The strategic role of Corporate VC in Agriculture

SFTW Convo with Mark Brooks, ex-CVC at FMC

Welcome to another edition of SFTW Convos!

This week’s conversation features Mark Brooks, ex-Managing Director of FMC’s Corporate Venture Capital arm. I had the privilege to sit down with him and have a conversation about his experience being an entrepreneur, and a corporate VC.

Mark is one of the few CVCs with experience in multiple industries (accounting and agritech), and multiple CVC funds (Syngenta and FMC).

Given the current funding and investment situation in Agrifood, this is a good conversation to read through for entrepreneurs, investors, and agribusinesses.

Summary of the Conversation

In this conversation, Mark Brooks shares his unique journey from climate science to corporate venture capital in agriculture. He discusses the evolution of corporate venture capital (CVC) in the ag industry, the characteristics that drive corporations to establish CVC entities, and the challenges they face in navigating innovation.

Mark emphasizes the importance of strategic thinking in CVC investments, the need for innovation in agriculture, and the misalignment of traditional VC models with the realities of ag-tech.

He also explores various funding models and the considerations for investing in ag-tech innovations. In this conversation, Mark Brooks discusses the dynamics of corporate venture capital in the agricultural technology sector, emphasizing the importance of partnerships between startups and major corporations.

He highlights the challenges faced by AgTech investors, the role of non-AgTech investors, and offers advice for entrepreneurs looking to innovate in this space. The discussion also explores the future of agriculture, including the impact of artificial intelligence and the need for broader thinking about the role of agriculture in various industries.

Mark Brooks (ex-VC at FMC) (Artwork by EI). Original picture provided by Mark Brooks

Mark Brooks background

Rhishi Pethe (RP): Let's give our readers a little taste of your background and how you came to your last role of being a corporate VC at FMC.

Mark Brooks (MB): My background has taken some curvy turns, and to some extent, I’m still figuring out what I want to do when I grow up. I started my career as a climate scientist after studying meteorology at university. Upon graduation, I spent about 10 years at North Carolina State University in a non-teaching role, conducting research on weather and climate at their intersection with agriculture, energy, transportation, and various other industries.

After a decade in academia, I realized I didn’t enjoy it. Writing grants, proposals, and peer-reviewed papers didn’t appeal to me. Instead, I felt drawn to building and creating—turning science into something practical and useful for people. So, I left.

I launched an AgTech company with a co-founder before AgTech had even become a defined category. We built a decision support platform for specialty crop growers in the U.S., helping them manage risks from weather events.

Through that experience, I learned a lot about entrepreneurship and AgTech. When I tried raising money from venture capitalists, nobody cared—AgTech wasn’t even on their radar. Without funding, we couldn’t scale, so I pivoted into corporate strategy.

That path led me to the AICPA, known as CIMA in the UK—the world’s largest association for accounting professionals. I like to think of it as the Vatican for finance and accounting. There, I led corporate strategy and innovation, designing, architecting, and launching a corporate venture program focused on pre-seed and seed-stage startups that were reshaping the future of accounting and finance. Over three or four years, I led investments in about a dozen companies.

But I wanted to return to science and agriculture—my roots. That’s when I found an incredible opportunity at Syngenta Ventures, where I joined the team as an investor. Over the next few years, I made several investments and sat on the boards of multiple companies.

Then, I got a call about an incredible opportunity to lead FMC Ventures. Running a corporate venture capital group had always been a goal of mine—driving innovation by allocating capital where it matters. This role has been an absolute blast, easily the best job I’ve ever had.

What is the need for Corporate Venture Capital?

