When you need $ 200 million, instead of $ 50 million

What can we learn from the recent shutdown of Guardian Agriculture?

Doing a hardware startup in agriculture is difficult AF.

Earlier this year, Taylor Farms acquired Farmwise after having raised a significant amount of capital (close to $ 65 million).

Two weeks ago, US drone startup Guardian Agriculture shut down after failing to secure the necessary funding. Guardian Agriculture was a manufacturer of autonomous electric drones used for applying crop protection products.

Guardian raised over $ 51.7 million. According to the Guardian, the $50 million was too little capital. They said if they had $ 200 million as a ballpark figure, they could have afforded some of the mistakes. It would have allowed them to invest a lot earlier in areas such as hardware and reliability improvements. (according to Guardian Ag.)

While fundraising was challenging, presenting it as the standalone reason for the shutdown is likely an oversimplification. It's more probable that the difficulty in securing funding was a symptom of deeper, more fundamental issues with the company's business model that investors identified during their due diligence.

Guardian also spent a significant amount of time and money lobbying the federal government to ban Chinese-made drones from companies like DJI and XAG, by calling them “Trojan Horses,” raising national security concerns.

If you dig into some of the details, it presents a cautionary tale of why ag robotics is difficult AF. You don’t need to make it more difficult, as it reduces your chances of success. Innovative technology and some market demand are not always enough to overcome the formidable economic and operational challenges faced by your customers.

Be out over your ski-tips

About 2 years ago (June 2023), fresh off a fundraise, Guardian said it already had $ 100 million in customer orders. They planned to begin commercial operations in support of Wilbur-Ellis in California in the summer of 2023.

In the bankruptcy announcement, they said by June 2025, they had only built eight units of the drone, which does not jibe with the $100 million in customer orders from 2 years ago. The price tag on the drones was in the $120K to $300K range. If we assume an average price of $200K per drone, they were considering customer orders for 500 drones, but they built only 8!

Even as late as June 2025, Guardian said it had a backlog of hundreds of millions of dollars' worth of drones. If you have hundreds of millions of dollars of backlog, it should not be difficult to raise more money. The claim that if they had raised $200 million, they could have continued seems less credible.

It is often enticing to be above your ski tips and view your pipeline as actual firm purchase orders. The $100 million figure was a pipeline number from their sales and BD efforts (my guess). It is essential to separate firm purchase orders with deposits from the letter of intent (LOI) or memorandum of understanding (MOU).

It sends a wrong signal to the market, your current and future team, and changes expectations. If you cannot convert your pipeline to firm orders, you will be in much bigger trouble in the future, as happened with Guardian.

Define your customer and choose the right solution

Despite scanning all the marketing material for Guardian, I am still not clear which customer segment Guardian is targeting. Their 2023 release mentioned that the system is specifically designed for large-scale agriculture. It does not tell you much whether that is commodity row crops or large growing operations in specialty crops.

When it is not clear who your customer is, the rest becomes extremely difficult. Your customer segment has a direct impact on your go-to-market strategy, unit economics, support and operations, product and technology strategy, and who you hire and retain, etc.

The only potential customer they mentioned was Wilbur Ellis in California. It was not for commodity row crops, but specialty crops like vineyards and tree crops. Even though Guardian talked about competing with large corporations like Deere, other drone makers like DJI and XAG, their competition also included startups like Verdant Robotics and others.

It feels like Guardian missed a real opportunity to define a narrow customer segment to commit to and provide a great product and operational experience.

Guardian’s singular focus on electric vertical take-off and landing technology (eVTOL) is a bit of a headscratcher. The total cost of ownership for an eVTOL is higher than that of a typical drone operation.

eVTOL is effective for managing large, contiguous acreage with fewer refill cycles per acre, whether using a service model or a dedicated crew, and it provides safe staging areas for heavier aircraft.

If you need maximum throughput on large, open fields and have access to a reliable provider, heavy eVTOL sprayers can reduce refills and labor per acre. However, the market is young, and vendor durability is still proving out. Heavy eVTOLs create a higher safety bar for operating areas, require crew training, and make logistics and transportation much more challenging. For Guardian, there was a mismatch between their target customer set and the technology's fit for the specialty crop context.

For most farms today, traditional multirotor fleets remain the lowest‑risk, most available path to aerial spraying. It is flexible, modular, and well‑supported, with substantial gains when you tune droplet size, flight height, speed, and gallons-per-acre to the job.

Keep your unit economics and throughput math honest

One of the significant challenges that has plagued AgTech is tall claims that work only in the most ideal and pristine conditions, but fall way short in real-world situations. For example, it is common for AgTech startups to promise significant yield gains based on small experiments conducted in particular contexts. Agriculture is context-dependent, and the mileage varies widely depending on the context.

DJI dominates the agricultural drone market. DJI leverages massive economies of scale and a well-established global supply chain to offer sophisticated and reliable drones at a fraction of the cost of what a US-based competitor could likely achieve.

While Guardian's SC1 was larger and provided different capabilities compared to many of DJI's agricultural models, it still operated within the same ecosystem. Potential investors would have been wary of the immense challenge of competing with a market leader with such a significant cost advantage.

Guardian’s unit economics must have been challenging. Guardian did not help itself by presenting the best-case numbers for their capabilities.

The Guardian’s published numbers for acres/hour assumed the best-case scenario of 2 gallons per acre. The actual acres/hour calculator will be approximately equal to

(Tank capacity)l ÷ Gallons per acre) × (60 ÷ Cycle minutes), where cycle minutes = flight time to empty + battery swap + refill + ferry/turn time.

In reality, their performance was dependent on gallons per acre, which could be as high as 5 or 10 gallons, instead of the best-case scenario of 2 gallons per acre. The top line of 60 acres/hour is possible only at low spray volumes, perfect logistics, and minimal dead time.

