The "T" shape model for Generative AI

What kind of skill sets do individuals, teams, and organizations need in the era of AI?

Programming Note 1: SFTW will be off next week due to the US Independence Day holiday. I will be back in your Inbox on July 9, 2025.

Programming Note 2: It has been a few months since the launch of the SFTW Plus (paid tier). I would love to get some feedback from you about SFTW, irrespective of whether you are a free or paid subscriber. Would you be willing to spend 20-25 minutes on a video call to answer a few questions? I promise to tell you some dad jokes!

The “T” shaped model for GenAI

When I worked at Alphabet X, the moonshot factory, the company looked for people with “T” shaped skills.

In the context of Alphabet X, the "T-shaped talent" refers to individuals who possess a deep expertise in a specific area (represented by the vertical stroke of the “T”) combined with a broad range of knowledge and skills (represented by the horizontal stroke of the “T”) that allow them to collaborate effectively across different disciplines and backgrounds (the horizontal stroke).

Given many projects would die inside the company, it was important that the people hired to work there had the intellectual and emotional capability to shift to a different problem, if necessary.

“Silos are good”

“Silos” is a heavily used trope in all industries.

Information silos.

Teams don’t share information. The left hand does not know what the right hand is doing. It results in sub-optimal results.

Or information is stored such that it is difficult to access.

Professor Hollis Robbins turned the silo trope on its head and wrote another (!!) fantastic essay. She used the example of grain silos (with some fascinating historical background), to illustrate how going deep in a particular area is very beneficial for academic institutions.

Everything about this view is wrong. In the AI era, the responsibility of researchers and specialists to preserve domain-specific knowledge with integrity, to keep going deep while others go broad, will be more important than ever. The universities that protect disciplinary silos are the ones who will thrive.

Prof. Robbins is writing in the context of academic institutions, but the principles hold true in business as well. In Prof. Robbins’ framing, a silo is the vertical part of the T.

There is significant value in teams, organizations, and companies going deep in their area of expertise (vertical part of the T), as they think about incorporating more AI and GenAI based tools within their business workflows or create brand new workflows.

In a recent white paper from McKinsey, “Seizing the Agentic AI advantage”, talked about how organizations are deploying GenAI based tools along the horizontal part of the “T”.