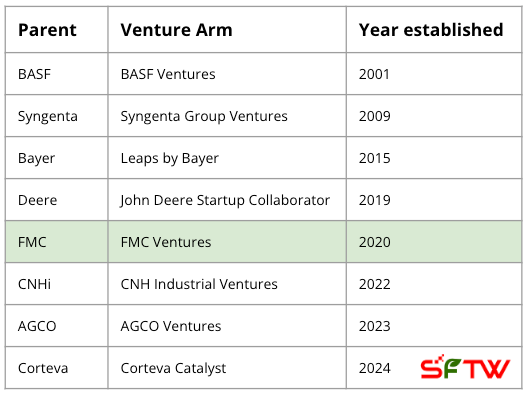

RP: You moved from science to accounting—widely stereotyped as the most boring field—and yet, you set up a corporate venture fund there. I looked into which agricultural companies have established corporate VC funds, and only a handful have done so.

What factors drive a corporation to decide, we need to launch a corporate VC entity?

MB: What I’m about to say applies not just to ag and food but to many science-heavy industries: large corporations excel at their core competencies. They employ world-class R&D teams, top-tier marketing professionals, and highly skilled on-the-ground experts to strengthen that core.

However, when we examine where true innovation and game-changing breakthroughs originate—not just in ag but across various industries—we consistently see them emerging from startups, entrepreneurs, and pattern breakers.

Comparing today’s Fortune 500 list to those from 20, 30, or 40 years ago reveals a completely different lineup. The same holds true for the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Index. These lists evolve because small, scrappy companies discover new ways to create value, develop better technologies, or introduce more compelling value propositions. Over time, they chip away at incumbents and redefine industries.

For large corporations looking to launch a CVC program, this realization often serves as the catalyst: they must tap into the startup ecosystem in a way that fosters meaningful collaboration and aligns incentives.

The most effective CVCs extend the halo effect of their corporate parent to these startups. They provide more than just capital—they bring access to marketing expertise, distribution channels, R&D capabilities, regulatory knowledge, and an established market footprint. For startups eager to enter the industry, this access proves invaluable.

When managed well, these partnerships also benefit corporations, granting them early exposure to disruptive innovations that can reshape their core business or redefine their category.

RP: When you look at the history of corporate VCs, the timeline tells a different story. FMC started its fund about five years ago, and Syngenta has been at it for 10 to 15 years. Meanwhile, the broader VC industry has existed for 50 years.

So why the big lag? If what you’re saying is true, why didn’t more of these big corporations embrace corporate VC earlier? What took them so long?

Founding years for Corporate VC (or similar entities) in Agriculture

MB: The venture capital industry began 50 or 60 years ago, primarily focusing on software companies. These businesses could iterate rapidly, scale quickly, and achieve high-value exits within a relatively short timeframe. That’s where VC firms thrived and found the most success. In contrast, corporate venture capital (CVC) is still a relatively new function across industries, not just in ag.

Fifteen or twenty years ago, very few corporate venture teams existed. While I don’t have the exact numbers in front of me, I can say with confidence that the landscape looked vastly different.

Today, corporate venture participation has surged. PitchBook regularly publishes reports tracking venture deals that involve CVCs, and the trend shows a steady increase. Currently, nearly half—or even more than half—of all VC deals or capital deployed involves a corporate investor.

The slow adoption of CVC programs stems from several factors. First, companies have struggled to manage it effectively because it’s a new function. Many boards and management teams lack a clear framework for governance.

Second, CVC professionals require a rare skill set—they must navigate corporate bureaucracy and politics while maintaining an entrepreneurial mindset to source strong deal flow. That combination is difficult to find.

Finally, CVC involves risk capital, which many publicly traded corporations hesitate to allocate. Traditional venture funds operate under the power law—most investments will fail, but a single big win can drive returns. Accepting that reality is difficult for many corporate leaders, especially those operating under a quarter-to-quarter financial mindset. That hesitation has slowed adoption, but as CVC participation continues to rise, companies are beginning to recognize its strategic value.

RP: If you look at the S&P 500 or any list of top companies, it constantly changes because new players emerge and disrupt incumbents. But in the ag industry, that pattern doesn’t seem to apply the same way.

