Why did it take so long to find a cure for scurvy?

A historical lesson from the 1700s

This week’s edition is a bit different from our usual format, as it explores a historical story. There are lessons to be learnt for the current times for food and agriculture.

In plain sight

Why did it take so long for the British Navy to mandate lemon juice for scurvy?

An estimated 2 million sailors died due to scurvy between the 16th and 18th centuries, making it deadlier than combat, storms, and shipwrecks combined.

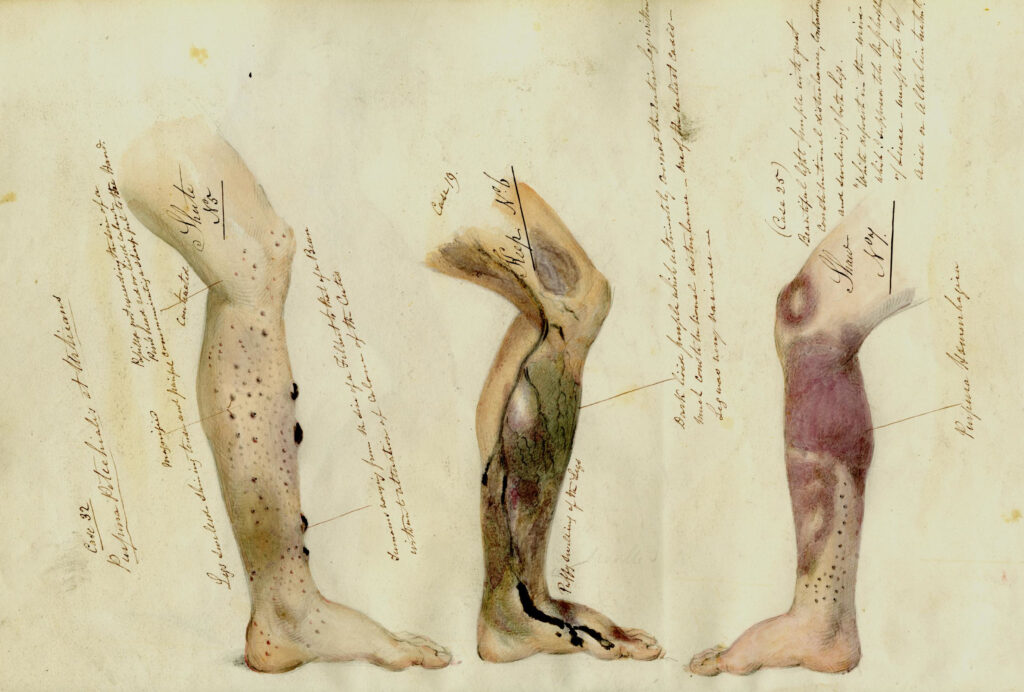

Scurvy is caused by a deficiency of vitamin C, which is essential for collagen production. Without it, sailors developed bleeding gums, joint pain, open sores, and often died. Humans depend on food to sustain an adequate level of ascorbate (roughly 1500 mg in the body of a healthy adult). If it falls below 300 mg, signs of scurvy will appear. Unless the nutritional conditions suitable for living on land could be replicated at sea, sailors on long voyages who consumed preserved food were bound to develop scurvy.

Shipowners and governments normalized the loss of life on any major voyage as the cost of doing business. Most voyages assumed a 50% death rate on long voyages, which required ships to be on the sea for more than 6-8 weeks.

I doubt that there is any common disease today with a 50% fatality rate.

Many theories and hypotheses were proposed about scurvy, and numerous experiments were conducted to identify the causes and potential cures for the disease in the 17th and 18th centuries.