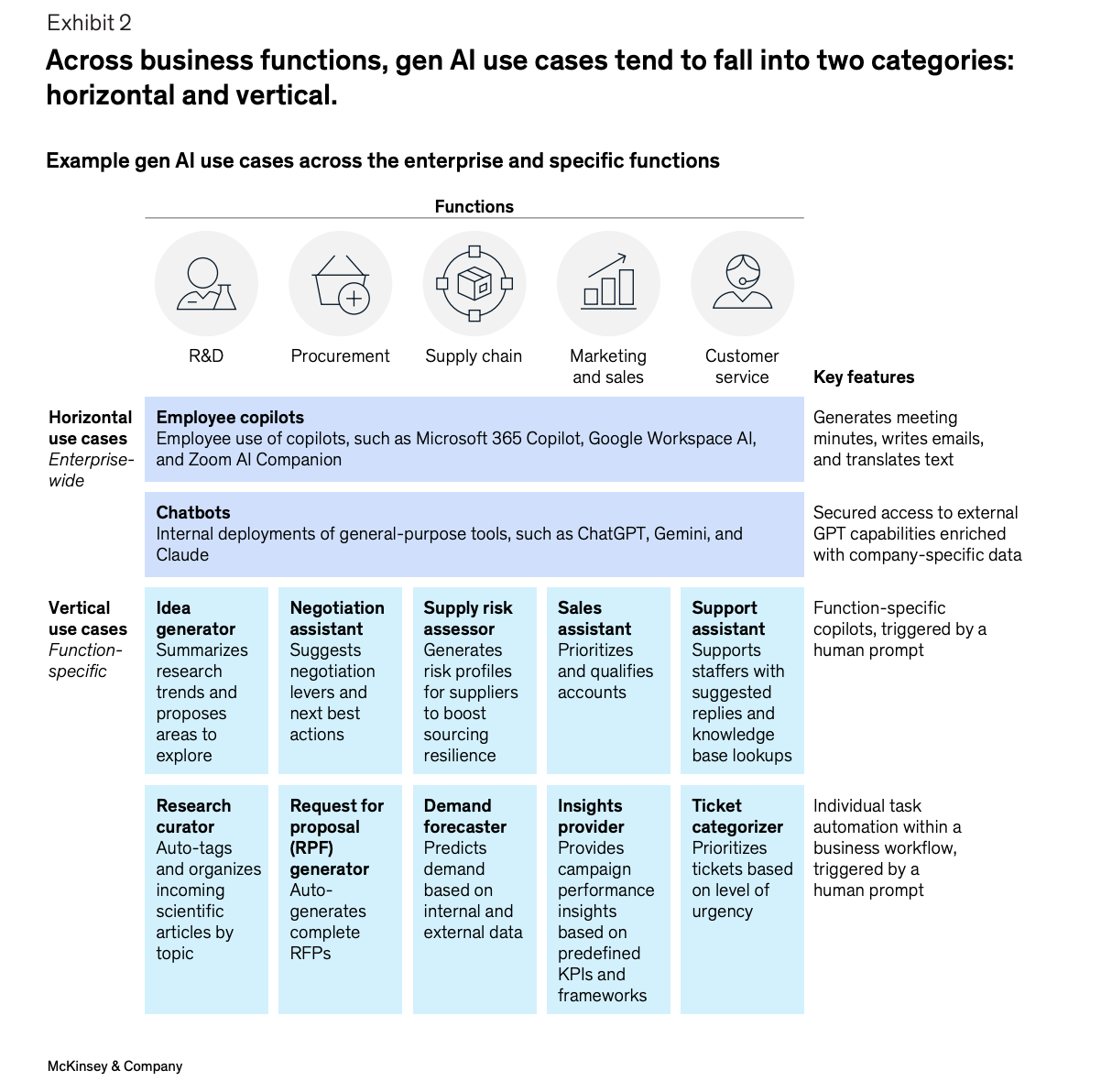

McKinsey categorizes genAI use cases into horizontal and vertical cases. Horizontal use cases are generic in nature. Example use cases are employee copilots, chat bots as general purpose tools.

Many organizations have deployed horizontal use cases, such as enterprise-wide copilots and chatbots; nearly 70 percent of Fortune 500 companies, for example, use Microsoft 365 Copilot. These tools are widely seen as levers to enhance individual productivity by helping employees save time on routine tasks and access and synthesize information more efficiently. But these improvements, while real, tend to be spread thinly across employees. As a result, they are not easily visible in terms of top- or bottom-line results.

Horizontal use cases do not require deep knowledge available to the enterprise. The enterprise does not add a whole lot to enrich the horizontal use case, though the horizontal use case is valuable in terms of higher efficiency for specific functions

Many organizations have focused on horizontal use cases and have struggled to bring vertical use cases to life.

By contrast, vertical use cases—those embedded into specific business functions and processes—have seen limited scaling in most companies despite their higher potential for direct economic impact (see figure above). Fewer than 10% of use cases deployed ever make it past the pilot stage, according to McKinsey research.

Even when they have been fully deployed, these use cases typically have supported only isolated steps of a business process and operated in a reactive mode when prompted by a human, rather than functioning proactively or autonomously.

I did a series of white papers in collaboration with Bayer Crop Science, Digital Green, Kissan AI, and Traive Finance, we actually were able to identify the key reasons for the challenge of taking pilots to production, and provided a blueprint on how an organization could go about doing it. (You can access all the research provided by Metal Dog Labs here.)

(Side rant: In their report, McKinsey talks about unified AI Centers of Excellence, which can prevent issues with fragmented initiatives, and siloed AI teams. According to my experience, a center of excellence is a dumb idea which should be left behind in the 20th century, but McKinsey for whatever reason likes to keep pushing it. Fragmentation and siloed teams (in terms of not sharing information and data) happens due to lack of alignment and incentives which should be driven by top management, not by some ivory tower center of excellence.)

Going back to Prof. Robbins,

The criticism is that you can’t share and collaborate easily with silos. This isn’t true. Disciplinary experts in silos choose all the time to collaborate with those in other silos. Ask them. The Manhattan Project brought people trained in silos together. Then most went back to their silos, with joint appointments in new units. No silos were destroyed

The attack on “silos” usually comes from people outside of a silo, generalists who don’t have deep disciplinary knowledge or focused training. These people don’t want their ideas validated by a community of experts. They find expertise to be inconvenient. The image of the silo as narrow, contained, a kind of ivory tower, seems to support the claim that those in them are narrow, out of touch, or secluded. Someone who has never experienced a famine might easily dismiss grain storage as unnecessarily protective.”