John Deere has been around for more than 100 years. FMC—while I don’t know the exact dates—has also existed for over a century. They’ve changed names, merged, and restructured, but if you trace their history, they’ve endured. The same goes for BASF, Syngenta, and others. These companies have managed to stay relevant and avoid disruption for over a century.

So where does this fear of disruption come from? Why do they now feel the need to invest in corporate VC funds to avoid being displaced?

MB: The big agriculture incumbents have dominated the industry for a long time. But here’s the deal—when you examine the pace of innovation in data analytics and artificial intelligence and compare it to the industry’s challenges—carbon emissions, greenhouse gases, labor shortages for growers, and resistance to traditional chemistries that have been on the market for decades—you start to see a shift. At the same time, research and development outside of corporate giants continue to accelerate, creating what I’d call an opportunity storm.

Today, major corporations no longer attract the best and brightest minds, nor do they control the most cutting-edge innovations and technologies. That dynamic may have existed 50 years ago, but I’d argue it no longer holds true. Instead of viewing this as outright disruption, it might be more accurate to see it as the natural evolution of a capitalist economy—where companies that fail to innovate inevitably decline.

VC and CVC funding model fit

RP: I want to explore—different funding models, with CVC being one of them.

Could you break down where the CVC funding model works well in Ag and where it doesn’t? How do you determine which companies, problems, or trends make sense for a corporate venture capital group to invest in—and which ones don’t?

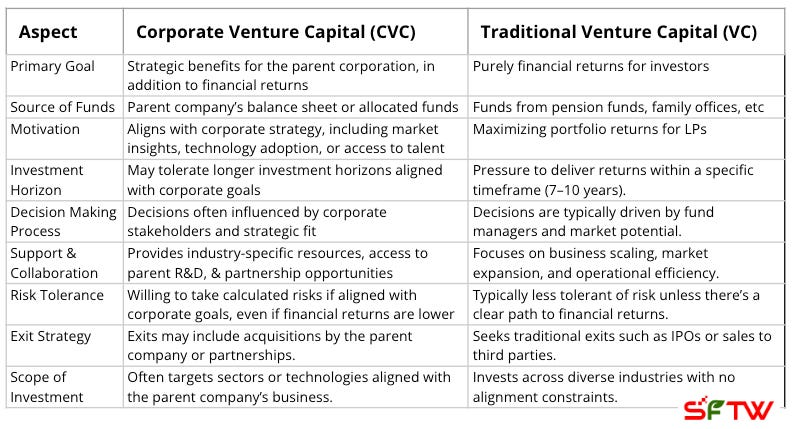

MB: That’s a good question. A corporate venture capital (CVC) group operates with a different mindset than a traditional financial VC fund. While both assess financial returns, a CVC also prioritizes strategic value—that’s its real special sauce. Beyond capital, a CVC brings a halo effect, offering non-tangible resources that can significantly benefit portfolio companies.

From an entrepreneur’s perspective, having a corporate investor on the cap table can be a powerful advantage. It provides direct visibility into specific areas of the corporation’s business and aligns incentives on both sides. Since the corporate has a stake in the startup, it has a built-in motivation to collaborate, and the startup gains an incentive to engage deeply with the corporate. When both parties embrace this dynamic, it creates a win-win-win—a win for the corporation, a win for the startup, and a win for the broader AgTech ecosystem.

RP: That makes sense. I want to follow up on that—does CVC play a more critical role in industries like Ag, where heavy regulation and market concentration shape the landscape?

In Ag, just a few major players dominate key sectors—four agrochemical companies, four seed companies, and four equipment manufacturers control 50 to 60% of the market. For a startup, accessing distribution without a strategic partnership is incredibly difficult and expensive. Building out a distribution network from scratch isn’t always feasible, which makes partnerships with established corporations a major advantage.