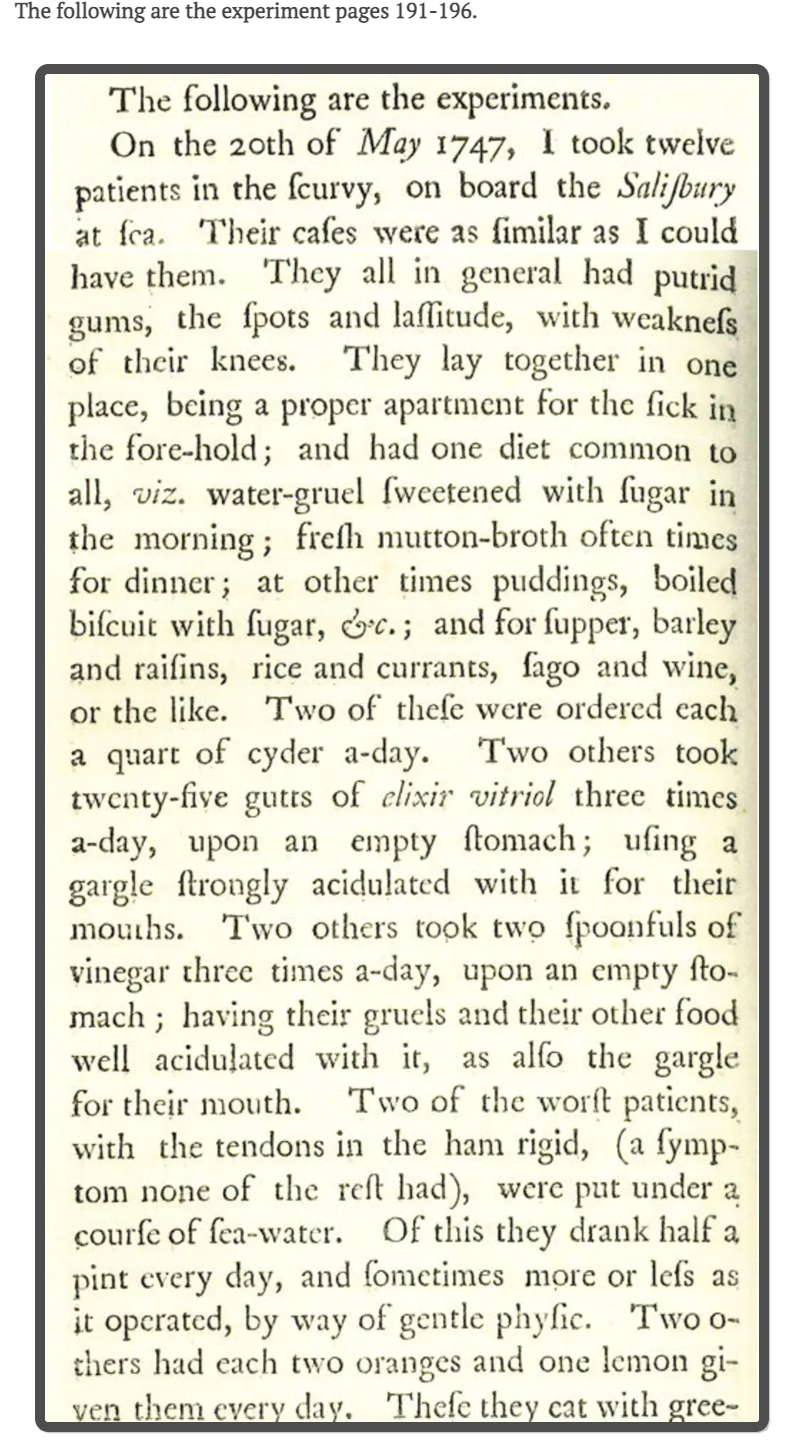

One of the most promising experiments to determine the causes and, primarily, the cure for scurvy was conducted in 1747 by James Lind, a newly appointed surgeon.

Lind’s Experiment

James Lind, a newly appointed surgeon, conducted an experiment in 1747 while aboard the HMS Salisbury.

He took 12 men and separated them into 6 pairs. He moved their hammocks into one contained, damp area and fed them all the same standard diet. He gave the separate pairs the following trials

- 1 quart of cider per day

- 25 drops of elixir of vitriol, 3 times per day

- 2 spoonfuls of vinegar, 3 times per day

- 2 oranges and 1 lemon per day for 6 days (when the ship ran out)

- Three times a day, consume a nutmeg-sized amount of “electuary” (a medicinal paste) made from mustard seed, garlic, dried radish root, balsam of Peru, and gum myrrh.

