many startups which have died because they could not turn the crank fast enough or efficiently. I had written about Advanced Farm and their apple picking capability, which could not translate to other crop types without a massive amount of incremental investment.

The company I worked at (Mineral) faced the same problem of not being able to “turn the crank” fast enough and to be able to find distribution.

Final thoughts

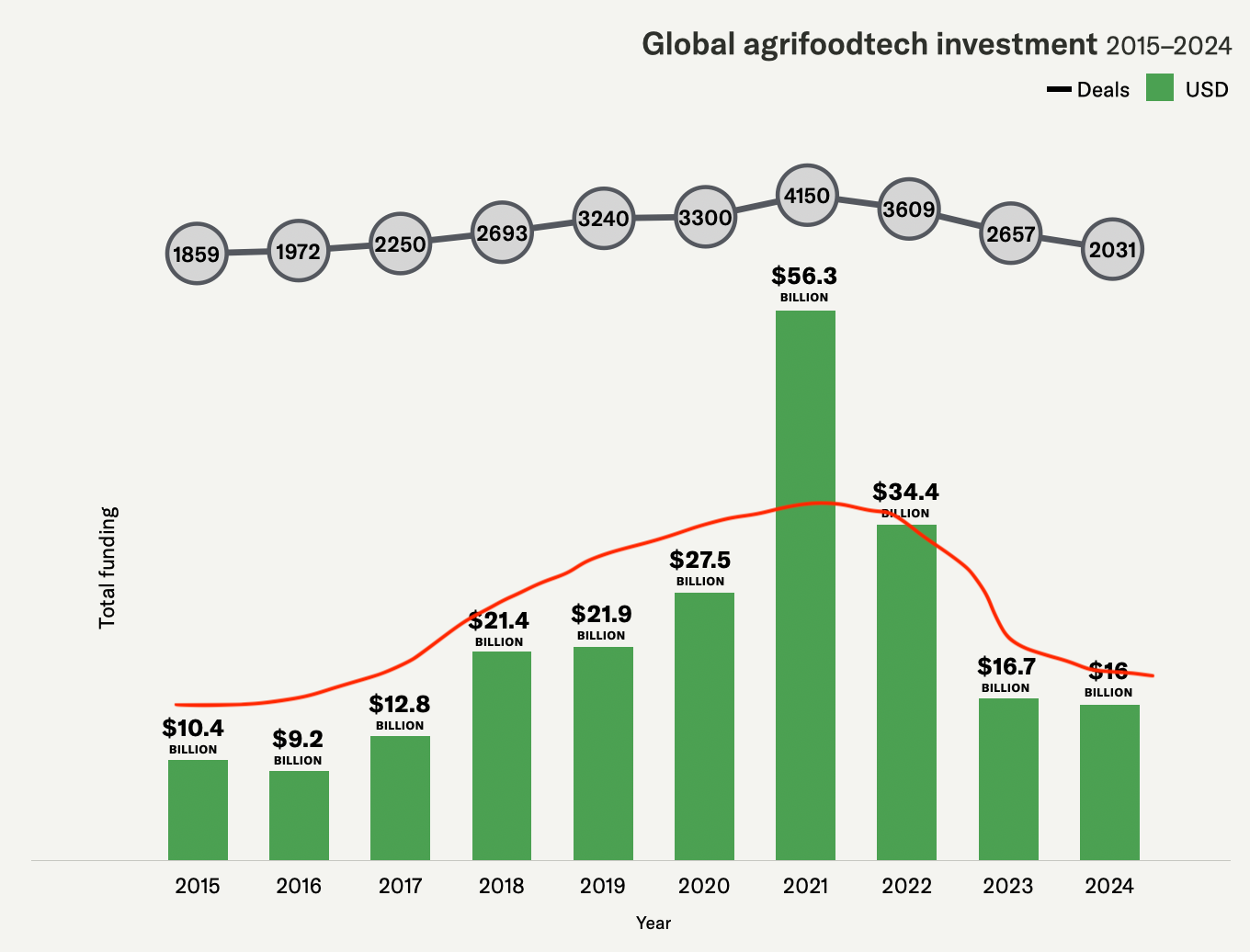

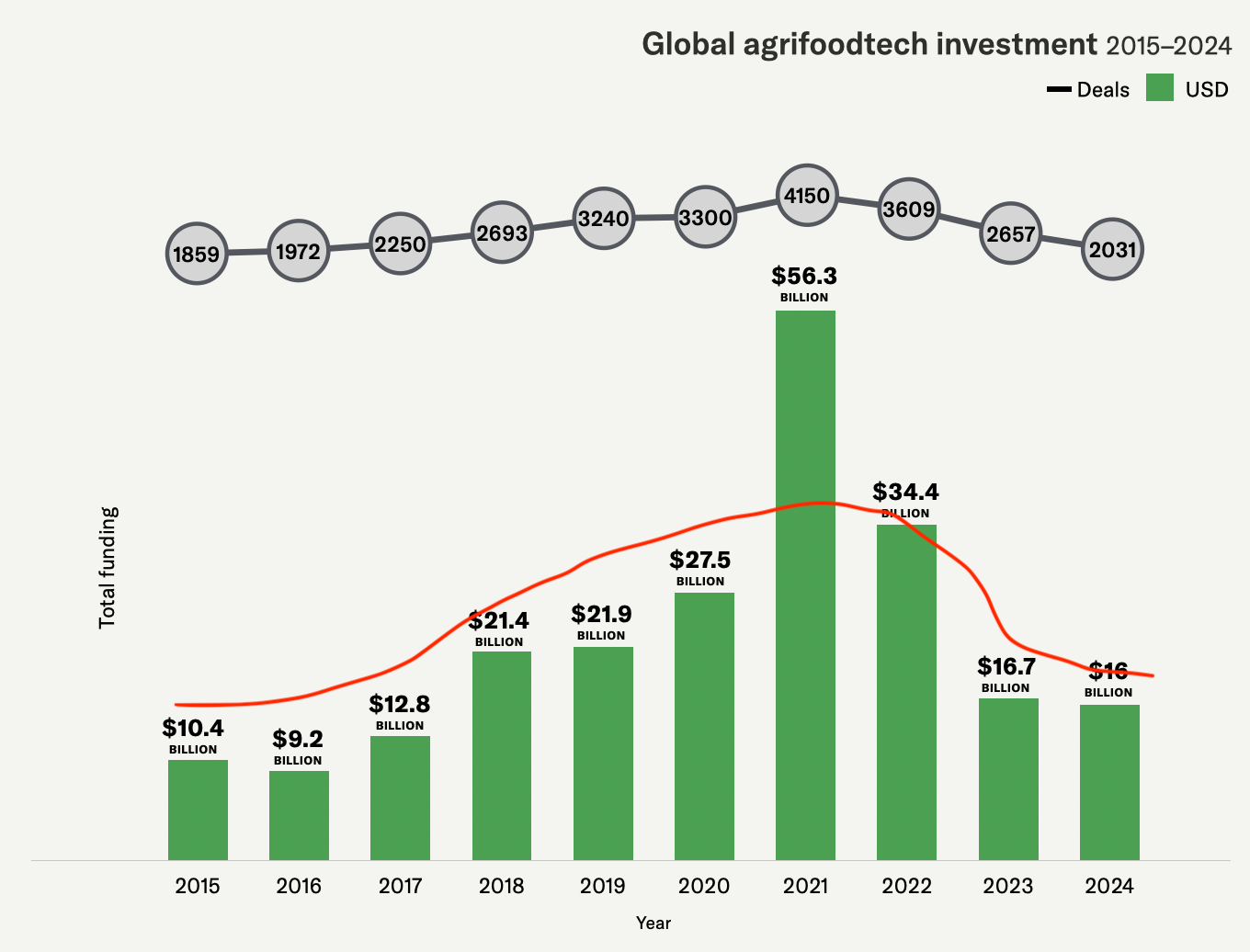

While a huge amount of ink has been spilled about the demise of AgTech, (and some or a large amount of it is justified), we also have to keep in perspective that 2021 was an anomaly in terms of the level of investment across the board, including AgTech.

Maybe the red line was supposed to be the natural curve of Agrifoodtech investment, and 2021 was an anomaly. Don’t get me wrong, a 50% drop between 2022 and 2024 is not something not to worry about, but it is not as bad, if we see 2021 as an outlier, instead of 2023 and 2024 as outliers. (Image source: AgFunder News)

So what should startups and VCs do to increase the chances of success for the ecosystem?

- Align timelines and find a mix between sector specific and non-sector specific investors

- Find different funding mechanisms with different incentives, and try to also align based on the stage of your business

- Try to get strategic investors on your cap table, if it makes sense

- Work with existing agribusiness incumbents to tap into distribution channels

- Figure out if you can “turn the crank” to continue to scale your business, without having to scale your costs significantly

- If you are not in a position to “turn the crank” fast enough,

- De-risking mechanisms for startups and investors (venture studio, test farms, partnerships)

Ultimately the best option for a startup is to not take VC money. If they can fund themselves and scale with non-dilutive capital, or even better though revenue, there is no better option. And this is true for any startup in any sector!

I will leave you with an example of one of my favorite companies right now called Boom Aerospace, which is working on making commercial super-sonic flights possible.

They have been battling through problems of supersonic flights, physics problems with sonic booms, rethinking aircraft design, fuel requirements, regulation, economic unit costs, customer acceptance and much more.

They were founded in 2014 and they have done a few test flights in the last 11 years.

They are funded by a group which includes VCs and many high net worth individuals. Bessemer Venture Partners, Y combinator, Alex Gerko, Michael Moritz, Paul Graham, Reid Hoffman, Sam Altman, Emerson Collective, American Express. They have received advanced orders from a few major airlines, assuming they can hit certain milestones.

How should a Boom Aerospace type company (if it exists) in AgTech be funded?