On the chemical and seed side, regulatory hurdles add another layer of complexity. For startups, navigating those processes is not only difficult but also prohibitively expensive.

Does this dynamic make corporate VC more important in Ag compared to less regulated industries, where distribution isn’t as tightly controlled by a handful of major players?

MB: I’m not sure I agree with that, but I reserve the right to change my mind. I see the opportunity differently. Instead of focusing on industry consolidation or regulatory challenges, I’d frame it around the massive global problems that innovation in ag, food, and adjacent sectors can solve. These industries hold the potential for the trillion-dollar opportunities of our lifetime—whether in food, energy, biotech, or related fields.

If existing corporations want to shape that future and drive meaningful change, and if their shareholders want to benefit from it, then a CVC program becomes an incredibly powerful tool.

Across industries, not just in ag and food, CVCs stand out as one of the few mechanisms corporations can use to tap into the startup ecosystem. They allow companies to discover new solutions to existing problems, identify emerging challenges, and accelerate innovation in ways traditional R&D often cannot.

Ultimately, making a real impact on the future of our planet requires visionary leadership—people willing to embrace these opportunities and act on them. This sector is uniquely positioned to drive that change.

RP: You already mentioned that traditional VCs prioritize financial returns, while corporate VCs balance financial and strategic goals. You also touched on factors like distribution challenges and longer timelines. There’s an ongoing debate—both online and in industry circles—that the traditional VC model doesn’t work well for certain parts of AgTech.

Differences between CVC and traditional VC

What are your thoughts on that? I find it hard to believe that the entire VC model is a poor fit for AgTech. Maybe we need to be more precise with these statements—rather than saying VC doesn’t work for AgTech, should we instead define which specific types of problems or business models it doesn’t work for, and which ones it does?

I’d love for you to go a couple of layers deeper on this and break it down beyond just the broad claim that VC isn’t a good fit for AgTech.

MB: Over the past 50 years, innovation in ag and food has primarily focused on delivering calories and preventing starvation. That was crucial, but we’ve moved beyond that phase. Now, we’re entering a new era—one centered on nutrition, healthy outcomes, and planetary resilience. The challenges we need to solve today differ from those of the calorie-delivery era.

In this new era, we face issues like labor shortages, pest resistance, and supply chain disruptions, among many others. When you factor in the venture capital model, the disconnect becomes clear. VC funds typically operate on a 10-year cycle, give or take. Investors deploy capital over three to four years, then spend the next six to seven years managing follow-ons, securing exits, and harvesting returns. After 10 to 12 years, the fund winds down, and a new one begins.

That model works exceptionally well in software, where rapid iteration, high margins, and quick exits drive success. But ag operates differently. We’re not just dealing with software—we’re working with molecules, plants, growing cycles, and farmers who may only get 40 or 50 growing seasons in their lifetime. Adoption moves at a fundamentally different pace, not to mention the regulatory hurdles we discussed earlier.

Because of this, the traditional VC cycle doesn’t align perfectly with ag and food innovation. That’s not to say it doesn’t work—it can and does. But we need to acknowledge the misalignment and adjust accordingly. The reality is simple: these sectors need innovation. Without it, progress stalls, and we fail to contribute to a more sustainable planet.

Risk capital plays a critical role in fueling that innovation, yet few sources exist for it in ag. Venture capital remains one viable approach, but we need to explore other models. Right now, investors, entrepreneurs, and capital allocators must think more creatively about how we fund innovation. We also need to rethink and recalibrate how we measure returns in this space.

I’m not saying the VC model is broken. It has funded incredible companies and produced meaningful advancements. But if we look closely, we see cracks in the system—cracks we have the opportunity to fix.

RP: Let’s go one level deeper. You mentioned the misalignment between the VC model and how innovation develops and scales in Ag. But innovation is a broad term, so let’s break it down with specific examples.