According to Prof Robbins, “silos” are crucial in the AI era. (Just to remind everyone, she is writing this in an academic or research context, but I believe it is true in business as well.) Her use of “silo” is to focus on its depth, and not the way in which the word is used in common parlance. (lack of sharing of information, lack of common incentives, lack of common goals etc.)

Silos are a “bulwark against hallucination.”

Companies have deep knowledge of genetics, agronomy, digital agriculture, inputs, equipment dynamics, grain management, and a host of other topics.

Companies have multiple vertical lines of the “T” which your model providers don’t.

You should go and ask the Bayer Crop Science team, which had to go really deep on understanding crop protection labels, which had very detailed information about the proper way to use a particular crop protection product. It required a very deep understanding of agronomy, economics, crop protection, and the different contexts in which farmers can operate in.

The depth of understanding is critical to build an agronomy co-pilot which provides reliable, trustworthy, context sensitive and timely information to agronomists and crop protection teams.

The depth of data, information and expertise available to teams make the AI breadth most useful. Going back to Prof. Hollis again,

One of the recognized benefits of LLMs is their breadth, drawing connections between disparate fields in ways that might take a human years to uncover. But breadth is shallow and useless without the ongoing digging, complex theoretical modeling, and focus of researchers in disciplinary silos.

Broad LLMs like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Grok provide the horizontal part of the T. You need teams, organizations, and businesses to go deep on the vertical part of the T to provide a solution which is valuable in the context of the business. Broad LLMs do not have the desire or the expertise to go too deep on the vertical part of the T.

On the flip side, if you are a company building a wrapper around an existing GenAI model, without bringing in some unique deep data and insights, or bringing in some other differentiation through your go-to-market or commercial motion, you are ngmi.

You are just coloring the horizontal stroke of the T, to make it look pretty, but you are not adding any new value or any defensible moat to your solution.

Agriculture is a relationship based business. Another aspect of going deep in agriculture is to invest in your customer and partner ecosystem relationships. As we transition from the current on-demand solutions to more pro-active workflows, these last mile relationships and context around them will become even more important to deploy valuable AI based solutions.

As I said in last week’s newsletter,

The good thing is that nobody knows their growers better than people who work with them closely and have trusted relationships. It is the co-op agronomist, it is the equipment dealers, it is the seed salesperson. Every industry, including agriculture has access to this innate knowledge of their customer needs. Even if the agriculture industry will not be developing many of these AI models, they have the know-how, the data, and most importantly the emotional connection and relationships to make these tools much more powerful than just being a chatbot.

So what does this all mean for organizations and investors?

Talent and investment shaping

In the age of AI, you should be looking for more and more T-shaped employees, whether they are engineers, agronomists, customer support or any other role. It might be challenging to have T-shaped employees at the entry level, but you should hire for talent which has the potential to be T-shaped in the future.

An employee’s deep expertise (vertical bar) should be combined with a broad skill set (horizontal bar) which include things like project management, communication, understanding of business principles, and familiarity with areas adjacent to their primary area of expertise. On the broad skill set spectrum, you should look for collaboration and flexibility and the ability to work effectively with cross-functional teams, and someone with an innovative mindset.

You might say, well

Yes though he is not completely right that it is hard to build a multidisciplinary team from disciplinarians. Or rather, it may have challenges but it is better than building a multidisciplinary team from generalists. You need depth always before breadth.

— Hollis Robbins (@anecdotal) June 27, 2025

The same principles at an individual level should be applied at a team or business unit level. Teams and business units should try for T-shaped structures when it comes to capabilities and the investments required to build T-shaped teams and organizations.

This is especially imperative in the era of AI.

This is true for investors as well in the era of AI, where the cost of building a base product (software product, herbicide discovery etc) is going down. Investors should be looking for teams and companies which understand the importance of having a T-shaped team.

For startups and investors, looking for moats and differentiation, the T-shaped structure is a good framework to think about their moats. The moats can come from deep expertise in an industry, deep and extensive relationships, unique insights about your customers etc.

But as Prof. Hollis said,

You need depth always before breadth.

In the era of AI, if you are not one of the big trillion dollar companies, the vertical part of the T is your secret sauce, though you also need the horizontal part of the T to be able to provide products and solutions, which help you build successful careers, and successful companies.

Note: You should check out the dystopian show "Silo" on Apple TV. It has nothing to do with agriculture, but the show and the books are amazing. You can also try "Paradise" on Hulu.