The Vital Signs of Soil: How We Measure Soil Health

Tuesdays with Dr. Tuesday

I am excited to welcome back Dr. Tuesday Simmons for the third "Tuesdays with Dr. Tuesday" monthly issue. Dr. Simmons will be sharing her perspective on the importance of the soil microbiome to agriculture and the development of new technologies over the next few month.

You can read her full bio at the end of this post.

Soil is a living, breathing ecosystem. As such, it can be classified on a spectrum from “healthy” to “unhealthy”, and where it falls has a direct impact on crop growth (1). But how do we measure soil health?

In this article, we’ll dig into why measuring soil health isn’t so simple, the different aspects of soil that we can measure, and how these metrics can be interpreted to improve soil management.

The complexities of soil health

Much like human health, it is difficult to boil down soil health into a single metric. Doctors might evaluate a patient’s overall health based on BMI (body mass index), but there is so much more to our wellbeing than our height and weight ratio.

The Soil Health Institute (SHI) launched the North American Project to Evaluate Soil Health Measurements (NAPESHM) to understand different soil health metrics, and they determined which are most necessary for classifying a soil’s health (2).

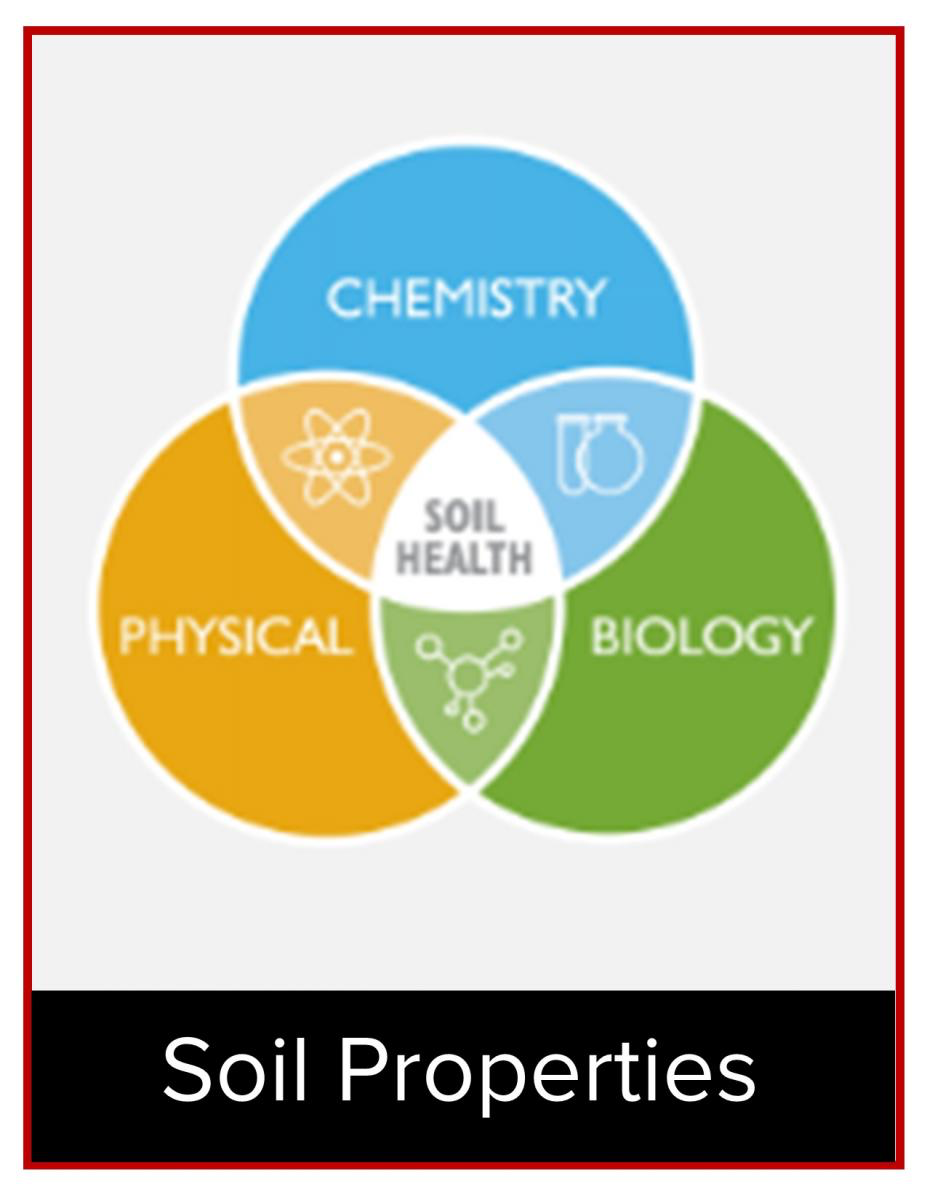

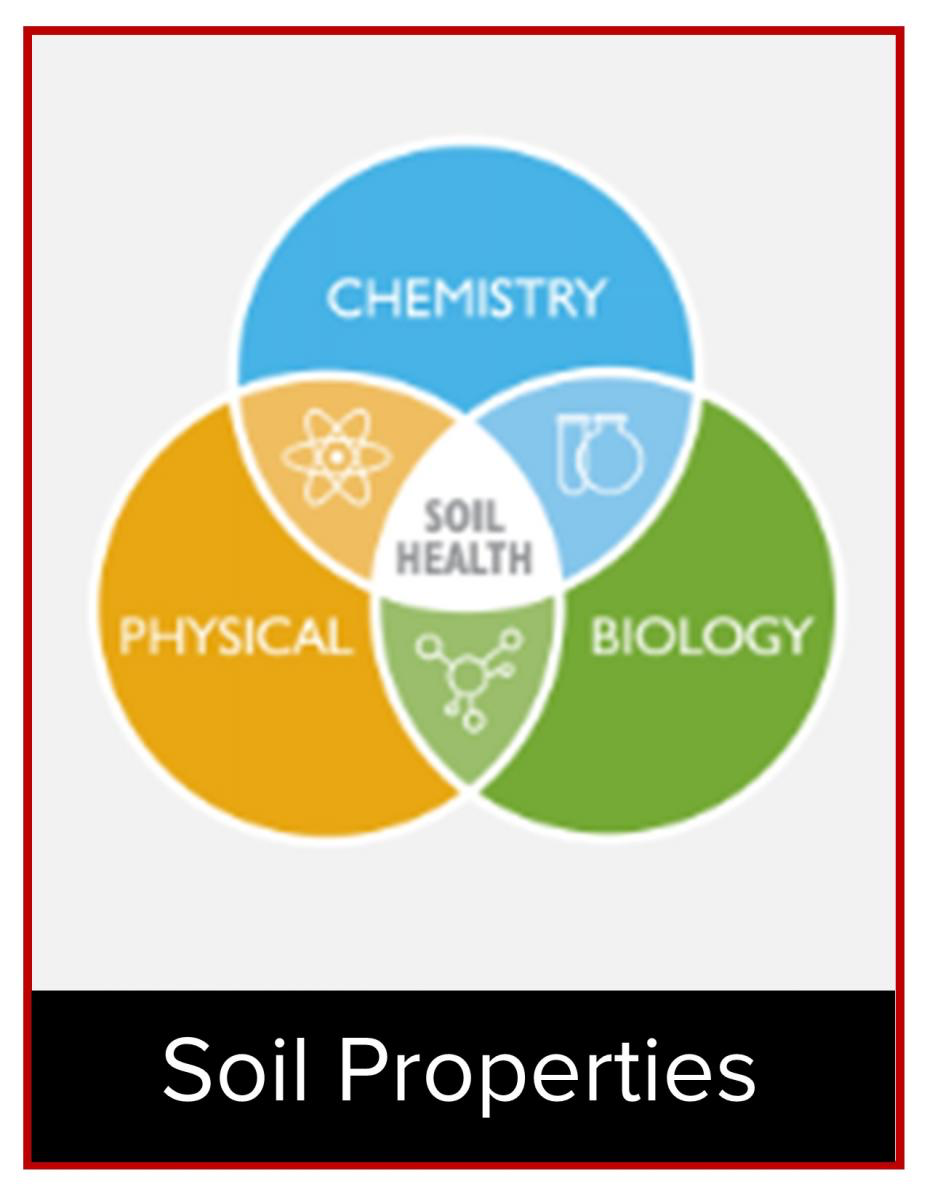

There are many different aspects of soil that we can measure (and I don’t aim to be comprehensive here). These fall into three different categories: physical characteristics, chemical, and biological.