Take three different types of AgTech innovation:

- Farm Management Software – This is a software-driven business model, fundamentally different from other forms of Ag innovation.

- New Herbicide Development – This involves creating a novel molecule, requiring extensive R&D and regulatory approvals.

- Automation in Specialty Crop Harvesting – This focuses on robotics and mechanization to replace labor-intensive tasks.

Could we walk through each of these examples and analyze what makes them a good fit—or a poor fit—for venture capital versus corporate VC? I know these are high-level categories, and there are nuances within each, but what key factors would you look at in each case to determine whether VC funding, corporate VC, or another model makes the most sense?

MB: Well, I don't think it's a categorical yes or no. I'll share the considerations with the root of how traditional VC was designed and works.

Robotic solutions in agriculture generally require significant capital expenditures. Developing the hardware and underlying technology costs a lot of money, making it a high-capex endeavor. When considering the market size, it’s easy to see a massive opportunity—there are billions of acres of farmland worldwide, and every farmer needs solutions for planting, harvesting, seeding, spraying, and more.

But the real question is: how many growers and how many acres can actually adopt a given robotic solution? That depends on factors like machine size, speed, cost, and overall feasibility. Suddenly, what seemed like an enormous market shrinks into a much narrower one, depending on the specific technology. Combine that with high capex requirements, and the traditional VC model no longer fits as cleanly.

So, how do we fund these innovations? I don’t have the perfect answer, but there are many creative ways to approach it. One option is blended finance, combining non-dilutive grants—such as government-sponsored programs—with venture funding. These grants help mitigate risk for VCs.

Another option is debt financing, where investors put debt into the company, taking priority in the capital stack while earning interest as the company scales. Revenue-sharing models also offer potential—investors could receive a percentage of revenue as commercialization progresses.

There are plenty of ways to structure financing, but the key considerations remain market size, capex, and the time required to bring these technologies to market.

VC vs. CVC

RP: I get that I’m asking an almost impossible question to answer, but I’m really trying to unpack the key considerations. You mentioned factors like capex, market size, and the applicability of a given technology.

Looking at the second example—biologicals and new crop protection solutions—FMC has invested in companies like Agrospheres and Micropep Technologies.

If I’m a VC or a CVC evaluating an investment in this space, how should I approach it? What specific considerations should I focus on? How do the decision-making criteria differ between traditional venture capital and corporate venture capital in this context?

MB: If I’m a traditional financial VC evaluating a biologicals company, I want to see a strategic investor involved. That signals a potential exit pathway—if strategics are paying attention and investing, they clearly see value in the startup’s capabilities. For me as a VC, that serves as a major validator.

Beyond that, I also consider the timeline for bringing the product to market and the intellectual property protections around it. Take the examples of Micropep, Agrospheres, and the acquisition we did at FMC Ventures—three great companies that I have strong conviction in.

But as a VC, I have to ask: how long will it take to navigate regulatory trials, greenhouse trials, and the approval processes required in different regions? These steps take years, cost a fortune, and generate no revenue while in progress. That creates significant risk compared to software startups that can iterate and scale quickly.

Another critical factor is a company's underlying capability. Many biologicals startups have one or two active ingredients or molecules that show promise, but nothing beyond that. While these companies can be attractive for acquisitions, licensing deals, or commercial agreements, they aren’t necessarily venture-backable.

To be a strong VC candidate, a company needs a scalable platform—something that functions like a machine, continuously producing new active ingredients that can be sold, licensed, or monetized.

A startup that can “turn the crank” and generate new monetizable assets consistently holds far more value for a venture investor. That’s what makes a company truly scalable and investable. There’s nothing wrong with single-product startups, but from a VC perspective, that broader capability is a key factor that often gets overlooked.

RP: Would that consideration be also important if you are a CVC at FMC or Syngenta?