- The pair with the worst symptoms had the misfortune of being given a half pint of seawater per day.

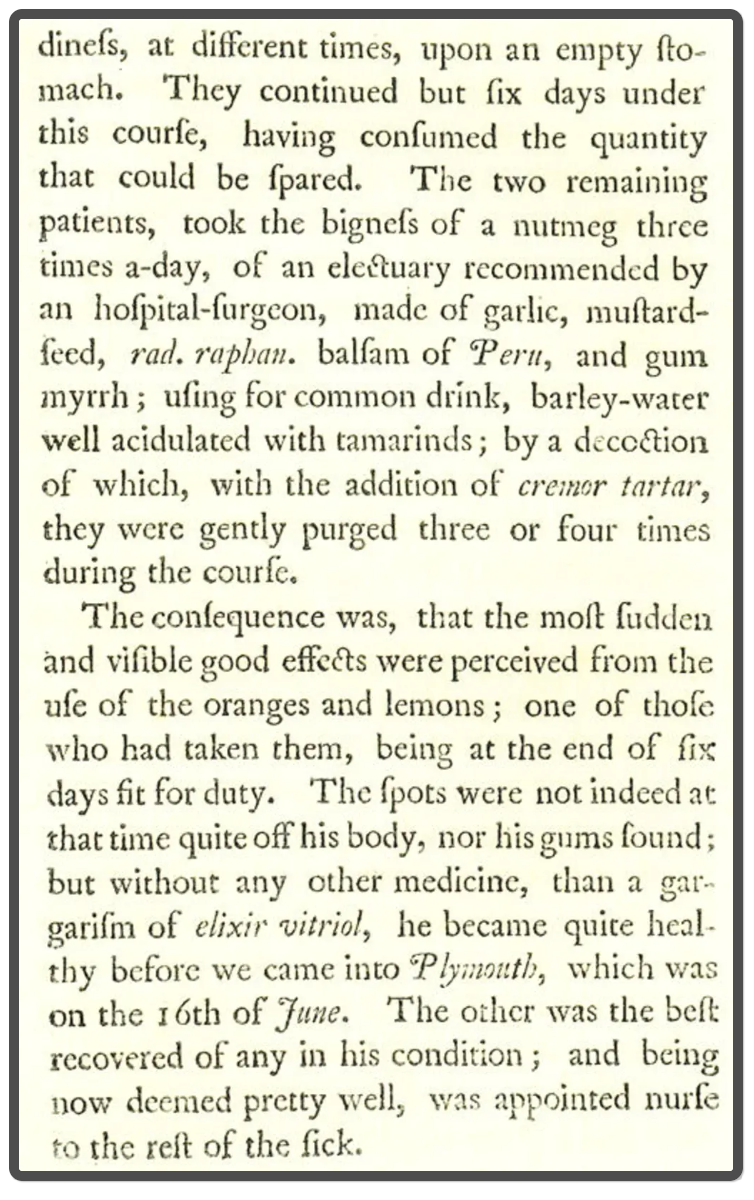

Unsurprisingly, the pair that received citrus fruit recovered quickly. They were then promoted to assist in nursing the rest of the sick men. The men who received the cider also responded well but were still too weak to return to work.

Lind’s work, “Treatise on the Scurvy,” was published in 1753, but it took until 1795 for the Royal Navy to make it mandatory to issue a supply of lemon juice for the sailors.

This was 42 years after Lind’s work was published.

Subsequent voyages demonstrated that a combination of fresh food, hygiene, and ascorbic foods, such as lemon juice and oranges, could help prevent scurvy.

And yet, no matter how many times the connection between scurvy and produce was demonstrated, people kept forgetting it. Cures for scurvy continued to be lost and found, only to be lost again.

Why did it take so long for the British Navy to mandate lemon juice rations?

There were many reasons why thousands of sailors continued to suffer from scurvy on long voyages, even after James Lind’s successful experiments and the publication of his book in 1753.