Chemical and physical soil properties

Soil tests became commercially widespread around the mid-1900s, when many farmers were gaining access to chemical fertilizers (4). These “traditional” soil tests measured soil fertility (nutrient content), evaluating levels of macronutrients (N, P, and K). Labs then began to offer measurements for micronutrients, salinity, and pH.

While all important for soil management, none of these individual metrics can provide a good marker of overall soil health.

In addition to standard chemistry tests, many soil labs now offer evaluations of soil carbon (C) and soil structure. Carbon tests include Total Carbon, Total Organic/ Inorganic Carbon (TOC/ TIC), and Active Carbon (aka POXC - Permanganate Oxidizable Carbon).

Organic C levels in the soil are important because this is a food source for the below-ground ecosystem, which includes beneficial insects and microorganisms (see my first post in this series for an intro to the soil microbiome). Organic C was found by the SHI to be one of three metrics that can be used together for the simplest picture of overall soil health (2).

Physical properties that have an impact on crop productivity and can be measured in a lab include: water holding capacity, compaction, bulk density, and aggregate stability. Soil aggregates are soil particles that are stuck together, and their stability is defined by how well they remain stuck together when disturbed by forces such as tilling, water, or wind.

This metric is another found by SHI to be significant to overall soil health (2), and it is related to soil organic matter and biological activity.