MB: Yes, I’d say yes, because the major corporations care about many things, but one of their biggest priorities is maintaining a pipeline of proprietary, premium molecules to launch into the market. They can acquire startups that have developed one or two promising molecules, but they can also invest in platform companies capable of consistently producing more in a targeted way.

That scalability holds tremendous value for corporates. And because it creates a flywheel effect—where the corporates benefit from a steady stream of new innovations—it also increases value for venture investors.

RP: If one company is a one- or two-trick pony and another has the ability to, as you put it, turn the crank and continuously produce new innovations, how does a corporate approach them differently?

Would a corporate prefer to form a partnership or a commercial agreement with the single-product company while opting to invest in the scalable platform company?

And if a corporate does invest, what should the entrepreneur expect on the other side? Does that investment eventually lead to an acquisition, or should they be thinking about a different kind of outcome? I know that’s a multi-part question, but I’d love to hear your take on it.

MB: That’s a great question. Entrepreneurs working with corporates primarily seek capital, which validates their work and funds their business. But beyond funding, they look for market access, distribution channels, and joint business opportunities that can accelerate growth.

Entrepreneurs also benefit significantly from R&D support, formulation expertise, and scientific insights that improve their product’s stability and performance in real-world environments. Major corporations excel in these areas and can provide startups with critical technical support.

Additionally, corporates offer regulatory assistance—when it’s time to submit dossiers for approval across different regions, strategics have large, specialized teams to handle the process. They also have connections to lobbyists and advisors, resources that a startup typically lacks.

For startups in the biological space, working with a corporate investor and collaborator can be game-changing. However, there’s also a downside. If the corporate loses interest, deprioritizes the innovation, or decides the startup isn’t delivering the expected impact, the partnership can become a drag. That’s a real risk, and startups need to be aware of it and prepared to navigate those challenges.

RP: There was some discussion online a few weeks ago about what makes AgTech companies successful—though, of course, success is subjective. Some have argued that companies like AgVend — though not in biologicals but more in the software/hardware space—along with Climate Corp (which had its big moment 10–15 years ago), didn’t take investment from traditional AgTech VCs. Instead, they sought funding from outside investors.

Some people claim that’s precisely why they succeeded. I’m not sure how to interpret that argument, but do you have any thoughts or reactions to it?

MB: Success depends on how you define it. If raising money is the metric, then sure, these startups are successful. But if success means building thriving businesses with strong EBITDA and high exit valuations, that remains to be seen.

That said, having non-AgTech investors in the AgTech space brings significant value. They offer fresh perspectives and ask different kinds of questions, which can be incredibly valuable for boards and management teams. In sectors like software, robotics, or FinTech applied to agriculture, non-Ag investors also signal a broader range of potential exit opportunities—something that benefits both startups and the ecosystem as a whole.

It’s also important to recognize that the AgTech VC market remains small and, in fact, appears to be shrinking. Fewer pure-play AgTech VC funds exist today than in the past. Given that reality, entrepreneurs should not abandon the AgTech VC ecosystem, but they would be wise to explore adjacent investment opportunities as well.

RP: How do we make sense of this? On one hand, we talk about trillion-dollar opportunities in food and ag. In a market-driven economy, capital should naturally flow toward those opportunities.

But if that’s the case, why are VC investors pulling back from the sector? Why is AgTech VC shrinking?

MB: That question has a simple answer: the return timelines don’t fit the traditional 10-year VC cycle. AgTech exits, aside from Climate Corp and a handful of others, typically fall below $100 million. A few might break past that threshold, but overall, enterprise values remain small.

VC funds exist to return capital to their limited partners. So if an investor must choose between AgTech—where they can drive planetary impact but face weak returns—or another sector with higher returns and shorter timelines, they’ll follow the money. It’s an opportunity cost decision. Why invest $100 million in AgTech when another sector offers a better potential payout?

Maybe the real question we should be asking is: how do we turn food and ag into true trillion-dollar opportunities while accounting for the known challenges—long timeframes and limited exit potential? That’s where the conversation needs to go.