Most of the reasons were related to either existing dogma, or were cultural (for example, respecting hierarchy, listening to “experts” only, etc.) or economic (for example, cost of non-treatments, wars, difficulty in security supply of lemons, etc.) in nature.

For hundreds of years, the belief (which came from Hippocratic foundations) that all illness stemmed from an imbalance in the four bodily humors: the black bile, the yellow bile, the blood, and the phlegm was very prevalent. Many pamphlets were written, claiming various causes for the “distemper” (disease), such as foul vapors, dampness and cold, inherited disposition, and divine issues, among others.

James Lind operated within the dominant medical paradigm of his time, which held that scurvy was a disease of "putrefaction" of the body's humors, maybe caused by the damp sea air and poor digestion. He theorized that acids could counteract this decay, which is why he included several acidic substances in his trial. The success of citrus seemed to confirm his theory, but he failed to understand why some acids were effective while others were not.

Lind was too obsequious to the existing hierarchy and therefore presented his results in a highly confusing manner. Researchers were expected to write in a difficult-to-understand manner, which made their research difficult to understand.

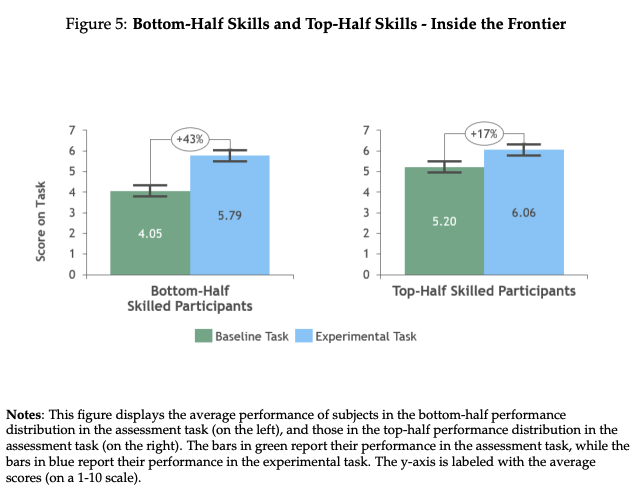

Experiments conducted a few years ago (2012) at the University of Cambridge, which repeated Lind's recommendations, found that fermented liquors contain only trace quantities of Vitamin C and are therefore practically useless for treating scurvy. Although Lind mentioned oranges and lemons, he also suggested other potential treatments that proved ineffective.

Many of the symptoms of scurvy were similar to those of prevailing diseases of the time, such as beriberi and pellagra. This created confusion about the causes and cure of the disease. For example, the leading cause of beriberi is either a diet low in thiamine (Vitamin B1) or a problem that limits the body’s ability to process thiamine. The symptoms of beriberi are very similar to those of scurvy and include nerve degeneration. Degeneration typically begins in the legs and arms and may lead to muscle atrophy and loss of reflexes.

The diet on ships often resulted in Vitamin B1 and B3 deficiencies. Staple foods on ships included hardtack (ship's biscuit), salted and preserved meats, and beer. Thiamin is water-soluble. It is easily leached out of foods that are boiled, and much of the nutritional content is lost when whole grains are processed into ingredients like flour for biscuits.

Pellagra is a nutritional deficiency disease caused by a lack of niacin (vitamin B3). The classic symptoms of pellagra are known as the "four Ds" of dermatitis with skin lesions which appear on the neck, hands, feet, and face, diarrhea accompanied by abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, dementia with confusion, memory loss, and hallucinations, and in severe cases death. It is easy to confuse it with scurvy.