According to MIT News, the Guardian quoted that, depending on the farm, the machine(s) could unload 1.5–2 tons/hour.

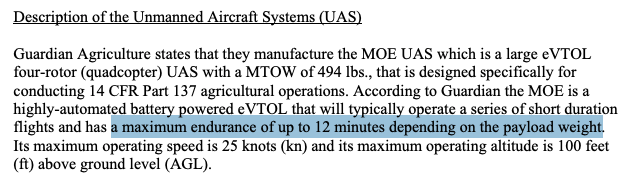

FAA exemption documents for Guardian’s aircraft, however, describe ~12 minutes maximum endurance and a 20‑gal (≈167–200 lb) payload.

Image from FAA Exemption for Guardian (formerly known as Kiwi Technologies)

At 200 lb per sortie, 1.5–2 tons/hour would require 15–20 sorties per hour (60 minutes ÷ 15–20, ≈ 3–4 minutes per flight + refill)

This torrid pace is not realistic for a single aircraft given endurance, turns, refills, and battery swaps.

It’s plausible only as a fleet number or under particular, low-gallons-per-acre, short‑hop conditions, which the marketing doesn’t make explicit.

The acres/hour is also dependent on field type, turn-time components, battery cycle health, drift/nozzle settings vs. label, weather windows, and any need for post-job quality checks.

When you are not clear about your unit economics, it is much harder for your sales team to find the right customer. It is also much harder for a customer to understand how your offering works for their business, and it can provide a positive ROI.

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

Their product only had one buyer who deprioritized tech and drones. It is common to have this when you have your first customer, but it is odd to see this for Guardian after they have been around for almost 8 years.

If you are a new startup in a B2B space with a big, ambitious, and different vision, depending on the strength of your storytelling, you can snag a large customer who buys into your big story. The reality often is that this customer is a set of one, and there are hardly any other organizations with such an approach.

You mistakenly believe that many other potential customers will need products and services similar to those that the one large customer is buying from.

If you are not able to expand beyond this one large customer, it starts a vicious cycle.

Given your survival is beholden to this one customer, every time they ask you to jump, you ask, “How high”?

Another challenge for Guardian was the potential absence of any interim revenue, which could create a safety valve for the company.

In the case of Guardian, Wilbur-Ellis might have withdrawn or lost interest in drone-based spraying. When you lose your only potential customer, and you have raised $ 50 million, there are not a lot of options left on the table.

Stage-gate your R&D plan

Building a large‑payload spray eVTOL (electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing) drone is an industrialization problem, not a gadget launch. It is essential to stage-gate your plan through R&D and start with a small < 10 unit pilot fleet. It gives you and the market confidence that you can do it on a small scale.

It also provides you with an opportunity to test your product in different real-world scenarios, iterate, and advance to the next stage of building a 50-unit regional fleet, ensuring reliability and gross-margin gates between each unit. Given that Guardian had been able to deliver only eight units, the project was in the very early stages of development. They were not ready for a large deployment with a big customer like Wilbur Ellis.

Manufacturing, support, and operations are part of your product

The SC1 was a large and complex piece of machinery. The logistics of transporting, maintaining, and operating a fleet of these drones would have been substantial. The company underestimated the practical challenges and associated costs of deploying their technology in the real world, a factor that would have given potential investors pause.

Guardian's model focused on providing a service rather than just selling drones. While this can create recurring revenue, it also means the company bears the brunt of the operational costs and complexities.

Spray season can be unforgiving. One needs to establish the field service and parts before launching glossy marketing. Given the large size of the SC1 drone, the logistics associated with the drone operations were not trivial. Their product was hard to transport, costly, and required real logistics to use.

This model requires immense capital to build out a fleet and the necessary support network before achieving profitability, a proposition that likely appeared too capital-intensive for many investors in the current climate. It might have been more prudent to solidify their manufacturing operations rather than get distracted by lobbying efforts.

Lobbying can backfire for you and the industry

Guardian spent years lobbying to get some of the lower-cost drones like DJI banned. Even though they didn’t say it explicitly, they raised significant concerns about companies like DJI and XAG, which are Chinese drone companies, by calling them Trojan Horses.

Outwardly, it seems Guardian’s approach was to target their competition, who might be using DJI/XAG drones, which are much cheaper than their own drones. It is strange for a startup to try to be competitive by using legislation as a lever. Large corporations typically play the legislation game to keep the startups away.

Policy advocacy group, Commercial Drone Alliance (CDA), says it takes no position on country‑of‑origin bans. It frames any prohibition decisions as a federal government call, and (if adopted) asks for adequate transition periods so agencies and businesses can shift responsibly.

On the other hand, Guardian spent years inside FAA exemptions. BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line Of Sight) normalization only arrived as a proposed rule in Aug 2025 after a June 6, 2025, executive order told the FAA to hurry.

That timing would not have saved a company that ran out of cash in August. Crop‑spraying can be done under VLOS with Part 137 and waivers, as BVLOS mainly drives labor efficiency and scale.

As a startup, your limited funding should be focused on offense to build a good product that meets customers' needs and can be manufactured, rather than spending money on defense to attack your competition overall and harm the industry you’re operating in.

If Guardian had spent their time and lobbying dollars building up the US drone industry rather than attacking other market entrants, we would be in a vastly different place. Now, a bankrupt company has made it much harder for everyone else in the same industry to build a new business.

Conclusion

As I said in the beginning, agricultural robotics is difficult AF.

Companies don’t need to make it difficult for themselves and the ecosystem by conflating orders with pipelines, murky unit economics and total cost of operations, and poisoning the well through some head-scratching lobbying efforts.