RP: Automation is a broad category, but there’s clearly something there. The challenge, though, is exactly what you described. Take harvest automation—if I build a system that can harvest strawberries, that doesn’t mean it can harvest apples. Each crop presents unique challenges.

Maybe that’s the leap of faith investors have to take. If a company can automate harvesting for one specialty crop, can they turn the crank and quickly scale the technology to 50 or 100 different crops worldwide? If so, that transforms the opportunity into something much bigger.

Biologicals are another interesting case. Their effectiveness depends so much on context—soil, climate, crop diversity—that scaling isn’t straightforward. Is there a breakthrough that allows a company to say, It works here, tweak it slightly, and now it works there too? That kind of repeatable process would be a game-changer.

Even if we don’t have the answer, what are the right questions to ask? What has to be true for this to work?

We may not know for sure, but we can define the key assumptions that would need to hold for this to become a billion-dollar—forget trillion—let’s say a $10 billion opportunity. What conditions must exist to attract serious investment and drive real scale?

MB: Let me get this thought out before I forget it. One major change needs to happen to unlock billion-dollar opportunities in AgTech: a significant market event.

Right now, Bayer, Syngenta, Corteva, FMC, BASF, and UPL dominate the industry. These companies have been around forever and control the distribution channels with an almost oligopolistic grip. That dynamic needs to shift.

I think we need a major market event—maybe one of these giants goes out of business, or a massive consolidation reshapes the industry. Something has to happen that creates room for high-potential startups to scale rapidly or merge to gain market strength.

If that kind of shake-up occurs, it could trigger a wave of opportunity beneath the surface, allowing innovation to flourish. But I need to think more about this. I’ll come back to you with deeper thoughts.

Startup considerations

RP: You’ve been on both sides of the table—you struggled to raise funding as an entrepreneur, and later, you worked as a corporate VC at two different companies.

What advice would you give to someone starting a company in this space today? Who should they work with?

Obviously, it depends on the product, but should founders try to bring more than one corporate VC onto their cap table if possible? As you pointed out, a corporate investor might later decide to exit the space or shift priorities, leaving the startup vulnerable. That can be difficult to manage, but what should entrepreneurs consider when navigating these relationships?

If I’m an entrepreneur launching a company right now, what key things should I focus on?

MB: I’ll start with the obvious advice and then move to the less obvious.

First, find a problem you’re truly passionate about—something big, something that excites you to solve. That’s foundational. But beyond that, I encourage entrepreneurs in this space to think beyond just one problem. Instead, look at a chain of problems.

Consider the food and ag value chain. It starts with the grower, moves downstream, and passes through multiple steps, all interconnected. The most valuable companies of the future won’t just develop a new molecule or a piece of robotic equipment—they’ll build business models that solve problems for multiple stakeholders across that value chain. For example, a startup might create a financial solution for growers while simultaneously improving visibility for downstream buyers.

Right now, I don’t see enough of that approach in AgTech. Entrepreneurs need to focus on business model innovation just as much—if not more—than on the technology itself.

Another key piece of advice: take a transdisciplinary approach. Some of the best innovations throughout human history have come from outsiders—people who weren’t experts in the field they ultimately transformed.

This holds true in AgTech as well. Entrepreneurs should surround themselves with non-ag people—those who can learn agriculture but bring fresh perspectives from adjacent industries.

Investors should take the same approach. They should look beyond AgTech and tap into talent from human healthcare, drug discovery, biotech, pharma, and other innovative sectors. Finding and pulling these entrepreneurs into AgTech won’t be easy—especially given the exit challenges we’ve discussed—but that’s where groundbreaking, cross-disciplinary ideas emerge.

Entrepreneurs who think this way—who solve problems across the value chain, who rethink business models, and who bring in outside perspectives—will be the ones who drive the most impactful innovations.