Watercolor illustrations of scurvy symptoms by Henry W. Mahon, a ship surgeon on the Barrosa, a British convict ship, ca. 1841.The National Archives UK

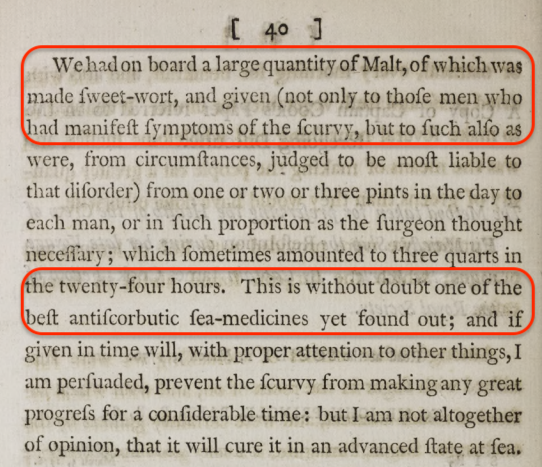

People in authority and significant influence continued to push for non-working solutions. For example, Captain James Cook gave a lecture to the Royal Society on March 7th, 1776. In the lecture, he promoted the efficacy of malt of wort.

Captain James Cook’s lecture to Royal Society, March 7, 1776

James Cook was awarded the Copley Medal in 1776, which is the most prestigious award from the Royal Society of Great Britain.

"For his Paper, giving an account of the method he had taken to preserve the health of the crew of H.M. Ship the Resolution, during her late voyage round the world. Whose communication to the Society was of such importance to the public."

James Cook endorsed wort of malt in a circuitous fashion, but the establishment promoted it as they believed in it. Cook’s treatment plan included cleanliness, fresh vegetables, lemons and oranges, and wort of malt, but the establishment focused on the wort as the real treatment for scurvy. Both the voyages with James Cook didn’t have any deaths due to scurvy, but the real cause of the lack of scurvy was hidden due to Cook’s treatment plan which included lemons and oranges.

Wort of malt was cheap, easy to prepare, and could be stored indefinitely. Famous physicians who were connected with nobility continued to push their own theories on the wort of malt. Given

It kept the issue confusing for many decades. The Royal Navy was loath to change its recommendations or policies due to a lack of a clearly defined treatment option. The Royal Navy wanted irrefutable proof of a specific cure for the dreaded disease before changing its regulations.

Even when captains suspected the properties of lemon juice to prevent and/or cure scurvy, lemons were often difficult to get as they were mostly grown in Spain and the Mediterranean. Frequent wars between England, France, and Spain, reduced the priority of efforts to find a cure for scurvy, as navies were frequently busy fighting naval battles. They also placed a lower value on humans compared to ships, as ships were expensive to build and maintain.

Ultimately, Sir Gilbert Blane, as a Scottish physician and influential medical reformer, was convinced by Lind’s work. He used his position as physician of the fleet to influence the powers to be. He developed a method to preserve lemon juice for long sea voyages by adding alcohol. He demonstrated effectiveness in the West Indies fleet. He wrote a 16 page detailed letter to the Sick and Hurt Board in 1781, which detailed his findings and his methods to take care of the health of sailors.

Finally, the conclusive proof came in 1795 during a 19-week non-stop voyage by HMS Suffolk from England to India. The crew was given daily rations of lemon juice preserved in alcohol, and not a single case of scurvy occurred. The crew arrived in better health than when they departed. This clear and successful demonstration was the final piece of evidence the Admiralty needed to issue definitive guidance for all ships leaving the shores of England.

The end of scurvy on the seas

The advent of steam power increased ship speeds, and better navigation tools like the chronometer reduced the chances of the crew getting lost. Due to this, trips got shorter and shorter in duration for the same distances. This reduced the risk of Vitamin C deficiency kicking in, and the issuance of lemon juice to all sailors for voyages finally brought scurvy under more or less complete control.

Even though the solution to scurvy was in plain sight, it took almost half a century for the Royal Navy to act to protect its own people. The cost of this delay was severe, high, and real.

References

- George Anson’s diary and trip report from the 18th century)

- James Lind's book from 1753, “Treatise on the causes of scurvy”

- James Lind and the cure of scurvy: An Experimental Approach by R. E. Hughes.

- A New Voyage Round the World by Charles Dampier

- Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. Bown, Stephen R. 2003

- Scurvy at The Saint Croix Settlement by National Park Service https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/scurvy-at-saint-croix.htm

- “Scurvy, The Disease of Discovery” by Jonathan Lamb (2017)

- The Age of Scurvy