The living soil: biological properties

In the past couple of decades, measurements to understand soil biology have become commercially available. These can be sorted into two types of tests: those that identify the types of microbes present and those that measure their impact on the soil.

Who’s there?

If you ask a farmer or agronomist to name a single species they would most like to identify in their soil, they’ll likely name a pathogen. One way to identify microbes in the soil is to do a targeted test (similar to what your doctor might do to see if you have COVID, the flu, or RSV). While incredibly helpful for diagnostics, testing for individual species doesn’t tell us much about the overall health of a system.

One method for evaluating the total microbial community is through PLFA (phospholipid fatty acid) analysis. Different types of microbes contain different molecules in their cell membranes, so evaluating the PLFA in a soil can tell us a lot about the total microbial community (5).

This is a rapid test that can easily report large community changes over time, however it has low resolution (that is, you can’t get a clear picture of individual species present with this method).

As DNA sequencing has become cheaper and more rapidly available, it has become the gold standard for understanding soil microbial communities. DNA can be used to measure biodiversity, which is sometimes used as a measurement of overall soil health (though the SHI does not list it in the three most significant metrics (2)).

High biodiversity can contribute to soil health through increased/ redundant functionality (more types of microbes = more jobs they can do) as well as resistance to pathogens (a diverse community resists the invasion of new microbes).

What are they doing?

While the tests listed above can tell you what microorganisms are present in the soil, they don’t directly measure what those microbes are doing. By measuring the amount of CO2 a soil releases over 24 hours (24h C mineralization potential), we can understand how much microbial activity is occurring.

This is the third metric listed by the SHI in their minimum set of indicators for measuring soil health (2), and the Solvita test is one way to easily measure this. The Haney Soil Health Test (HSHT; aka Haney Test) is another popular, commercially available option that combines macronutrient measurements with microbial activity (6).

It should be noted that although DNA sequencing doesn’t measure activity directly, shotgun metagenomics (sequencing all DNA in the soil) provides a valuable glimpse of the potential activity. By sequencing all genes present, we can search for functions of interest such as: nitrogen and phosphorus cycling, antibiotic production, plant hormone production, and more.

Another note: there are other methods that research scientists use to measure microbial activity, but these are not (yet) available commercially. A major hurdle with these methods is that they require the soil to be flash frozen with liquid nitrogen and immediately placed on dry ice for transport to the lab.

Understanding soil health in practice

I mentioned in the first post of this series that soil is the final frontier. It’s a complex ecological system with so many moving parts that even after decades of study, scientists are just beginning to understand the many different players and interactions happening within the soil. Defining a measurement for “soil health” is an ongoing process that will continue to be refined as we learn more about the soil.

The Soil Health Institute (SHI) recently evaluated over 30 soil health measurements and found that the minimum set of metrics that should be used to accurately evaluate the health of a soil should include: soil organic C, aggregate stability, and 24 hour C mineralization potential (2). Together, these can be used to track how a soil responds to changes in management practices.

Understanding all the available tests and complexity behind soil health can be helpful for farmers and agronomists to make informed decisions about soil management. As the agricultural industry becomes more aware of our impact on soil health, we can leverage the available soil tests to better understand the impact of different farming practices on soil health.

References

- Xing, Y., Wang, X. & Mustafa, A. Exploring the link between soil health and crop productivity. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 289, 117703–117703 (2025).

- Bagnall, D. K. et al. A Minimum Suite of Soil Health Indicators for North America. Soil Security 100084 (2023) doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soisec.2023.100084.

- Soil Health Properties. Osu.edu https://soilhealth.osu.edu/soil-health-assessment/soil-health-properties (2020).

- Birth and evolution of soil testing: What’s next? www.farmprogress.com https://www.farmprogress.com/soil-health/birth-and-evolution-of-soil-testing-what-s-next-.

- Frostegård, Å., Tunlid, A. & Bååth, E. Use and misuse of PLFA measurements in soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 43, 1621–1625 (2011).

- Haney, R. L., Haney, E. B., Smith, D. R., Harmel, R. D. & White, M. J. The soil health tool—Theory and initial broad-scale application. Applied Soil Ecology 125, 162–168 (2018).

Dr. Tuesday Simmons Bio

Dr. Tuesday Simmons earned a PhD in microbiology from the University of California, Berkeley for research into the effects of drought on cereal crop microbiomes. Post-graduate school, she has worked for start-up companies in R&D, sales, and marketing roles with the goal of effectively communicating the value of cutting-edge biotechnology.

As an Application Scientist at Isolation Bio, she worked with leading gut microbiome researchers to improve high-throughput microbial isolation for academic and pharmaceutical purposes. At Root Applied Sciences and Trace Genomics, she has worked to leverage microbiome research for farmers and agronomists. Since 2024, she has worked as a freelance science writer and consultant.

AgTech Alchemy will have its first birthday celebration in Los Altos on September 24, 2025 (Wednesday) at 530 PM. Do not forget to register and bring your sunglasses!