Attracting talent and future casting

RP: You’re making a case for bringing in out-of-Ag VCs and out-of-Ag talent. That raises another big question—what incentives can the industry create to attract that talent and capital?

I ask this question to everyone because I love hearing different perspectives. We’ve talked a lot about innovation—both technical and business model innovation. Sitting here in 2025, if you fast forward 10 years, how do you think farming will change?

If you look into your crystal ball—or whatever artifact you prefer—what does farming look like in 2035?

MB: Several key dynamics will shape AgTech over the next decade. Ten years is long enough for the landscape to look radically different, for new companies to emerge, and for significant funding to flow into the space.

Artificial intelligence will play a major role, but likely in areas beyond direct farmer-facing applications. Instead, AI will accelerate molecular development for new crop protection solutions and traits, as well as improve data visibility across the value chain. AI will drive innovation in agricultural inputs, making them more precise, efficient, and effective.

Supply chain efficiency will also improve significantly. Looking back to 2020 and 2021, major ag corporations faced financial trouble due to inventory mismanagement, primarily caused by a lack of channel visibility.

Even today, the industry is still working through that issue. Ag remains one of the few industries where suppliers lack a clear picture of inventory throughout the distribution network. In the coming years, companies will develop new solutions to enhance transparency and efficiency in the supply chain.

Beyond that, I see two other major shifts. First, biologicals will continue gaining traction. Adoption has been slow, and while the curve will likely remain shallow for a while, it will keep moving upward. Biological solutions are here to stay. Second, labor shortages will become an even greater challenge for growers worldwide, keeping automation and robotics at the forefront of agricultural innovation.

Now, here’s a more provocative thought: Ag touches almost every other industry in some capacity. We need to start thinking bigger about how agriculture interacts with these adjacent sectors, particularly energy and artificial intelligence.

AI model training consumes vast amounts of electricity—far more than current renewable energy sources can support. This demand will likely bring natural gas back online and spur short-term stopgap measures to meet energy needs.

This shift presents an opportunity for agriculture to play a bigger role in carbon offsets and even redefine its purpose beyond food production. Can agriculture produce molecules for fuel? Not just ethanol from corn, but entirely new crops designed to generate hydrocarbons or other energy-related compounds?

With ten years ahead of us, we have enough time to reshape what AgTech truly means. The future of agriculture extends far beyond feeding the population—it could fundamentally transform multiple industries.

RP: You're no longer with FMC. What's next for you?

MB: I’m still working that out. Right now, I have a few irons in the fire and several opportunities in play. What I do know is that I’m driven to build and create—that’s been the constant throughout my entire career, and I want to keep doing it.

I love working with startups, coaching and advising founders, and serving as a thought partner for management teams and boards. I’ve done a lot of that over the years, and I want to continue. I also want to stay engaged internationally. Over the past decade, I’ve traveled the world, learning from different innovation ecosystems, and I want to draw from those experiences to shape what I build next.

More than anything, I want to make a big impact—something much larger than myself. While agriculture will always be a focus, I’m thinking more holistically about climate resilience and planetary health. That broadens my scope beyond ag, but still keeps me deeply connected to it. I also want to influence how capital flows into these critical sectors to drive meaningful innovation.

So while I can’t give a definitive answer just yet, these guiding principles are shaping my next steps—and I’m making steady progress toward them.

Other articles relevant to the conversation

- FMC Ventures’ Mark Brooks on the next 10 years in agtech investment: ‘One of the risks is that we repeat the same mistakes’ by Mark Brooks (AgFunder News, September 2024)

- Why agtech needs new capital models to transcend the caloricene — and investors who can keep up by Mark Brooks (AgFunder News, January 2025)

- Guest article: how to unlock trillion-dollar opportunities in agrifood and climate within our lifetime by Mark Brooks (AgFunder News, March 2025)

- SFTW Article: The retreat of CVC in AgriFood (January 2025)